In memory of Jim Fullalove, Iain Edwards and Duncan Drake

1976. An Indian summer. The sun blasts out of an endlessly azure sky. I’m sitting in Manningham Park, in Bradford, talking to Jim Fullalove (Dan Boone). Both of us have climbed hard and lived harder. Unknown to us, severe tribulations lie ahead in both our lives. But, for now, the sun is shining, we’re young, we’re still relatively innocent. And on this afternoon, so very long ago, both of us are happy.

2011. Over the years, I often wondered what became of Jim. After that day in the park, I never saw him again. Of course the moment you click onto UKC and see his name, you know it’s an obituary. So he too is gone. More and more of our generation are going. Over the next few weeks, I think of Jim and some of the others, try to make sense of the complex puzzles of our lives.

It was a tough life

My father was born in 1912, my mother in 1914. Although they’re long dead, it’s sobering to reflect that, were they alive today, they’d be 102 and 100 respectively. They were born just before the outbreak of World War I, ‘The Great War’, which consumed millions of lives. When my mother was less than two years old, her father tried to break up a drunken fight at a country fair in Sligo. He was stabbed to death. My grandmother was left alone to bring up a dozen children in a grim war of independence followed by a vicious civil war. She had to deal with state-sponsored thugs and with terrorists hiding out on her land and entering her house.

It was a tough life. It was a tough life too for my father’s family. Religious (i.e. ethnic) prejudice meant that my grandfather couldn’t get a decent job to feed his dozen children. Undeterred, he mustered a few other starving men and persuaded them to open a coal mine on their barren farmland. Alas coal mining is no occupation for amateurs. One day, when my grandfather was working deep in the mine, a rock-fall triggered a mass rush for the entrance. Instead of rushing for the entrance – straight into the rock-fall, my grandfather forced the man working next to him into a ventilation shaft. The pair of them crawled up it to safety. Everyone else was killed.

It was a tough life – not just for my grandparents and parents but for tens of millions of people starving in the Great Depression of the 1930s. In World War II, sixty million people died for a freedom which we thoughtlessly enjoy today. My mother used to recall walking down Royal Avenue in Belfast and seeing body parts strewn around after the previous night’s bombing. My father worked as what we’d now term a paramedic all through the London Blitz, routinely encountering horrors which I can’t begin to imagine. My partner’s father was one of only three survivors of over 600 soldiers annihilated in a merciless fire-fight in France.

Compared with the relative affluence of today...

And then suddenly, after six terrible years, World War II was over. The first half the 20th century was almost gone. The 1950s, then the 1960s came. Compared with the relative affluence of today, nearly everybody was dirt-poor, for the price of victory was a country well-nigh bankrupted. Yet, after two world wars and a depression, at least there was peace and a slowly rising increase in living standards.

There was also the post-war baby boom, arguably the most significant demographic shift in history. Jim Fullalove was born in 1946, at the beginning of this boom; I was born in 1952, near the end of it. A generation of baby boomers grew up in the Fifties and Sixties. After two world wars and a depression, our parents desperately wanted to protect us. Their method was strict discipline. You didn’t answer back. You ‘washed your mouth out’ for foul language. You shut up and did as you were told.

‘What does not kill me makes me stronger.’

Or you didn’t. At my boarding school in Ireland, discipline was enforced with a degree of brutality which would cause national outrage today. This was as commonplace as it was well-meaning. But such coercion is both damaging and ultimately counter-productive. For the truly hard-core, of whom I was one, it proved no deterrent whatsoever. We’d never heard of Nietzche, yet we instinctively followed his celebrated dictum: ‘What does not kill me makes me stronger.’ Getting stronger proved a painful process.

The stage was set for a major, bitter and tragic conflict between our parents and ourselves. In the 1960s, if you had spirit, you rebelled. The post-war quasi-militaristic ‘command and control’ way of running things was outdated and inappropriate. We failed to see that it was also benevolent and protective; we simply reacted blindly to its repressiveness. We stuck two fingers up at it. We ran out into the seemingly eternal sunlight of the 1960s and chased three domains which, up until then, had been in remarkably short supply: sex, drugs and rock ’n roll.

The Sixties and Seventies were British climbing’s Golden Age

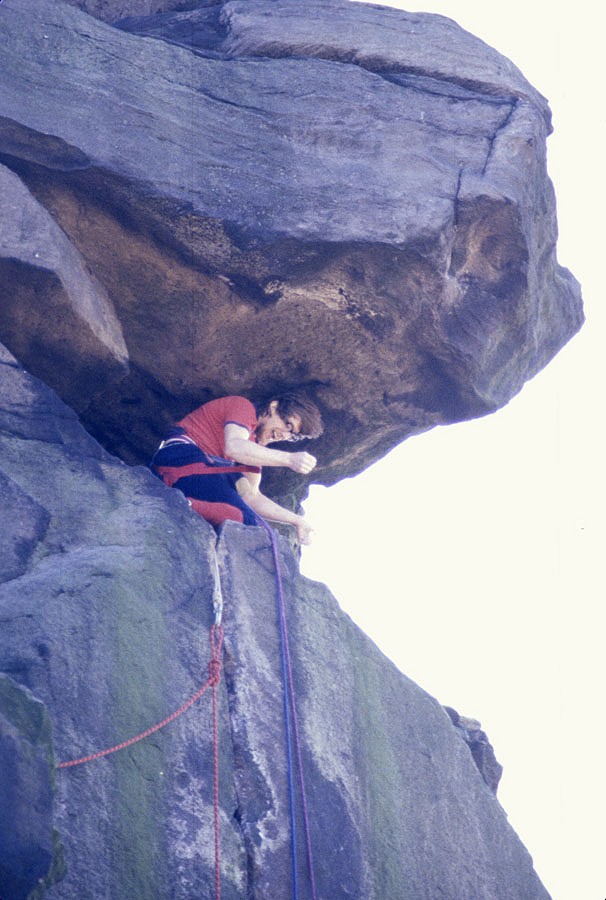

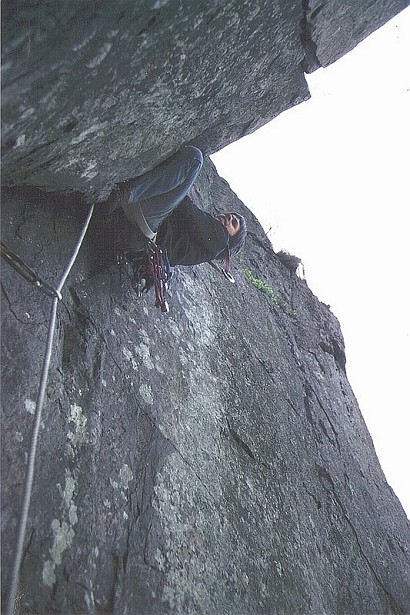

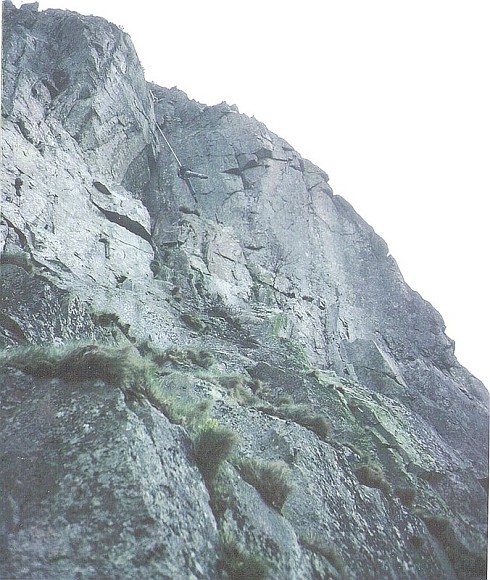

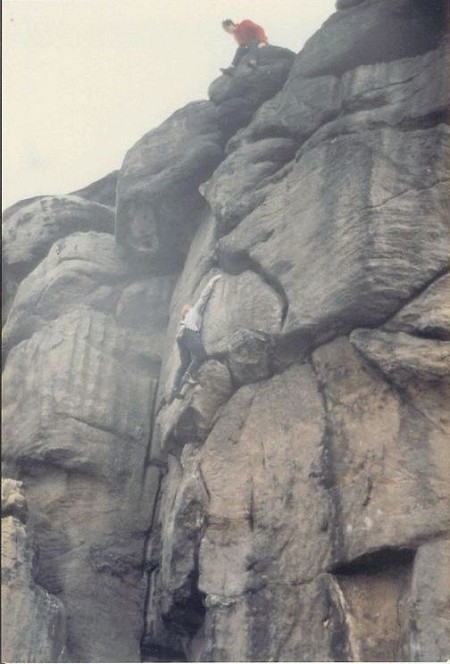

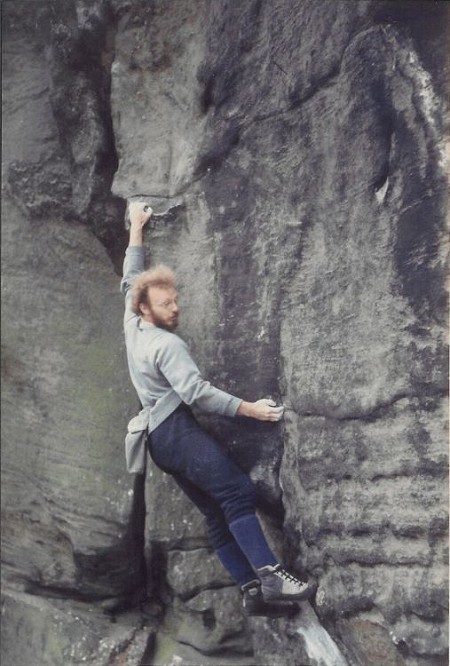

For a few of us, there was a fourth domain, climbing, which would change our lives irrevocably. The Sixties and Seventies were British climbing’s Golden Age. Major new crags such as Gogarth were discovered. Big routes, such as Great Wall, The Boldest, Right Wall and Footless Crow were done in the mountains. Many of the great lines on grit were climbed. A new athleticism sent standards soaring. VS, once the benchmark of a good climber, became trite. A top-heavy XS fractured into half a dozen E grades.

The Sixties and Seventies were also climbing’s Golden Age in America. Many of the great routes in Yosemite, Boulder and the Gunks were done or freed: Foops, The Naked Edge, Genesis, The Phoenix. 5.10, then 5.11 became commonplace. Towards the end of the Seventies, standards were pushed still higher, to 5.12, then 5.13.

(It’s vital to note that, if you missed out on climbing’s Golden Age, all isn’t lost. Most of us have a personal climbing golden age, usually between the ages of 18 and 25, before responsibilities begin to accrue. But it doesn’t really matter even if you’re as old, knackered and crap as the guy I see every morning in the shaving mirror. You can still go out this weekend, with your mates, and have your own old golden age. Do it! )

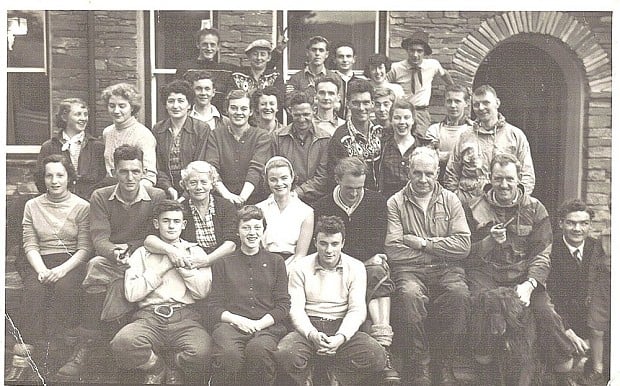

In the Seventies... there were vibrant social scenes in climbing

In the Seventies particularly, there were vibrant social scenes in climbing. Wild partying became the norm. We’d grown up with the boredom of the Fifties. We’d endured boarding schools and engineering apprenticeships in the Sixties. There was a huge pent-up surge of energy which simply exploded.

And there were drugs. After reading Doug Scott’s article about Jim, a friend noted of those far-off days, “Was it just hard-core climbers who took drugs – because I didn’t know any hard-core climbers and I barely knew anybody who took drugs?”

My feeling is that many hard-core climbers were searching – searching via climbing, via alternative lifestyles, via drugs. Today an 18-year-old climber can click onto UKC and ask a question of a 58-year-old climber. They’re both climbers – there’s a commonality – and there are 40 years of relevant experience to share. Back then, there might have been a commonality but there certainly wasn’t the same relevance of experience. When I was 18, in 1970, a 58-year-old climber would have been born in 1912 – the same year as my father. Although highly knowledgeable in some respects (two world wars and a depression), it’s unlikely that he would have understood the baby-boom demographic shift or the burgeoning youth culture which it spawned. Back then, you couldn’t ask older climbers about alternative lifestyles or drugs because they simply didn’t know anything about them. You were on your own. Or you were with your mates (who were equally clueless).

Post Mortem - the most brutal rehab imaginable

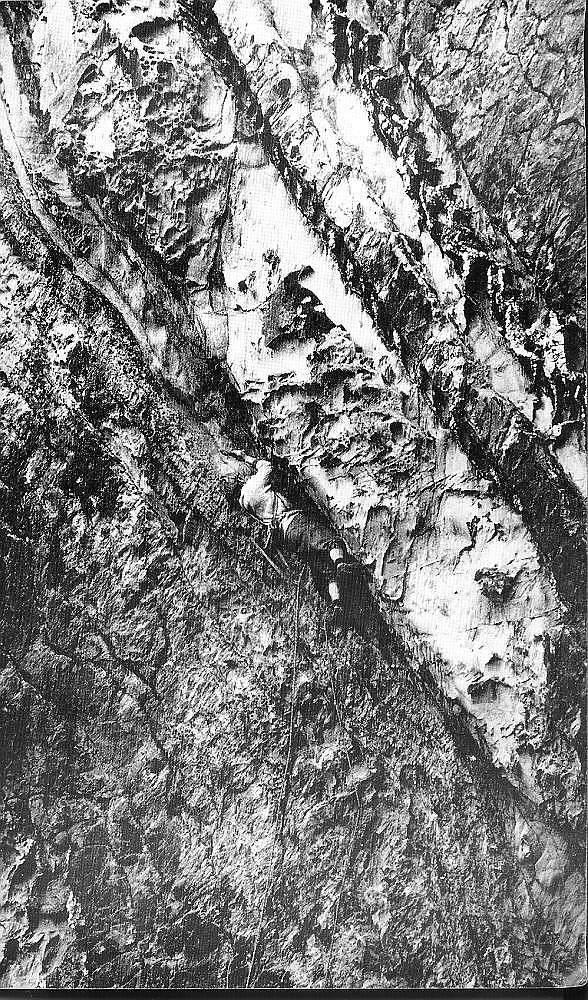

The results were predictable. We tried to force the fabled doors of perception, to break on through to the other side. Very often the doors of perception slammed shut in our faces. In 1976, after two years of generally being out of my mind, I went up to the Lakes and climbed the dire overhanging offwidth, Post Mortem, with raging cystitis (“like pissing glass”) and savage flashbacks. It was the most brutal rehab imaginable.

Wild behaviour in Cham

It would be a mistake to think that climbers in the Seventies just partied and took drugs. Activity on the crags was frenetic. Big runouts and huge falls were part of the game. There were orgies of soloing. Back in the early Sixties, ‘Das Bluejeans’ had arrived in the Alps.

By the mid-Seventies, Snell’s Field, in Chamonix, had become the European version of Camp Four in Yosemite. Wild behaviour in Cham was matched by cutting-edge alpinism, then super-alpinism in the greater ranges. Again the results were predictable: many of the best climbers of an entire generation died.

As the grim Thatcherite Eighties approached...

As the grim Thatcherite Eighties approached, the survivors of partying, drugs, soloing and scary alpinism struggled to get their lives back on track. It wasn’t easy. Too much freedom at too early an age had spawned a deep irreverence for the commonplace. We struggled to fit in. Sometimes it was just easier to stick two fingers up to the establishment, bin the job and the company car, hitch out to the grit and solo a load of Extremes.

So many lives were lost; so much talent was squandered. I never knew that Jim Fullalove had perfect pitch. I never knew that he had a photographic memory. I knew he was a bloody good rock-climber and a seriously hard-core Alpinist. Today, in more commercially aware times, these talents might have been spawned half a dozen careers.

In the end, Jim worked for the Citizens Advice Bureau in Bradford. A waste of his prodigious talents? Possibly. But my guess is that he may have found more lasting satisfaction in helping others than he ever did from climbing the Eiger.

‘Be prepared, in this way, to live happy and die happy.’

‘...the real way to get happiness is by giving out happiness to other people. Try and leave this world a little better than you found it and, when your turn comes to die, you can die happy in feeling that, at any rate, you have not wasted your time but have done your best. Be prepared, in this way, to live happy and die happy...’

I suspect that these words describe Jim’s feelings about helping other people. They certainly describe my feelings about helping other people. They were written by someone whom both of us would once have derided: Lord Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts. So has the hard-core of yore degenerated into geriatric Boy Scouts? I don’t think so... the rat still gnaws in my belly. But, after over 40 years of defiance, even the most stalwart of the ‘awkward brigade’ would probably admit that you must take wisdom where you find it.

Our time is passing...

With failing health now, our time is passing. In some ways, that’s a good thing. The baby boomers cast too large a shadow across succeeding generations. Although probably less so in climbing... The great thing about climbing is that it constantly regenerates. There’s always someone new coming along to challenge our perceptions of the possible.

You can’t live in your memories; you need to gently lay them aside and move on with your life. But, for one last time, in my mind, I’m back with Jim. Manningham Park. Bradford. 1976. It’s a golden summer. A Golden Age. And, in our relative innocence, both of us are happy.

- IN FOCUS: Custodians of the Stone 5 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Clean Climbing: The Strength to Dream 31 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Thou Shalt Not Wreck the Place: Climbing, Ecology and Renewal 27 Sep, 2022

- ARTICLE: John Appleby - A Tribute 28 Mar, 2022

- ARTICLE: We Can't Leave Them - Climbing and Humanity 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: Staying Alive! Climbing and Risk 9 Jun, 2021

- FEATURE: The Stone Children - Cutting Edge Climbing in the 1970s 14 Jan, 2021

- ARTICLE: The Vector Generation 21 May, 2020

- OPINION: The Commoditisation of Climbing 2 Mar, 2020

- ARTICLE: 10 Things to Do at a Sport Crag 27 Aug, 2019

Comments