Eben Myrddin Muse writes about South Wales' lesser-known sandstone cliffs and quarries, with sport, trad, and bouldering on offer.

South East Wales: The Sandstone

What comes to mind when you think of 'South Wales Climbing'? Perhaps the soaring walls and crashing waves of Pembrokeshire, or the long beaches and sunny coves of the Gower; the sandstone is probably not what comes to mind for most. In lists of climbing-friendly cities, Cardiff, Swansea or Newport might even be entirely absent! This needs to change because when you pull back the curtain, there's a vast quantity of wonderful crags - big and small, busy and quiet - that you should visit. Whether you're looking for a hard sport project, an afternoon of bouldering, or a full day of ticking at your comfort grade, the post-industrial landscape of South East Wales and the valleys just keeps on giving.

Rich veins - from coal to cragging

The South Wales Valleys have never had an easy ride. From the dawn of the coal industry in the 1800s to the final closure of the last deep-coal mine of Tower Colliery in 2008, they've endured and withstood strikes, closures, highly concentrated extreme wealth, widespread poverty, and incalculable tragedy over the years. Many who live in the metropolitan or urban areas of Wales live parallel lives, with little to no connection with the surrounding areas - the areas whose mineral wealth inhabitants paved and built places like Cardiff, Swansea and Newport, in a figurative and literal sense.

As a student arriving from North Wales, climbing gave me a sorely-needed reason to leave the city behind and see a part of South Wales that's never been put on the pedestal of Pembrokeshire, Eryri, the Gower Penninsula, or the Brecon Beacons. The regular spread of population throughout the valleys means that you'll often be met by bemused local residents, youths, often curious about the idea that the 'adventurous' mountain sport of rock climbing happens in their backyard. More and more, locals are getting involved in the sport, and taking ownership here, with the Split Tips and Grit Climbing (yes, we have grit too… sort of) being great examples of what happens when local entrepreneurship meets extreme enthusiasm and a strong community spirit.

This landscape is pocked with the scars of industry, with quarries providing the perfect medium for exploration. From modest natural outcrops with beautiful aspects to jungle-esque wild pits framed by towering, sheer walls of characteristic orange sandstone, there is a wealth of climbing to be found here, with definitively the best crimps on the planet (trust me). With no less than four modern guidebooks now describing the area (two bouldering, one sport, and one sport/trad) there's never been a better time to get familiar with South Wales sandstone!

There are (according to UKC) at least 81 known sandstone crags in the sandstone valleys within 40km of the muddy shores of Cardiff - most are within a forty-minute drive, or even better, a relatively short train-ride away on the valleys line. The rattly ride up on the old 1980s era Pacer trains was a rite of passage for decades, but long-awaited investment in infrastructure means that the present-day traveller can enjoy such luxuries as air conditioning and semi-functioning toilets as the smooth carriage drops you off, in some cases, within a few yards of the crag! Rob McGurk recalls life as a personal transport starved student in the early 2010s, stepping off the train, and into the crag:

Even when nothing else was in nick, I remember time snatched in the early morning, before lectures, working the technical crimp-fests on 'Gorki's' wall. My climbing apprenticeship was served here, along with Nav' Quarry, Treherbert, Bargoed, Penallta, the Gap... the list goes on. While these crags are somewhat scrappy, and graffiti and litter are not uncommon, the experience of hopping on a train, leaving the city behind and getting out on the sandstone was pure bliss. Keen/skint students like myself could get an incredible amount of mileage on real rock - in some cases the crags are easier to get to than the nearest indoor wall!

- Rob McGurk, sandstone enthusiast.

For those crags that are a little further off the beaten track, the journey can take you to some unexpectedly beautiful and fascinating areas. The rugged beauty of the South Wales Valleys can't be overstated - it only takes you only one sunset walk up to the top of The Gap to gaze down on Treharris and the Bargoed Valley to be enthralled.

Although some could (quite fairly, I suppose) describe the quarried crags as industrial scars on the landscape - pock marks from the past - they are also often textbook examples of regeneration and nature revival, as well as being near some amazing feats of architecture and industry. Old chimney stacks, lift cages, viaducts and railway lines scatter the landscape. It's also not uncommon to see a raven or a Peregrine falcon soaring above (if you yourself encounter any nesting birds please contact your local access representative!), or intrepid creatures such as the green tiger beetle, unique butterflies, or rare staghorn ferns and ivy leaved bellflowers. There's also a real charm to some of the formations that were left behind by the quarryman's pick, from the teetering tower of Rhondda Pillar to the sheltered amphitheatre of Navigation Quarry.

The grey-red Pennant Sandstone that lay as mantle over the vast coal fields has a storied history in the construction of South Wales as it is today, from the sprawling workers' terraces of South Wales to the zany battlements of Caerphilly castle. It's partly from the insatiable need for the former, as industry grew, that countless quarries spring (I'm inside a classic pennant sandstone mouldy terrace house™ typing this article right now).

When quarried, the rock that's left behind forms sheer vertical walls, weathering in rare pockets, slots, or square, thin edges that challenge both finger pulp, skin, and footwork. For the natural crags weathered by time, flared cracks and wide sloping edges are the norm. Though some claim that the rock here is choss - this is untrue! The rock here was quarried precisely for its strong anti-weathering properties and resistance to the elements! So there, that's settled! Any so-called "choss" just requires a little more traffic…

Sandstone Climbing: The Early Days

Climbers have been reaping the rewards of South Wales rock since the 60s, and it's been host to a great number of intrepid developers over the years. Goi Ashmore, who was active from the 90s to the present, recalls that busy time, as new bolting practices, new crags, and a spree of retro-bolting ushered in a new era of sport climbing on South Wales Sandstone:

I arrived in South Wales in 1990 coming down to do my master's degree in Cardiff. There were only a few known sandstone crags, from the '83 guide, I think Penallta and The Darren, although there were hints of potential at places like Llanbradach. I had the Mountain Magazine area reports that Roy Thomas had written, so we started to discover places like Cwmaman and Mountain Ash and found sport routes that Andy Sharp, Martin Crocker and Roy had established. The information was patchy but we managed to find the routes, repeat about 80% of them within 6 months and write our own guide.

The routes were mix-and-match – not fully equipped with bolts, maybe a couple of Troll 8mm bolts, a peg and a wire or two in 60ft, but it was clear that the ethos was moving in the direction of fully equipped routes, not the slate 'designer danger' direction. There was a lot of 'gear recycling', theft of pegs and removal of bolts going on.

In '94 Eugene Travers-Jones proposed a bolt policy, which wobbled through, despite some bitter hostility. The policy was designed to control bolting on Gower but crystallised the thinking on sandstone – the routes should be full sports routes with decent bolts and lower offs.

Things really took off then, with Roy and Gary (Gibson) developing new routes and re-equipping the old ones to the new standard. I did a lot of re-equipping, and I nearly got into the habit of preserving the mistakes of the 80s – a crap legacy of mix and match, but by the end of the 90s anything re-equipped was done in full. What surprised me in the 90s was just how few people were out climbing in the area, but then when all the climbing walls started up, this ramped things up a notch and I think that's what's kept people developing the area. I've been surprised by how good some of the newer discoveries at places like Craig Cwm have been.

- Goi Ashmore, developer and South Wales veteran climber.

Gone are the days of the 'Roy Thomas Special' - a nub of aluminium pressed into shape by school children at detention - these days you are more likely to encounter a lovely stainless steel glue-in than a piece of modern art protecting your first clip (although a clip stick is very much recommended). The truth is that through pure hard work, sweat, and lots and lots of cleaning, this place has been transformed into a true sport climbing destination.

Quite a few routes climbed during the late 80s and 90s still offer a stern test, with stand-out routes including Contraband (7c) at Llanbradach, Mad at the Sun (7c) at the Gap, and Sharpy Unplugged (7b+) at the Darren. You won't find routes like them anywhere else, and that's a guarantee.

So, what's the climbing actually like?

Before I'd tried to climb any other kind of rock, it seemed natural to me that holds on any big face should be totally square, horizontally aligned, and cruelly placed at just the right distance to be challenging. The angle of the walls; only exceeding verticality to make way for short, muscular roofs. Immaculate friction, dynamic moves, and dramatic clefts splitting the faces like the impact of some mighty axe, just begging to be jammed.

It was only when I climbed at other places that I sort of realised that it wasn't all like this, wasn't all totally one-hundred-percent engaging, one-hundred-percent of the time. Mathew Wright of Lexicon fame (although not yet by the time I asked him to write something) knows a thing or two about rock, but here he fondly recalls his formative years on the good stuff down South:

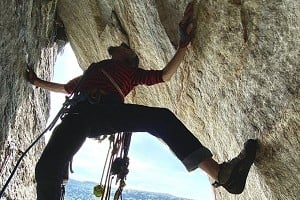

Since I first discovered climbing, South Wales Sandstone has remained one of my favourite climbing areas. The orange and grey bullet-hard ancient sandstone contrasts beautifully against the purple heather and greenery that surrounds many of these isolated and varied quarries.

The climbing itself is characterised by layer upon layer of these sedimentary sandstone sheets, each offering differently sized hand holds. You will often find that these holds form perfect 90 degree angles from the face, creating mostly large flat holds or downward pulling crimps.

Regardless of the grade that you climb, you will almost certainly find that the climbing on the ancient sandstone supplies minimal surface area, your toe rubber must nestle just right on the hold, and your focus must be channelled on the complex puzzle that awaits you. Each hold is exactly where it needs to be to make the move challenging, but never impossible, typically creating a floaty and sustained journey up the wall. Clipping the chains on a route is rewarding but never as satisfying as the experience that brings you there.

The way the rock forms is unique for its perfect face climbs. Each route presents a unique challenge of fine complexities, demanding perfect execution of dancing movement and fingers of steel. These challenges come at varying angles and in a range of features. This allows for adjustment to the overall grade, but generally, all routes are characterised by the iconic and unique minimalistic nature of the beautiful sandstone quarries. For every test you pass, you gain an improved understanding for your own individual skills when it comes to technical face climbing.

- Mathew Wright, 9a/V15/E11 climber, bit of a wad

I'm not saying it's the perfect formative style for throwing down E11, but maybe I am? Nonetheless, the style is uncompromising - there's sparse opportunity for open-handing, half arsed, static movement, or soft-tipped finger pads. There exists here a thick catalogue of climbing, from the easiest climbs to the test pieces at the top of the grade pyramid. Though not necessarily sandbagged, the climbing can feel challenging for the newcomer.

But what if I have an aversion to bolts? Well, while the most well-travelled lines follow the steel constellations up the cliff, there are still some stellar trad ticks, ready for an adventurous soul to come and breathe life into. For some, it's worth an abseil inspection before you go. My own personal trad highlights include the Pat Littlejohn solo classic of Scabs (E3 5b), picking its way on jugs and flakes through an unlikely overhang. Then there's the magnificent The Expansionist (E3 5b) at Llanbradach - truly Indian Creek's forgotten Welsh baby cousin. Then, there are more conventional pleasures such as The Owl and the Antelope (E2), a shining path of gear placements through otherwise totally unprotectable ground.

The point is, it's often well worth lugging the rack along with you (and the approaches are easy anyway, what are you complaining about?). Aside from traditional gems at sport crags, there are wholesale trad crags that can more than sustain a good day out - Cilfrew Edge is a great autumn/winter venue and the home of a high density of quality routes (plus a horrific/classic (?) offwidth, the well-named Throbbing Gristle (E3 5c)).

Not to forget about you pebble wrestlers - in a bustling scene that's seen new crags and problems multiplying like rabbits, there are stand out areas such as Melincourt Falls with its beautiful riverside setting. The base of many crags such as Treherbert Quarrry (Rhondda Pillar) and The Gap yield worthwhile problems, but then you have Neath Abbey Quarry: "the Fontainebleau of the Valleys". The crag that keeps on giving (and not only because the cliff is still actively moving downhill - some say it's reset more often than some of the local climbing walls).

Sandstone bouldering manages to condense all that's good about the sport climbing, except on a micro scale. Sequences and holds that would seem impossible in the middle of a sport climb suddenly become possible at -4 degrees celsius, at attempt number fifty-three. Desperate throws to a deadpoint edge, credit-card holds, screaming fingertips, worth it for that crucial tick... What more could you possibly want?

The Future

Despite no fewer than three guidebooks to South Wales being released in the last two years, they are all already somehow a bit out of date - some of them were the day they were published! Not from lack of due diligence on the part of the authors but due to the fact they were shooting a moving target: the ferocious work of local developers and their drills/brushes/boundless enthusiasm, the continued bouldering explorations (the race to release a South Wales Bouldering Guide Supplement is truly on) leave us with a growing resource that makes life as a climber in South East Wales sweeter every year. Another growing resource is; climbers! Hannah Roy, moved to Cardiff and started climbing a few years ago, and speaks to the changes they've observed in South East Wales since then.

I moved to Wales and started climbing in Cardiff, almost a decade ago. When I first arrived in South Wales I had little knowledge of the outdoor climbing world and was a plastic protagonist. I got myself a job at Cardiff's (at the time) only climbing centre and began to settle in. It wasn't long before I had my first taste of the outdoors and was instantly hooked. Climbing on rock was so much more rewarding, but the climbing scene back then was considerably smaller and meeting new climbing friends was hard. It wasn't a surprise to see an empty climbing centre some evenings. Unfortunately for me, life got in the way a bit - for several years I had to give climbing up.

Fast-forward to 2018 when I got back to Cardiff. I immediately reinstated my membership at Boulders and noticed a major difference in the scene. It'd only been a few years but it was RAMMED in there; climbing had become popular. Not a quiet evening to be seen (and yes, I was going every day for about a year when I first returned). There were so many new faces peppered in with the old.

It wasn't long before I developed a whole new friendship group centred around climbing. This new scene had a psyched, welcoming, atmosphere and the community as a whole was inviting and friendly. When Covid hit, as soon as the rules allowed for it, we were outside almost every day, discovering what South Wales has to offer. When the new guidebooks came out in 2021, I was surprised and delighted by just how much there is to explore.

As lockdowns slowly (even slower in Wales), eased and climbing outside became an option, people sort of began to realise how much they had been missing out on locally, and against that backdrop, development has reached a renaissance. I've barely scratched the surface and now I have the tools to dig deeper.

There's such a range of crags, and the most psyched scene. I love it here and can't wait to see the things develop. Look out Sheffield, we're coming for the title of climbing capital!

- Hannah Roy, South Wales local and candidate for 'world's keenest climber award'

When I started climbing here, it could be a grim task to cut your way through to the crag through the undergrowth, and sometimes even spotting the bolts through the grime and vegetation was near impossible. These days, the picture is different - as more climbers hit the crags there is also a greater degree of stewardship. Paths are well-trodden and maintained, rubbish often carried away, and nesting sites are reported and so protected.

The community has also started self-organising bolting workshops in order to pass on important skills to the next generation, and the Bolt Fund just bought itself a new drill (donate here). There will be crag-clean ups to join in the next few months, it's always a good idea to keep an eye out on the South Wales Climbing facebook page for volunteer calls. The result is that I rarely if ever pack my machete to clear my way to the crag these days, and that can only be a good thing for all!

The future is bright for South Wales Sandstone, so what are you waiting for?! Get yourself a copy of the guidebook or Rockfax App, and get crimping!

- OPINION: Right to Roam - An Idea Whose Time Has Come 27 Feb

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Tywodfaen De Cymru 26 Oct, 2022

- INTERVIEW: Roy Thomas 7 Apr, 2022

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Welsh Crack Climbs 16 Dec, 2021

Comments

Great article. Am keen to go back.

Mick

Not mentioned in the article but some of my favorite routes in Pembroke were on the sandstone seacliffs, such as Armorican (VS 4c).

North pembroke is far too civilised. This article is about grotty valleys sandstone, Gods own, mostly old quarry workings. Geographically different (or at least seems to be) than the bedding slabs of north Pembroke. Whilst it is at the southern end, I'd describe Pembroke as west wales rather than south wales.