Wall Warriors!

A Brief History of Training for Climbing

With many thanks to Chris Hamper and Phil Kelly

Back in the 1970s Lito Tejada-Flores wrote a groundbreaking essay called 'Games Climbers Play' (later used by Ken Wilson as the title of an excellent anthology of mountaineering literature). In much the same manner as Mendeleev assigned elements to his Periodic Table, Tejada-Flores divided climbing into different 'games', such as bouldering, rock-climbing and Alpinism. Naturally Tejada-Flores had no way of knowing that bouldering would become so popular or that new forms of climbing such as DWS (Deep Water Soloing) would emerge. No matter. His taxonomy was open-ended.

Feeding the Rat

It seems to me that any climbing game can be pursued either for fun or for achievement. (Obviously one person's fun may be another's achievement - and vice versa.) Climbing for fun can massively enrich lives stressed by the demands of career and family. But who among us has not felt the insidious drive of what Joe Brown memorably termed 'feeding the rat'? Feeding the rat means achievement. It means pushing yourself. It means climbing harder.

Of Tejada-Flores' games, climbing on crags from 10 to 100 metres has proved perennially popular. So I'm largely going to deal with just this aspect of feeding the rat. For decades now, climbing harder on such crags has meant one thing above all else - training.

'If I have seen further, it is only by standing on the shoulders of giants.' Thus did Isaac Newton, a behemoth of science, acknowledge our commonality and our inevitable debts to others. Any consideration of training requires an acknowledgement of many climbers whose contributions have shown us what is possible.

I first started to climb around 1966 in a country (Ireland) with probably less than 30 active climbers. I was self-taught. Ground-up solo exploration of crumbling quarries may be slightly less dangerous than alligator wrestling but it's scarcely best practice. No matter; it was all that I had and, against all odds, I survived. Even though I didn't know any other climbers or anything about climbing, it still seemed obvious that, to be good at it, you needed finger strength and gymnastic ability. Lacking facilities such as the internet, I had no way of knowing that Pat Ament, a former gymnast, was, even then, putting up the first 5.11s in Yosemite and Boulder (e.g. the aptly named Supremacy Crack). I had no way of knowing that, several years previously, another former gymnast, John Gill, had done not only one-armed pull-ups but one-finger pull-ups. I had no way of knowing that Gill had transferred the gains to somewhere around V11 and E7. And I had no way of knowing that Gill had been inspired by stories of Hermann Buhl, an inspiration to me also.

Where Could Climbing Go?

In a Rocksport article written as the 60s tailed off into the 70s, Al Harris bemoaned that climbing was getting stuck in a rut, at somewhere around what is now top-end E2. Because many of Proctor's exploits were at Stoney, it was temptingly easy to regard his grade breakthroughs as some kind of Stoney phenomenon. And obviously there were other anomalies, such as the harder grit routes. But, by and large, top-end E2 (or about F6b/F6b+ in physical terms) represented a limit to how hard you could climb with technique, guts and crap protection. Where, Harris mused, could climbing go? One direction was extreme soloing, courtesy of Cliff Phillips, Eric Jones, Alan McHardy and the new whiz kid, Al Rouse. Rouse had gained his expertise through hundreds of hours spent crimping at his local craglet, The Breck. In retrospect, a pattern is obvious – from Haston (and those, such as Kirkus and Edwards at Helsby before him) to the Holliwells, Proctor and Rouse. But the pattern was discernible only if you could access the base information. And, with climbing media in their infancy, I couldn't.

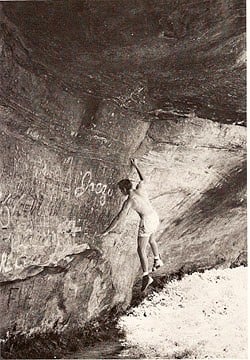

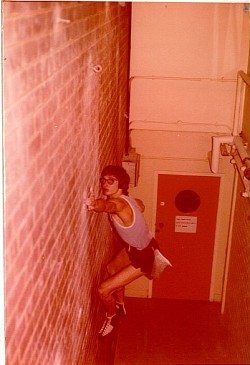

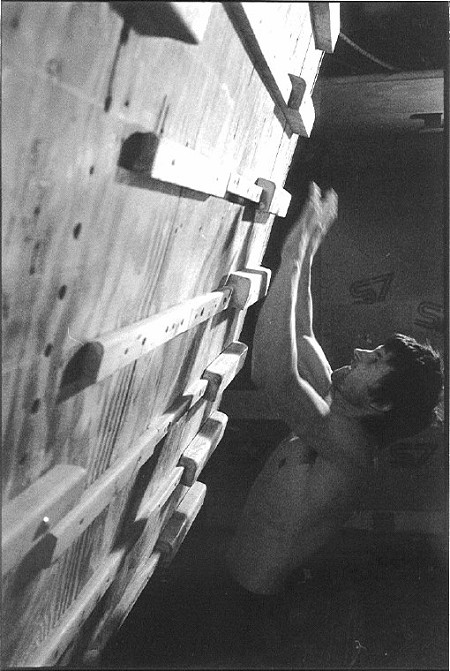

In 1964 Don Robinson had built a climbing wall in a corridor of Leeds University. Five years later, a young student named John Syrett began to train obsessively on it. Problems went upwards, downwards and sideways. Finger-wrenching traverses beckoned. The holds were polished nubbins of rock cemented into a brick wall. There were few concessions to safety and not a bouldering pad in sight. This is absolutely no criticism of Don Robinson; it's just the way things were, back then. You climbed directly above other people (the corridor was well used) and you climbed in the full knowledge that a slip might easily result in a broken skull from the floor or the opposite wall of the corridor.

How Had A Virtual Beginner Bagged the Most Feared Route on Grit?

Their Progress Was Noted By... Pete Livesey

While Syrett and his mates-cum-rivals Al Manson and Pete Kitson took Leeds wall bouldering to the nearby outcrops, raising standards dramatically, their progress was noted by a former champion runner, caver and kayaker named Pete Livesey. Previously Pete had flirted with climbing (although his Langcliffe routes may also involve flirting with death!) Now he realised that, with climbing, the athletic curve was still relatively low. Wall training could make a huge difference. It didn't matter if your wall was miles from the crags (at one time he trained in Scunthorpe), provided you put in the requisite work and applied it. And he did. Pete also had the kind of ruthless winner's mindset which, a decade later, would be honed to perfection by Jerry Moffatt. Although there was never any shortage of competition at climbing walls, it seems likely that Pete's competitive edge was rigorously focussed on projects outdoors. As Chris Hamper, one of the stars of the Leeds wall, recalls:

There was a definite shift in emphasis with the likes of Livesey, we used to play on the wall and he came to train. For us it was as much part of the sport as bouldering or lead climbing, we would have projects and get other problems so wired that we could do them one-handed with shoes on. I don't think we really saw it as training, just fun. When Livesey would visit the wall he refused to join in, preferring to traverse back and forth. We (Steve's Bancroft and Webster and me) all reckoned it was because he was crap, but thinking back it was probably

because he had a plan.

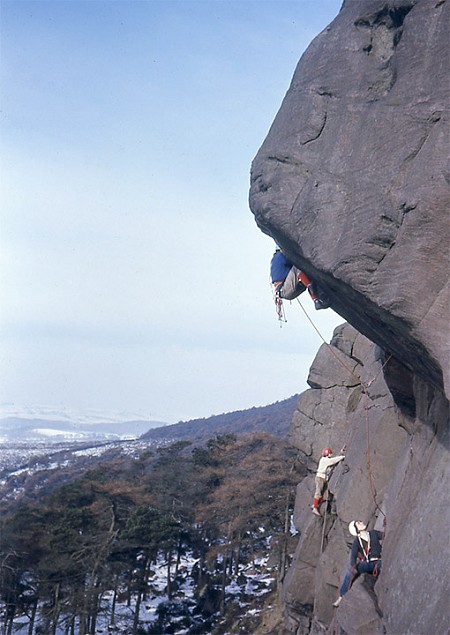

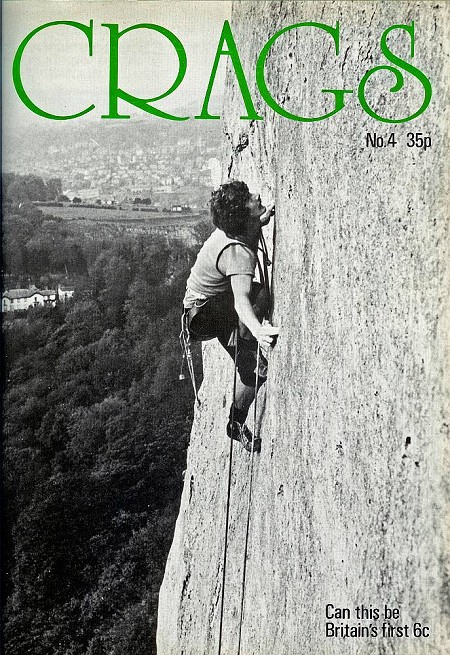

If Pete had a plan (and he probably did!), it was hugely successful. In just a few years, he raised standards from E2 to E6. British 6a, previously regarded as the living end, quickly yielded to 6b. And, crucially, Pete could climb 6b with or without protection. His protégé was a young lad called Ron Fawcett, younger, better, keen to carry on where Pete left off. Although British 6c and even 7a beckoned, interestingly John Gill's best efforts from the 1960s seem to have remained unsurpassed for a very long time indeed. Pat Ament recalls taking world-champion Patrick Edlinger to Flagstaff in the 1980s and noting that he couldn't touch Gill's hardest problems. Ament also comments that often people thought they'd done testpiece Gill problems when they hadn't; often the harder problem was a variation.

In an article for Crags magazine, Livesey distinguished between three types of climbing difficulty: the technical, the sustained and the downright scary. As the 1970s slid into the 1980s, another factor emerged: power. In the US, John Bachar was training full-time, via bouldering and his famous Bachar ladder.

The French... From F7a to F8c

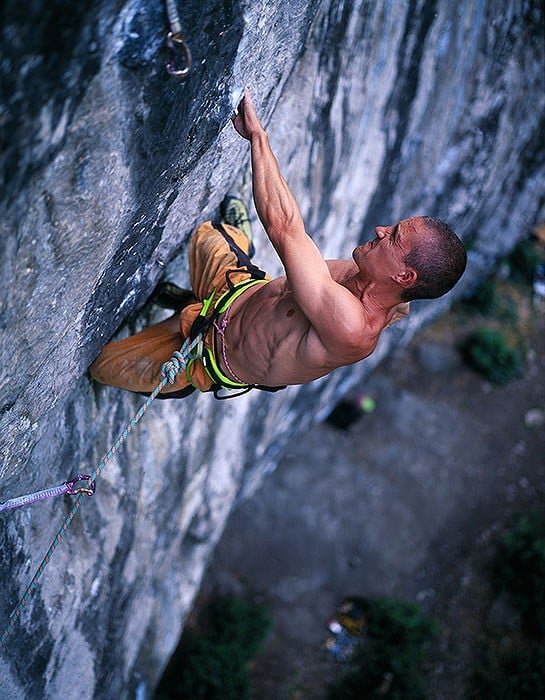

In France, generations of Fontainbleau boulderers had been supremely technically gifted. However the prevailing Alpine ethic dictated that aid (tire clous) was used to climb routes more quickly. Suddenly, in the early 1980s, everything changed. Commendably some of the first French F7a's were done ground-up with minimal protection, (e.g. skyhooks) at Cézanne's beloved Mont Sainte-Victoire. Obviously such a brave approach was self-limiting in terms of physical progress. When the French started to take free climbing seriously and applied Font expertise to their crags, F7a quickly became F8a, then F8b, then F8c. In much the same way that Livesey had learned from Syrett & co, Jerry Moffatt learned from Bachar and the French. And, as Fawcett became Livesey's protégé, Ben Moon became Moffatt's. When climbing moved from the merely vertical into the grotesquely overhanging, a new trilogy of difficulty emerged: power, power-endurance and endurance. All could be trained. The training supremo was Gullich, who took climbing to F9a with his first ascent of the world-famous Action Direct.

Perhaps the most infamous 'technology of improvement' was the fabled campus board, developed by Gullich (on a campus) to train explosive power. The iconic photo of Gill doing a one-finger pull-up was joined by the equally iconic photo of a ripped Gullich doing single finger campus moves in preparation for Action Direct.

By the mid-1990s, the training knowledge base had broadened. We knew that, if we constructed replicas of crux moves on indoor boards, specific power could be trained. We knew, courtesy of injuries to leading climbers such as Moffatt and Andy Pollitt, the truth of Gullich's sober dictum: "Anybody can get strong. The trick is to get strong and not get injured!"

By the 1990s we also knew a little more about the dangers of rogue dieting. Back in the '60s you could be a real lard-arse and still do the business, provided you had slick technique, a long neck or a raging rat in your belly. By the 1980s, lean and mean was the watchword. The prevailing dole culture of full-time climbers at places like Stoney and Llanberis rarely ran to three meals a day. But take lean and mean too far and you'll end up emaciated. You'll probably do your hardest route, only to watch your body collapse soon afterwards. How do hedgehogs make love? Carefully. Exactly the same approach applies to dieting.

Although a few people undoubtedly wrecked their bodies, in only 20 years, from the early 1970s to the early 1990s, European climbing had gone from about F6c to F9a. One reason was better protection, initially wires and cams, then bolts. Another reason was training. The 1980 television series 'Rock Athlete', featuring Ron Fawcett, was prophetically entitled. Climbers became rock athletes. Money came into climbing. The first superstars emerged with Catherine Destivelle, Lynn Hill, Patrick Edlinger and Jerry Moffatt.

From 1990 to 2010 we've gone from F9a to F9a+, maybe F9b. The huge grade advance which Livesey undoubtedly glimpsed, simply wasn't sustainable. But it's probably a mistake to view increases in standards as linear progression when they're more likely exponential. Nowadays we have a huge database of training knowledge. Nowadays we have superb leading and bouldering facilities, unimaginable to those of us struggling to find the Leeds wall 40 years ago. Nowadays children can be coached to become the champions of tomorrow. And nowadays virtually any amateur climber can dramatically improve – provided he or she goes about things in a responsible manner and avoids injury.

Our brief history of training for climbing has involved so many people. Sadly some of them are no longer with us. I'd like to pay homage to Colin Kirkus, Menlove Edwards, Don Whillans, Dougal Haston, Lawrie Holliwell, Al Harris, Tom Proctor, Al Rouse, John Syrett, Pete Livesey, Wolfgang Gullich and John Bachar. They helped to raise climbing standards. Using what they learned will help us to improve at a more modest, personal level.

© Mick Ward, 2010

Info on his ebook is at www.howtoclimbthreegradesharder.com

- IN FOCUS: Custodians of the Stone 5 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Clean Climbing: The Strength to Dream 31 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Thou Shalt Not Wreck the Place: Climbing, Ecology and Renewal 27 Sep, 2022

- ARTICLE: John Appleby - A Tribute 28 Mar, 2022

- ARTICLE: We Can't Leave Them - Climbing and Humanity 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: Staying Alive! Climbing and Risk 9 Jun, 2021

- FEATURE: The Stone Children - Cutting Edge Climbing in the 1970s 14 Jan, 2021

- ARTICLE: The Vector Generation 21 May, 2020

- OPINION: The Commoditisation of Climbing 2 Mar, 2020

- ARTICLE: 10 Things to Do at a Sport Crag 27 Aug, 2019

Comments