Andy Kirkpatrick talks cameras, technology and what he feels gives photographs a meaning so that you can capture those moments of fear, hardship or pure joy whilst in the hills and on the crags.

Before we get into it I need to point out I’m an amateur photographer, and an amateur film-maker and this article does in no way represent the views of someone who knows what he’s talking about. The idea is to take all these things back to basics, as professionals often seem to overcomplicate things, and what they write can only be understood by professionals. This is simply a piece where I examine my own relationship with outdoor photography and my place in it (and it in me).

One problem with capturing people is that more often than not when the camera is produced and a 'camera face' reflects back at the photographer (cheesy grin, thumbs up, scared face etc). The art of trying to really capture the essence of that person in that moment (up to your knees in snow with a huge sack on for example) you need to catch them off guard. Taking a shot without them being aware of it can work, but most people, and pretending to take a photo, then taking the real one a second or two later (when their face relaxes to normal) can work well. By far the best method of all is to take photos without the camera held up to your face (sort of doc style, where you're filming without making it look like you are).

Bringing It Back

First off why do we bother trying to capture the essence of a day on the hill, a holiday to exotic climes, or an expedition to some distant summit? In the past the act of capturing the experience was just the need to document that experience, with no intention to share it beyond your friends and family, perhaps the greatest audience a slide show in a pub, or a shot appearing in a journal or magazine. Now we live in an age where for many everything is public, shots uploaded to Instagram, Facebook and Flickr, every image shared. At one time you might have been lucky to have one picture in a book of the crux of a route like the North face of the Dru, now you can see every pitch, every move, in every season by photo stalking via Google images. Now, I think, what we capture we share without any thought at all. Sure we are all narcissistic and want people to look, but even if they don’t we are just doing what our forefathers did, but instead of pinning butterflies and hiding them away in dusty draws, we upload, upload, and upload, with no real intention of actually doing anything with the images. In the ‘old days’ every shot had a fixed value, the cost of that frame of 35mm film and its processing. Now images have no real value.

I’ve been around the block with climbing photography, big cameras, medium cameras, small cameras, one, two, sometimes three. I’ve stuck them in pockets, in pouches - on my harness, on a strap around my neck. I’ve used print film, slide, black and white and colour (Kodachrome, Velvia and Provia), and my first SD card was only 5 megabytes! The two constants are: a) technology will keep changing, so either spend money to keep up, or work with what you have, and b) whatever system you use, there will be a better one, perhaps even than the one you’re using!

Style

Style is a personal thing. When it comes to photography, for me, the rougher the better. I don’t like views, I don’t like sunsets, I don’t like shots that required someone to get up at 4am and sit on a cold arse all day to get. These things are for parents and calendars (or calendars you buy for your parents). I like raw, I like out of focus, I like things out of kilter, shots half fumbled with one hand on your belay plate (or more often than not, no hands). I like to see a documentary style of photography, images that tell a human story, images your can read once and then look closer and read again. My heroes - Don McCullin, Eric Bouvet and Danfung Dennis (who has mixed stills with DSLR film making).

This picture was taken on the Super Couloir on a ‘near’ Winter ascent (we climbed about 45 or so pitches on the 1700 metre face before getting caught in a terrible storm) and shows Nick Lewis sorting out some rap tat. Making a compelling image from some guy fiddling with some cord may sound tough, but when you’re three days in with zero sleep, and genuinely think you may die, just getting your camera out is a story in itself. This is the number one lesson I’ve learnt in taking climbing pictures, the less you feel able to take a photo the more greater the urgency that you do so.

Like a shot from combat I like it when people don’t focus just on the image, but on the fact that the image was even taken in the first place, asking “Weren’t you scared?”. For me, the more my brain tells me not to take a photo, that ‘this is not the time’, the more I feel compelled to get my camera out.

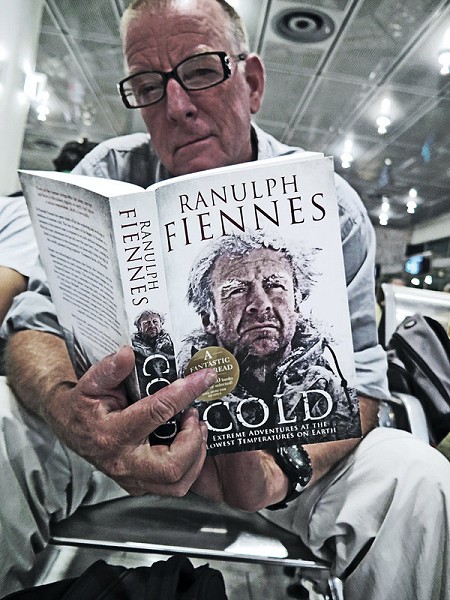

Like combat photography, the climbing photographer must be on top of their gear, and keep it, and themselves safe and in good working order in what can sometimes be very tough conditions. You can draw a lot from combat photographers, both in terms of how to capture images (people, events, details) as well as the day to day process of doing so. Instead of buying a coffee table book or sitting on your arse with a medium format camera, how about getting something like Stacy Pearsall’s Combat photography book (Buy On Amazon Here), full of tips that will work well in the expedition trenches. Also check out books full of the work of these photographers - often there is a clear cross over between climbing and combat.

Capturing the moment is one thing (this really comes down to having a good system in place for being able to get at your camera), but also being aware of when that ‘moment’ may come is probably even more important. If you lead a pitch and come to a crux move you’re handed a great shot on a plate (especially on a traverse), as you know that you’re second will struggle at the exact spot. With modern cameras you can easily shoot several shots at the same time, nailing that exact moment, that expression, body movement, focus that makes a great shot.

Technology

The first camera I ever had was bought from Argos when I was a teenager, and I used it for years, carrying it in a CCS case (back then everyone had CCS cases). I only used cheap print film, meaning I’ve lost most of the photos I had back then, which is a shame. In the end I lost the camera when the tape sewn into the case ripped out and I lost it on a winter ascent of Mitre Ridge (I pointed out this design flaw to Ian Parnell, who carried his two spare lenses in a CCS case on the Lafaille route, but he ignored me, and ended up swapping a grand worth of Nikon lenses for a 1p plastic D ring). After I lost that camera I switched to a series of Olympus mju compacts, being about £100, simple, splash proof and robust. I lost one when it got left on the roof of my car, and dropped a couple, and played around with different pouches and sticking it in pockets on cords. The biggest change was when I began using slide film, which on minimum wage always stung, but being able to sell on photos began, at first, to over costs, before finally pay for the trips themselves. When I started making some money from my photos I upgraded to a series of Ricoh cameras (R and R1) which became the camera to have for a while (used by Andy Cave, Mick Fowler, Paul Ramsden), being very slim, light and with a great lens. So far my photos had been nice, but it was only when I began using an SLR that things really improved.

Climbers like Mark Twight had been using Leica M cameras for a while, and had been getting great shots, but at several thousand quid it was a bit beyond me, so I went with the benchmark climbing SLR the Nikon FM2. I’d met Thomas Ulrich, one of my favourite mountain photographers, in Patagonia in 1999, and saw that he just used the old manual Nikon FM2 - which was very tough (the classic war photographers camera), and light and compact considering what you could do with it. Everything was manual (it had a single watch battery for the light meter, but after a while you could just guess) and I matched it with an old 20mm manual lens, which meant almost everything was in focus. I used this camera on several trips, and loved using it, carrying it in a LowePro pouch on a sling (the camera was compact enough to be used compact style, with the body slid in vertically, not like an SLR, which goes in horizontally). After losing the Nikon hitchhiking in Chamonix (I shudder to think how much money I’ve spent on cameras) I bought a new Nikon FM3a - the last manual camera Nikon made, and a mix between the FM2 and the FE2 (which had auto metering), and used with with a combination of 20mm lens and 45mm pancake lens (this meant the camera was super compact), getting some really great shots with it. The best thing about using a manual camera, something lost in the digital age, was it really helped you understand how to take a photo as everything is manual. I know you can sound like an old fart writing stuff like that, but even a £2000 fully auto fancy pants SLR requires some understanding of shutter and film speed, aperture, focusing and how the image will be exploded (vital when taking photos on snow), things that really helped me fine tune my photography.

I love to try and fill in the picture, and capture what it is that I see in that moment, not a finally composed shot of a grinning partner, but one where things are happening, rushed, not comforting to the norms of good photography, feet in view, and ideally blurred. Again this photo asks the viewer to take a moment to look and figure out what is going on here (notice haul bag hanging far below).

And then I went digital.

I found the switch from analog to digital a bit of a sad one, as in a way I kind of fell out of love with photography, and things just got a bit sterile. Instead of understanding my camera, and learning to to get the best out of it, it just seemed to be a process of buying a new one every year and just sticking what had been state of the art in a draw. The focus on how many pixels and how big a SD card you had seemed to become the main focus, and how good you were on Photoshop meant more than how good you were at taking pictures (funny to think that the slide in your hands had actually been on the mountain with you!).

But times change, and cameras got better, and good ones got cheaper, and I started to get good shots with cameras such as the Cannon G series (latest one being the G18 I think). Waterproof cameras became more common, which when using high capacity cards and good quality batteries could be a real boon on tough climbs, just stuffed in pockets and forgotten about. As for the pictures, they were nice enough, but seemed to lack that artisan quality of film for me.

But then something changed. At one time you had to carry a video camera and stills camera, and sometimes an SLR (when Ian Parnell climbed Everest, he set off to the top with 3 cameras), but all of a sudden you could take little low quality movies with your camera. Things started to get interesting again. Creative juices started to flow. The quality improved. HD film was possible. Now you could not only take shots of your climb, but also film your mates or film yourself, and really begin to document what you were doing, all in a tiny package. With tough cameras you could just whip it out and get a photo, do some filming - even with a blizzard, or in an spindrift avalanche - and whip it back in again. Amazing!

Personally I tend never take landscape photos without a person in there to give it some context, and tend to find such shots a bit dull. Maybe I like stories, and no mountain really has a story to tell (but many to give), while a pin prick of a climber, or some dash of colour on the rock always asks the viewer to imagine themselves there.

Soon the GoPro also appeared - a bit of a gimmick at first, it’s functions and capabilities increased rapidly enough for people - even proper film makers - to take it seriously. This little hunk of plastic, looking like a toy, changed adventure film making. Sure there was a dearth of drivel, people with no imagination or grasp of ‘story’ just filming stuff even they probably found boring, but like all tools, those with skill and ideas took them up and they created art.

As for me I started to carry one small compact camera (Waterproof Panasonic Lumix FT2), and one medium compact (Cannon G18) and a GoPro, plus a medium Gorilla pod tripod. With this kit, which probably weighed less then my old SLR, I could take great shots, capture events ‘combat’ style, get great video and still be able to climb.

Another great leap has been the mobile phone, primarily the iPhone, but also phones like the Samsung Galaxy S5 Sport, which have transformed the nature of documenting events (check out Ray Wood's photos). When asking the cameraman Ben Pritchard what camera he uses when not filming for TV he just replied “my iphone”, finding the quality good enough for anything he wanted to use it for (stills, print, video). If you combine a top end phone with a good case (Lifeproof Nuud Case is probably the best for iPhone at the moment), you can dispense with a camera all together, plus you can also post your pics real time (well, if you have 3G). The main drawback of the iPhone over a Samsung phone is that you can’t carry a spare battery (which you can with the Samsung), plus the Samsung allows the use of micro SD cards, allowing you take take movies with you on trips, or back up images.

Climbing takes places on a broad canvas, very often an epic one, and so we tend to want to capture the experience in the same way, which invariably we fail to do. Instead try and set your nose to the stone, get in close, look for the detail, the needles in the haystack of the day. This little details (bloody fingertips, the stem of a broken wire, the damaged fibres of a rope) can often tell the viewer more about that day than any landscape.

All of a sudden documenting the experiences I have in the outdoors no longer feels sterile, but exciting, challenging and creative. I watch what other people are doing on Youtube and Vimeo and I want to go out and have the same adventures - and film them as well. Technology, instead of making me feel like I’m getting old, makes me feel as creative as I did taking those first photos with my Argos camera.

Rules - but no thirds

This is the bit of the article where I hope you can draw some good from my own reflections on photography.

- Get a system where your camera is always at hand, so there is never any excuse for not taking that shot. This is vital. It doesn't matter how good you are at taking photos, or how ace your camera it is if it stays switched off. I have a piece of bungee cord that runs from a camera pouch (attached with a screwgate, and backed up in case the webbing fails) to the camera, meaning I can leave the case open without worrying about it falling out.

- If you can, get a pouch with a flap, not a zip, as zips break and are impossible when you’ve got mitts on.

- Leave the DSLR’s to the pros. They weigh and cost too much to take on a route unless The North Face is paying you, and their bulk and complexity reduces the likelihood of you getting it out when you need it.

- I would always go for a fixed lens compact, and if your camera has a zoom them make sure you turn off digital zoom, as the quality is never great (remember the more you zoom the more camera shake becomes a problem).

- If you have a GoPro use it as much as you can for fun, and learn how all it’s functions work (especially wide, narrow and standard format). Remember that you don’t have to use it GoPro style (i.e stuck on your head etc), but just like a normal camera (attached a loop of cord to it). If it’s not wet then always use the open back box, as the sound is much better.

- Get a camera that has some form of stabilisation (SteadyShot etc) as this really makes a big difference to image quality, especially for video.

- Carry a small Gorilla pod tripod. With this you can get some great shots, both your normal boring landscapes, but also selfies (attached cord to one leg so you can clip it off to belays) and group timed shots. You can also hold your camera with it, like a handle - steady shot style - when moving and filming.

- In low light conditions turn off the flash and use your head torch to ‘paint’ the scene.

- Buy a second hand FM2 or FE2 off ebay with a dirt cheap 50mm lens and some old film (Ilford B&W or slide) and see how you get on.

- Always back up your card as soon as you can, and store your image in multiple places, ideally not hard drives as these invariably break or stop working. Instead use Flickr (upload images at full res), as you can store up to 1TB of images and video for free (but get a pro account anyway). Also upload to Instagram and Facebook.

- Never delete images in camera. The screen is too small to judge what’s in the shot, and by cropping a crappy image you may end up with a masterpiece.

- In fact never delete any images, or at least leave it a year or two until you do. Often those crappy images tell more of the story than you think, and once trashed they’re lost.

The future

For climbers I think the future looks great, as memory and battery capacity increases (I have a 135gig card at the moment, enough for a few years worth of trips!) we will see a point where we don’t need to think about spare batteries or cards. The transmitting of images will also get better, so we laugh at the very idea of taking cards out (or even having cards), with every shot we take going straight to the cloud (or Instagram, Flickr, Twitter), allowing people to post their experiences real time (something Shackleton and all explorers and climbers of old would have loved). We will be able to film ourselves and post real time climbing up to Death Bivouac, and then edit the movie and post it from the bivy. The idea of non waterproof cameras will also be a thing of the past, as waterproofing via chemical application to hardware becomes the norm, with robustness meaning the days of pouches may be over, in fact the very idea of a box that is held may become a thing of the past, with cameras being worn all over your body.

But don’t worry - no technology will ever remove the ubiquitous bum shot.

- Take photos and video all the time - when you’re too old to climb you’ll enjoy looking back at when you could.

Andy Kirkpatrick, Hull's second best climber (after John Redhead), has climbed El Cap twenty five times, including one day ascents, several push ascents (climbing from the bottom to the top with bivy gear) and three solos. He is currently writing 'Me, Myself & I' and a manual for big wall soloing.

- ARTICLE: Andy Kirkpatrick on Alpine Style Cooking 9 Dec, 2015

- 10 Tips on Staying Warm in Winter by Andy Kirkpatrick 15 Dec, 2014

- The Nose: How to Climb El Cap's Most Famous Route 21 Jul, 2014

- 10 Tips for Climbing El Cap by Andy Kirkpatrick 25 Jul, 2013

- GUEST EDITORIAL: Everest - Sucking on the barrel 3 Jun, 2012

- REVIEW: Fiva - An Adventure That Went Wrong 24 Apr, 2012

- Andy Kirkpatrick - Exclusive excerpt from Cold Wars 16 Sep, 2011

- Making The Jump From Scottish III and IV to V and VI 30 Dec, 2010

- How To Hone Your Alpine Psyche 27 Nov, 2009

- Doctor Gear IV: Best Glove system? 8 Mar, 2009

Comments