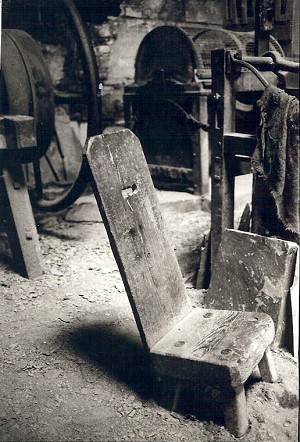

He'd kept it in the shed – in a crate underneath a woodwormed table, along with old tennis balls, a can of oil, some rusty spanners, mould-mottled carabiners and other oddments from a disorganised life. I didn't presume he'd held on to it for sentimental reasons – it had simply not been thrown away. His was a generation that never discarded things (people were another matter). I hadn't seen the straw-textured hawser rope for nearly 40 years, and, as my hands gathered in its rough texture, the memories locked in the rope's twisted strands seeped out... my Dad shouting up at me – “Not like that, you cack-handed clod!”, and my own tremulous voice imploring “I don't like it, Dad!”.

The Lakes 1971. A school Outward Bound trip. My Dad the P.E. teacher; me his disappointment of a son – eleven years-old, small, weedy, uncoordinated, scared of heights. Twenty feet up some green cliff in the Duddon Valley, on toprope, the other kids giggling as I begged to be lowered down, my Dad's disgust-filled voice entering my ears and savaging my soul: “Down?! You blooming cissy!”

Not just climbing. Swimming, gymnastics, algebra, German. A disappointment. My failings to be corrected by being thrown in at the deep end, made to vault the pommel horse, given extra homework. Psychologists would have a field day analysing why, after all the trauma, I'd later taken up climbing. Perhaps my Dad leaving us when I was 13 drove me to emulate his sporting prowess - an act of filial compensation or identification? My own amateur theory is rather different and contrarian – I believe I began climbing again years later (armed with Dad's copy of Blackshaw's 'Mountaineering'), not to identify with an absent father, but to seek something that had been sadly lacking in his vision of life: companionship, trust, security, love.

Climbers won't admit it (not without a few pints inside them anyway), but the rope-bond goes much deeper, is much more primal than the simple technical practical requirement for someone to hold the rope. “Climb when you're ready!” is code for “I'm in this with you, let's enjoy this adventure”; climbing or non-climbing. “Take in!” means “Be there for me, keep me safe”, “Nice move, Danny” is “I respect and admire you”; “Damn! You nearly had it” is “I believe in you, try again with my belief”. With my own kids I tried to ensure they always received encouragement and praise. Only my youngest showed much interest in climbing, but skateboarding and rock music ultimately won out. But, in their real lives (what climbers would call 'the unreal world beyond the rocks'), I always sought to give them a metaphorical tight rope or a helpful bit of beta, if and when they needed it.

Trust, respect, compassion, caring – none of these 'unmanly' qualities featured in my experience of my Dad. The reasons for his aporias would also detain and delight psychologists: A brutal childhood? Lack of maternal love? Who knows? Would I have been a different person if he'd been different, if he hadn't abandoned us? Again, who knows? Maybe that's one reason why we climb – rockfaces are straight up and direct compared with the crooked, winding, endlessly spiralling routes that the rest of our emotional paths follow.

Dad didn't leave for another woman. Though, to be honest, my sisters and I are not quite sure exactly why he left. It was all very scandalous, mysterious, and shame-attracting. He left his job, moved away. Rumours of alcoholism circulated. My theory – for what it's worth – is that there wasn't room in his world for anyone else. Just him and his demons fighting it out in the wrestling ring of his psyche. People were an encumbrance. Rockfaces were merely obstacles to be overcome. Whatever those demons were remained a mystery – hidden behind a stern forbidding face as daunting as the Eigerwand.

Thirty seven years after the Duddon debacle (thirty five years and a dozen or so Christmas cards and strained phone calls after he left Mum), my wife and I made the long drive to visit his home for the first and last time - to clear out the house and sort through the effects of a man who died a week ago - died almost a stranger to me (a stranger to his ex-wife, daughters and grandchildren); maybe even to himself?

Odd then that, entering the cobwebbed outpost of his garden shed, and caressing that rope, should unleash such powerful emotions in me. I felt the shame, embarrassment, unworthiness, and fear I felt all those years ago. Part of me felt the compulsion to drive up to The Lakes to revisit the primal scene. To re-climb that scruffy little route – this time dubbing my Dad's revisionist voice onto the commentary – “That's it, son, you're doing fine...I've got you”. But, as Heraclitus said, no one can step into the same river twice. If I arrived there, in the Duddon Valley, with the dusk descending, I'd be in the same space we were in back then, but the cruel thief of Time would impose its impenetrable barrier. And why waste a tank of petrol, only to end up feeling melancholy, mournful and desolate at the impossibility of restitution?

So I stayed and knelt on the shed floor, clutching the rope, recalling a Hawaiian ceremony some New Age guru had taught me once – Ho' oponopono. This involves calling up the spirit of a person whom one wishes to forgive or seek forgiveness from, mentally placing that person upon a stage, allowing your infinite love and compassion to infuse them, then symbolically cutting the rope connecting both of you. Then, if the healing is perfected, that person will return to you, and your connection will be restored. So – and this will sound bizarre – I took a Stanley knife and severed the rope that was complicit in my humiliation so long ago; the rope between father and son that had snagged and become tangled. And, at the very moment the rope was torn asunder, my ribcage was racked by a paroxysm of grief, sadness and anger. In between convulsions of sobbing, I wailed “Dad! Oh Dad! Why?”, as my wife Sandra entered to inform me that the gas and electric meters had now been read.

I'd been sceptical of the Ho' oponopono, but that night Dad re-appeared in a dream. I'd like to say he said something like 'I'm sorry, son' or 'I'm proud of you, I love you'. He didn't say anything – not in words anyway. But his face said many things. This time it was he who was frightened and vulnerable. I so wanted to reach out to him, throw him a lifeline, drag him up from the dark cold ledge where he was suffering, up to the world of light, to the safety of my belay stance. But our climb together had ended – literally and metaphorically – many moons ago. “Oh Dad, why?”

I woke, feeling agitated, and a rather bedraggled version of myself bent to pick up the mail from the mat. Among the usual bills and junk mail was a hand-written envelope. Perplexed by my recognition of the handwriting (written and sent when?), I peeled the envelope open; my fingers slithered inside and retrieved a very old faded black & white photograph. Two young, uncannily alike climbers – twins? - in woolly jumpers and tweed trousers, smiling, on some Alpine summit – hand-held coils from the rope tethering them together. On the reverse of the photograph, Dad's crabbed inscription “With my beloved brother Edward on the Rimpfischorn, that fateful day in 1949.” Like a kaleidoscope suddenly resolving into a meaningful image, the mystery of my father's life dissolved . For, just as the rope in the shed had symbolized an important invisible thread of pain in my life, another rope had defined a deep irreplaceable thread of grief in my father's.

Two ropes, three people.

Ho'oponopono. A time for healing.

Two ropes, really one, leading in an unbroken, all-embracing thread into the future.

- Who?s Who in British Climbing by Colin Wells 26 Nov, 2008

- A Review of the ?Stone Monkey? DVD 5 Apr, 2006

- Todhra by Dennis Gray 10 Nov, 2005

Comments