Mick Ward reflects on the life of Al Evans, a much-loved character of the British climbing scene and long-time highly active member of our forums, who sadly passed away last week.

Al Evans was probably the best-liked figure in the entire history of British climbing. There are many who knew him far better and for much longer than I did. This account of his life is necessarily incomplete. Hopefully it will encourage people to tell their own stories of him.

He had the ability to be a great climber. He certainly had the boldness to be a great climber. But he didn't have the selfishness to be a great climber. This isn't a slur on great climbers - but you do need to be bloody selfish. And Al wasn't."

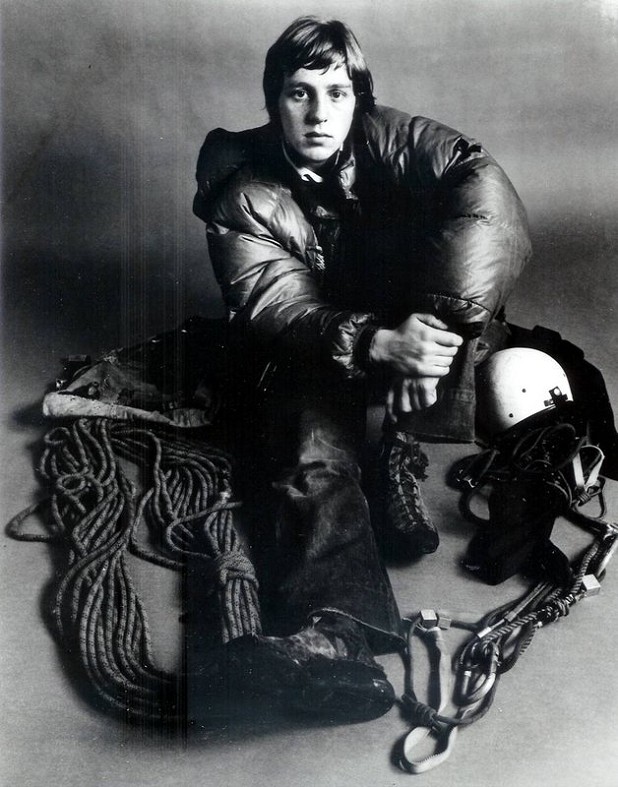

It began with Rocksport in the late 1960s. I was a silly kid, obsessed by climbing, devouring every page of it. In the new routes section, two names appeared regularly: Myhill and Evans. Who were this mysterious pair, Myhill and Evans, who seemed to be out there, all the time, making it happen? One was Keith Myhill, a very talented climber indeed, until a groundfall from the crux of Green Death effectively ended his climbing career. The other was Al Evans.

Al was born in Sheffield, in 1948. He was the archetypal northern lad, hitting the grit outcrops in the 1960s. His contemporaries were people such as Geoff Birtles, Chris Jackson and Jack Street, members of the now legendary Cioch club, based around Stoney Middleton. Nope, the name didn't indicate a longing for far-off Scottish hills. These Sheffield lads were bemused to discover that 'cioch' was the Gaelic for breast. The preoccupations of young men growing up in the vibrant sexual revolution of the 1960s...

Risqué names aside, the Cioch occupy a unique place in British climbing history. Throughout the 1950s and '60s, limestone climbing was rightly regarded as very loose and highly dangerous. A later member of the Cioch, quiet superstar Tom Proctor, would burst the bubble of convention and realise that cleaning from abseil was the way to unearth classics from beneath dodgy flakes and grubby vegetation. But the Cioch lads, with their predilection for Stoney, were almost certainly the first to embrace limestone as easily as they did grit. And they generally went ground-up. Which mean one thing - they were bold.

When the Cioch arrived in Wales, they quickly discovered that classic extremes were much less daunting than their normal Stoney fare. In 1964, when he was only sixteen, Birtles had seconded party animal Al Harris on the dreaded Thing, then 'possibly the hardest problem in the valley'. After some VSs on Stanage, baby-faced Al Evans also went to Wales and was straight into leading extremes. The upwardly mobile Birtles swiftly managed to insinuate himself into the A Team (Brown, Crew, etc). Al didn't have that kind of ambition, nor did he need it, to be accepted by the elite. He met Brown in the most prosaic of settings and they got on like the proverbial house on fire. People liked Al, they really did. You just couldn't help liking him.

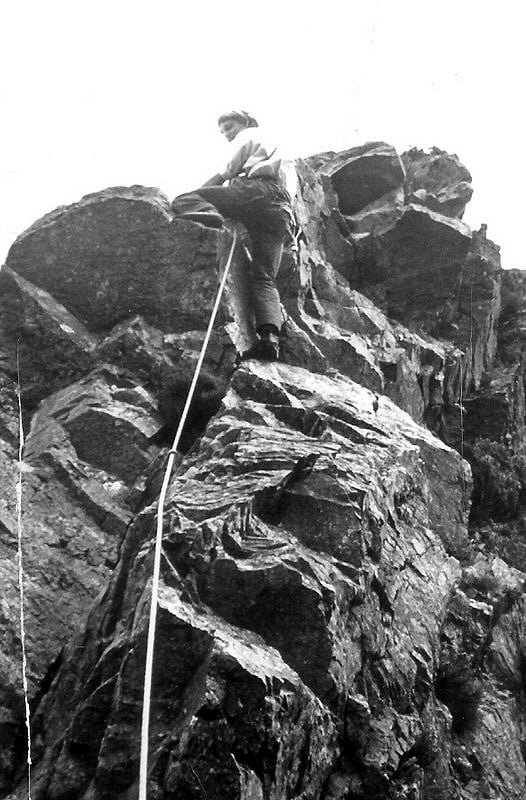

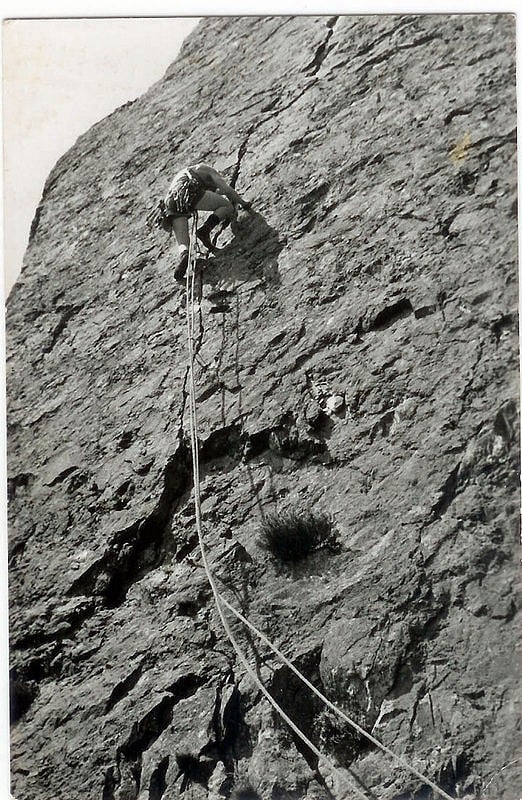

Al's climbing development was rapid, frighteningly so. Remember I said the Cioch were bold? Pretty soon Al and his mates were investigating places such as Cilan Head and St John's Head on Hoy, amongst the most terrifying crags in Britain. Horrors such as the aptly named Giant and Vulture were climbed. And it was most definitely ground-up. This was a full decade before cams were invented. Wires were in their infancy. Mostly it was good old-fashioned Moacs and pegs. If things went bad, there was no hope of a rescue. It was unbelievably bold. The St John's Head explorations paved the way for Drummond's outrageous Long Hope Route, terror raised to the level of an art form.

Once, going ground-up on the Lleyn, Al found himself stuck in the middle of nowhere, with his climbing partner. No way up. Rubbish belay; no way to abseil off. His cunning plan? Lower his climbing partner into the sea, getting him to clip a peg on another route, on the way down. Get his mate to belay him (from the sea!) then jump off, into the void, on to the peg and get lowered into the sea. I can't remember what happened, but mercifully they found an alternative. "Would you really have done it?" I demanded, decades later. Al gazed at me with those gentle eyes. "Of course," he shrugged nonchalantly.

On another ground-up first ascent in the Lleyn, approaching the top, Al realised that his layback crack was moving! Sure enough, it was the side of a flake, which was slowly detaching from the main face. Geoff Birtles and Jack Street dashed along the edge of the cliff, grabbed the top of the flake and grimly held on to it while Al continued laybacking. Experiences such as these created fiercely strong bonds of friendship. Sure, you might have your differences (the odd new route nicked, along the way) but, when it really mattered, you were there for one another.

Left to right: Pete Lomax, Mick Dewsbury, Dave Banks, Jed Storah, Gabe Regan, Nick Colton, Nadim and Rehan Siddiqui, Brian and Paul Cropper, Al Evans, Graham Hoey

Al studied photography in Preston and spent his working life with Granada television, as a cameraman and later a studio manager. Someone had to bring us Coronation Street and, sure enough, it was Al. He still did the requisite stints of kipping on Windy ledge at Stoney. Unlike some who became local specialists, he was active all over the country. In the early 1970s, on a wet day at Castle Rock, he bumped into a young lad leading The Ghost, thinking it to be 'Mild Extreme'. (The Ghost was then regarded as one of the hardest routes in the Lakes.) Al appraised the young lad of his error, realised his astounding talent and took him under his wing. The young lad was called Ron Fawcett.

In the summer of 1974, the inhabitants of the barn at Tremadog and Humphreys barn in Llanberis were poised to influence British climbing in much the same way as the Cioch had done. Two lads from Glossop were in the vanguard. Jim Moran and Al went up to Cloggy, camped there and stayed until they'd pretty much ticked the crag. (This was radical at the time; probably only Al Harris, racing up to Cloggy on his trials bike, had done as much.) Jim's mate, the legendary Gabe Regan, would also become a close friend and climbing companion of Al's.

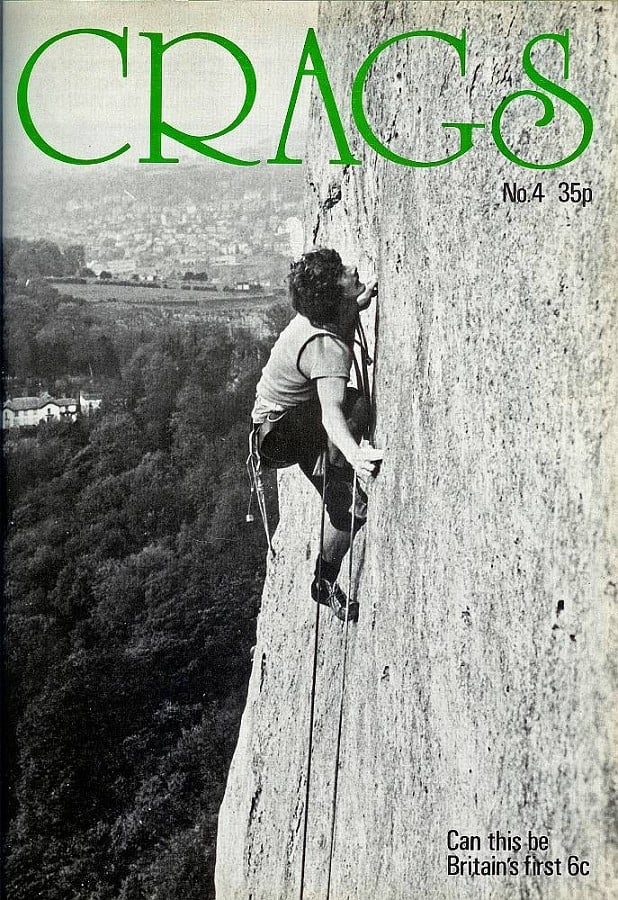

The 1970s saw a huge boom in climbing standards. With impeccable timing, Geoff Birtles captured the zeitgeist with his cult magazine, Crags. Al was the news editor, quickly finding himself reading letter, after letter, after letter about new route, after new route, after new route, by some unknown youth named Gary Gibson. Al's iconic photographs of Ron Fawcett graced the magazine. Perhaps the most fondly remembered is the famous front cover of Crags No 4. Al's photo of Big Ron on the FA of Supersonic, had Birtles' sublimely provocative caption, 'Can this be Britain's first 6c'. Clearly this wasn't the time or place for question marks! ("Me and Ron knew how to grade things (6a), Geoff knew how to sell magazines...") To add insult to injury, poor old Ian Parsons, on a nearby route, was crudely tippexed out of history; only a mysterious white blob remained, like some ghostly apparition drifting upwards. Birtles could have asked Al to doctor the photo more sensitively but hey, why stop when you're on a roll? And, back then, these boys were most definitely on a roll. The fabled Cream team: Pete Livesey, Ron Fawcett, John Allen, Steve Bancroft, and Tom Proctor, with Geoff, Al and Chris Gibb in support, were like a colossus astride British climbing.

It would have been so easy for Al to have remained merely a hero of café society. But he was happiest out on the crags, discovering new routes. Both as leader and second, he did new routes all over the country. Gogarth yielded classics such as Freebird, Aardvark and North West Passage. Yet he always said he was most proud of Jean Jeanie at Trowbarrow. (It was named after a typically bizarre incident – Al didn't really do normal - with a performing monkey.) He chose Jean Jeanie simply because it had given so many people so much pleasure. And that's really what Al was all about. He had the ability to be a great climber. He certainly had the boldness to be a great climber. But he didn't have the selfishness to be a great climber. This isn't a slur on great climbers - but you do need to be bloody selfish. And Al wasn't.

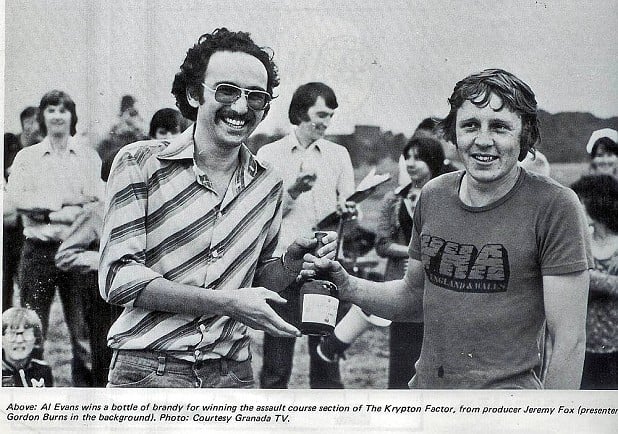

Outside climbing, Al and his protégé Ron shared a keen interest in running. Al became a highly accomplished fell runner. After filming 'The Krypton Factor', they had a 'behind the scenes' re-run of the assault course section, which he easily won. I remember him mentioning that he'd approached some Mountain Rescue teams with the idea of using mountaineers (such as himself) who were also fell runners, as a rapid first response to getting help to a victim. (This was before mobile phones and general availability of helicopter rescues in the UK.) Sadly this idea didn't find favour and Al wasn't the kind of guy to push things. But it seemed a very good idea indeed. Obviously your mountaineer/fell runners would have to be highly competent – and Al certainly was highly competent. Typically he was happy to be the guinea pig for a feasibility study. But the powers that be just weren't having any of it.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Al carried on doing what he loved doing, climbing all over the place. In 1988 he found a chance to combine his two great loves, climbing and filming, with an Army expedition to Everest. When asked (on the UKC photo database), "Did you summit, Al?" this was his reply. 'Monsooned off, on the easy slabs, 200 metres from summit.

[By radio.] "It's snowing heavily, sir." (Team lead climbers.) "Will you make it?" (Team leader.) "Think so, sir." "Will you make it back?" "Possibly." "Come back now, attempt aborted."' However galling for Al and his dead hard mates, I think we can agree that this was absolutely the correct decision. It's frighteningly easy to throw your life away in the Himalaya.

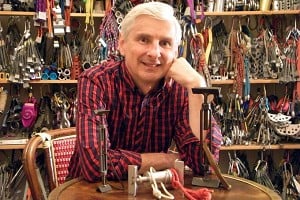

Meanwhile his career in television steadily advanced. He became a studio manager, which must have brought a horrendous level of responsibility and attendant stress. He met nearly everybody – and I do mean nearly everybody. We used to joke, 'How could you possibly claim to be famous if you didn't know Al?' Of course he didn't give a hoot whether anyone was famous or not. People are people. That's all that matters.

Once he went to Manchester United to do an interview with Denis Law. His wife, Andrea, came with him. Al wandered off (as was his wont) while Andrea waited, with increasingly impatience. Eventually a man came out and asked politely if he could help. "It's OK, I've just come with my husband to interview some footballer." "Oh yes?" the chap grinned. "Yeah, football, I mean, come on... some guys kicking a ball around a field. What's that all about?" His eyes twinkled. "Hmm, put like that, you may have a point..." Suddenly Al appeared. "Hi Al, you should have said you were coming!" "Oh hi, Denis, I've been looking all over for you!" Andrea went bright red. Denis Law just smiled gently, making light of the faux pas.

But there are good times and there are not so good times. Despite being such a highly successful professional person in a notably demanding profession, despite being such a much-loved figure in the close-knit climbing world, at times Al was troubled. And, crucially, both worlds shared a drinking culture.

Eventually the television world came to an end for Al and his department head, Jim. Jim reinvented himself as Lee Child. Al retired to the Costa Blanca. It was the early 2000s, just about the time that the Orange House started up. Al's apartment was about thirty miles up the motorway, a little way from the mainstream. In retrospect, this may have been unfortunate. Had he been closer to a merry band of like-minded companions, things might have been different.

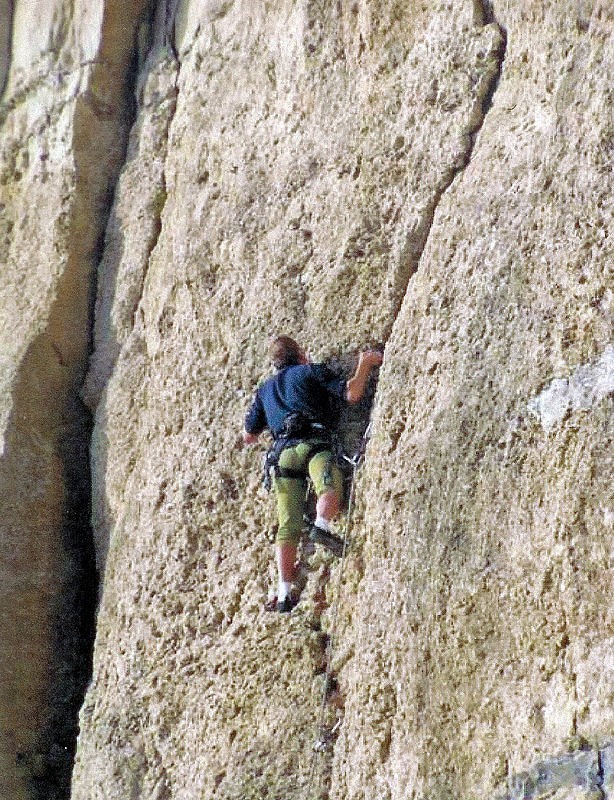

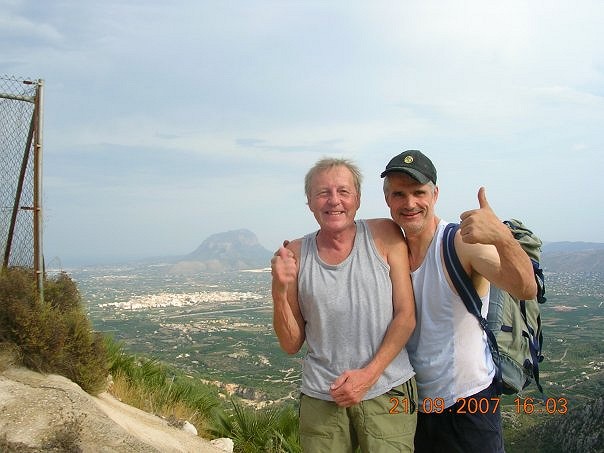

For a time though, it didn't matter. When Al arrived in Spain, he was permanently tired – probably years of gruelling television work finally catching up with him. But then he seemed to recover. He forged a climbing relationship with fellow northerner, Graham Rawcliffe, who'd lived near to him, outside Manchester. He could stand on the balcony of his apartment and look across the great ridge of Segaria with acres and acres of virgin rock, enough to keep one busy for several lifetimes.

And the first couple of years were notably busy. Al would go out with Graham, other visitors to the Costa Blanca, or just by himself, soloing. He did trad routes, ground-up. But, while I firmly believe in the peaceful coexistence of trad and sport, one might argue that the rock on the Costa Blanca doesn't really lend itself so much to trad. On Al's single excursion into bolting, he fell foul of what certainly seemed like double standards – no bolting, it's a preserved zone (but we can trash it with unrestrained building development). Similarly both Al and Graham fell foul of local council corruption. ("Give us your money – and lots of it! Out here, we make the rules.")

So unfortunately it wasn't all fun in the sun. One day Graham, fit as a butcher's dog and normally the most stoical of people, turned up at Alcalali and admitted to my partner Michèle and I that he had an acute pain in his stomach. Although I said nothing to either of them, instantly alarm bells started clanging. Graham went for tests. It was cancer. By nature, Graham was a fighter, probably as tough as Whillans in his prime, yet always an utter gentleman. He fought and fought, giving the last of his energy to an experimental treatment. But sadly he died.

Graham's death may have marked a turning point for Al. I suggested to Nick Colton, an old mate of Al's from the northern grit scene, that he go out to visit him. Nick went out with his wife, Ruth and I'm sure Al loved seeing them again. Other friends, such as Dave Parker, who'd partnered Al on new routes in the Lakes, back in the 1960s/70s, also went out. Yes, Al went through a bad phase of drinking but it seemed as if he'd got it under control. I suspect, though, that he was lonely.

But then gradually he started to withdraw. He had a friend, Michael, an Irish guy who lived in the same block of apartments. I think Michael died. Again and again I suggested meeting up but he didn't want to do so. I suspect he progressively lost confidence. Once he wrote something like, 'I don't want you to see how old I've become.' That cut me like a knife. Not that Al would have ever meant to be hurtful; he was the kindest of men. We all have to grow old. I just wanted to see him.

And then one day you find he's gone. If only I could hug him and say goodbye. But I can't.

Al was a lovely guy, he really was. He's left a huge legacy – not just all those new routes but, far more importantly, the many hundreds of people whose lives he touched.

Some years before Al moved to Spain, when he was working in television, he went out to the Costa Blanca to make a programme called, 'Sooty Comes to Benidorm'. Apparently poor old Sooty arrived and promptly fell foul of local shysters (shades of things to come, for Al and Graham). When Al was regaling me with Sooty's tribulations, we got completely carried away, much to Graham's disgust. ("Do you pair ever shut up?")

We jokingly agreed to do a new route together and call it 'Sooty Comes to Benidorm'. But typically we never got round to it. It would be a nice, wry touch to remember Al. It doesn't have to be me who does it. Feel free. (But please, make it as easy as possible, so as many people as possible can do it.) Despite his record of hard (and scary!) climbing, Al wasn't at all elitist. He was a gentle, self-effacing soul, maybe simply too good for this deeply troubled world. 'Sooty Comes to Benidorm' would be a fun, wry way of remembering him. He always had a great sense of fun. Al was a lovely guy - he really was.

- IN FOCUS: Custodians of the Stone 5 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Clean Climbing: The Strength to Dream 31 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Thou Shalt Not Wreck the Place: Climbing, Ecology and Renewal 27 Sep, 2022

- ARTICLE: John Appleby - A Tribute 28 Mar, 2022

- ARTICLE: We Can't Leave Them - Climbing and Humanity 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: Staying Alive! Climbing and Risk 9 Jun, 2021

- FEATURE: The Stone Children - Cutting Edge Climbing in the 1970s 14 Jan, 2021

- ARTICLE: The Vector Generation 21 May, 2020

- OPINION: The Commoditisation of Climbing 2 Mar, 2020

- ARTICLE: 10 Things to Do at a Sport Crag 27 Aug, 2019

Comments

Aaaaww Mick that is a really lovely article which evokes wonderful memories about Al. Sincere condolences to all of Al's family and friends. Cheers Dave

Thanks for sharing this Mick. I only know of Al Evans from reading about him, but even then he stood out as a character. I loved seeing a pic of him with Jean Horsfall and other kids climbing at Warton (https://www.ukclimbing.com/images/dbpage.php?id=113795); it made me realise how young and fearless they were when they put up a lot of those routes. I often think of that, when I'm scared on somthing! ..and that story of the monkey, I must have retold 5 or 6 times to different people...!

I probably have no right to intrude in this article but my one anecdote I realise, seems typical of the generosity of the man, as described by those who knew and loved him. I was climbing with my young teenage son around the year 2000 down at Bosigran. We had just completed Doorpost and were taking in the sun close by a far more competent crowd than ourselves. Two older guys had just finished Visions of Joanna and one of them packed up and hurried off. The other approached the crowd and did his best without success to persuade any one of them to accompany him on Suicide Wall. He then approached us and I noticed "Al" inked on his climbing shoes, instinctively I guessed it was Al Evans. "I don't suppose you fancy Suicide Wall" he asked. I laughed and admitted I had never climbed an extreme let alone one with such a reputation. He seemed to think that would add to the fun, promised to look after me and got my son's permission to borrow his dad for half an hour. Before I had time to argue, we were tied on and committed. With lots of encouragement and assistance, I joined Al on the Pedestal Stance where there was no alternative to getting up close and personal. This was my first experience of tying in to salt corroded pegs and to add to the excitement we noticed a heavy squall not too far off, I also noticed a rather fruity aroma on my partner's breath. He decided we needed to get a gallop on and scampered along the flake to the next stance below the crux. I was cajoled and pulled along to join him, and then the downpour arrived soaking us in our t-shirts and shorts. After a futile attempt to free the now soaking pitch, he without further ado climbed up me and out of sight. I was duly pulled up the crux to be assured it was effectively all over. There seemed to be a lot of sketching about for something that was in the bag and we eventually fought our way up some ferocious corner to a grateful top out. We ran back down to warm up and retrieve my boy who was asleep under a boulder. Apparently Al was acting as guardian of the Count House so he invited us in for tea and scones and could not have been more generous including making my son feel very special.

Some years later, about the time that he came out on here with some of his issues, I took the liberty of messaging him and recounting my tale. Generous once more, he recalled the occasion, correcting me as to which climb he had been on with his friend and explaining that the friend had needed to dash off to celebrate his wife's birthday but they had managed some cheeky ciders on the morning to kick off the celebrations. As you can imagine, I felt privileged to have met and climbed with such a one off. RIP Sir.

Lovely words for a lovely man. Thank you.

What an amazing time that was, what an inspiring man; what a brilliant occupation this senseless climbing can be. Thank you, Mick, you've done him justice.