To commemorate the 20th anniversary of his life-changing accident on the Totem Pole, Paul Pritchard is producing a special edition of his award-winning book The Totem Pole. He has launched a crowdfunding campaign to support the project. Paul explains:

'I walked out to Tasmania's The Totem Pole last week, as I always do on the anniversary of my traumatic brain injury. But this time it was a special 20th anniversary. To celebrate life and still being alive I am producing a 20th Anniversary Edition of The Totem Pole. To my knowledge it is still the only book to have done the double of winning the Boardman/Tasker and the Banff Grand Prize. My memoir of the events in 1998 has been taken back to the original text, with whole paragraphs that were originally edited out re-inserted. Plus there's about 40 more photos, some never seen before.'

Here is a UKC interview with Paul from 2017 in which we discuss his accident and book.

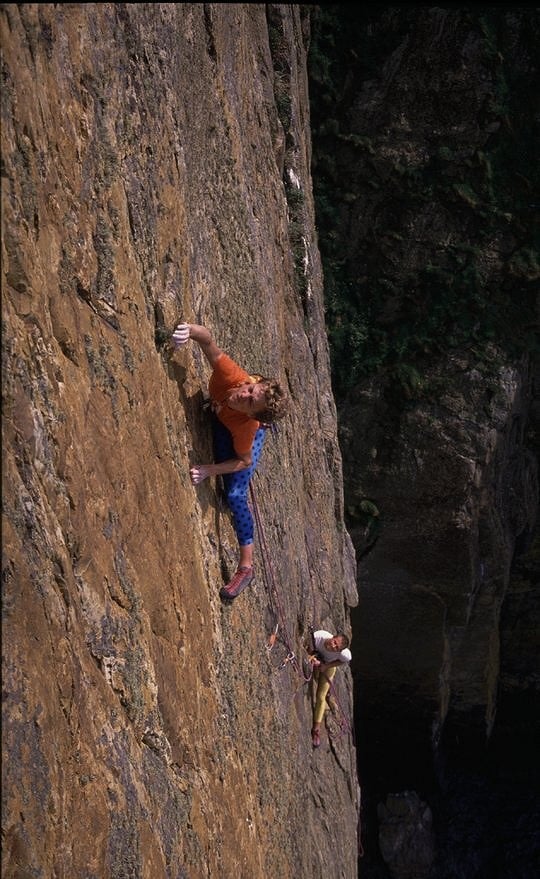

'All my climbing life I've been dedicated to the pursuit of climbing such needles. Like a hunter of pointed trophies I have ascended towers from Pakistan to Patagonia, from the Arctic to the Equator, from the Utah Desert to the Himalaya.' On Friday 13th February 1998, a traumatic, albeit ironically fortuitous event dramatically reduced British climber Paul Pritchard's physical capabilities, yet profoundly altered his perception of life and the world around him.

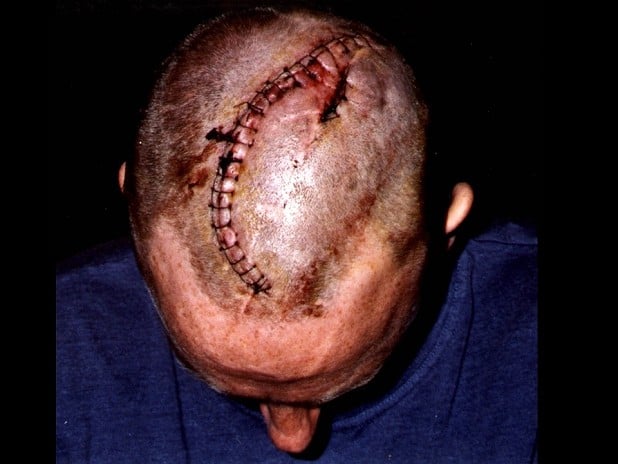

Whilst beginning an ascent of The Totem Pole - the iconic sea-stack off the coast of Tasmania - Paul's rope dislodged a block, which impacted his head and left him fighting for his life, resulting in hemiplegia - paralysis of one side of the body - as well as speech and memory difficulties. One year later, Paul returned to the scene of his accident to watch friends climb the Totem Pole, considering it to be his first and only 'pilgrimage' to the fateful tower.

Despite his physical hindrances being less than ideal for a highly-accomplished climber - with first ascents on the Torre Central del Paine and the West Face of Mount Asgard to his name - Paul's determination and positive outlook on life have seen him recover to the best of his abilities and take on new challenges - including a return to climbing.

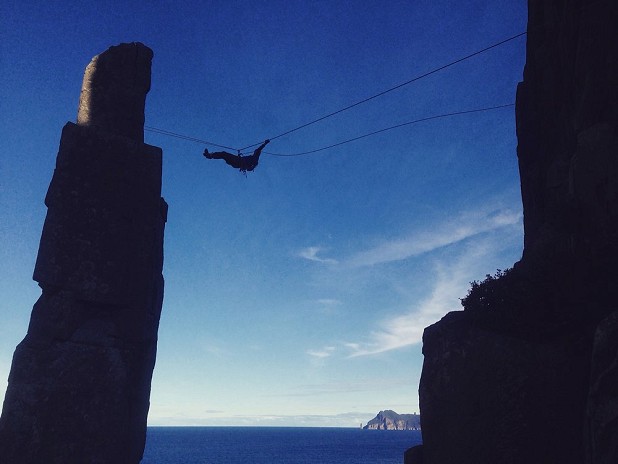

Having made an annual pilgrimage to the sea stack since moving to Tasmania in 2001, in April 2016 - 18 years since his accident - Paul went one step further and finally reached the top of the 'Tote' - bringing his new adventure full-circle and symbolically representing the 'pinnacle' of his resilience and optimism along the way. Another pointed trophy to add to his cabinet, perhaps, but surely the one which boasts the most remarkable backstory.

I asked Paul more about his incredible 'adventure' - as he puts it - spanning from the point of his accident to his recent accomplishment, using his book 'The Totem Pole and a whole new adventure' published in 1999 to chart his progression over the years.

'This is no dream, this is for real. You haven't got away so lightly. Your head is smashed in and your brain is oozing out.' - 'The Totem Pole,' 1999

'This route would captivate me.' Why did the Totem Pole have this effect on you, before even seeing the tower for the first time?

I saw this double page spread in High magazine, I think, of Steve Monks on this unbelievably thin sea stack. It was Simon Carter's famous shot of the FA of the Totem Pole. Any serious climber would give their right arm to climb it, as I did!

'All my climbing life I've been dedicated to the pursuit of climbing such needles. Like a hunter of pointed trophies.' What is it about climbing these towers in particular that attracts you?

No, it is not some deep seated Freudian obsession! I suppose it is the inaccessibility of a sea stack, a desert tower or granite spire in the Himalayas. There is no easy way round the back. This one in particular is visually stunning and terrifying. Ken Wilson told me "You couldn't find a more sexy piece of rock to have a career-ending accident on if you tried".

'You build up a relationship. You and the rock.' Before you reached the tower, what were you feeling when visualising the climb?

Same as before any climb. You, well, I anyway, gradually build up focus. There's no point in peaking your concentration too early as that will wear you out, you know - give you a sleepless night the night before. Only when I looked down from the headland and saw the Tote did I allow myself to get excited. And once connected to the rope you have to be in the moment. If your mind is off with the fairies you could have a bad accident.

The Accident - Friday 13th February 1998

'I fixed my jumar clamps onto the line and took in the slack. I cut loose in a swing off the greasy seaweed-covered boulder. I had to tuck my knees up to avoid getting my feet in the water as I flew around the arête...And that is the last thing I remember - until I came around with an unearthly groan.' - 'The Totem Pole,' 1999

Before your trip to Tasmania you had had two serious accidents previously at Gogarth and Creag Meagaidh. In your book 'The Totem Pole' you claim that these weren't 'capital letter Accidents' but that without this 'previous experience of trauma' you would have died. What did you take away from these accidents and how did you apply it to your head injury in the immediate aftermath?

Mmmm, I learned by osmosis from those accidents that I had to show extreme patience and extreme determination at the same time. Acceptance and will. All I wanted to do was go to sleep but I was certain that if I did so it would have been the last sleep I ever made. I had to stay alert and vigilant and yet remain calm and balanced also. So, I entered into a sort of meditative trance, neither asleep nor awake, neither fearful nor complacent - just non-judgmentally aware of my state and my surroundings.

'I had a moment to reflect on what seemed to be my last view: a narrow corridor of pale grey cloud flanked by two black walls, with the white foam of the sea, which was turning quickly red, right there by my head as a ceiling to my fear. I could feel the life's blood draining out of me, literally, and there was nothing I could do about it.' - 'The Totem Pole,' 1999

'It didn't occur to me then, it never had done, that I probably wouldn't go climbing again. Ever.' At what point did you begin to contemplate a life without climbing?

I spent a month in hospital in Tasmania and made good progress - I was able to sit up and grunt - apparently that is rated as good progress. I was then medivacced (never knew how to spell that!) home using eleven seats on the plane. I then spent a year in Clatterbridge Neuro-rehab on the Wirral and it was maybe halfway through my spell in there that I knew for sure this was kind of permanent. My healing curve started to flatten out.

It was during this time of depression that I sold every last piece of mountaineering equipment. I had bought a house in Llanberis and was allowed home at weekends and I remember going back to the rehab centre exhausted after a long weekend of partying. This, however, was not good for my injured brain, and much as I loved my friends in Llanberis, I resolved to move away from all this physicality.

'It felt as though I was selling fifteen years of existence down the river.' - Paul on selling his climbing gear, 'The Totem Pole', 1999

You claim that your deepest regret was causing pain to your Mother and other family members, and mention your surgeon who gave up climbing to 'do more good to people's lives than in the selfish act of climbing.' Did you consider your own climbing to be selfish at times?

Now, almost 20 years on I see that my climbing made me - instilled in me the real meaning of freedom with no past and no future, the environment provides the condition and you the climber provide the response. Climbing also taught me patience, humility and perspective and stubborn determination. Many of those traits honed through many trips to the mountains were now proving essential on that ledge with blood pumping out of my head. So, it is paradoxical to say the least, how spending time absorbed in a pastime such as climbing, which some may see as stepping out of life, can really be for the ultimate benefit of others.

Reflecting on your accident, you mention that all three of your accidents could possibly have been 'subconsciously, subliminally self-inflicted' and that you had been doing what you 'thought [you] should be doing and not what [you] really wanted to do.' Looking back now, do you know what was it exactly that you wanted to do?

Did I really say that in the Totem Pole - I have never read it you know... I knew I was grasping at some broad existential questions but for an uneducated lad from Bolton it was as if I was feeling my way along a dark corridor. Now, I see that I wasn't happy and hadn't a clue how it would ultimately end and I was scared of what life would bring but also scared of death.

Now, having died a couple of times already, death doesn't worry me anymore, so I at least attempt to make every moment count.

'You have to have faith in the brain's power to heal itself, you have to keep saying, yes I can get through this, and keep thinking positive.' You claim to have had a laid-back approach to life before your accident, but how did you maintain such a positive outlook, especially when a major part of your life - climbing - was taken away?

This goes back to my outlook garnered from the mountains as a strange amalgam of extreme patience and extreme determination. I just kept viewing this thing as the longest expedition I had ever been on.

Being a climber, how did your interest in your body's capabilities and general fitness before the accident help you to keep up your rehab?

The doctors kept telling me that it was due to my fitness that I was improving so well. Though this was after they had put me on a high protein gloop through my nasogastric tube because I was, according to the docs, so thin! But rehab as far as I am concerned is all in the head, as was climbing for me. Interestingly, I had a lot of friends who were ten times stronger than I was but they couldn't climb as well. I reckon all climbers have had that experience.

'I now have movement. Not much, admittedly, but where there's life, that activity can only get stronger. That has been my constant motto.' Paul's rehab diary, 10th July 1998, 'The Totem Pole.'

Did you notice a difference in your attitude and approach to your injury and recovery compared to fellow patients in hospital? Would you say that climbing equipped you with a certain resilience to adversity?

Acquired brain Injury (ABI) is a tricky thing. All people suffer in a different way and what it means for many people is that they lose motivation. I believe I was simply lucky to retain my motivation and my intellect. If that rock had landed an inch left or right the story could have been very different.

You mention requesting books on the brain and neuroscience from your doctors, but simultaneously throwing out old guidebooks and routemaps/drawings from your climbing life. Did this new interest in finding solutions to problems and 'training' yourself physically and mentally replace the preparation, planning and problem solving that climbing presented you?

Yes I'm sure it did. I still have a fascination with Neurology/Neuroplasticity. But it is rather interesting the parallels with climbing topos and neural networks that you point out! I have never thought about that.

Again, the longest expedition I have ever been on...

Your first time back in the Welsh hills was 'like the very first time. No. More intense.' How did returning to a place with such wild, rugged surroundings after months in hospital aid your mental and physical recovery?

My first hill was Moel Elio above Llanberis. It was a wild day and was as if I had been drowning these past 8 months and was only then coming up for air. I was alive again! However, it was intensely painful - I had no control over my knee which kept flicking back into hyper-extension. And I wasn't too far away with the fairies to consider I might never rock climb again.

'Friends would come visiting and I would strive to concentrate. Johnny Dawes came to see me and said, with a grin, "You'll just have to start climbing one-handed. I'm doing 6a one-handed now."

"How about one-handed and one-legged?" I replied.' - 'The Totem Pole,' 1999

You write about joining friends at the crag again for the first time and mention that it wasn't simply the physical act of climbing rock that you missed, but rather 'the whole event.' You mention that you 'buried such memories' and had feelings of jealousy towards other climbers: 'When I'm taken to sit in my chair below a cliff, all I feel is jealousy.' Was returning to an active climbing scene a help or hindrance to your mental recovery?

At first I considered it a complete hindrance and made plans to get out of Llanberis. However, it was on Mick Johnston's Fontainebleau stag party that I realised the love and respect all climbers have for each other (yes, even tough Lancastrian males) - I recall being on a Blackburn Coach somewhere in northern France having an epileptic seizure, and being cared for, and I recall being pushed through the sand between the boulders by my mates. Now I love going back to my old haunts.

Paul's First Return: 1 Year Later in 1999

You returned to the Totem Pole one year after your accident for a BBC documentary. Why was it important to you to return? You describe it as a 'pilgrimage to the rock that damaged [you].'

It was a pilgrimage in the sense that it was a return of spiritual significance to a place where I was reborn into a new life and new body. Without wanting to get all hippy on you, I do see it as the place where I was awakened, or at least, began my own quest (everyone has their own moment, their own quest) for the true nature of things. This I see as the fundamental search for everyone and I think one of the possible ways to realise this is through mountains, nature and a certain amount of suffering. I mean what the hell are we doing here? Surely we aren't meant to simply meander through our lives and then die...

'I felt exhilarated and excited at my imminent meeting with my 'maker' (in my present body)' - 'The Totem Pole,' 1999

Watching your friends Enga and Steve climbing on the Totem pole brought on a mix of emotions. Can you describe what you felt?

I think I wrote that it was beautiful to see what the human body was capable of. At that point, a year on, nothing could have been further from my mind than climbing that thing.

'It was seeing Enga and Steve climbing up that rock that did it, stirred in me passions for climbing that I wanted to forget about but, alas, they weren't very well buried.' - 'The Totem Pole,' 1999

You explain your reaction upon seeing the scar on the rock not with animosity, but rather it came as a 'deep shock'; 'How did that thing not kill me? I felt humbled and just happy to be alive.' Would you describe this as coming 'full-circle' with your situation?

I think I wrote that I had come full circle back in 1999, but now I have actually climbed the Totem Pole and actually made the exact same swing that almost ended my life 18 years ago. And run my fingers over the rock scar. I now am sure that it was a very fortunate coincidence, to say the least, that I am still alive now 18 years on. I now feel I can close a door on a chapter of my life. That doesn't by any means mean that I was stuck in some recurrent mental loop. No, I have been busy getting on with my life. I have spent 8 years at university getting myself an education and I have been on all kinds of adventures I wouldn't have normally entertained if I were still a single minded climber - caving, sea pedal-kayaking, white water rafting, climbing Kilimanjaro and tri-cycling to Mount Everest base camp across Tibet.

'This tower had been inextricably linked to my life for exactly a year now. There wasn't a day went by when I did not think about, analyse, dismantle or downright curse the day that I ever heard of the Totem Pole. But now I saw it for what it was, the most slender and, dare I say it, beautiful sea stack on the planet. I held no animosity towards it. How can you hold a grudge against an inanimate object? A piece of rock! For God's sake that's all it was.' - 'The Totem Pole,' 1999

In your book you describe walking along a boulder-ridden path in Tasmania, feeling as though you are climbing and are hopeful of future walks in the Himalayas. 'I fingered holds and felt edges, a subconscious habit that was proving hard to break. How I longed to climb upon them.' Since your identity had been so deeply defined by climbing, could you imagine yourself being satisfied with walks in the mountains, but potentially never climbing again?

That's a good question. I love going on long walks and rides and find that if you at least attempt to be mindful of every moment one can get almost the very same experience as when one is on a rock face. Notice I say almost: there does seem to be something unique about climbing a mountain or a rock - the slow, studied movements, the silence, or the sounds of the natural world, and of course the inherent risk. Like extreme yoga you hold a pose knowing that if you blow it you could seriously hurt yourself. So I am glad when I get back to the rock, it is like a homecoming to the mountains.

"I am my physical impairment, and my mental ones too! One's whole life experience goes to make the person. I am not saying that everybody should go out and have a catastrophic accident. But such an experience made me see that humans can endure anything. And with grace and forgiveness."

The Ascent, 18 years later, 4th April 2016

'For I knew that this would be the final time we would meet.' You wrote this sentence referring to the Totem in your book in 1999. What made you think you wouldn't return again?

Wow, did I really say that?! I guess I couldn't foresee my move to Tasmania and walking an annual pilgrimage to it since 2002. And now climbing the thing!

How have your physical abilities improved over the years?

Recovery from ABI is a slow, incremental process but the exciting thing is that you never stop improving. For example I lifted my foot (dorsiflection) for the first time in 17 years last year. Now I still cannot move my arm and still walk without a hamstring but I can walk with the aid of a stick.

When did you first attempt to get back on rock?

I think it was in 2000 I climbed 'Charity' on the Idwal Slabs with Noel Craine, and in 2010 I was dragged up the Rainbow Slab by Johnny Dawes. However, 2009 I achieved my first post accident lead climb in Arco, Italy, with Mario Manica.

You seem to have enjoyed taking up climbing again as well as other adventure sports. Tell us what you've achieved since first returning to the Pole!

Parenting my two kids has been my greatest achievement, with a three year stint as a single parent. Apart from that I have continued to lead a challenging life, climbing Kilimanjaro in 2005, caving, sea kayaking, rafting the Franklin River (one of the wildest rivers in the world) and, in 2009, lead rock climbing again. In 2011 I cycled across Tibet to Everest Base Camp. I graduated from university last year and am approximately halfway through my fourth book with the help of a AMP Tomorrow Makers grant (watch this space).

When did you first realise that returning once more to climb the Totem Pole would be possible?

I had the idea years ago of going back to the Totem Pole and jumaring up it, but never thought my arm would be strong enough to do all those one arm pull-ups (I counted one hundred and twenty-four). Then, just two or three months ago my friend, big wall climber, John Middendorf, who also lives in Tasmania, suggested a 2 to 1 pulley system might work. I had a go in his garden and it felt doable but too complicated. But the seed of an idea had been planted and I set about experimenting with different systems. I eventually settled for a simple 1 to 1 with just one leg and one arm. With a 2 to 1 you need three devices, with a 1 to 1 you need two. This system means you are pulling all your weight. So I am pulling 69 kilos with one arm (and one leg).

Did you do anything specific to prepare for the ascent?

Just jumar practice. But nothing too stressful as I have to be careful not to damage my shoulder, only having one useable arm.

Tell us a bit about the climb itself - who were you with?

I climbed the Totem Pole with Steve Monks. He was the first to climb it free in 1995 and even though he's older he is still a very graceful climber. Steve and I have a special bond over the Totem Pole: Celia Bull and I camped with him on the night before the accident. He then rappelled the climb after the accident to clean up the ropes and kit. He recalls the pool of blood he found on the ledge a day later. I then watched him climb it with American Enga Lockey for the BBC documentary, one year on. Later Steve climbed a new route on the Totem Pole naming it 'Deep Play' after my first book. Steve came down from Natimuk at the drop of a hat, with Park Ranger Zoe Wilkinson, because he's such a good mate.

Big-Wall climber John Middendorf, Margi Jenkin and Andy Kuylaars were the Sherpas and Vonner Keller was taking stills. Antarctic logistic organiser Andy Cianchi was in charge of whisky. My partner Melinda Oogjes and I slept right on the edge of the cliff the night before the climb. And Matt Newton and Catherine Pettiman were filming the whole circus for Rummin Productions.

Did climbing the tower add an extra level of closure to the accident, or were you simply enjoying it as a spectacular climb in itself?

I have certainly come full circle now. Though I don't in any sense believe this climb was my Moby Dick, I don't think I had any ghosts to lay and I don't even feel that I've finally conquered anything, like the tabloids all said.

I definitely don't climb to conquer anything. I climb because it makes me feel alive and in the moment. It is meditative in that way. Like Feldenkrais, if you know that technique, or yoga (except that if you can't make a pose you are in great danger!). And then there is the aesthetic element of the Totem Pole, it is surreal. I guess I like to conquer my fear - it's very personal. I think it was Nietzsche who said "It is not the mountain we conquer, but ourselves"...

So, yes, The climb blew me away. I mean it is ethereal in the sense that it appears so unlikely, not of this world.

You finish your book by stating that reflecting on the experience was cathartic and that you've seen things with new eyes since: 'especially the relative importance of acts such as climbing rocks, acts that I thought I would rather die than do without. For mountains and rocks don't care whether you climb them or not.' Has your attitude towards climbing changed over the past 18 years, now that you are more physically capable of climbing?

This set in motion an 18 year search for meaning. You don't come so close to death without doing some soul searching. When I say meaning, it is one's individual meaning, as everyone will come to his or her unique conclusions. Mountains and rocks are fundamental to who I am, they made me who I am. However, one must be able to take or take leave of absolutely anything and be equanimous with it.

You described observing small details on your first return to the Totem Pole that you'd neglected to notice when preparing to climb before the accident. It seemed as though focussing on the task in hand offered a much narrower perspective on life and your surroundings. As a self-confessed obsessive climber, do you think we can lose focus on the bigger picture when summits and ascents are being chased?

I think that suffering increases one's awareness, increases one's ability to be mindful, not only to your surroundings but to people and life in general. The benefits of mindfulness are now becoming discovered by scientific experiment, but they are a little ho-hum for the climber.

'The man who comes back through the door in the wall will never be quite the same as the man who went out.' Aside from your physical impairments, how did your experience change you as a person?

But I am my physical impairment, and my mental ones too! One's whole life experience goes to make the person. I am not saying that everybody should go out and have a catastrophic accident. But such an experience made me see that humans can endure anything. And with grace and forgiveness.

Also, my expressive aphasia (word finding problems) has slowed down my communication with the world. Being present has forced me to take note of the beauty, tone and character of more situations.

'They aren't suffering any more. I'm not suffering any more. We have had our lives altered. We are just different.' - on hemiplegics, 'The Totem Pole,' 1999

"Disabled not unable" is your Twitter tagline. What advice would you give someone struggling with a disability - hidden or visible?

You have to learn to accept their situation, or suffering will be the outcome. Let the future go without anticipation. With acceptance comes the courage to navigate the necessary stumbling stones of life. Also, you don't have to win, or even come close, to succeed. You just have to be the best you can - that goes for everyone.

What's next for you?

This September myself, a legally blind friend, Duncan Meerding, paraplegic Dan Kojta and Walter Van Praag with 38% lung function (due to Cystic fibrosis) are going to attempt to cycle from the lowest point in altitude to the highest point in Australia. The 2100km ride from the middle of Kati Chanda (Lake Eyre -15m) to Mount Koscuiszko (2228m) has never been attempted before, even by the fully able, and much of it will be across bare desert.

Watch some footage of Paul climbing the Totem Pole below:

Watch a video of Paul talking about his recovery and climbing Rainbow Slab with Johnny Dawes:

Watch a video of Paul's recumbent trike 'pilgrimage' to Mount Everest:

- SKILLS: Top Tips for Learning to Sport Climb Outdoors 22 Apr

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

Comments