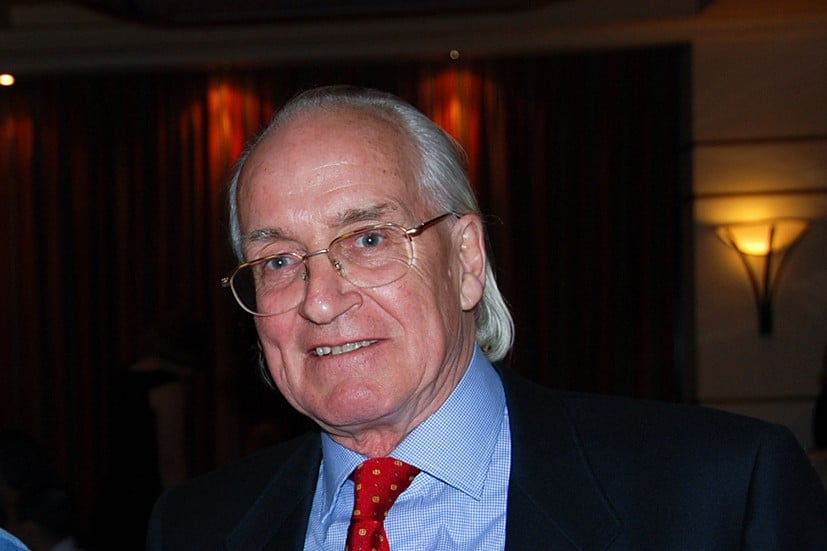

Stephen Venables remembers mountaineer, author and Community Action Nepal charity founder Doug Scott, who passed away this week.

Douglas Keith Scott (29 May 1941 – 7 December 2020)

In a career spanning six decades, Doug Scott was recognised worldwide as one of the greatest mountaineers of the postwar era. The statistics speak for themselves: over forty expeditions to Central Asia, countless first ascents all round the world, the first British ascent of Mt Everest … but what made Doug special was not the height or difficulty or number of ascents; no – for him what mattered was how you made those ascents.

Like all the best people he was a jumble of paradoxes: tough guy rugby player fascinated by Buddhist mysticism; anarchic hippy with a deep sense of tradition; intensely ambitious one day, laid back the next. He was as egotistic as any climber, but was also demonstrably generous and compassionate, admired universally for his philanthropy. In his Himalayan heyday he resembled a beefed-up version of John Lennon; in latter years, presiding over his gorgeous Cumbrian garden in moleskins and tweed jacket, he looked more like the country squire.

He grew up in Nottingham, the eldest of three brothers, and started climbing at thirteen, inspired by seeing climbers at Black Rocks when he was out walking with the Scouts. The bug took hold and he developed into a strong rock climber and alpinist. Throughout his life he would staunchly defend the British traditions of free climbing, but he was also fascinated by the aid climbing pioneers of the Eastern Alps and by Californian big wall culture. By the early seventies he was publishing regular articles in Mountain magazine, and what an inspiration they were, illustrated with his superlative photos. I remember particularly his piece 'On the Profundity Trail' describing an early, and first European, ascent of Salathé Wall with Peter Habeler. There was also an excellent series on the great Dolomite pioneers – research for his first book, 'Big Wall Climbing' – and a wonderful story of climbing sumptuous granite on Baffin Island with Dennis Hennek, Tut Braithwaite and Paul Nunn.

For an impressionable young student, dreaming of great things, this was all inspiring stuff and I lapped it up. But it was only much later, when Ken Wilson published Doug's big autobiographical picture book, 'Himalayan Climber', that I realised quite how much he had done in those early days. As well as Yosemite and Baffin Island, there were big, bold adventures to the Tibesti Mountains of Chad, to Turkey and to Kohe Bandaka, in the Afghan Hindu Kush. And closer to home there was his visionary ascent of the giant overhanging 'Scoop' of Strone Ulladale, on Harris. Now of course there is a free version. Back then, filmed in grainy black and white for television, it was a visionary demonstration of aid-climbing craftsmanship, complete with copperheads and RURPs – the art of Yosemite granite transferred to Lewisian Gneiss.

All the while, Doug had been working as a schoolteacher in Nottingham. I have no idea whether he planned all along to give up the day job and go professional, but it was Everest that made that possible. The lucky break came in the spring of 1972, with an invitation from Don Whillans and Hamish MacInnes to join them on Karl Herrligkoffer's European Expedition to the Southwest Face. The expedition failed, but in the autumn Doug was back, this time as part of Chris Bonington's first attempt on the face, defeated by the bitter post-monsoon winds. It was two years later, in India, during the first ascent of Changabang, that a message came through announcing a surprise free slot in the Everest waiting list for the autumn of 1975. With little time to prepare another Everest blockbuster, there was talk at first of a lightweight attempt on the regular South Col route, but Doug was instrumental in persuading Bonington that they should go all out for the Southwest Face. That was the great unclimbed challenge. Why repeat a well-trodden route when you could be exploring the unknown?

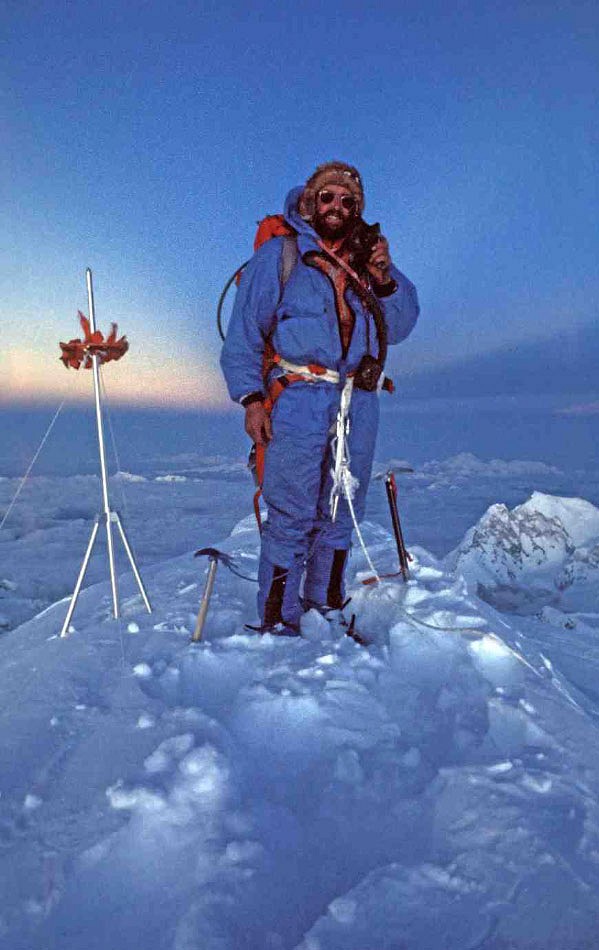

The rest, as they say, is history. I can remember the palpable excitement at the end of September 1975 when the news came through that they had done it. It seemed inevitable that Doug should have been chosen for the first summit push with Dougal Haston. In a team of big personalities, he was the biggest personality of all. Perhaps, like Hillary – who incidentally, had reached the top on Doug's twelfth birthday in 1953 – he wanted the summit more than the others; in Bonington's eyes he clearly had that extra something – that sheer bloody-minded strength, determination and ability to push the boat out.

The BBC stated in its obituary notice this week that Scott and Haston 'got into difficulties' in 1975. Complete piffle. Supremely confident, they made an informed decision to continue right to the summit, even though it was almost dark and the oxygen was nearly finished. On returning to the south summit and seeing how dangerous it would be to continue down in now pitch darkness, they agreed very sensibly to bivouac right there, higher than any other human being had ever previously spent a night, and wait for the morning. It amazes me to this day that Doug was not even wearing a down jacket, yet still managed to avoid frostbite. 'The quality of survival', as he put it, was exemplary.

Success on Everest was achieved on the tip of a beautifully constructed – and by all accounts very happy – British-Nepalese human pyramid. Even its architect, Chris Bonington, seemed at times slightly embarrassed by the sheer scale of the operation. Both he and Doug realised that the way forward lay in scaling things back down. For Doug, surviving a night in the open, without oxygen, at 8750 metres above sea level, opened a huge door of possibility. Ever curious, now he could really find out what humans might achieve at altitude.

To my mind, his finest climb was Kangchenjunga in 1979, with Peter Boardman, Joe Tasker and, initially, Georges Bettembourg. It was only the third ascent of the mountain, and the first from the north. For Doug the historian it was a vindication of prewar predictions that the North Col might be the best way to the top of the mountain. Ropes were fixed judiciously on the lower, technical face. Up above, they cut loose and went alpine style, without oxygen. Messner & Co. had already shown it was possible to climb to the highest altitudes without oxygen, but they had done it on well-known ground with other climbers around should things go wrong. This was a big step into the unknown and Doug's photos of the summit day are some of most evocative mountain images ever made.

It would take too long to list all the other Himalayan achievements, but it's worth mentioning some themes. What was impressive was the way Doug was always re-thinking expeditions. It was his idea to transfer the concept of the extended alpine summer season to the Himalaya, with loosely connected teams roaming far and wide on multiple objectives, with the family sometimes coming along too. It was he who introduced new young talent to the Himalaya, bringing Greg Child's big wall expertise to the beautiful Lobsang Spire and East Ridge of Shivling, and Stephen Sustad's stamina to the gigantic Southeast Ridge of Makalu. They didn't quite pull off their intended traverse of Makalu with Jean Afanassieff, but, my goodness, what a bold journey it was.

In fact, despite several attempts, Doug never quite summited Makalu, nor Nanga Parbat, nor K2. But that is not the point. He didn't give a damn about summits for their own sake: unless they were attained in an interesting, challenging way, they held little appeal. Or he might just decide that the omens – or the I Ching, or his particular mood that day, or whatever – were not right, as happened in 1980, when he left the slightly exasperated Boardman, Tasker and Renshaw to continue on K2 without him.

When the mood was right there was no stopping him. Amongst all the climbs I would most love to have done (and had the ability to do!), the first ascent of The Ogre in 1977 must be the most enviable: HVS and A1 rock climbing on immaculate granite, 7,000 metres above sea level, at the heart of the world's greatest mountain range – the Karakoram. Less enviable was the epic descent with two broken legs, with Chris Bonington, Mo Anthoine and Clive Rowland. Another visionary climb was the 1982 first ascent of the Southwest Face of Shishapangma, with Alex McIntyre and Roger Baxter-Jones, beautifully executed, with acclimatising first ascents of the neighbouring peaks of Nyanang Ri and Pungpa Ri, in the process scouting out a feasible descent route, before committing to Shishapangma itself, discovering the most elegant direct route to any 8,000 metre summit.

Several of my friends have been on expeditions with Doug and knew him better than I me. I only climbed with him once, when we were both speaking at an Alpine Club symposium at Plas y Brenin. We were not on until the afternoon and it was a beautiful sunny morning – far too good to be shut indoors – so we sneaked off over the Llanberis Pass for a quick jaunt up Cenotaph Corner. Doug said the first time he had done it was on his honeymoon. It was now 1989, so he must have been 48 – middle aged, but definitely still in his prime. He led with powerful ease and then suggested we continue on the upper tier of the Cromlech, up that brutal creation of his old mentor Don Whillans – Grond. In the absence of large cams to protect the initial off-width, he grabbed a large lump of ryolite, explaining cheerfully, 'This is how we used to do it, Youth,' shoved it in the crack, hitched a sling round it and clipped in the rope. As soon as he moved up the chockstone flew out of the crack, narrowly missing my head, but Doug carried on regardless – blithely calm, assured and fluent, supremely at ease with the rock.

There were other meetings, occasionally sharing a lecture platform, once having the unenviable task of having to keep Doug confined to a strict timetable dovetailing with the arrival of the Queen for an Everest anniversary. Conversation, like his lecturing – or indeed his expeditioning – could be enigmatic, discursive, elliptical, often veering off the beaten track into untrodden side valleys, but always with an undercurrent of humour. And never pulling rank: he was a humble, approachable man, happy to talk with anyone. The meeting that made the biggest impression on me was in 1987 in the village of Nyalam, in Tibet. It was the end of an expedition and we had just put a new route up Pungpa Ri, which Doug had climbed five years earlier. Also staying at the Chinese hostel were members of Doug's current team who had been attempting the Northeast Ridge of Everest.

Doug himself turned up later, just back from a gruelling road journey from Rongbuk, across the border to Nepal, then up to Sola Khumbu, then all the way back across the border to wind up the expedition in Tibet. The reason? A young Sherpa man who had been helping his expedition had been killed in an avalanche near base camp during a huge storm two weeks earlier. Doug had taken it on himself to travel all the way to the man's family in Nepal, to tell them personally what had happened and to ensure that they received financial compensation.

That empathy with the people of Nepal came to fruition in his remarkable charity, Community Action Nepal. There was a precedent in Ed Hillary's Himalayan Trust, but what I like about CAN is that it does not concentrate its efforts exclusively on the most popular region of Sola Khumbu, but also has projects in other regions such as the Buri Gandaki near Manaslu. Most impressive of all is the way Doug financed it over the last two decades. At an age when most people in his position would be happy to rest on their laurels, perhaps accepting the occasional lucrative guest appearance, Doug travelled the length and breadth of the country on gruelling lecture tours – often only just out of hospital, after yet another operation on the old Ogre injuries that had come back to haunt him – pouring all the proceeds into his charity. Lecture fees were topped up by sales of Nepalese crafts and auctions of Doug's most classic photographs. Doug the auctioneer was a force to behold, as he mesmerised and cajoled audience members into donating ever more astronomical sums for a signed photograph.

As if running a charity were not enough, Doug also managed in recent years to complete a fine history of The Ogre, and finally to publish the long-awaited autobiography for which Hodder & Stoughton first paid an advance in 1975. His history of Kangchenjunga will be published next year. For a man who had once been a bit wary of institutions, he made an enthusiastic and much liked Alpine Club President. He also stood for election to the BMC presidency, asking the journalist Steve Goodwin to help with his manifesto. Steve phoned me in despair to say that the opening paragraph was all about Doug's compost heap. Myself, I also have a profound relationship with my compost heap, and I can see exactly where Doug was coming from. But in the shiny corporate world of modern convenience climbing it wasn't going to be a vote winner. Alas, Doug did not get the presidency. A great loss to us all, in my opinion.

He was a man of principle – visionary and adventurous, but in some ways quite conservative, rooted in traditions which he valued. One of those traditions was the notion that if we climbers are going to spend our lives doing something that has no ostensible practical purpose, then it is important how we carry out that pursuit. And for Doug, if I have understood him correctly, paramount in that 'how' were notions of curiosity, personal responsibility, risk and a willingness to embrace – even seek out – uncertainty.

It is always inspiring to see someone happy in their work. Despite the frenetic pace he set himself and his devoted third wife Trish, Doug seemed in recent years to have achieved the kind of contentment that many people only dream of. He had a genuine sense of purpose and an assured legacy. He was a man who seemed at ease with himself and the world. He will be missed hugely here, in Nepal and all round the world, but most of all by Trish and by the five children of his first two marriages. I feel honoured to have known him and glad that if I should ever have grandchildren I will be able to tell them, 'I climbed Cenotaph Corner with Doug Scott'.

- ARTICLE: The Boardman Tasker Legacy 22 Sep, 2017

- The Light Elsewhere 22 Nov, 2013

Comments

In reply to Stephen,

Lovely read. Nicely written.

PS. Loved your lecture in Tiso's in Glasgow just after your Kanshung escapade.

Stephen,

As per all your books and articles this has been extremely well written with plenty of insight and interesting details.

A truly fitting account of an amazing man who led and amazing life.

Thank you. Yes, he led an enviably full life and was an inspiration to us all. Best wishes, Stephen

I thought this was a beautifully written piece and a far better tribute than any of the newspaper obituaries. Many thanks Stephen - please write more for UKC !