The idea of going to El Potrero Chico, Mexico was agreed on. I got in touch with Peter to say I was going to be in North America between February and March. Wanting sunshine and multi-pitch sport climbing El Potrero kept coming up in discussions. Some people had been several years ago, others were still there with other friends having just come back. With a month left we agreed on the dates and planned to meet in Los Angeles to fly down together to Monterrey.

Driving south from Monterrey, past the highways, the caravans of eighteen wheelers, and the warehouses and factories of multinational corporations, the mountains rise up piece by piece from the landscape of broken concrete. Low, green, freestanding mountains to the west at first, the closest gutted by mining. To the east, more of the same: verdant, rounded, tame old mountains.

And then you see the end of the chain. Who raked away the green and exposed the limestone beneath into this ragged, fractal foot of swords and spires? Imagine taking the spiked harmonic frequency graph from a drum and bass track playing at a dance party of the gods, give it depth along the Z-axis, shade it grey, black, and tan, sharpen its edges, sprinkle it with cactus, and call it El Potrero Chico.

"The Little Paddock." Or so we were told. It doesn't feel little, not at first. Not when you enter the canyon and know that every few feet you walk takes you past the approach to a different four, or eight or, twenty-three pitch climbs up features of every description. On either side of you.

And that's just the rock. The backdrop, if you will, for the human volume that fills the canyon from dawn until well after dusk, when lights from the headlamps of ambitious climbers drop through the dark in thirty-five-metre rappels. All day the voices of climbers calling in English, Spanish, and Quebecois compete with the remixed metallic cries of the boat-tailed grackle, the little fanned-out raven-like creatures who congregate in the short trees of the canyon.

We arrive late Sunday morning, jet-lagged and eager. In the parlance of the young rope-draped Americans everywhere around us, "the stoke is high." We set up camp, brush off our jetlag with tacos and spring water, and set off in the heat to start our week of climbing.

Sunday might be the worst day to arrive in EPC. It sets your expectations too high. If you arrive on a Sunday expecting to find the template for the week that follows, you will only be disappointed when the fiesta fails to rematerialise on each subsequent day.

A few pickup trucks have already established their claims when we arrive, parking in little clusters and blaring their own blend of traditional and popular music, all refreshingly in Spanish. Next came the barbeques. The children. The ballgames. A steady trickle of cars, trucks, and motorbikes continues unabated all afternoon and evening until the tired climber walks back at night through the souped-up cars' carnival lights and sounds of self-contained multigenerational revelry, smiles flashing from the dark with half-amused "holas" and "buenos noches." There are women who ride up and down the dry riverbed on horses. On actual horses. They look like actual cowboys. Nobody bats an eye.

Throughout the day, the carnival continues above the canyon floor. And the climbers are the least festive of the crowd. A hundred meters off the ground, the beautifully tanned and toned youths who have driven down from Austin cluster in rock top nests with snacks and books and house music on tiny speakers and watch as their friends practice crossing the massive slacklines they have webbed across the canyon. The fifty-metre line, the eighty-metre line, the one-hundred and twenty-metre line. With grace and patience, they explain the mechanics of their systems, only to flounder for words when trying to describe what all the driving and planning and preparation builds to: the feel of the line under their feet, the transmission of waves through material and body, the falling, the hanging, the chasm. Ineffable.

The next day only a few straggling cars and trucks -- perhaps too drunk to drive home safely, or perhaps returned in the morning to catch the last undissolved wisps of the preceding night's festivities -- remain, with insistent laughter and music. The kids from Texas take down their lines. The grackles are still in the trees. The climbers return to the rock.

Within this easy cycle, the passage of days is marked mostly by the extracurricular activities: market days in Hidalgo on Tuesdays and Fridays, where the produce from California and Mexico is arranged between stalls selling street foods fried in woks over fifty gallon drums on one side, and the women intent on their tarot card bingo games on the other; a temazcal sweat lodge at the campgrounds saved from touristic profanity by the sincerity of organizers and participants alike; a movie night; midnight drives through the canyon; the daily coming and going of climbers. It's easy to fall onto the see-saw of seeing so many kindred spirits moving in and out of your life, easier still to smile and let them go.

And in this wonderful time out of time things can change. So it is with climbing.

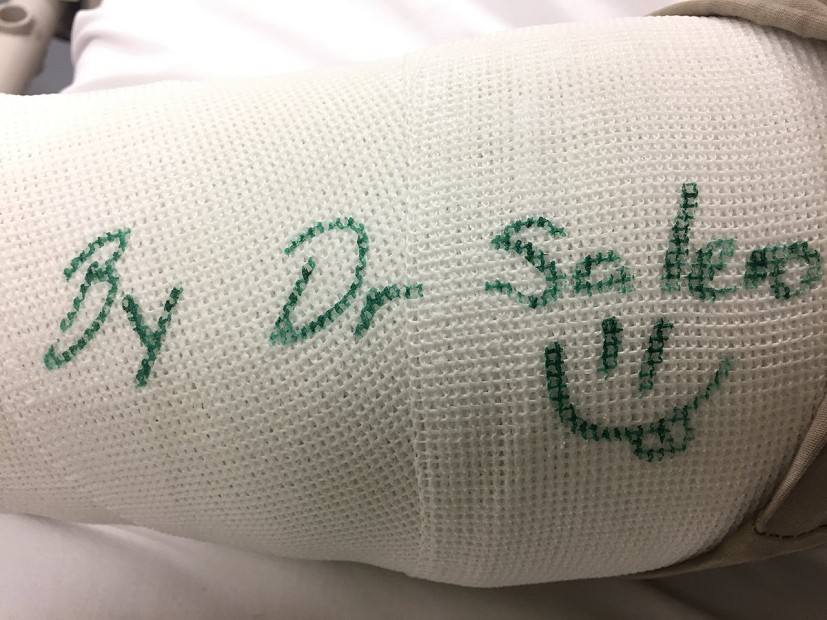

The fall happened on the 7th pitch of Space Boyz (5.10c) on the Jungle Wall, about two-thirds of the way up the pitch.

I'd like for what I learned from the fall I took towards the end of our trip to El Potrero to help other climbers avoid injury, along with the pain and disruption that follow. I'll give a brief description of the fall itself, and then describe some of the factors which I think contributed to it.

Jake and I had set out from camp with a few possible routes in mind (we'd discussed Snott Girlz and Treasure of the Sierra Madres), and settled on Space Boyz in part because of its accessibility, and in part because we had climbed on the Jungle Wall already earlier in the week and felt comfortable on it. I led the first two pitches, Jake led the next two, then I led 5, he led 6, and I fell on 7. In my memory, I was about two-thirds up the pitch, about 6 or 8 feet above the last bolt with another 5 or 6 to go. It's a slabby pitch and I felt fairly secure in my footing when I reached up for the next hold. I don't remember much of the fall itself -- mostly that it happened faster than I could process and that suddenly I was hanging 20 feet below where I last remembered being sure that I had done something bad to my ankle.

What led to the fall, and why did it result in a broken ankle?

1. Inexperience - this trip was my first time leading sport climbing outside of a gym. Climbing outside is nothing like climbing in a gym. The two activities should probably have different names. Here are some of the ignorant things I thought in the minutes before the fall:

"This pitch is slabby, so it must be easier." There are 5.14s on slabby pitches, just as there are overhung 5.7s. Grade and gradient are not directly correlated. What I did learn differentiates a slabby pitch from one with greater exposure is that the risk for injury is far greater because there are more things to hit on the way down. This, I learned the hard way, is a very basic principle in climbing outdoors.

"The bolt is pretty run out here, so the climbing must get easier." Same as above -- instead of thinking, "I haven't been able to clip in a while so I'm at greater risk of a big fall," I foolishly thought, "The route setters must have known the climbing got easier here so they bolted it further apart." Being new to the route I didn't have any grounds for thinking this except that it had happened once or twice earlier on the easier pitches further down. Take nothing for granted on a route you're unfamiliar with.

"Never say take." Jake had purchased a guide to EPC written by some wanker of a Texas cowboy who finished his bullet points of advice for climbing in the canyon with those three words: Never say take, which I took to mean: keep on climbing until you finish the pitch or you're pumped and fall. There was a moment right after I'd clipped the bolt I ended up falling on when I thought "I'm pretty tired now, I should probably rest a little before finishing out the pitch. Nah, that guy said not to. I'm a macho climber. I'll power through it." Well, fuck that guy. Say take if you need to. Rest if you need to. Especially when you're new and don't know what you're doing.

2. Topography - Another important factor was that, like the 6th before it, the 7th pitch of SB goes around a corner, obscuring the climber from the belayer. It's hard enough to make a soft catch on a multi pitch fall when you can see your partner. When you can't, communication becomes all the more important, as does increased vigilance on both sides of the rope.

3. Preparation - Outdoor multi-pitch climbing is an alpine adventure, not a long day in the gym. It was a windy day and the climb moved into the shade as we went up. After two long hanging belays, I was very cold. I had brought a windbreaker, but it was in the pack with Jake for most of the climb, and it wasn't a warm enough layer to begin with and helped little once I'd got it on. Being cold for that long does a number on your muscles just like it does on your headspace. Bring layers, calories, and water, and make sure they're accessible.

Like I said above, Jake and I had set out with a couple of other routes in mind, then made a last-minute decision about what to climb. I knew nothing about the topo for SB and only had a rough idea of what the grades for each pitch were based on a quick look at Jake's guidebook. By "rough" I mean that six pitches later I misremembered the pitch I was leading as 5.8 instead of the 5.10 c/d it's listed as being. I might not have thought those ignorant thoughts I described above -- or even been willing to lead the pitch -- had I known what I was actually dealing with. Do your research when resources are available.

Outdoor multi-pitch climbing is nothing like climbing in the gym. Ease into it. Get comfortable with the technical aspects (clipping, building anchors) on easier grades where you can focus on one thing at a time. Learn about risks that exist when climbing outside which don't exist in the gym. Practise soft catches on belay. Be prepared for emergencies and all kinds of weather. And for fuck's sake, say "take" if you need to.

The trip would be a first for us in a number of ways: first big multI-pitch trip together, first climbing injury needing urgent rapping off, first time wrestling cacti for rope, first Temazcal, first night climb, the first time in Mexico and a first intention. Before flying out we decided that we not only wanted to experience this new place but also show our gratitude by giving something back. Getting in touch beforehand we were excitedly told about a program which helps kids in the area get set up to climb and the ever-present need to clean up the valley floor. So on our last day, we handed over a bag full of donated gear and then walked the El Potrero gobbling up all the trash we could find. Walking back to the camp, hours before a flight, a red truck slowed down next to us, the driver looking out across the passenger seat smiled and motioned back to his empty flat-bed and said 'Puedo llevarte esos bolsos a la ciudad por ti' - I'll take those bags to the city for you.

A big thank you to Cold Mountain Kit (CMK) for the gear donation

Photos by Jacob and text by Peter

Comments

"this trip was my first time leading sport climbing outside of a gym. Climbing outside is nothing like climbing in a gym." he says on pitch 7!!!

big alpine multipitch after only climbing indoors Grande cajones senor

to be fair I'd say potrero is a reasonable progression from the gym. That pitch is a fair bit more serious than the proceeding 6 pitches from memory. Heal well!

Great trip report - sage advice!

nice article! i want to go.