E11 7a - First Ascent on Pavey Ark by Neil Gresham

On September 4, Neil Gresham made the first ascent of an E11 7a at Pavey Ark. Lexicon crosses briefly through the easier climbing on Impact Day (E8 6c) E8 6c, but includes an independent start and finish, making it a new, distinct line.

Lexicon is Neil's first E11. In 2001, he made the second ascent of Equilibrium (E10 7a) E10 7a, and in 2020 made the first ascent of Final Score E10 7a (UKC News).

We sent Neil some questions to find out more about his long-term 'Pavey Project'.

When did you first consider the line? How long have you been working it and what's it like?

Since moving to the Lake District seven years ago I had always wanted to check out the infamous East Gully Wall at Pavey Ark, which is the home of routes like Sixpence E6 6b and Impact Day E8 6c. It's one of those grand walls that you can't help being drawn to, being blank, overhanging and similar in character to the mighty Dove Crag, Iron Crag and the East Buttress of Scafell. I first went up there last Spring with Anna Taylor and on locating the line of Impact Day, we noticed that the blank middle section of the main headwall was unclimbed.

I abbed the line and realised at a glance that it would go, although the holds were tiny. There was a spattering of credit-card sized crimps and side-pulls, a couple of unhelpful slopers, a weird, poor undercut and a couple of half-pad 2-finger dinks. Compellingly, there was a faint groove at the top to aim for, meaning that there would be no ambiguity with route-finding. There was also an independent start up a shallow groove, which would make the line independent apart from a junction with Impact Day in the easier middle section.

The moves on the headwall turned out to be technical, fingery and unrelentingly sustained. The first section above the break felt 'hard V8' and the difficulty seemed to gradually increase, culminating with the last few moves which felt around V9. There was a satisfying flow to it all and my guess at that stage was that it was going to be an epic 8b+ power-endurance burn. But the biggest and most obvious dilemma is that there was no protection on the headwall above the horizontal break at two-thirds height. With Impact Day, there's a peg which effectively splits the headwall into two separate runouts. These runouts are big by anyone's standards and those who've taken the ride from the crux have described it as a solid 40-footer, including rope stretch. Yet with this project the fall would literally be twice the length.

I started working the line last Autumn, simultaneously with Final Score E10 7a, the new route that I ended up climbing at Iron Crag in October. I gravitated towards Final Score simply because it was easier and I felt that I had more chance of doing it. I don't say that lightly as, other than Lexicon, it's still probably the hardest trad route I've done. In those early stages, Lexicon just seemed too out-there to be a realistic prospect. I was struggling to do the last crux moves in isolation on a top-rope, so the concept of leading it was just too remote.

What training and preparation did you do?

Leading Final Score gave me a real confidence boost and I felt that I should capitalise on the momentum and turn my hand to the Pavey line while I was still in the zone. I realised I would have to raise my game further, but if I'm being honest, I wasn't daunted by this and I just couldn't wait to get involved. We all know how training is evolving so rapidly and I already felt that I had new ideas and tricks up my sleeve that I wanted to try out. The Pavey project seemed like the perfect platform, so I set about the toughest and most focused training campaign of my life.

The main themes of my training were twofold: firstly, to be ultra-diagnostic and tune things to the precise requirements of the route and secondly to take new ideas and inspiration from a spectrum of individuals, whom I respect massively. Looking at the first theme, what I mean by this is that it's very easy to look at your training needs with a filter and to do what you want to do, as opposed to what you should do. For example, for an ultra-fingery route like Lexicon it's easy to say to yourself that you just need to get stronger fingers and work on top-end power-endurance; yet on studying the route really carefully I realised that a higher priority for me was to get better at making high-steps and pushing on my feet so that I didn't need to pull as hard. Similarly, it's easy to sign up to the false prophecy that hard training will make the route feel easy. The bottom line is that if the route is truly at your limit, all training will do is give you a chance to throw your hat into the ring and ultimately, once you step in it will all come down to your ability to cope mentally. Therefore, for me, no doubt, my mental training strategies were equally, if not more important than the physical training and it was in this area where I made the most advances when preparing for Lexicon.

Regarding the second theme of getting tips and psyche boosts from others, looking back, I realised just how instrumental Stevie Haston was in coaching me to climb Freakshow, my first 8c and Dave MacLeod in helping me to climb Sabotage, my first 8c+. Sure, 95% of the ideas and effort came from me, but the key is that those guys provided me with that extra, elusive 5%. It may not sound like much, but when the margins are that slim it's what you need to tip the scales and get yourself over the finishing line. When we are failing, the project feels impossible and insurmountable and we don't realise just how close we are. When we are in these situations there are things that we just can't see and it takes someone else's perspective to illuminate the crucial missing pieces. As a coach myself, I've seen this work thousands of times, so it would be crazy for me to think that I wouldn't benefit myself.

Firstly, I went to Alex Lemel for mental training advice. Now you might wonder why a trad climber went to an insanely strong boulderer for mental training coaching – the disciplines couldn't be more opposite, right? Think again. Ultimately Alex's advice boiled down to one simple truth, which unites all styles of climbing at an elite level: "mastery". Olympic champions don't 'hope' to win, they are so confident that they can't envisage a scenario where they can possibly lose. They achieve this mindset by endless repetition and leaving no stone unturned in their preparation. Think how much prep you need to do, then treble it and then you're getting close. Of course, this doesn't mean over-training and doing endless junk-miles, it means making every second of your training campaign cost-effective and also maximising practice on your project. It meant that if I was going to climb this route, I would have to make sacrifices with my time, miss work opportunities and so on. Fortunately work was relatively quiet post-pandemic, so the planets were aligned. The take-home for me was that if I was expecting the trad climbing equivalent to an Olympic gold then I wasn't going to achieve it with the approach of a keen amateur. I would need to give everything to it.

A further kingpin for me on the central issue of mental prep was Charlie Woodburn. As one of Britain's leading trad climbers, Charlie has a fascinating perspective on the way that mental and physical training mesh together. I don't suppose you've ever had the feeling that you trained hard, filled out your training log, expected to get strong, yet for some inexplicable reason you were totally rubbish! Then, stranger still, there was that time when you got up from the couch having done hardly any training, expected to get spanked and then crushed like a hero! Welcome to the random, scatter-gun world of training for climbing, which is shared by virtually everyone. So often this leads us to lay blame on the nuances of our training plan, yet the crazy truth is that our mental health (or more specifically, the presence of underlying stress and anxiety) invariably has way more to do with our training prowess. There are neurological pathways in our brain which are keyholders when it comes to making gains in strength and endurance and if we're stressed, the brain prioritises other more pressing areas. Most of us have been feeling our share of stress since lockdown and thus I concluded, thanks to Charlie's advice, that I would put my mental health at the very top of the priority list. In the past I might have viewed some of his stress-busting tips as mumbo-jumbo, but now, to me they are of greater value for making strength gains than the minutiae of protocols for deadhanging or campusing.

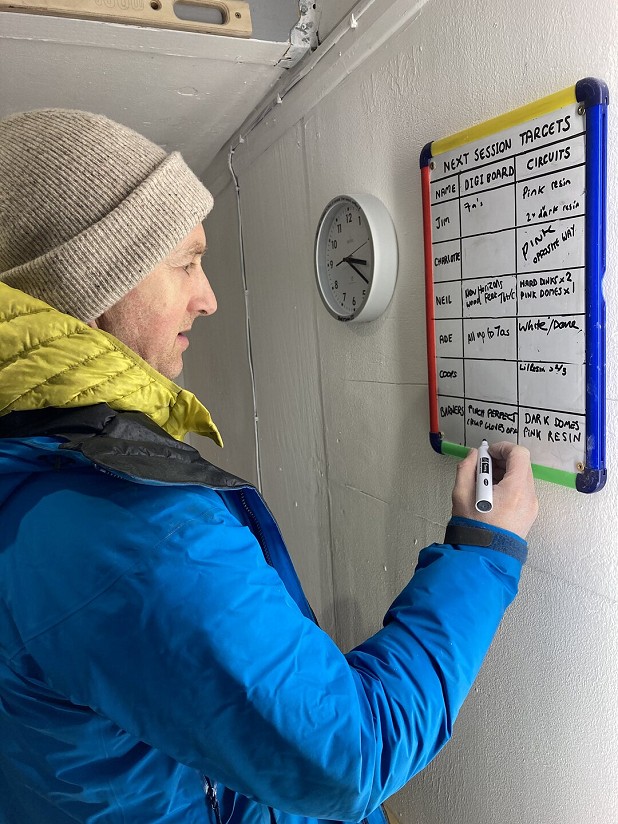

Of course, I still did all the same things that I always do to train for projects: replica boulder problems, replica circuits, training all the required grips on the hangboard and so on, but that's an accepted norm for me now. For Lexicon, it was all about adding layers to the approach, keeping an open mind and trying new things. It's so obvious that if you repeat the same training you'll get the same results, yet this is what we all tend to do, and I include myself here! The last two crux moves involve two consecutive high-step rockovers, so I decided to take lessons with ballet tutor Rosie Mackley and also to see physiotherapist Cristiano Costa for some bespoke leg-strengthening exercises. After some initial trepidation followed by a great deal of practice, I was able to stand up on footholds that were level with my chest and sure enough, this shaved sufficient margin from these moves in order to justify going for the lead.

Then there was the nutrition advice I received from Glen Burrows. I could talk forever about this, but undoubtedly it will attract controversy so I'll keep it brief and offer the usual caveats that what works for me may not work for you and that nutrition plans should be prescribed by qualified professionals. Over the last decade, under Glen's guidance I have been refining a strategy which involves manipulating macronutrient ratios in order to achieve specific effects in my training (in brief, fuelling mainly with carbs during training periods and fats during performance periods). The performance periods are NOT about dieting to lose weight – it's about being able to recover faster, control your energy levels, feel mentally sharper and (in my case at least) feel more flexible and coordinated.

The final refinement was that this time I decided to take Glen's advice about taking a 'day off' once or twice a week during the performance phase, where I was allowed to eat pretty much whatever I wanted. Glen had told me to do this many times before but I didn't really do it and made my excuses. It just feels so counterintuitive, as if you're 'dropping the ball'. After all, if you've had incredible results on a specific nutrition strategy historically then why would you come off it, if only twice a week, in the midst of a sending campaign? The answer is that just like with training - less is invariably more. By having days-off, this can help to maintain responsiveness and also, looping back to mental health, the day-off becomes symbolic with a bit of rest and headspace away from the campaign. The only problem with this advice was that it seemed to work too well and this time I took off like a rocket and hit my peak too early in August when the weather was still too warm for the send!

Finally, and perhaps most importantly of all, was the fall practice work I did on the route with my climbing partner, Adrian Nelhams. Adrian is a highly experienced Mountain Guide and coach and he was totally unfazed when I proposed to him that I wanted to take some practice lobs on the route with 'a bit of a difference'. To rewind, firstly I'd say on the whole that I'm generally fairly happy to run out the rope and take big lobs onto good gear, yet if I put my cards on the table, I'll admit that I was terrified of the runout on Lexicon. The main problem is that the headwall overhangs by about 15 degrees but the bottom wall is vertical (and up to 5 degrees overhanging in a few places). This means that the higher you fall from, the harder you will swing in and hit the bottom wall, which represents the biggest mental obstacle on the route. How would it feel to be so high above the gear knowing that if you push on further the fall is only going to be worse? Surely this would be too much of a distraction, which would sabotage my performance?

I decided to do a rucksack test. I tied in my pack and chucked it off the last move. It was a relief that it didn't hit the ground but in spite of being fairly light in weight, it still slammed in pretty hard; however, the amount it would have hurt was anyone's guess! It seemed that the only way to find out was to use myself as a crash test dummy! So with Adrian belaying, I set about a series of nail-biting fall-drills where I would lead progressively further above the top cluster of gear and then deliberately jump off and assess the outcome. The first time it didn't go well, the rope was too thick and the gear was too far off to the side. The fall was relatively short but I slammed in hard and we knew we needed to make some changes. We went for a single 8.5mm, the thinnest rope you can use with a Petzl GriGri+ and Adrian suggested altering the lengths of some of the quickdraws, repositioning one of the cams and generally re-tuning things.

Next time up, I dropped from a few moves higher, the fall was a little softer and less of a swing, which tempted me to push on further still. With all the courage I could muster, I made it to the fourth-from-last move and bailed out. I looked down to see the rope flapping and looping downwards in a huge arc and there was plenty of time to take things in as the air rushed across my face. It was the biggest whipper I've ever taken and no doubt, in spite of Adrian's best attempts to soften things, I still took a fairly hard strike, but fortunately no damage was done. The main issue is that there was no spare margin for the belayer to pay out rope in order to soften the fall, as with rope stretch factored in, you will come perilously close to the ground if you drop the last two moves. For me, the take-home from this exercise was that it was sort-of ok to fall from this point but from then on it would be best to avoid it!

Tell us about your decision to grade it E11, and the comments you've received from Steve McClure regarding the difficulty?

It was hugely beneficial to get Steve's opinion as he knows as much, if not more about grading at this level than anyone. Having had a couple of recce goes on a top-rope, his impression was that it was harder than the three E10s that he'd done recently (Choronzon and Olympiad in Pembroke and Wall of Greatness at Nesscliffe). We both agreed that it would turn out to be either a very stiff E10 or an E11, subject to how it went on the lead. Steve pointed out that no matter how strong you felt, you could still drop the last two moves as they're fairly low-percentage. The penultimate move involves driving down on a weird right-hand sloper, which your fingers sometimes 'ping' off, seemingly at random and the last move involves a dynamic lunge for a narrow 3-finger slot. It's one of those moves that requires accuracy and coordination as well as strength, so if you're slightly jittery then you'll probably fluff it!

I think if this final section was more 'secure' and strength-based then the route would be E10, but the nature of these moves is what tips the scales. Steve also described the route as 'a French grade easier than Rhapsody but with a more worrying fall'. The other thing we both agreed is that it would be a nonsense to get a gut feeling that it was E11 (based on objective comparisons with other benchmark routes that I've climbed) and then to bottle it and give it E10, just to avoid criticism. We've seen the top end of trad climbing flatline slightly as a result of this phenomenon and nowadays, grading a hard trad route is almost as frightening as climbing it! In general I'd say that standards have come on so much and that really, E10 is pretty standard now and that the question is where E11 fits in.

If you look at the breakdown of Lexicon (8b+ with 80-foot fall potential from a last move crux and the promise of a hard strike) compared to most E9s and E10s, then on paper it looks like an E11, but not compared to all of them! There are always hard anomalies at each grade, which skew things. From my perspective, I climbed Equilibrium, a benchmark E10, two decades ago and I'm in way better shape now. When I did that route my best sport grade was 8b+, but I've climbed 2 grades harder than that recently and also done all sorts of strength-based PBs, which I was nowhere near back then. I know I'm a much better climber overall, yet Lexicon still took me right to the brink and required way more preparation. I can only tell you how it felt to me and there we have it. One of my all-time heroes, Simon Nadin (the only Brit ever to win the lead World Cup series) made a hilarious Instagram post recently, where he described a phenomenon which he called 'O.M.O.S' – 'Old Man Over Grading Syndrome'. I think this appeared at a timely moment and certainly caused me to check my work.

How has your fall on Meshuga in 1999 influenced your approach to trad since? After Final Score, you wrote: 'As a father of two, hard trad feels very different to me these days.' What precautions do you take?

The fall from Meshuga only affects me in a positive way, as my judgement has improved as a result of it. I guess doing those test falls with Adrian was the main precaution, so that I could be 'eyes-wide open' about the objective dangers. These days I'm not up for doing routes with gear that can rip out (I'm crossing my fingers behind my back here with regards to Final Score). With Lexicon, I knew that the most likely outcome if I dropped the last move was that I'd sprain or break a wrist or ankle. If this happened it would end the campaign on the spot, but the outcome wouldn't have been any more serious than that. On those grounds, to me the risks were justifiable. Other than that, I just decided that I didn't want to be sketching around up there. I was either going to climb it well and in total control or not climb it. I know this is easier said than done but this is one of the main things you develop through experience. After doing all my prep, I had a pretty good idea how it was going to feel up there on that run-out and sure enough, I didn't miss a hold by a millimetre or falter even very slightly. I spent hours visualising it to prepare for every possible scenario and sure enough, it went exactly as I planned it.

Why did you pick that particular day for the send, and how did you psyche yourself up?

I think many climbers struggle to switch from endless projecting mode and it's all too easy just to keep working something because the thought of leading it is so daunting. With projects on Lakes mountain crags you just can't squander an opportunity – if conditions are optimum, you have a partner and you feel good then you have to go for it. It's that simple, because these things so rarely align. I've noticed over the years that ultimately, the ability to seize the opportunity and be a 'finisher' is the most important skill in climbing. Invariably things won't be perfect and you will have to compromise on a few areas – the burning question is how much to compromise?

With Lexicon, I could feel things escalating. A positive sign was that I did a 12-second 1-arm hang on the Beastmaker 2000 middle slot, having only managed a couple of seconds in all previous training campaigns. Of course, for a route which is predominantly a mental challenge, this provides no guarantees; but for me, it was a sure sign that I would find the moves easier and that I was ready physically. Funnily enough, it was a fraction too warm on the day but I used this to my advantage and sensed the opportunity to play one of the oldest confidence tricks in the book. On my warm-up go, I started verbalising how humid it was, how my fingers were slipping and so on, but the truth was that conditions were just-about OK. However, the act of denouncement allowed me to pull the wool over my own eyes and also gave my pals the impression that I wasn't going for it and that we could just relax into a routine, projecting day. Then I just snatched it from under my own nose before the pressure had a chance to build. There are so many cards like this, which you can play to keep the demons at bay and for me this is the most fun and rewarding part in climbing.

Why Lexicon?

I'm afraid there's nothing too deep going on here. A Lexicon is a language or dialect and I find the process of working a project to be really similar to learning a language. The moves are the vocab, you have to learn them individually and then start stringing them together before eventually becoming fluent. I guess this language is shared by all climbers who attempt projects. I think MacLeod was thinking along similar lines with Rhapsody, except with music.

British trad seems to be having a bit of a revival, probably due to people staying in the UK rather than venturing abroad. How would you describe the state of British trad at the moment? What's next for you?

I honestly haven't got a clue how to answer this. You can always rely on the '3 Big Macs' (Steve McClure, Dave MacLeod and James McHaffie) to keep pushing things, with Franco Cookson, Craig Matheson, Iain Small, Angus Kille, Jacob Cook, Hazel Findlay, Emma Twyford and Maddy Cope doing the same. Charlie Woodburn will be back too, mark my words! We have a lot of psyched, talented trad climbers here - the list is longer than you might think but no doubt it's short compared to the number of indoor climbers! The Olympics were great but I'm sure many people are ready to see what else is out there. We know how things have gone in cycles over the years and maybe trad is due a turn in the limelight. It honestly doesn't bother me as the crags and routes are still there for those who fancy the challenge and that's all that matters. All I can really tell you about is the state of me after climbing Lexicon and that is utterly and completely broken. I'm looking forward to some easier climbing and spending time with my family.

Additional thanks to Louise Gresham (for obvious reasons) and Dominic Sutcliffe of Rock On for equipment consultancy.

Neil Gresham is sponsored by La Sportiva, Petzl and Osprey Europe. He offers training plans and 1-to-1 coaching at www.neilgresham.com, and also coaches with Catalyst.