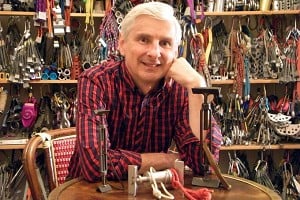

Two chapter extracts from former Rock and Ice editor Francis Sanzaro's latest book, The Zen of Climbing, which places the climber's mind at the forefront of training and practice.

Is Climbing a Zen Sport?

Zen isn't about being relaxed, it's about being poised.

In 2002, a watershed paper was published in the Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. The paper was titled "Psychological Characteristics and Their Development in Olympic Champions." Subsequent studies have further refined the findings, but what they discovered in 2002 remains as true today as it did for ancient Stoics, Zen samurai, 9a+ climbers, and, of course, Olympic athletes.

In the paper, the trio of researchers found the following attributes to be shared among medalled Olympic athletes: "(a) the ability to cope with and control anxiety; (b) confidence; (c) mental toughness/resiliency; (d) sport intelligence; (e) the ability to focus and block out distractions; (f) competitiveness; (g) a hard-work ethic; (h) the ability to set and achieve goals; (i) coachability; (j) high levels of dispositional hope; (k) optimism; and (l) adaptive perfectionism."

The list is a roadmap for athletic excellence. But maps are often deceiving. Though the researchers never mentioned Zen and were mainly interested in listing the mental traits of Olympic champions, it begs the question—can I get some of that? I didn't discover the paper until I had a good draft of this book, but when I did read it, I had a lightbulb moment: I was writing about all of these things, not just listing them, but about how to cultivate them on a deep level in our bodies.

My conclusion: Zen can help all athletes improve on every aspect of the above list. Yes, every aspect.

As regards anxiety—defined as the experience of failure in advance—it is possible to get to a place where your focus is so attuned to execution that single-minded attention becomes the goal rather than an outcome. When that happens, failure is redefined in your climbing as the quality of experience as opposed to the quality of goal. Distractions lose their power and constriction on performance. Zen martial artists call them "blockages."

As regards resiliency, you can develop fluidity of mind such that you can toggle in your climbing, a mental spontaneity allowing the mind to come "in and out" across your body, as needed, with varying intensity and precision. You recover from panic quicker, relax faster and know how to apply mind in varying degrees, whether on a WI6 smear, V8 or 5.12b/7bX big wall. Having a Zen mind doesn't mean you are relaxed and aloof—quite the opposite. It means you are poised and ready to apply whatever mind you need. It means you understand what mind is, because it doesn't mean what you think it does.

In terms of confidence … well, you will learn that confidence is one of the most overrated mental components in top performers.

As for intelligence, you will learn to rely more on natural, or somatic, intelligence. You will learn to train your body to make intelligent decisions on its own, bypassing the cumbersome machinery of calculation thinking.

As regards competitiveness, Yagyu Munenori, a 16th-century swordsman and Zen master, says it best: "It is an illness to think solely of winning." As I learned, the main thing holding you back is the you that wants. The desire to win and the ability to perform your best are almost always mutually incompatible. Why is that? Strong desire creates destructive patterns of anticipation, misaligned expectation, feelings of failure and a vacillating sense of self-worth hitched to improper definitions of success.

Understanding Zen as it relates to climbing will not make you an Olympian, but it will change the way you climb. For the better. Climbing is moving Zen, but the simplicity of the statement—to make climbing a Zen practice—masks the complexity of the task and threatens to tokenise climbing as a romantic warrior enterprise of self-improvement (which it isn't) and leverage Zen for the goal of climbing harder. Both would be unfortunate outcomes, but both are avoidable. We can avoid them by not taking shortcuts. By going deep. By acknowledging the complexity of our inner world and the complexities all athletes experience.

All climbers need to improve in a few of these aspects:

~ climbing without fear (of falling, or failing)

~ not getting fixated

~ removing sources of frustration, fear, anger, self-loathing

~ fully integrating bodily movements and mind

~ spreading the mind equally into the body's limbs

~ concentrating mind on an appendage with rapidity

~ moving without blockages

~ cultivating spontaneous action with mastery

~ removing ego-thought from intelligent action

~ listening deeply to the language of stone and body

~ removing all unnecessary baggage, such as self-importance

Each of the above is relevant to elite and beginner climbers, alpinists, boulderers, ice climbers. Each of the above is relevant to boxers, rugby players, runners, MMA fighters…in short, all athletes

Of course, continue to do your hangboard repeaters and train with all the new gadgets and protocols. Campus, work your weaknesses, stretch. Rest the right amount. Get a coach. Diversify the types of climbing you do. The space I'm trying to carve out, however, is upstream of physical training and most "tips to improve your mental game" literature, which is notoriously shallow and composed from the mentality of inevitable failure. What I'm talking about is a full-on reevaluation of how you approach the sport, a reevaluation that will help you fully embody, and discover for yourself, what sports movement researchers describe when they talk about the importance of variability, creating biomechanical advantage, using momentum, calibrating motor control, learning when to employ contralateral movement, cultivating the performance mindset, and so on.

We are going to go to the source: mental acuity is the fastest way to train physical acuity. Being strong does not translate into better technique, or a smoother mind-body interface, but a sharp mind will flow down to more controlled movements, increased spontaneity and decreased frustration. You can buy the best shovel, but if you don't know how to dig, you won't get very far.

***

Routes. Moves.

A route takes on a gravity in our minds, but movement is weightless.

For a long time, I thought a route or boulder problem was the thing I was looking at. Or trying. Or falling on. It had a beginning and an end. Between that beginning and end was try-hard. The idea was to put in a good effort and send it. That's the goal. Get the goal and feel good, then set a new goal. Get better. Feel better that I'm getting better. Do this until I get too old to climb hard, then figure out a new plan. Most climbers think like this, yet it's a flawed way of thinking. It is small-mind thinking, and therefore a small experience. We are making ourselves, and our effort, instrumental. We are pimping ourselves out for something other than climbing. The essence of small mind is when it is related to something outside itself. Mind, in its essential nature, contains everything, and is therefore deformed when fixated. We see our own deformation in the way we approach routes.

A route or problem is an athletic performance— that performance is the sum of moves over a duration of time. Those moves are often broken up into sections. You try to climb to the "rest," and then there's a punchy section, then a final crux. In alpine or trad climbing, it's broken up into pitches or big features. Climbers discriminate and partition these moves, but in reality, a wall is unbroken, just as in nature there's no such thing as the border between Russia and Poland. It's a construct, not a physical border. A concept. That's obvious, but what is important is that insofar as borders are artificial, so too is movement. We never stop moving. Climbing is just a different form of movement. Movement never stops. Athletics is a ritualised movement, in a ritualised place, which we all agree to enter based on certain stipulations, boundaries and cultural agreements. Meanwhile, despite our attempts to control it, life thrusts itself in, through, and around us at all times. Change accompanies us at every turn. Taoism, of which Buddhism has become philosophical friends for centuries, speaks of chi energy as being in a natural state of ceaseless flow, and only when it stops does it lose its properties. A Taoist monk's goal is to chase the flow as it moves, not arrest it. Zen has little tolerance for talk of mystical energy, but the base understanding as it relates to climbing is the same: it is only when we think holistically can climbing movement, or any act, get the proper respect it deserves. Why respect, you might ask? That we have to ask that question is indicative of our ignorance.

It's natural that the complexity of climbing movement occludes a simple approach. Each move we do is an articulation of our limbs in coordination with our will, neural patterns, muscle memory, and complexified by our emotions. The analytic pit may seem bottomless, and overthinking is to be expected, but returning to the beginning, what often holds climbers back is the sheer presence of a route. The weight of it on their psyches. In other words, in considering the route, even before we have climbed on it, we invite a trojan horse into our mind. We do this with everything, however, with careers, money, status: outside of the values we attribute to them, they are meaningless. Life is value agnostic. Nietzsche, the great German thinker, was right on this point.

When we value things, we become attached to them, which invites anticipation, anxiety, desire, expectation, failure, self and, eventually, ego, but also, of course, elation, happiness, accomplishment … all of which are perfectly normal, until you realise the trojan horse isn't doing you any good. Yet, a funny thing happens when you stop fetishising the route—you just start doing moves. After much practice of just doing moves, you like climbing more, and you like it more often—and develop a deep sense of the craft of climbing. Here you get a glimpse of the eye of the shokunin. A radical form of embracing the process. Process is time without a goal: a hard unknown, not a soft unknown. Process is moment. Because your body is riveted in time, if we follow the cue of yoga, when we yoke ourselves to our spatio-temporal anchor, which is what a body really is, we, by a twist of mechanics, create the space for small mind to unmoor itself from distraction.

Jonathan Siegrist, one of the top sport climbers in the US, reiterates this near-universal formula for athletes wanting to do their best: "I think climbing 75 your best is largely about quieting your mind enough to let your body do the work it's been trained to do. I pride myself on being somewhat of a master in this realm but there have also been times when it feels next to impossible. Ultimately, I only succeed when my focus is on the rock, the movement and the effort—and not on the outcome, consequences or my expectations."

As Irena Martinkova and Jim Parry put it in an article on Zen and sports, when movements are an end, rather than a means, our moves, and the athlete, become "instrumental." When that happens, quality degrades: A tennis player, for instance, only plays well enough to beat their opponent, or a climber climbs just well enough to get up a 5.9/5c when they are a 5.12a/7a+ climber (small experience). Both scenarios are unfortunate, not to mention missed opportunities for further perfecting the craft, since it would be wholly untrue to claim there's nothing to learn about climbing, and ourselves, when we are on easy terrain.

Since climbing is about routes and boulders and mountains, and routes are about moves, and moves are a body-in-performance, and performance is an experience, it follows that if you change the experience by removing the concept of the thing you are trying to achieve, you change your perception of the stone, and, with it, the nature of the climbing experience. It does not mean you have lost the fire to improve, only that improvement is redefined. You start to learn.

Sanzaro is a former Editor-in-Chief of Rock and Ice and author of the classic The Boulder: A Philosophy of Bouldering.

Buy the book here.

- The 9A Future of Bouldering - Beyond Style 18 Feb, 2015

Comments

It just so happens that I finished reading this book on the plane home from Kalymnos yesterday. It is absolutely excellent. Indeed, it may be the single most insightful book about climbing ever written - reading it and beginning the (life-long) effort of internalising what it has to teach may be the single best thing any climber could do. Seriously.

I'm glad you posted this glowing review. I read the excerpt, got inspired, bought a copy, then worried it was going to be a load of new age tosh. Looking forward to reading the full thing now!

In terms of confidence … well, you will learn that confidence is one of the most overrated mental components in top performers.

Confidence in movement is very important however

Anyone else struggling to buy this book using the link in the article? It adds to basket, but every time I hit checkout it just jumps back to the website homepage.

Yeah that was my big worry too - but it is absolutely a new-age-bollocks free zone.