Part 1: An Introduction

I always cringe a bit when people call it modern bouldering. Compared to what our closest relatives are capable of, even the funkiest human boulderers look static and rigid.

As our human ancestors spent 60 millions years as arboreal creatures, our locomotor system is designed for biped hand- assisted running, climbing and jumping in the trees. Rock - and nowadays climbing on artificial surfaces - is the contemporary expression of that in movement culture, but those capacities developed first to deal with tree trunks and branches.

In this three-part series, I'll try to shed some light on how to improve our modern bouldering skills.

Despite the popularity of climbing, research on its biomechanical aspects is rather in its infancy. I'm afraid that it will take quite a while before the average climber will be able to gain significant insight into his or her climbing by scientific biomechanical analyses. There are just too many factors involved in the motion of an object, so the set of equations to solve the problems and the solutions which arise are pretty complicated.

For the foreseeable future we'll have to identify the influencing factors in our climbing movements ourselves. To make sense of it all and to transfer what you learnt to similar situations, you need to understand the underlying principles.

Should you find my explanations lengthy, and if you're more interested in replicating the tricks and stunts you see on social media or in comps, these trick moves can be practised specifically and will certainly improve. The problem lies in transferring the trick you learned to a similar, but different movement puzzle.

Climbing is about movement tasks and challenges that require not only good physical attributes but also problem-solving abilities, adaptive thinking and mental control through the management of risk and fear. Unlike figure skating and gymnastics, where we arrive at a "one best strategy" through top-down, analytical methods, for climbing we need bottom-up experimentation.

Even a gentle twist of a hold can entirely change the ideal climbing solution. This is why blanket assumptions about the right way to climb are not helpful. Instead, I'll lay out the principles, so that you'll learn a thing or two about physical literacy, human motor learning and skill acquisition.

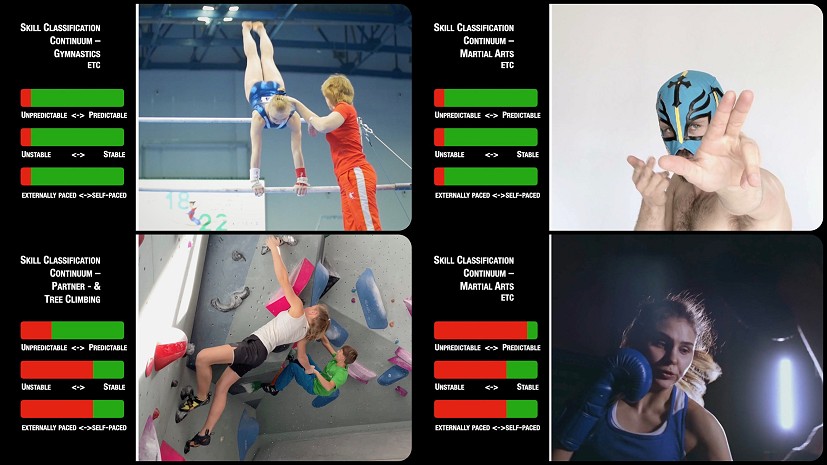

There are a large range of sporting activities ,each requiring a set of skills. Skills have many characteristics that can change in different situations, which makes classifying them difficult. Accepting that skills cannot be neatly labelled, we place them on a continuum.

The Open and Closed Continuum

This continuum is concerned with the effects of the environment on skills.

Closed skills take place in a stable, predictable environment in which the performer knows exactly what to do and when. Skills are not really affected by the environment and movements follow set patterns and have a clear beginning and end. The skills tend to be self-paced, like in gymnastics.

There is not a whole lot of ambiguity or uncertainty in these activities and athletes and coaches know exactly what they are doing. Rehearsed redpoint routes and speed climbing are considered closed-skill activities on this continuum.

Open skills on the other hand require movements to be continually adapted.

Onsight climbing and competing in climbing competitions are predominantly perceptual movement patterns that often requires fluid adjustments and variation of skill.

As any competitor knows all too well, our adaptability is compromised as our level of perceived stress increases. Thinking times are reduced and instinctual reactions increase.

In scenarios like this, apart form your climbing skills, adaptability is your most valuable asset.

Adaptability is the most valuable ability

When climbing you have to recognise when to continue your course, and when it's time for a change. This vitally important recognition and ability to make crisp, swift decisions in your best interest is called adaptability.

This is why I won't explicitly explain isolated climbing skills here.

Instead, I'll lay out the principles of quadrupedal vertical locomotion, so that you can than apply that knowledge in a variety of climbing situations, not just one (in Part 3).

The burden of climbing's dangerous past

For mountain guides, the safety of their clients is of uttermost importance. They will tell you exactly what to do and where to put your hands and feet. An alpine wall rarely is the right place to experiment with a double dyno far above your last piece of protection.

Many climbing coaches still teach climbing in a Closed-to-Open Progression, as if it still happens in the mountains and not in a safe modern bouldering gym. Often that is a top-down process, in which an all-knowing former mountain guide (now coach) teaches the novice how it's done.

The belief is that movements have developmental stages and should be "mastered" first and then put into open/chaotic environments.

In this coaching style, technically efficient movement comes first; exploring the environment comes later. This is a typical progression in a closed-to-open skill training program. The structure of this training program is often described as a seemingly linear process.

From my experience though, skill acquisition is more of a messy, non-linear process. It is very complex, there are multiple layers of possibility, and skills might appear and disappear depending on context and circumstance.

Athletes coming from top-down coaching often struggle with the flowy, momentum-based nature of modern bouldering. It is not only about how you have been coached (if at all) though, but also the mindset you are in.

For example, many competing athletes have become focused on the intention on the routesetter, allowing little room for their own adaptability, problem solving and creativity.

Unintended Beta

Beta is climbing jargon that designates information about a climb. The complexity of beta can range from a small hint about a difficult section to step-by-step instructions.

Often beta is talked of as though there is one ideal way for everybody to solve a boulder problem.

After analysing the last decade of modern bouldering comps, I don't see this being the case, though. Competitors make problems work for themselves with vastly different solutions. What "works" in each case and what leads to success depends entirely on the individual climber.

Moves emerge as a result of self-organisation when climbers are exposed to different levels of environmental complexity.

Rigidly classifying climbing technique or emphasising specific beta may ignore an individual's unique movement requirements to different solutions.

If you create rigid rules that only apply in certain situations - as in closed skills - or about the setter's presumed intentions, you will struggle when you encounter something unknown and new.

Become adaptable, not adapted

You can be successful on rehearsed climbs just by being adapted to the demands of that particular climb. For the immensely open field of modern bouldering, you need to be become adaptable.

As your coach, I would challenge and channel you to find your own movement solutions to the problems faced. By manipulating task constraints, I can direct you to acquire specific movement solutions.

This is the so-called Constraints-Led Approach, situational learning through manipulation of constraints, ensuring lots of variability in practice when learning.

In the next installment of this series I'll talk about the mental and cognitive aspects of modern bouldering and best practices of movement learning and skill acquisition.

Spatial and temporal aspects

Climbing is a physical activity performed against gravity. It is the combination of body movements created within the kinematic and kinetic parameters.

The fundamental mechanical interaction between the climber's centre of gravity and the supporting environment has spatial and temporal aspects to it.

When we climb well, movements of several limbs or body parts are combined in a manner that is well-timed, smooth, and efficient.

While spatial interaction is rather simple to observe, describe and learn, the temporal features of a locomotor task such as, for example inter- and intralimb timing are more difficult to understand.

For example, many climbers struggle with coordination for dynamic moves because of the speed-accuracy trade-off that is inherent in every movement.

In the third part of this series I will look into some spatial and temporal aspects of modern bouldering and give you some ideas of how to improve them.

Udo Neumann is the author of Performance Rock Climbing, Der XI. Grad and Lizenz zum Klettern. Recent video publications include 'Climbing Technique of the 21st Century' and the 'Ideas to improve your Climbing' series. From 2009 -2017 he was the German Bouldering Team coach with World- and European Champions to his credit. Today, he advises federations and teams and coaches athletes and coaches. Check out his YouTube channel.