Mark Reeves shares some tips on sea cliff climbing safety, written in conjunction with the RNLI crew at Holyhead lifeboat station.

The UK is almost unique in the sheer variety of sea cliff climbing it has. Whether you are having your first adventure on Sennen Cove's single pitch granite cliffs or making an ascent of your 100th route at the much more serious Gogarth, all sea cliffs have a few things in common in terms of added risks involved.

These revolve around the big unforgiving sea at their base; it can block off retreat, make access difficult, wash you off the cliff and even drown you should you fall in. This article is about how to become more aware of the maritime environment and how you can help yourself quite literally avoid jumping in at the deep end.

Tides

Tides are affected by many things, the most important are the sun, moon and major planets. The biggest influence is the moon, though. Essentially as it waxes and wanes, it becomes in line and out of line with the sun and causes variations in the range of the tide.

So whilst the tide will go in and out every 5 hours or so, the amount it goes in and out depends on the state of the moon. The big tides are called spring and the smaller tides neap. Often sea cliffs are described as accessible for a certain number of hours around low tide. This will of course vary depending on whether it is spring or neap - some cliffs for instance are accessible at all but the highest of spring tides, whereas others need a low spring.

There are various online resources to help you learn to tell what the tide is.

If you look at the tidal curve, it is not a straight line in that the tide does not come in at a steady rate. The tide instead tends to hang either in or out for a long time and then start to come in slowly at first, but it will eventually start to rush in. Knowing this will mean that your belayer who is stuck at the bottom of the cliff may well start hurrying you up if you have not planned the tides right.

Swell and Wash

On the water margin there is a real danger of getting hit by swell. Often we have to traverse just above sea level in order to stay dry whilst the waves crash against the base. The first thing to do is realise that not all sea cliffs require you to get so close to the sea. So if there is a big sea running, avoid sea level traverses or abseil straight into a hanging belay above the wash.

I have had to do this at Castell Helen a few times, only doing the top pitches as the waves were crashing and nearly reaching the girdle ledge. It made for a very exciting climb, as we had front row seats for the shock and awe of the power of the sea.

However, even this is avoidable, as scientists have developed swell forecasting. The easiest way to access this is through a site called magicseaweed.com whose focus is on forecasting good surf. The forecast gives a swell height and period. Whilst both are important it is the combination of a large swell and long period between waves that will make for the most dramatic and troublesome states, as the time between waves essentially helps make the waves more powerful for their size.

Even if the swell is small and you feel you can make it along the base of a crag you need to remember the rule of the 7s. This is a rule of thumb in that the 7th wave is often bigger. Whilst this seems very crude, ask any surfer and they will tell you that waves do come in sets, so if you find yourself in a nice elevated place with a short low traverse ahead, spend time to watch the waves. Wait for the sets which often come as three bigger waves, then go. There are also occasional freak waves that are much bigger than the rest of the waves. Just pray you are not exposed when one of these comes in.

At Gogarth main cliff, we also have the added problem of the wash from the high speed ferry. This causes a kind of tidal wave that arrives silently about 10 minutes after you see the ferry pass. If you are in a narrow dawn then the sea can rise 4 to 6 ft easily. So keep an eye out...

Falling In

There are many reasons you might end up in the sea. You could get washed off by a wave, be that a freak one or the ferry wake. A simple slip on seaweed might cause you to end up in the drink or in the worse case scenario you might fall off before you get to a runner, hit the water and become instantly disorientated.

Either way the water is going to be a lot colder than you want it to be. This can instantly cause cold water shock. It feels like the air has been sucked from your lungs and panic sets in instantly. The trick is to try and fight the panic and force yourself to breathe normally. However, for some the constriction of the blood vessels in the skin and the extra pressure from the water which increases blood pressure coupled with increased heart rate means some people can suffer heart attacks or strokes in this stage. The uncontrollable urge to breathe rapidly means you also lose breath control in these first few minutes, which in rough water can lead to you inhaling water.

If you get over this initial shock then you also have to deal with trying to swim - not only fully clothed, but with a rack of climbing gear attached to your harness, all of which will be pulling you down. Even a strong swimmer will find it difficult to remain afloat for too long in this condition. If you rack up using a bandolier in serious situations, this can be ditched into the sea immediately. However, if you rack up on your harness you may well have to start discarding the heaviest items to help your survival.

To climbers this may be too much to bear, but if you have fallen into a big sea, you need to give yourself every chance. So forget the cost and ditch the rack. The RNLI find that whilst most swimmers and kayakers will be fine if they fall in, it's the people who end up in the water unexpected that are in the most danger as they are not prepared to swim for their life.

All the while as you recover from the shock your body will slowly be reducing the heart and breathing rate and with it comes a slow and steady decline in muscular strength, resulting in an inability to swim and a rapid decline in core body temperatures leading to hypothermia and eventually unconsciousness.

In those initial minutes you need to make a plan. If the base of the cliff is being battered by the waves, can you get out there? Did you see a sheltered section? Will you have to try and time your landing with the swell? Can you swim in feet first to try and fend off the rock? Remember in an 8ft sea you might be level with a hold one second and 8ft below it the next!

Prepare yourself briefly before you traverse and consider what you would do if you were to be washed in the sea. Have an escape plan and perhaps only have one of you in harm's way at a time. Also consider that bandolier for quick release of the rack.

If you are not the person in the sea, remember that diving in is the last resort, and even then consider the idea that no matter how good a swimmer you are, there might be two dead people in the water before long. Can you talk the person to safety, reach them with something like the rope as a throw-line? Can you make yourself safe to the land and wade in to assist the person ashore? Really think more than twice before you dive in Baywatch-style in anything other than ideal conditions.

Sea Cliff Rescues

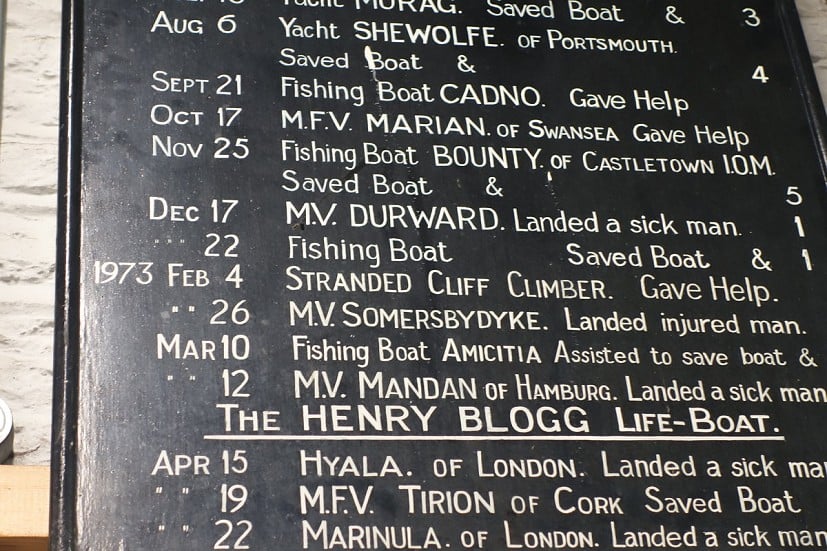

If you do have an accident at a sea cliff, you have to remember that you are going to be rescued by a combination of emergency services who are generally not rock climbers. First off you need ask for The Coastguard, not the police and mountain rescue like you would onshore. Whilst the Coastguard do have cliff rescue capabilities and helicopters that can be tasked, they will often be assisted by the RNLI. Whilst it may seem totally sensible that you know you are on Dinosaur on the Main Cliff of Gogarth or Kitten Claws on Carreg Y Barcud, your rescuers may not necessarily know exactly where the cliff is, let alone the route.

On a recent trip out with the active crew from Holyhead lifeboats, they suggested that bright coloured clothing and a torch would help them locate you from the sea, so by the time they are usually tasked dusk is close at hand. Having a UK grid reference or a Lat/Long for your cliff will help the proceedings, as will sharing the colour of your clothing to help identify you specifically.

Don't be the next 127 hours victim, although if you do survive write a best seller. Remember through: simply letting someone know where you are and what you are doing will speed up any rescue.

Problem Avoidance and Self Rescue

When we are sea cliff climbing, we really do need to be a bit more self-reliant. First off, in general you really don’t want to be pushing your grade the first time you visit a sea cliff, as most cliffs are not simple walk in, walk out affairs, meaning that you need to be sure you can climb back up to the top once you have descended. Given the blind nature of simply finding a sea cliff from above, you might consider going with someone already acquainted with the cliff on your first visit, even if it is just to identify the access points.

If you are abseiling in, then it is recommended that you leave your abseil rope in place. The reason for this is it gives you a Plan B other than swimming to the nearest beach if you can’t make it back out. With this in mind you will also need a couple of Prusik with you and the knowledge of how to ascend a rope with them whilst backing yourself up with a rolling clove hitch below, as no one wants to hang on two pieces of 6mm cord for 50 metres.

These Prusiks will also help if you injure the second, as many climbers have been hit by falling rock that their partners have knocked off at sea cliffs, because the nature of the rock often means it is friable. As such, it would be good to know how to perform a hoist of some kind or other basic rope rescues.

The other incident in which the Prusik can help you is if you are following your friend up something too hard for you and you find yourself hanging in space unable to touch the rock to climb up to them - you would then have to Prusik up the climbing rope. This has only happened to me once and I was caught twixt the devil and the deep blue sea, which was raging at the time.

More information on self rescue techniques in this article.

Take Home Points

- Know the tide and the swell

- Avoid falling in and have a plan if you do

- Don’t increase the number of casualties by diving in

- Wear bright clothes

- Take a torch/charged phone

- Consider using a bandolier

- Leave abseil ropes in place

- Stay within your grade at first

- Have prussics and know how to use them

- Leave word of where you are going and when you plan on returning

- PRESS RELEASE: 30-Week Instructor Training 2020/21 19 Jun, 2020

- Sunnier Climbs - Hot Rock holidays 25 Jun, 2019

- ARTICLE: Avalanche Basics Part 2: Staying Safe 20 Mar, 2019

- SKILLS: Avalanche Basics Part 1: Anatomy of an Avalanche 15 Mar, 2019

- New North Wales Rock Climbing iPhone Guide 30 Nov, 2011

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Llanberis Slate - The Full Tour 30 May, 2011

- Llanberis Mountain Film Festival 22 Mar, 2011

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Tremadog - North Wales 26 Oct, 2010

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Llanberis Pass 4 Mar, 2010

- Bardsey Ripple Sundae 7 Dec, 2009

Comments