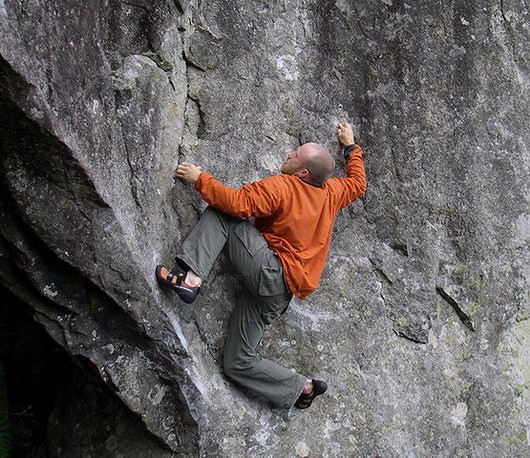

For many the greatest satisfaction in their climbing comes from that elusive feeling of moving smoothly and lightly across difficult terrain. But when searching for improvement, it is all too easy to focus on the task of increasing strength and fitness and hope that good technique will somehow happen unprompted given sufficient mileage.

Climbing movement is really important. Our delicate fingers and slender forearms can only take the majority of our body weight for a very short period, so if we are not moving as efficiently as possible, all the time, our prospects of climbing success are dramatically limited.

But changing the way you move on rock is no small matter. In the next three sections I'll attempt to explain how you learnt to climb the way you do, becoming aware of the way you move, and how to change your movement.

Part 1: Know Thyself

To improve your climbing technique, firstly you must understand how you learn movement, and secondly analyse how you move at the moment, so that you can modify your technique to achieve your climbing goals and reduce the risk of injury.

I learnt all this the hard way, after my appalling wall-bred, static strength-based style contributed to shoulder injuries that prevented me from climbing more than once weekly for 4 years. It took this period of enforced down-time (including double shoulder surgery) for me to figure it out, save yourself the trouble and read on to find out how to get better, without needing get fitter!

Beginners Mind - how you learn to move

The science: To make any movement, information must be sent from your brain to the nerves that operate your muscles. This information travels along neural pathways. All the time we are conducting complex movements involving many muscles and numerous pathways are being travelled simultaneously, from sitting upright to operating a mouse.

These movements that now seem natural had to be learned, the neural pathways had to be 'discovered' and travelled regularly by your brain signals before you were confident and relaxed whilst performing them.

Creatures Of Habit -how your movement develops

Initially these neural pathways are like a rarely travelled footpath - overgrown, hard to find and bramble-ridden. With increased traffic they broaden into a large path, then a track. If enough traffic passes through, the (Brain) Council will tarmac the track, and given years of heavy use, it'll become a five-lane super-highway.

Our habits employ neural superhighways – those movements we make all the time because they feel easy and familiar. We often do them without even realising it. Some of the many common climbing bad habits include: repeated repositioning of the foot on every hold; flagging on one side regularly, and avoiding it on the other; or crimping holds only because it feels more secure than open-handing them.

The more developed the pathway is, the less mental effort - 'brain bandwidth' - it takes to use it. That's why after the initial mental overload, the complex task of driving a car gradually becomes less demanding, and soon you begin to find room to think about other things, as your driving technique becomes a 'habit'.

Stress, either mental (e.g. fear of falling, social/performance anxiety) or physical (the unrelenting pump) interferes with your ability to use neural pathways. Our brains have a very limited bandwidth for conscious thought. If this is inundated with stress alarms, your brain automatically opts for the most well travelled neural pathways (habits) for movement, because they require less bandwidth to perform.

Fascinating, I hear you say.

But wait! What this means for the climber under stress is they revert to using the 'habitual' moves they've repeated the most before – often those front-on, over-gripping, foot bashing moves you've done every time you got stressed since starting the sport. Sound familiar?

Part 2: Repetition and Feedback

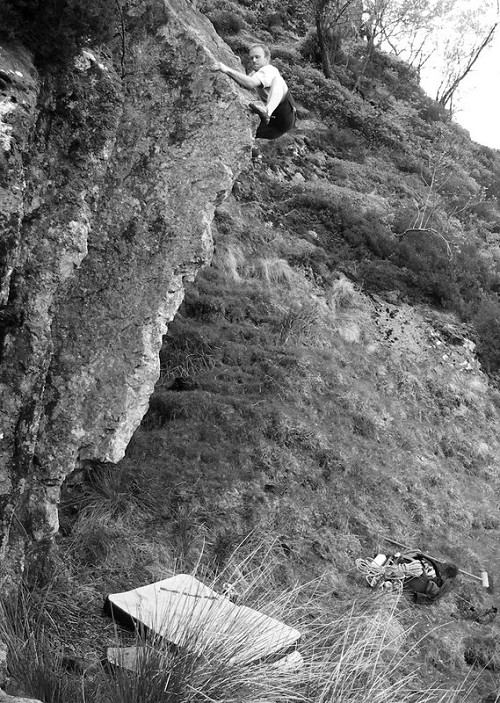

So movement is reinforced through repetition – to make those graceful moves work for you, you must repeat them numerous times, and gradually stress-proof them by progressively taking them from the security of a top rope or crash-matted bouldering room into increasingly demanding environments; pumpier, riskier and higher pressure. Thoroughly developed neural pathways can be operated at a subconscious level by the brain, so you can focus on the other issues troubling you mid-climb without your technique suffering. It often looks unexpected when a top competition climber falls, because their movement does not degenerate as they become exhausted, their arms may be screaming and their eyes popping out, but the subconscious is still wombling away pulling smooth moves out the bag – moves they have rehearsed countless times.

The Bad News

Unfortunately it's not just your best moves that get reinforced, it's every move, every time you do it. Damn! When you're seconding, cold and rushing to get to the belay, you're reinforcing those neural pathways of hasty movement and careless footwork. When – for the sake of fitness - you get back on the yellow traverse you cruised earlier that evening, and flail your way exhausted through it, you are further ingraining those wild and sketchy manoeuvres. As you hang from a fingerboard, or campus up the rungs, the pathways that focus on pulling really hard while your feet dangle uselessly are reinforced. These last two training methods are effective supplements for climbing, but if used as replacements you can see their effect on your technique may be detrimental.

To find out how you move, you need to get some feedback. You receive enormous amounts of feedback from your body every time you climb, but it takes time and effort to tune in to it, and use it effectively. Here's a recording I made of body-brain feedback from a climber who's just slumped exhausted onto the seventh bolt of a 6b+:

Body (screaming): "My forearms are pumped solid!!"

Brain: "Thanks for the feedback, I guess I failed because I'm not fit enough - better do more endurance training"

In this case Brain only listened to the loudest feedback – so concluded that fitness was at fault. In fact if every move up to that bolt had been executed in a more efficient style, and every slight shakeout exploited, the arms would have still been fresh, and the route completed easily within the existing fitness level.

So tuning in to the quieter body feedback is essential – how much your hips twist during a long reach, how straight your arms are, how hard your left toe pulls in while your right hand moves, how much your core swings after you grab the sloper..

The information is all there but to exploit it takes deliberate reviewing and a purposefully developed awareness of your whole body during climbing.

Using internal feedback is only half the story – you'll learn faster if external feedback is also listened to. This can be from any external source, usually fellow climbers, a coach, or video footage. Fellow climbers' feedback will be based upon their own experience, so consider the depth of this when taking it in: Are their high performances in the same arena as yours – and are they indoors or out, all-rounder or specialist?

Seeing yourself climb on video is invaluable but - be warned - it is brutally honest, and as it gives you all the information it can be hard to pluck the most useful points out. A good coach should combine the perceptiveness of video with the delicate and relevant feedback of a highly experienced friend, so you get a manageable dose of the right information. This can save you years of misguided time and effort, but unfortunately you have to pay for it!

So you've gathered this vast array of feedback, but now what to do with it? In Part 3 we'll tackle the process of changing your moves for the better.

Part 3: Getting Better All The Time - how to modify your movement

Having decided that you don't currently climb like a gecko/lemur hybrid, how to go about hatching out of that chrysalis and fluttering up the crag?

With the help of your feedback-gathering techniques mention in the previous article, you will no doubt become aware of a few habits, or neural super-highways. The aim is to neglect these tired favourites and focus on all the weird and unfamiliar elements of climbing that your subconscious has been avoiding all this time, until they become super-highways too. The eventual outcome of honing these is - when faced with a tricky move under stress - you'll choose the most efficient way to climb it from a huge selection of stress-proofed options in your repertoire, rather than grabbing an old favourite that may make the move much harder than it needs to be.

So get the strimmer onto those overgrown neural pathways and start deadpointing, fist jamming, and drop kneeing without delay! Whatever you've avoided, master it and you'll improve much faster that chipping away at a technique you have already spent years refining. Finding out what you avoid is not as easy as it sounds, we all avoid some things consciously (offwidth anyone?) but it takes careful attention to feedback to pick up which side you avoid flagging on, or which foot you avoid rocking over onto. These are both examples of left/right favouritism and it's a good place to start.

You need both a high volume of practice and it needs to be of a high quality for you to make steady gains in climbing technique. It is generally agreed that in order to perform at an elite level requires ten thousand, yes 10,000 hours of high quality practice. That's about 10 years at 2-3 hours of daily practice. Phew. You can't move the genetic ceiling (that decides the fitness for climbing) of your body, but anyone can clock up the practice hours if suitably motivated, and there isn't one elite climber out there that hasn't put it those hours.

Quality Street

So the volume of practice is directly linked to your climbing performance. The quality is equally important. When an elite athlete practices, everything they practice is solely for one reason – to get better. This level of focus can lead to a seriously unsociable climber (if you cannot find others equally focused), but with a little thought you can steer your climbing more directly towards improvement without dropping off the social radar for a decade. Alongside targeting your neglected moves, make sure everything is practiced on as many different wall angles and rock types as possible. When climbing indoors I rehearse unfamiliar moves on huge holds on the bouldering wall, then repeat them countless times at differing angles on 'rainbow' on the auto-belay, progress from here to harder bouldering and indoor leading. Begin stress-proofing as you feel more confident with them. Whilst training technique your agenda is simply to improve your movement. This means the grades, style of ascent, and 'getting to the top' habits are irrelevant –save them for when you're performing, and know the difference. Keep returning to the video camera and seeking feedback from all sources, and keep asking yourself if your practice is still purposeful, and taking you directly towards your goals.

Go To It!

It is never too early- or too late - in your climbing career to focus on your movement, great climbers are those that move well first, and then get fit/strong later. Although there is lots of information out there about what makes 'good technique', the bottom line is it's about what is most efficient for you - your build, flexibility and body shape. Only blame you failures on fitness as a last resort, be creative and experimental in your movement, and embrace the process of problem-solving moves.

Before you know it you'll be carefully orchestrating those 'at one with the rock' sensations, rather than wondering why they happened.

About the author:

John Kettle coaches and guides climbing from Kendal, Cumbria and can usually be found parenting or mountain biking when not on the rock.

- His website is: johnkettle.com

Comments