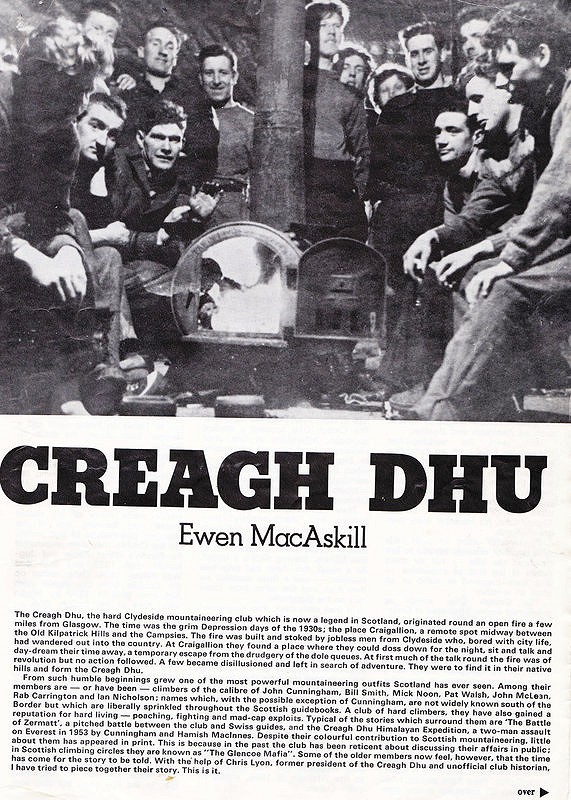

John Cullen was born in 1928 and brought up in Maryhill, Glasgow. A restless child with a penchant for climbing the sandstone walls of his parents' tenement house, John later found himself at the centre of Scotland's notorious Creagh Dhu Club, nicknamed 'the Glencoe Mafia': a group of toughened Glaswegian climbers whose grit was born out of the Great Depression of the 1920s and 30s. Suffering under the heavy burden of unemployment, dole queues and widespread poverty in the city slums, curious young men sought refuge in the contrast of verdant countryside to the north. A one-penny tram ride to Milngavie brought disillusioned minds to the gateway of the Scottish Highlands and offered an escape from urban monotony.

A fiercely exclusive club whose membership often but not exclusively revolved around cutting-edge ability, the group was revered for its calibre of climbing elite. Names such as John Cunningham, Bill Smith, Jimmy Marshall, Chris Lyons and latterly Rab Carrington became well-known through their adventures undertaken whilst in the club. An indefinable recruitment process - with no possibility of application, but invitation - appeared to be based mostly on character traits and a general ability to 'fit in.' The social side played an equally important role alongside climbing endeavours, with an unlikely mix of working and middle class men gathering around campfires and roping up together on uncharted climbs - not to mention their mischievous tendencies.

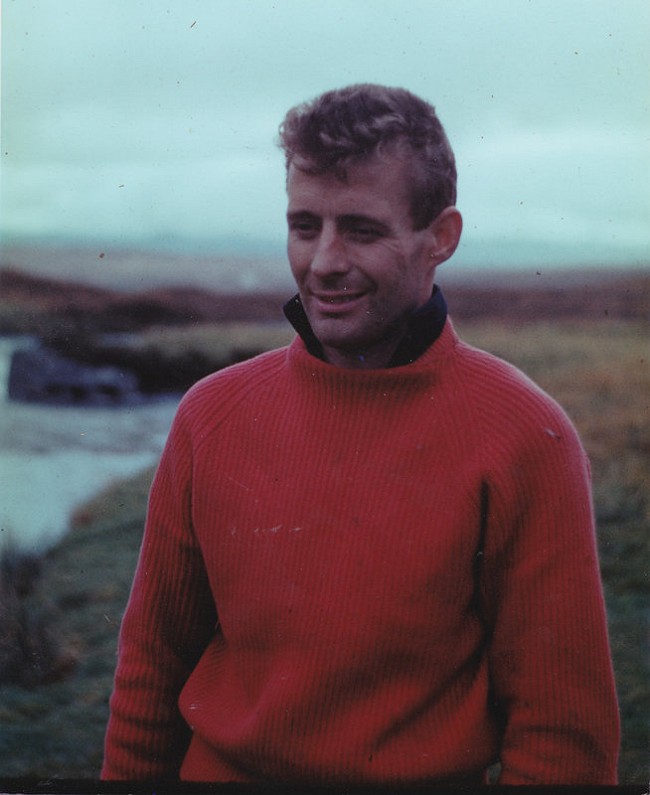

Now approaching 90 and living in Milngavie, John Cullen is perhaps one of the more unlauded characters of the Creagh Dhu. He was a founder member of the Glencoe Mountaineering Club, was instrumental in developing the popular crag just north of Glasgow, The Whangie, has many first ascents to his name and was a successful civil engineer in motorway planning and design. If you've driven around Glasgow, you've most likely driven on a flyover designed by John himself.

My former German teacher, John Ross, got in touch and suggested I meet John Cullen for a chat. He lives just five minutes down the road from my parents' house, and yet I knew nothing of his story. With John Ross' assistance, we met at his house for tea and biscuits, where John regaled us with stories of the Creagh Dhu and his long and interesting life...

'As the editor of Mountain magazine, Ken Wilson, was to say in the case of the Creagh Dhu and the SMC: 'It was almost as if a bunch of East Enders had taken up polo.' Creagh Dhu Climber: The Life and Times of John Cunningham by Jeff Connor

We lived in Oakbank Terrace and at the top there was a retaining wall called 'The Riddie'. It only clicked on me in middle age that because it was red, the name had gone from 'The Reddie' and had been corrupted to 'The Riddie.' There was a gap of 10-15ft then a retaining wall holding the canal and we used to climb on that. My parents were very relaxed about all this, but one thing I started doing was going from the landing window to the toilet window when I was 7. I had to at one point support myself by friction until I could reach round and get the rib. My parents objected to this and stopped me. Another thing I did was run down a 30 degree slope and leap onto the roof of the washhouse, which was insane! I didn't do it regularly, but I did it a few times.

I'll start in 1947 when myself and two lads in the office decided to have a go at climbing. I went to a shop in Gallagate that sold rope, we bought a length of hemp rope and a guide to The Cobbler and we set off that evening. After a long, dry period, conditions were excellent and we spent two days climbing there. I remember I was wearing boots with sole plates and heel plates, which weren't ideal for the job, but we survived. We hadn't sleeping bags with us, we just slept out. Anyway, I was hooked and every weekend after that I went to The Cobbler, sometimes with mates and sometimes even on my own by bus! It was 5 shillings return on the bus to Arrochar at that point, which was exactly my pocket money. That's how I started. The following year, I went regularly to The Cobbler on the same basis and met up with Cunningham and Smith and other people. In 1949 I got a motorbike and Cunningham and Smith had them too. That made a trio! That's when we started doing practice climbing off-season. We went away every weekend and used to go routinely to the Lakes at Easter and spent the summer holidays climbing. The best place we went to was Ben A'an and we used to camp up in the glade and climb on the various routes and solo them; that was the routine. We also went up to the caves at Arrochar and camped and climbed.

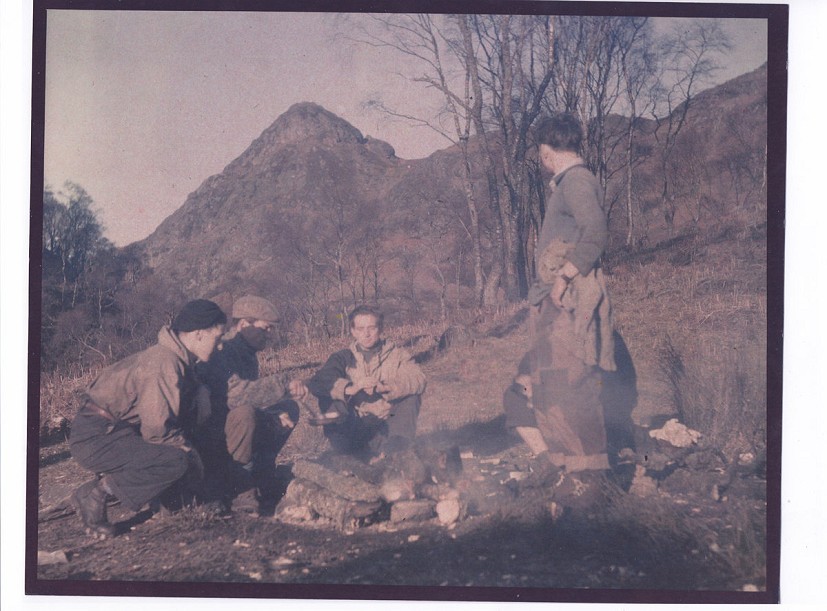

That's Willie Rownie and Hugh Currie who are still my friends. Hugh still holds the European record for the marathon over age 60! That's Bill Smith, that's Charlie Vigano whom I mostly climbed with in that period and that's Cunningham hidden behind Charlie, in front of Ben A'an. That was the sort of core group. Hugh Currie is 93 and still drives every year to the south of France to his cottage.

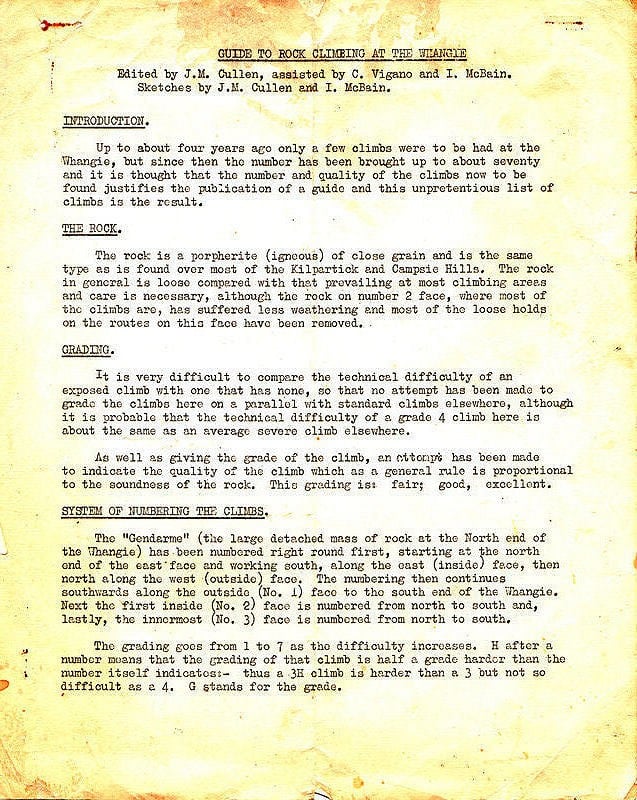

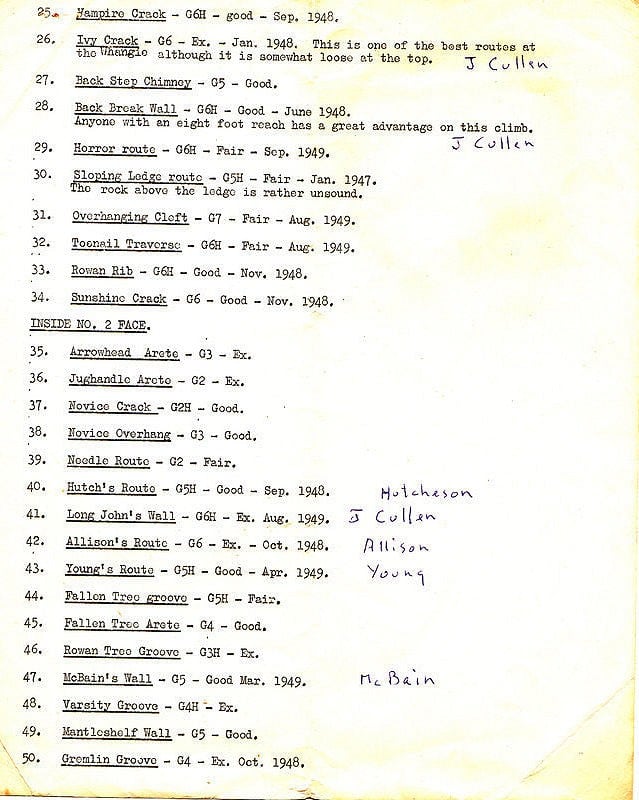

The other place we went to was the Whangie - I was largely instrumental in opening up the Whangie. There were some climbs there but I added a considerable number of good ones. The appealing feature of the Whangie was that you could put in a lot in a day - you just went up and down. You normally climbed down the route you went up.

That's my guide to the Whangie. It sold for the budget price of one shilling and sixpence, of which I got one and thruppence. I was foolish really, I included who did the routes but haven't included any of my own because of my false modesty, which looking back was a bit stupid. It was published in November 1950. I think this was an initial version before it was turned into a newer format. You can keep that, I know which ones I did!

This was the start of it and that was the core group which others gradually coalesced around. We weren't actually in the Creagh Dhu Club at this time, you had to be invited and couldn't apply - we all joined at later times. It was actually later on I think in 1951 when I joined. I was in the Glencoe Mountaineering Club as a founder member and the advantage was that they ran a club bus - it mostly went to Glencoe in summer and winter, sometimes it went to Glen Clova and in the New Year Aviemore, so you could do a few days in the Cairngorms. I was living a parallel life!

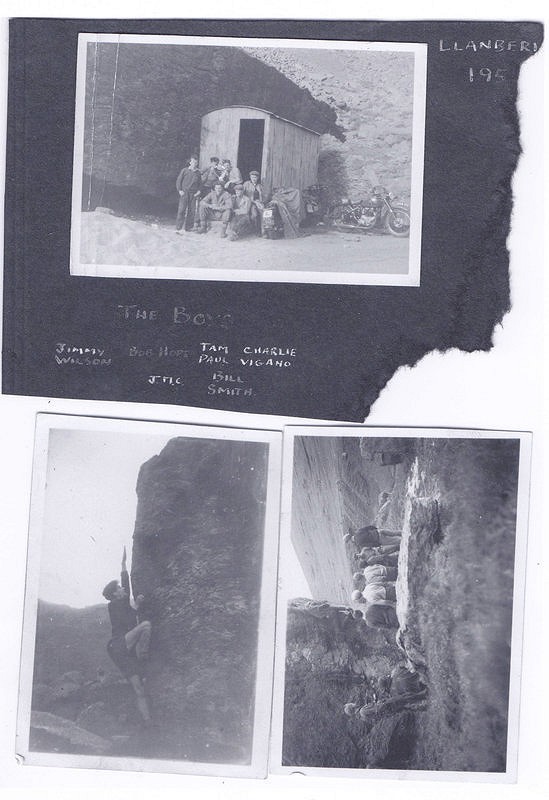

In 1952 the group went down to Llanberis. I remember Brant was mentioned and I didn't know whether that was a sort of basic minimum or anything particularly hard. The first day we were there I led it with Charlie Vigano without any particular bother. I discovered later that none of the others had done it. I'm not trying to be falsely modest, I'm sorry if it comes over that way - I'm just giving it to you straight! Mick Noon had apparently backed off it that summer. Funnily enough you remember some things from years ago and I seem to remember the crux was a v-shaped recess and I think you had to put your foot out and straddle it like a chimney. At that time we never used runners - I certainly never used runners - and sometimes when climbing continuously you were past a crux before you realised it was a crux, and sometimes you'd come to it and the more you fiddled and faddled around the harder it became. I don't know why I found it comparatively easy, but I did.

The photo is of when we did Brant - that's Jimmy Wilson, the real Bob Hope, Tommy Paul inherited from the previous Creagh Dhu as was Bill Smith and Cunningham and there's Charlie Vigano. The photo was taken by Chris Lyon, figurehead and president of the club.

In the late '40s we mostly went to The Cobbler. This is Johnny Cunningham doing the overhanging corner on the boulder at The Cobbler. This is me doing it on the left. Cunningham and I were the only ones to my knowledge who did it routinely. That's Mick Noon, who was one of the early arrivals and that's Hamish who knocked about the club. He was never a member; he was too reckless. That's Charlie Vigano, Willie Rownie and Bill Smith.

In 1948 three of us went to Glen Brittle in the Cuillins and I led the hardest routes there. Crack of Doom, Cioch Direct, Mallory Slab and Groove Route, at that time with hemp rope and nailed boots - well, they were Tricouni nailed boots at that time. In 1947 I bought a pair and nailed them myself, which was quite common then with Tricounis. The first time I used them was at The Whangie and it was foggy, very still. Every twig had half an inch or more of ice particles and it was just like fairyland with the trees below the crag there. We walked up in the mist and at the end of the walk turned the corner and came up out the mist and looked north; there's all the mountains sticking out! We continued up the hill in the brilliant sunshine to The Whangie and had a really good day. I christened my new boots and then walked back down in the mist. It was just one of those magic things that happen, you know!

'It's funny how these interesting events unfold, but it's only if you put yourself in a position to be open for these things to happen, you know. If you sit at home all your life, adventures don't happen to you!'

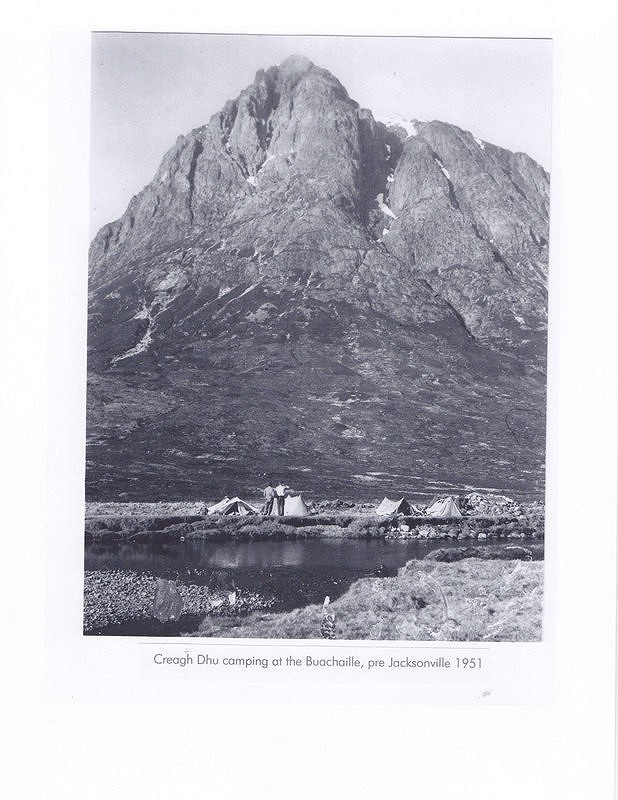

First of all I might say there was a Creagh Dhu Club before the war - call that mark one - who did some limited climbing. Starting during the war and after the war there was mark two, which included Chris Lyon, who was a figurehead and president of the club. Cunningham and Smith had joined in that period and in 1948 by great coincidence I was doing the overhanging corner on the boulder for the first time just as they walked past and went up The Cobbler; I recognised Cunningham. By the end of that year they'd all gone to New Zealand and America and by that time Cunningham and Smith were the only ones who coincided with the mark three period that I'm mainly talking about. The highlight of this was the Buachaille. Motorcycles came in in 1949 and so 1949-52 inclusive the main destination at the weekend was the Buachaille and this was before Jacksonville, so there was a sheep fank with a ground sheet thrown over it, which was a horror story! People generally preferred to camp; that was the stepping stone and a tradition. There was a very lighthearted atmosphere. There was a period when Captain Banks and some of the commandos were climbing and doing training exercises with the Creagh Dhu Club and I missed it, being up north doing surveys.

Cunningham says in his book 'it was always laughter' and that's absolutely true. It was always laughter and there was a period when we went into poems - 'Who are ye in rags and rotten shoes...' - and sang Mostly Irish protest songs. At that time nobody really drank, nobody back then went to the King's House and we didn't go to the bar at Ben A'an. It was just the way it was and Cunningham and Smith really set the tone.

I think I did all the routes on Rannoch Wall. After this main period I did a bit of climbing and I did the route that Smith and Hamish established to the extreme left of Rannoch Wall, a funny name - very well protected actually. [Wappenshaw Wall (VS 4b)], that's the one. I never led - what was that first hard one that Cunningham did on the Buachaille that's dead famous? [Carnivore (E2 5c) ]? I did that years later as a second. Other than Gallow's Route (E2 5b) and Guerdon Grooves (Summer) (HVS 5b) I did all the routes of that time. I did Guerdon's later with Alec Fulton and he led it. It's a sort of balance route really; there's very little in the way of holds. On a balance climb like that with the support of a rope, it's nothing really, but when Cunningham led it he ran out of rope and whoever was second had to untie and let him finish the climb. I think it was 1963 when Alec Fulton led Yam (E1 5b), which was Extremely Severe and I managed to go up second without assistance from the rope.

I established a few new routes but none of them are really of any great significance. It's my one regret in life, I would have liked to put up one or two classic routes, but such is life. I can't complain!

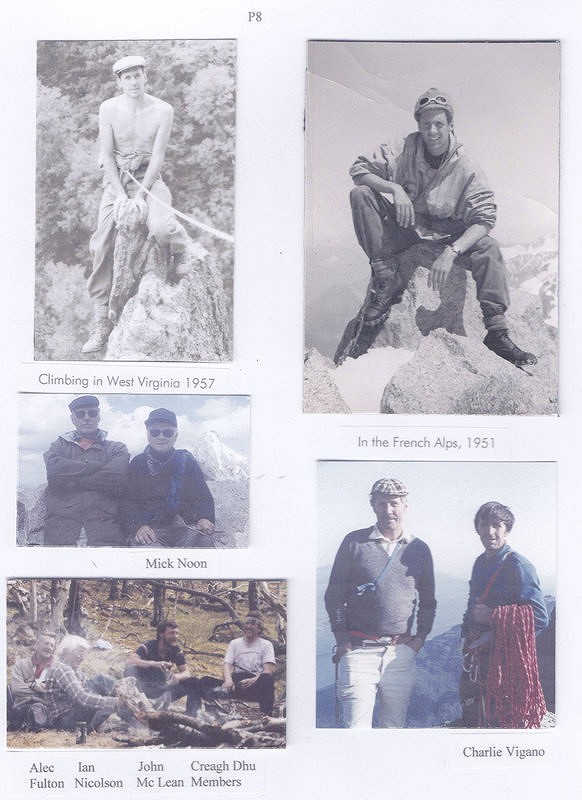

This is a page of my life story which I put together for my children. This is me in Chamonix in 1951, I think. That's me climbing in Pittsburgh - I was a member of their climbing club for nine months. That's me and Mick Noon many years later on one of the Teton peaks and we were just in our ordinary gear. What was funny was we were going up an easy route and on the other side these two heavily armed climbers came up and saw two old pensioners sitting there in the sunshine. This is many years later, too: I'm with Alec Fulton who was a very good climber and Ian Nicholson, another top climber, and Charlie Vigano.

That's just a picture of interest. I think that's Rotten Row. That's when the old slum buildings were being demolished. 1965 thereabouts - mid sixties. That was Glasgow when there was a clear distinction between the good houses and the poorly built ones; there wasn't a gradation. The well preserved ones still exist today, the bad ones have been demolished. I was brought up in a good one with a room, kitchen and a toilet in the stairhead shared with three families. The quality of the finish was better than the house I'm in today. It was a very efficient way of living. Most people had apartments around them so heating costs were low and you could go out to the shops easily. As it happens, the school I went to was not two hundred yards from the house near Possil. We were in the third storey at the end of the street overlooking the canal. One of the interesting sights was the horse drawn barges going past. As a barge would be coming along, a man would leap off it and they'd throw the rope. It was a very happy time, particularly for kids. It was a paradise for kids because the other side of the street used to be a big foundry and that was just like a playground.

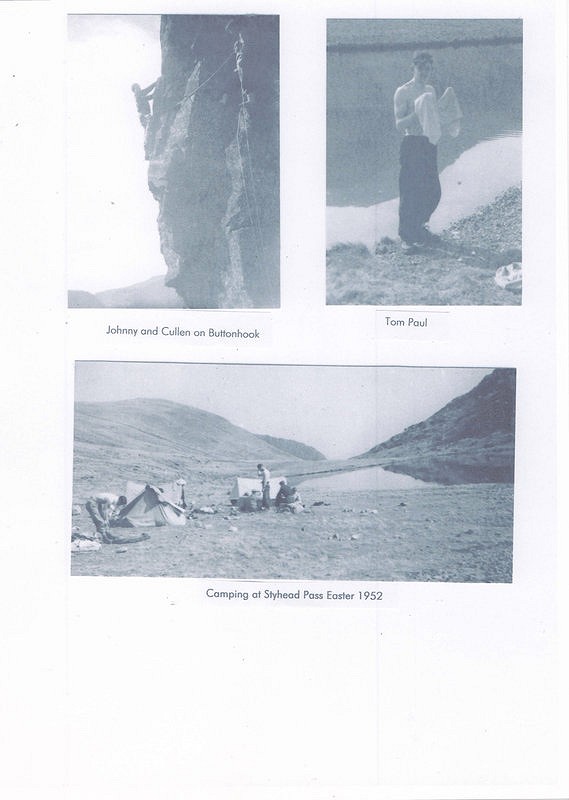

During this period we used to go down to the Lakes every Easter on the motorbikes. That's us camping. That's Timmy Paul and that's me leading Buttonhook with Cunningham. He was a hard man Cunningham. He had also done it before, but where he was belaying from off to the side...the crux is up here...and if I'd come off I'd have come way down to the floor before the rope had come into play. He was a hard character at times.

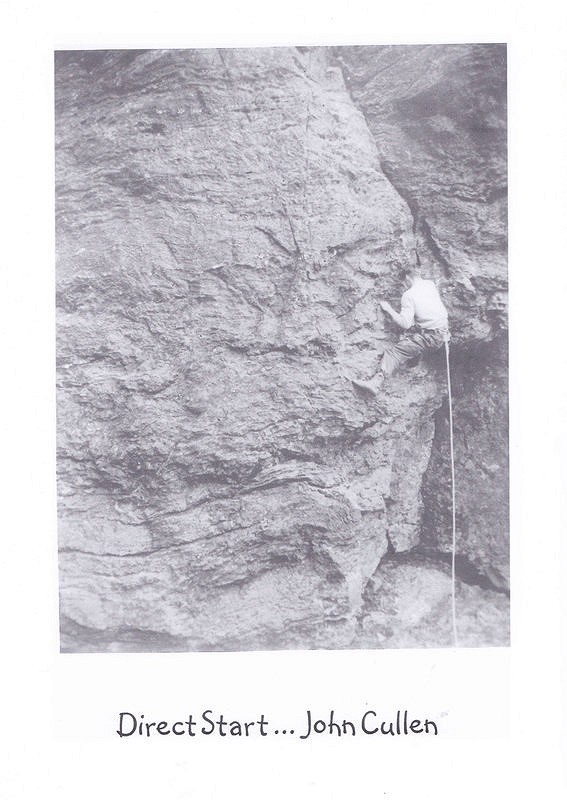

That's me on The Cobbler, the first start to The Catcall. It's not much of a route but this photo shows a lack of runners and I was climbing in sand shoes. It was only for a short period that I climbed in those; before that it was the nail boots and after that it was Vibram boots that I climbed in and found to be OK. I think that was in '48.

That's a story about Creagh Dhu which is interesting. That's me here [points to man in back left corner, peering over shoulders]. That's mostly the old Creagh Dhu or mark two during the war. So what happened in early 1953 was, I got engaged to be married and immediately after was seconded up to Easter Ross in the north east of Scotland. I was there until the end of the year and I used to come down every second weekend to meet up with Ina - my future wife - and every weekend I'd do some climbing in Easter Ross with a local guy. During the course of '53 the old lot disappeared - Pat Walsh and Charlie went down to Manchester, I think Cunningham and Smith were on the Antarctic Survey or something, so the club dissipated briefly. There was this short gap filled with the new generation who had benefited from what we had done; I figure there were 11 in all. Rab Carrington, he went on to found the company Rab and latterly Smith ran the ski system at Aviemore, of which John MacLean was the chief engineer and Currie went on to be a director at the Daily Record. Anyway, that generation did an enormous amount of climbing and a lot of it abroad in the Alps and so on. Finally, at the end of their time there was another generation that came in, whom I met but was not that familiar with.

The outdoors generally was part of the scene and the fires were a really important part of it as well as the bothies. I was instrumental in creating a monument for the Craigallian Fire, I made a bench that still stands there today. I'm not sure to what extent it was related to the Creagh Dhu Club, but the Craigallian Fire certainly played a key part in the development of the outdoor movement, although some people found their way into the Creagh Dhu outside of the fire. This was during the period of mass unemployment when young men made their way out of the city. They would get the tram to Milngavie and walk out maybe 3 miles to Craigallian and certainly in fair weather would sleep out beside the fire.

'The welcoming warmth of this fire attracted hundreds of wandering men. From this developed the Scottish outdoor activities enjoyed today: walking, rambling, scrambling, climbing, skiing, boating and sailing. The group who dominated around this fire were left-wing philosophers who spoke a new language, Dialectical Materialism, Proletariat, the Masses.' - Creagh Dhu Climber: The Life and Times of John Cunningham by Jeff Connor

We took part in all these pranks and stuff. I'll just mention one. Cunningham and MacLean had a sort of thing going on, a competitive spirit or whatever, and at one point I think MacLean had borrowed a big groundsheet off Cunningham, it was actually barrage balloon material; it was excellent, very durable and quite light. MacLean asked him if he could cut a piece off, since it was big enough. So MacLean cuts off a piece in the middle and wraps it up so it's not obvious. I went climbing with Cunningham, got to our destination, opened up the sheet...There was no real malice in it, it was just a bit of fun!

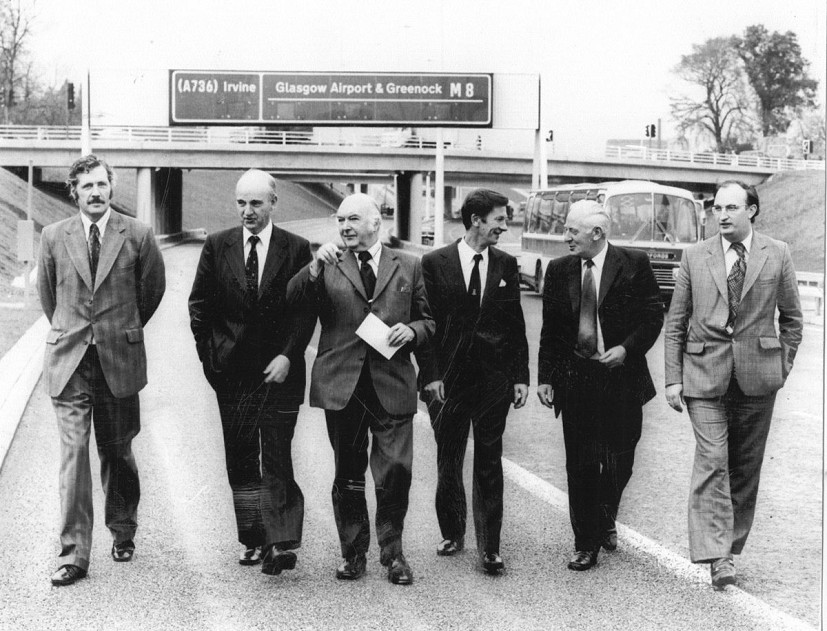

I should mention that at the end of '53 when everybody went away, that's when I got married to Ina. We were very happily married for 57 years and had 4 children. She was a native Gaelic speaker, she came from Lewis. A wonderful person. Professionally I had a good life: one of the things we did early in our marriage was spend 4 years in North America and ended up spending two of those in San Francisco. Our first daughter was born in Hamilton, Ontario and our second daughter was born in San Francisco, where we didn't have any relatives, nor did we know anyone. In San Francisco, just by sheer chance I worked for a company that specialised in freeway design. By an amazing coincidence I got appointed into that group, which was quite specialist even in America, so when we came home I got a job at Cumbernauld New Town where we got a council house that went with the job. Housing was very scarce then in '59, so I got there just in time to design the new road system in Cumbernauld, which were all flyover junctions.

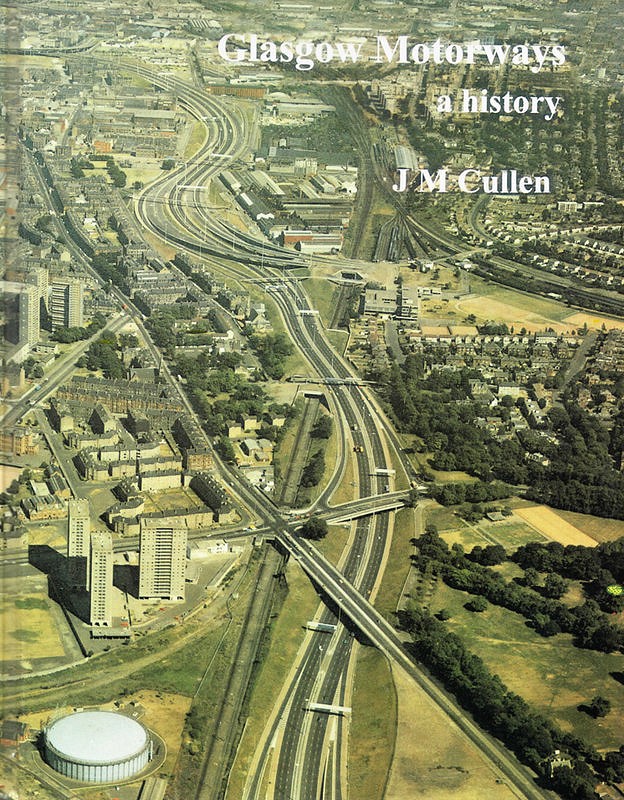

At that time I was more or less certainly the only person in Britain who had designed urban motorways as it was all new over here. Again by sheer luck, when Scott Wilson were appointed to design Glasgow's motorways I joined them right away and again I was the only person who had done it. I'm not claiming sole credit, but I did design the Glasgow motorways and produced a book. I'm not boasting, it was just a very unlikely thing to even end up in San Francisco, as when we first got married we were living just outside Glasgow next to my grandfather's farm in a cottage. I was working quite happily and Ina was teaching at the school nearby and it was a beautiful spot.

It was strange in a way that we decided to emigrate to Canada. I think basically it was too comfortable and we thought well, are we going to spend the rest of our lives here? That was the basic thought and we said no, we'll go to Canada - so we went to Toronto, and then Hamilton, then Pittsburgh and finally two years in San Francisco, which was just like being on holiday as the work I was doing wasn't demanding. So it was a whole series of unlikely events that led to me ending up with this job in San Francisco. If you multiply them up...if someone had said to me the first year we were living at Craigmore, that in three years' time I'd be working in San Francisco, I would say 'How could that happen? There is no conceivable way that that could happen!' We moved back in 1959.

A big part of my life was marriage. Ina was just a wonderful person - she really was. I'm not just looking back with pink spectacles; everyone that knew her loved her. She wasn't into sport in any way at all. On the face of it we had nothing in common, except for the fundamentals of course, but she didn't do anything really; people were her hobby. However, she was very strong and fit. I think she was 58 at the time and we walked the West Highland Way and the Lairig Ghru. One day we did 15 miles and she hadn't done any training for it nor was she into anything active - she was just naturally very fit, healthy and strong.

Later on Hugh Currie and I would go to the Glen Feshie bothy regularly. On this particular occasion, maybe eight years ago, I would have been 83 and Hugh 86...old enough to know better. There was a wooden bridge across the river and then along the other side to the bothy, but at this particular time the bridge had been swept away and not been replaced, so we had to go up the other side. We had stayed in a hotel nearby, set off in the morning and the irony is that we always end up taking back as much grub as we end up taking in, so we thought 'We've had our breakfast here and we're only going to be one night in the bothy - one evening meal, brekkie and we're out - so we'll cut it to the minimum.' It was the 1st of April and a beautiful summer's day. We got to the bothy and in the middle of the night a tremendous blizzard started and although the door was on the catch, it blew it open. It was the fiercest blizzard I'd ever experienced and the whole of the next day it kept going non-stop. The following day it had stopped, but there was about 9 inches of loose snow and it was really hard going, so we had a debate as to whether to wait until inevitable rescue came - which wasn't very palatable - or to make it on our own.

We decided to go for it. Into the river we went; the water was above our ankles and we waded across. The gamekeeper, who lived in a nearby house, saw us and took us in. He told us to take our boots and socks off and gave us genuine gamekeeper's stockings - the real Mackay - and said we could keep them. He gave us coffee, bread and honey, so we asked him if he could run us down to the main road, where there were a couple of hotels we could stay in. He told us his wife had just left him with their two children, so whether this was him doing good to be lucky in life or whatever, I don't know. When I got home I said to Ina, 'Did you not think of raising the alarm?' and I never had a proper answer. She said something like 'You've been a daft old bugger all your life, I just assumed you'd be safe.' It could have been very serious if we'd have fallen in. Apart from anything else, when we were coming in on the first day when it was sunny we had to step in the burn and our feet were sodden. We'd run out of everything in the bothy: fuel, food and paraffin for the stove. It was getting pretty cold. the next day when we went to the car it was -6. It could easily have been fatal. At that time you went out in the winter more or less in what I'm wearing now with a cotton ex-Army anorak or something. It was ridiculous.

'The wild image? Well all I can say is that in the case of the regular club dance we were never invited back to the same place twice in our heyday.' - John Cullen as quoted in Creagh Dhu Climber: The Life and Times of John Cunningham by Jeff Connor

I used to make Gore-Tex bivvy bags. I made trousers from the same material. I wore the same pair for golf for over ten years. It was durable and light. In my later days I did a lot of solo hillwalking and I always carried that bivvy bag and a goose down sleeping bag. In Scotland you cant bivvy because of the midges. In fact, it's pretty difficult to even camp. What I did was start sleeping on the mountain top - no midges! The first time I did it was doing the 5 sisters of Glenshiel. I lay down to sleep; it was fitful but not unpleasant. When it started getting light I saw this figure beside the OS pillar, and if it had been a bit earlier and a bit darker it would have been really eery. It wasn't a very common thing bakc then to bivvy on mountain tops and as it happened, it was this guy's first time too. We did the ridge together and descended onto the road about a mile from the road. On the way back we saw a fisherman selling his catch at the side of the road. I ended up buying two 5lb salmon! It's funny how these interesting events unfold, but it's only if you put yourself in a position to be open for these things to happen, you know. If you sit at home all your life, adventures don't happen to you!

I did one of the first post war ascents of Crowberry Gully, using a long-handled ice axe. For some reason Crowberry had acquired a certain mystique post-war, but it wasn't unduly hard or dangerous. I suppose difficulty varies with the season. The group was made up of me and Charlie Vigano with Rownie and Mick Noon. We'd gone up in the club bus and it was after the time the bus was supposed to have left, so we descended via Laggangarve gully and as we got near the river the group came to look out for us. It's funny and it's a lesson for life, that sometimes things that you think are going to be hard turn out not to be so hard, and things that you think will be easy turn out to be hard. I mentioned that we did these hard routes on Skye and on the way back we did Clachaig Gully.

In 1946, I'd gone on a hiking holiday with John Robertson from work. We had ascended Ben Nevis up the path and I remember seeing these climbers appearing from the north side and thinking they were supermen. I visualised them going up vertical cliffs. Afterwards we did Clachaig Gully; we really 'sqooshed it' as they say. I had an epiphany: suddenly I realised that I was just as good. Previously I had this vision of these people in the world who were fantastic and up there, and you were down here, but I realised 'I'm just as good as these guys!' It was a Damascene moment.

John Cunningham introduced me to wrestling. I don't know if he was interested in it per se or just as an exercise thing. He could always beat me, but one time when he came back from one of his Antarctic trips I beat him. I think John had a soft spot for me, partly because I arrived in the club as a fully fledged climber. When he came back from Antarctica he gave me his Grenfell jacket. He was a strange character. He was a bit hard at times and people would ask him for advice about a particular climb and he would sort of mislead them. Certainly if he was around, there was always a buzz. He was a very lively character and he really was as good as they say he was. He had a perfect athletic body - just absolutely what you would imagine a perfect body for climbing to be.

'There was, in fact, a danger that the Creagh Dhu would become known simply for anti-social behaviour and a few well-embellished, time-honoured myths, until the appearance of John Cunningham and and a group of like-minded young climbers who had set out independently from the city in a search for they knew not what. With horizons made limitless by their penurious backgrounds and the added strength and hardiness of the working-class, they were to change Scottish climbing irrevocably.' - Creagh Dhu Climber: The Life and Times of John Cunningham by Jeff Connor

I should say that Cunningham, Smith and the lads were quite intelligent and well read - conversations were usually quite interesting. I knew Hamish MacInnes very well. I had an epic with Hamish, this would be 1951 or thereabouts, when nobody would climb with Hamish due to his reputation for being reckless. This one New Year he approached Charlie Vigano and me to do the first ascent of Raven's Gully. Looking back it was silly as three on a rope are twice as slow as two on a rope, or take considerably more time, anyway. Time was of the essence as we didn't leave early. Hamish was very good on snow and ice so he led and things went smoothly, but when we got to maybe 100ft or thereabouts of the finish, it became dark and Charlie and I were in this shallow cave. Hamish had led this final pitch and there was a piton halfway up, which he had tied into. By this time it was pretty dark and neither myself nor Charlie could get up this bit. Whether it was psychological or physical - I don't know.

He decided to carry on and solo the climb and finished it except for this 10ft high bit of wall, which you'd normally do by a shoulder, so we were stuck in this little cave. By great good fortune, Charlie and I had just bought these 'moonsuits'; ex-aircrew suits, kapok-filled things. We immediately got into them. It was still a cold night and without them it would have been serious. It was just after 4am when we got rescued - these suits really saved our bacon. We weren't going to bother with a rescue, then Hamish shouted down that he was in difficulties, so then we started flashing the torch. The gully is quite deep so you're only reaching a limited section of road. Again by good fortune, these guys had been socialising at the ski station. They had been told to ignore the light. A party spotted the light and the Creagh Dhu crowd that had been staying came round and up to Raven's and dragged us out. It was our fault. The rope was cutting into the snow, which made it difficult. They brought a rescue stretcher up. We'd gotten past the hard bit as well!

Hamish built a motorbike; he was a very clever guy. One of the clever things he did was come up with the idea of having one book with the best climbs in each area of Scotland. Straightforward enough, but he focused in on that and immediately went to different areas and checked them out for this book, which as far as I know is still in use today. Not only did he have this idea, but he had the focus to see it through. In 1951, I went to Chamonix with a friend, we were walking along the high street and who did we bump into but Hamish - full of bandages. Apparently he had been attempting the first solo traverse of the Charmoz-Grépon. He goes up the Verte and is abseiling down a gap and a sling breaks. The chances of him falling the whole way to the bottom are very high, but who was there to rescue him, but the most famous guide in the world: Armand Charlet. He's there with a party to rescue him close by. Hamish eventually ended up doing a super job with the Glencoe Mountain Rescue Team.

From all the climbing I did as a kid and in the rest of my life, I never got a scratch. On the golf course I got hit directly on the nose, went to hospital and nearly died. I had a great black eye; before they could do the operation to straighten my nose they had to get rid of this and gave me anticoagulants. I was bleeding into my stomach and to cut a long story short, just as Ina was coming in to visit me, I threw out all this blood from my stomach - I was going into shock and had a transfusion. After all those years of hard climbing, I never got a scratch.

When my oldest son was 16, I took him rock climbing. Reasonable stuff: Observatory Ridge on Nevis and up the snow route on Ben Lui - just easy stuff. After my main period of climbing, I climbed on and off to a reasonable standard. My last climb was when I was 60 and my son took me up Ardverikie Wall. It's a classic route, steep with good holds and strenuous. The only reason I was able to do it was that for 12 months previously, I'd been building this house for a client and I had to be there every day, six days a week, so as well as masterminding I was on the mixer, wheeling barrels of cement. When I started I was 14 stone and relatively unfit, but by the end of the two months I was 12 stone. I'd lost all this weight and I was fit because of the exercise and able to get up the route with assistance. It was nice that I finished with my son taking me up it. He has since cycled across America on his own three times.

John Ross interjects:

'This is not a family known for sitting around on its backside!'

To read more about the history of the Creagh Dhu and some of its earlier members, Jeff Connor's Creagh Dhu Climber: The Life and Times of John Cunningham is now available as an e-book on Kindle.

- SKILLS: Top Tips for Learning to Sport Climb Outdoors 22 Apr

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

Comments