Andy McVittie looks at the importance of core from the perspective of coaching and training. He examines what it is, the different types of movement the core is involved in, how that relates to climbing and how we can then train it specifically to improve our climbing.

To be a bit flippant, all muscles in the body are connected, so the core doesn't have a beginning and an end, it's everything. This doesn't mean they are all connected physically. I am not disappearing down the fascia rabbit hole. But they all work together.

You may have heard of muscle slings and the posterior chain etc. This is a bit reductionist, but not a bad working description. When you deadlift you are certainly working the posterior muscles that work together (the posterior chain) hard. But I can't think of a muscle that isn't working hard in a heavy deadlift.

It's the same with climbing. When we try hard to stop a barn door some bits are working harder than others, but everything is working together. No muscle works in isolation, in all sorts of ways. We use tension and control from our fingers to our toes.

If you've ever had to do a head pop in a starfish position, to try and generate some momentum from somewhere, as everything is so tensioned, you know what I mean...

How do we use the core in climbing?

We can hold a static position for minutes whilst resting, placing gear, planning, or just trying to calm ourselves down. We can also wind up our bodies and explode as fast and powerfully as we can. In climbing, we can flip from one extreme to the other in a split second.

We use our core to tension our limbs and body to keep us into the rock, to maintain contact and allow forces to transfer from one end of the body to another during movement.

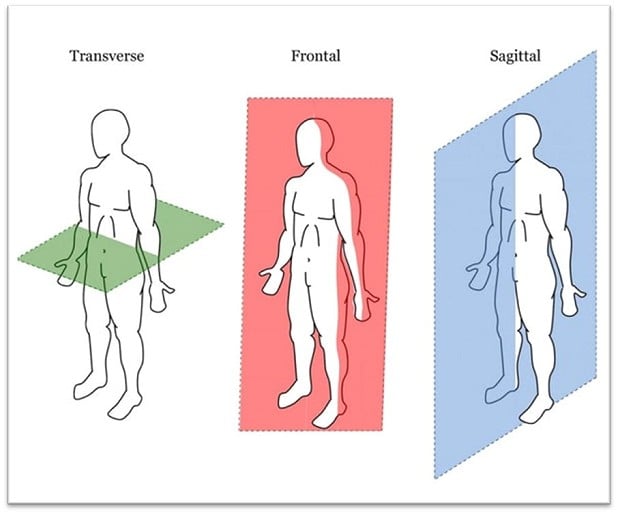

When climbing we move in a 3D nature through all planes of motion:

Sagittal Plane: The sagittal plane divides the body into right and left sides. Movements in the sagittal plane are flexion and extension, meaning forward and backwards. Exercise example: L-sit. Climbing example: bringing your foot up to a hold.

Frontal Plane: The frontal plane divides the body into front and backsides. Movements in the frontal plane are abduction and adduction. Any lateral (side) movement. Exercise example: Sideways dumbbell raise. Climbing example: Using a gaston or side pull, rock overs.

Transverse Plane: The transverse plane divides the body into top and bottom halves. Movements in the transverse plane are rotational, both internal and external rotation. Exercise example: plank with reach through. Climbing example: Drop knee, step-through, flagging, cross-throughs.

In all of these examples, think about what happens once you've moved your limb through the air and made contact with the hold and engaged on it.

You reach your foot up in the sagittal plane onto a foothold (flexion) but when you apply pressure to it and use it to progress upwards it becomes extension. It is the flexion we train a lot (l sits, crunches etc) but it is the extension we need the strength for. This applies to all 3 planes.

Again this is a simplification and when we perform a climbing move it will involve all aspects to differing degrees in both aspects of the movement e.g. rotation and anti-rotation.

In climbing, we use a lot of anti-rotation. Trying to resist an outside force (gravity) that is attempting to pull you out of position. Think of the feeling when you're trying to stop yourself peeling sideways off the wall (a barn door).

Technique

A saggy bum on steep ground can be a sign of being unable to maintain body tension in that position, or it could be a lack of awareness of what you are supposed to do in that situation.

This is a complex mix of knowledge, awareness, skill acquisition and the ability to apply them under pressure.

Your core may be fine, you may just not be using it well by pulling with your toes, keeping hips into the wall etc. It's an entirely separate subject, but if you are not able to access the physical abilities you currently have there's no point making more of them.

So always look at technique first, second and third. The on the wall exercises can be useful for working technique as well as improving the core.

Specificity

This can mean different things to different people in the exercise world. Some use it to mean an exercise that has a direct impact on your ability to do a specific task, such as isolating a pulling muscle to improve pulling performance. Some use it to mean an exercise that tries to copy the task, like pull-ups or lock-offs. Some use it to mean using the task to train the desired variable. So using climbing to get better at climbing.

All have their place. We train finger strength in specific positions, and on specific edges, to get better at holding on. But it is only through climbing that we learn how to apply that increase across the infinite positions climbing puts us in and moves us through.

There is a simple rule to apply here. If you want to get better at steep climbing improve your core for that by spending the majority of your climbing time in structured, steep, climbing sessions.

If you want to improve your slab climbing spend the majority of your climbing time on slabs.

If you are methodical, thoughtful and reflective in what you do you will improve at that style of climbing technically and physically.

On the wall

These can be used as part of a warm-up or done after a climbing session to finish the core off intensely. You can keep the timings the same for either purpose, just alter the difficulty of the movements.

Slow climbing

This is great to use as part of your warm-up. However, it is quite strenuous so don't do this first.

It can also help you identify weaknesses in your climbing movement and core. There's nowhere to hide.

- Simply climb as slowly as you can between the moves.

- It should be at a level that feels challenging but you should succeed – this is not an exercise to failure.

- Use the slowed down aspect of this to increase your body awareness.

- Note if you're pulling and pushing with your hands or your feet predominantly and if that is appropriate for the terrain you're on.

- Breathe throughout – if you're holding your breath this isn't wrong. Just note what you are doing, consider it, and experiment.

- Find the movements where you need to use momentum to get through them.

- Momentum is an essential part of climbing, again just note what you're doing, consider it and experiment. Try the moves again at normal speed.

3-second hover or pause

- This does what is says on the tin. Either hit the target hold and hold that exact position for 3 seconds or

- Move to the target hold and hover your hand above it for 3 seconds

- What are you using to hold on with?

- Where are you tense and where are you relaxed?

- Again there is no right or wrong, note what you're doing, consider it and experiment to find what works well for you.

These are subtly different, but they teach us about relaxing to allow a move to happen and then rapid engagement to control momentum.

They also raise awareness of where a move actually finishes and what efficient body positions are. It is not often the second your hand touches the hold.

Lock offs

- Find a steep section of wall with suitable holds

- Hang from straight arms with one foot on a hold – the further out or poorer the foothold the harder the exercise

- Let go with the arm on the same side – so if you have a left foot on let go with the left hand

- Hold for 3 seconds

- Put both hands on and pull up to a 90-degree lock

- Let go with the left arm again and hold for 3 seconds

- Put both hands on and pull up to a deeper (but comfortable) lock

- Hold for 3 seconds

- When doing this exercise think about maintaining the distance between your shoulder and ear – don't sag onto your shoulders or let it rise up

- When locking off allow your elbow to go out to the side, not in front of you.

- The difficulty should not be in maintaining the lock off as such (though this will feel hard) it should be about struggling to keep the foot on.

- Repeat on the other side

That's one set.

Toe touches

- Hang free from both arms (maintaining distance between shoulder and ear)

- Lift your left foot and touch and engage it on a low foothold out to the left for 1 second

- Release the foot and return to the start position

- Repeat on a foothold at a medium height

- Repeat on a high foothold

- Repeat on the other side

- Do not swing about. The foot raise and lower should be under control without momentum. Any swing should be stopped and controlled before moving again.

- That's one set

- You can do this with heels as well

Cross throughs

Essentially the same as toe touches but rather than using a foothold on the same side you step through in front of yourself i.e with your left leg reach across yourself and touch a hold on the right side of your body.

Off the wall exercises

There are thousands of core exercises and the only bad one is the one you do too much of. Keep with a set of exercises for 4-6 weeks then either change the protocol or change the exercises.

They should be supplementary to climbing to target a specific improvement or relative weakness.

These are a few that need no equipment (apart from a rope bag) and can be done pretty much anywhere.

I will group the exercises into static, rotational and power but these are broad definitions. They are exercises that bias that aspect more than others.

You can pretty much use the protocols provided with any exercise. You can do a static, rotational or power bridge for example. If you have some favourites keep with them but apply a different stimulus to your body by using different protocols.

The exercises and protocols are to give you some ideas to spark up your core routine and maybe make it more specific

If you're new to core training I'd suggest building a general core base first with the traditional exercises (such as the planks, superman, knee raises, crunches etc) then building strength through range with the rotationals and then try some power. Then up the level of intensity and go through the protocols again. Keep mixing it up to keep the training stimulus novel for your body.

There are many variations on these exercises to raise or decrease the intensity. As an example a side plank can be done on the elbow, straight arm, straight legs, bent legs, knees touching the floor, feet raised or any combination of the above.

It is also worth noting that the levels of core recruitment during weighted, compound, exercises such as deadlifting, squats, farmer's walks, split squats are huge. I haven't gone into them here as they require access to the equipment and I am trying to make this an article for as many people as possible.

One extra word on core training done from rings or bars. If you want to improve your recruitment and control, use rings. If you want to get stronger use a bar. Again a rough rule of thumb, but not a bad one. The unstable nature of the rings means we cannot load them to as high intensity for true strengthening.

1) Static

Plank, side plank, bridge etc

How do we make these intense and a bit more climbing-specific? Squeeze everything, hard!

There is a technique known as irradiation where the recruitment of additional muscles helps increase the recruitment of the target muscles. Squeeze a fist as hard as you can, with your focus just on the fist, and compare that to squeezing as hard as you can with a tensed arm, shoulder, abs and digging into the ground with your feet.

We do this a lot in climbing – this is the tension that links our hands to our feet and keeps us on the wall.

2) Rotational – or anti-rotational

These are interchangeable as when you rotate in one direction the opposing muscles are working in an anti-rotational fashion.

Shoulder taps

- Hold a plank position that is the correct intensity for you

- Slowly raise a hand from the floor to touch your opposite shoulder

- Slowly replace it on the floor and repeat on the other side

- That's 1 repetition

- You can place objects to reach for and place on the opposite side, which you then reverse with the other arm, to add an extra element of movement

Bridge with rotation

- Hold a bridge position of suitable intensity

- Hold an object with straight arms directly above you – a rope bag is used here but it could be a water bottle etc. You can bend your arms to reduce the leverage and make it easier.

- In control lower the weight to touch the floor at the side of you

- Return to the middle and repeat on the other side

- That's 1 repetition

Dead bugs

There are many dead bug variations. I'd encourage you to give them a google. They're a fantastic, equipment-free, high-intensity core exercise and a great one to do after climbing to finish your core off.

Lunge with rotations

- Take a small step forwards

- Hold a weight directly out in front of you

- Rotate as far as you can one way and then the other

- Return to the middle

- That is one rep

- Move slowly and with control

Plank with bag drag

- Hold a plank position of suitable intensity with an object/weight out to one side

- With the opposite hand reach through and drag the weight to place it on the opposite side.

- Swap hands and repeat on the other side

- That's one rep

Plank with leg tap

- Hold a plank position of suitable intensity

- Raise one heel towards the ceiling as high as you can without your hips twisting or back rolling

- Keeping the same height take the leg out to the side as far as you can

- Now slowly lower the foot to touch the toes on the floor, raise the foot and reverse the movement to the start position.

- Repeat on the other side

- That's one rep

3) Power

Bag slam

- Grab the rope bag and quickly raise it over your head to your maximum height – go right up onto your toes

- Focus on slamming it down into the ground with real intent

- That's one rep

Rotational Bag Toss

The seated version is shown here. It can also be done in standing, half kneeling and kneeling.

- In a seated position place the bag on one side of you

- Pick it up and with as much force and intent as you can throw it (preferably into a nearby wall)

- Repeat on the other side

- That's one rep

Combinations

This is given as an idea of how an exercise can be made to be about all aspects of core movement and control

Walkouts

- Start in a plank position and walk your hands as close as you can to your feet

- Now walk your hands away from you as far as you can without losing the tension in your body

- That's one rep

You can pause at each hand movement for 3 seconds, move as slowly as you can, reach through to touch as far as you can on the opposite side on each move or go fast and powerful to try and take off from the floor with each move.

The possibilities are endless with core and there are no wasted movements to train. So et your imagination run wild. Play with the movement, work hard, experiment and think about why you are doing what you are doing? Is it achieving what you want it to?

Protocol ideas

Whilst this isn't a physio-based article it seems a good place to get on my soap box and try and lay some myths to rest with what we know now compared to when the core concept and core stability became a thing, particularly in relation to lower back pain.

Core stability implies if we don't have a certain level of ability, performance or control our core is unstable. That sounds dangerous! This implied negativity is known as a nocebo. The opposite of placebo. Placebo is very powerful. How many people do you know who lift things in a certain way or engage their Transverse Abs to protect their spines?

The myth of core stability has been challenged and proven to not be a concept (at least not in the way it is sold as a nocebo) since 2007 (REF). But myths stick around. Especially when businesses are built on them.

If you wish to start looking at what the science says, in an easy to digest way, I can recommend googling 'core' and 'Greg Lehman' and 'Adam Meakins' (he's a bit forthright and sweary but always backs up what he claims).

The most common myth, that strengthening and/or engaging Transverse Abs protects your lumbar spine, has been absolutely refuted now. The original study never even said that it was an issue (REF). The fitness and therapy industries did. This was the start of the movement to "strengthen the core to protect the lower back". This myth works both ways. Strengthening a sore lower back does not actually automatically fix it or prevent future re-occurrence. It is way more complicated than that.

The original study didn't even mention weakness. It focussed on timing. That's where the idea of the tummy button sucking Trans Abs bracing movements came in. Even this has now been disproved (see the Lederman paper above).

But we don't remain certain. After all, we have been certain about ultrasound and core stability – you may notice ultrasound is not performed by NHS Physio's now. Science changes constantly. A recent meta-analysis (Hayden, 2021) showed that pilates was the only intervention that consistently reached statistically significant results. Yet that has a huge focus on 'bracing' before moving. So why is it successful? I think because it's a controllable way in. It has a perception of safety to a condition (non-specific lower back pain) that causes a great deal of anxiety. It's easy to do anywhere. It gives the patient control and it can also be done in a group, which adds social benefits and the chance to meet people in the same situation. It's much more nuanced and complicated than strength and control alone.

We do know we don't need to be in fear of our core stability. But if we introduce a new core routine we should do so gradually and carefully. If we don't we should expect niggles, reactions and possible injury. Just the same as any part of the body that you take beyond its current level of ability. The core and lower back are no different. They will adapt and become more robust, even if the form is not 'perfect'. But they must be given the time and the stimulus to do so.

As a climber, climbing coach and physiotherapist (who has also done a fair bit of running and cycling), Andy is ideally placed to provide clarity and direction to your return to climbing and outdoor sports.

A life long climber, who started coaching 13 years ago, he has coached on Spanish performance improvement holidays, sport climbing, competition climbing and helped people achieve everything from ascents of El Cap to their first V11. More recently he founded a youth competition climbing squad https://processcoaching.me/ with his business partner Ellie.

Whilst his focus in coaching is technique based, his passion in physiotherapy is education, strengthening and a detailed, fully supported, return to sport. This background enables a unique, blended, treatment approach, with an in-depth knowledge of all aspects of how climbing impacts the body.

Andy is spending his time writing a book about rehab for climbers - watch this space.

Comments

Core strength is needed to climb at Malham and some steep-ish grit crags.