As we reflect on an eventful IFSC World Championships in Bern, Switzerland, John Burgman tells the story of the country's unsung competition climbing heroine. Swiss climber and two-time world champion Susi Good ruled the competition scene in the early 1990s…then she suddenly walked away. What happened?

In order to understand what Switzerland's Susi Good meant to competition climbing—and how her brief career was ultimately so impactful—it pays to peruse the results of the earliest World Cups.

As a fully-fledged circuit, the World Cups began in 1989, and while Britain's Jerry Moffatt and the USA's Robyn Erbesfield won the first-ever World Cup event, the country that ruled the scene was France.

In that first year of competition, more than half of the women who earned spots on World Cup podiums were French. That ratio stayed roughly the same the following year. In one particularly dominant stretch in 1990, a French woman won a gold medal at four World Cups in a row. And the first-ever "country sweep" of a podium occurred in Lyon, France, in 1990, when three French men claimed all the medals.

There were occasional standouts in both the men's and the women's divisions from other countries, but more often than not, the competitors garnering the headlines were Nanette Raybaud, Catherine Destivelle, Isabelle Patissier, Didier Raboutou, François Legrand, François Petit, Jacky Godoffe, J.B. Tribout, Robert Cortijo, and François Lombard—all from France.

Such French supremacy underscores why Susi Good was a disrupter of the status quo when she burst onto the scene and eventually started winning consistently. Good helped usher in a global era of competition climbing, a scene in which any athlete from any country could become a star.

Conversely, Good's climbing career didn't start with ambitions of being part of a pioneering global squad or winning eventual World Championships or even being a competitor at all. She started climbing in 1983 with her boyfriend (and now husband) Edwin, the two of them tasked with exploring routes that had been bolted by a friend in their hometown of Mels, Switzerland.

The routes were not particularly difficult, but for Good—who had grown up in a family of hikers, not climbers—the climbing presented newfound physicality that was instantly captivating. In particular, Good liked pushing through the fatigue, and in doing so she discovered her talent. "I liked having new challenges all the time, and I loved it when I got really tired arms," she reflects today at the age of 57, 40 years after pumping out on those formative routes in Mels.

Talent blossomed in the years that followed, as Good and her boyfriend travelled around Europe for more climbing. On one such trip—in France, no less—Good was approached by Wolfgang Kraus, an accomplished German climber who coached some German competitors. Kraus noticed Good's talent and suggested that she take part in competitions. Shortly thereafter, Good consulted with a husband and wife duo, Hanspeter Sigrist and Gabriele Madlener, about World Cup registration. (Hanspeter Sigrist was a Swiss coach, and Gabriele Madlener was responsible for various sport climbing activities of the Swiss Alpine Club.)

Granted, Susi Good was not the only climber from Switzerland interested in participating in international contests; she cites Philippe Steulet, Fred Nicole, and Elie Chevieux as inspirations. But none of those climbers had yet cracked into the top tier at World Cup level, and so the Swiss Alpine Club quickly accommodated Good's ambitions to compete.

Entering the Global Competition Stage

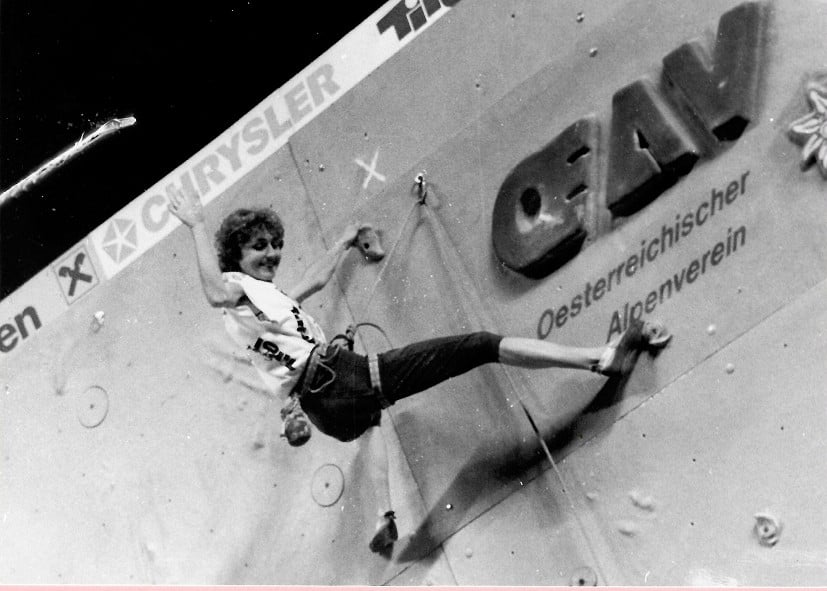

Regardless of the zeal, Good did not have the most auspicious start to her competitive career. Her first-ever event was a World Cup in Vienna in late April, 1990, and an initial nervousness that came with being on the roster almost wrecked her ability to perform in the competition's qualification round.

Fortunately, Good, 24 years old at the time, was able to keep the anxiety at bay and climb high enough to eke through to the semi-finals. (The rules at the time did not award points for specific handholds as they do now, and instead measured the highest point reached on the wall.) Her nervousness subsided in the semi-finals because, as Good recalls, "I thought that I had already gone far [in the results]." She eventually finished in 10th place.

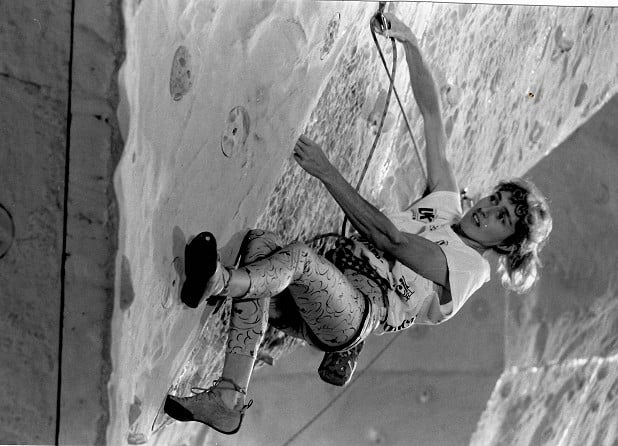

But having to deal with the great swings in emotions—from that near-crippling anxiety to surprising calm—proved that Good still had a lot to learn in competitions. This realisation came into greater focus at the next World Cup, in Madonna di Campiglio, Italy, a couple of months later. On one of the routes there, Good climbed to the crux—an overhanging roof section. In fact, it was the first roof section she had ever encountered, and she had to figure out how to climb it on the spot. "I had no idea how to do it," she reminisces. "I managed it, somehow, with my arm strength."

Good was able to muscle over the roof crux, but she eventually finished in 13th place. The biggest French star at the time, Isabelle Patissier, rocketed to a gold medal. It didn't exactly make for a razor-close rivalry; but in Patissier, Good witnessed the standard that was required to win World Cups.

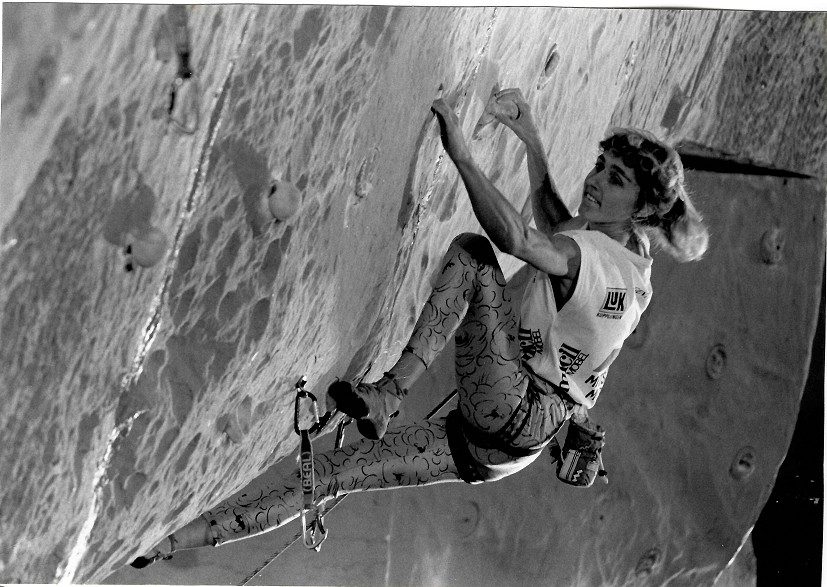

With that, a training routine developed: Good began climbing four days a week, weather-permitting. If climbing on real rock was not possible, Good would train on a wooden wall and romp through a seemingly never-ending litany of her true training love—pull-ups. In those days, mental training was not widespread on the World Cup circuit, but Good was able to identify strength in that area, too. "Perhaps my greatest talent was that I could always concentrate well on the routes and block out everything else," she says.

By the time a World Cup in Clusone, Italy, rolled around in August, 1991—approximately one year after that 13th place finish in Madonna di Campiglio—Susi Good had become a powerhouse of upper-body strength and mental fortitude. She had earned some bronze medals at prior World Cups, but this competition in Clusone was to be her star-making showcase: she won gold, and in the process beat Patissier, who earned silver.

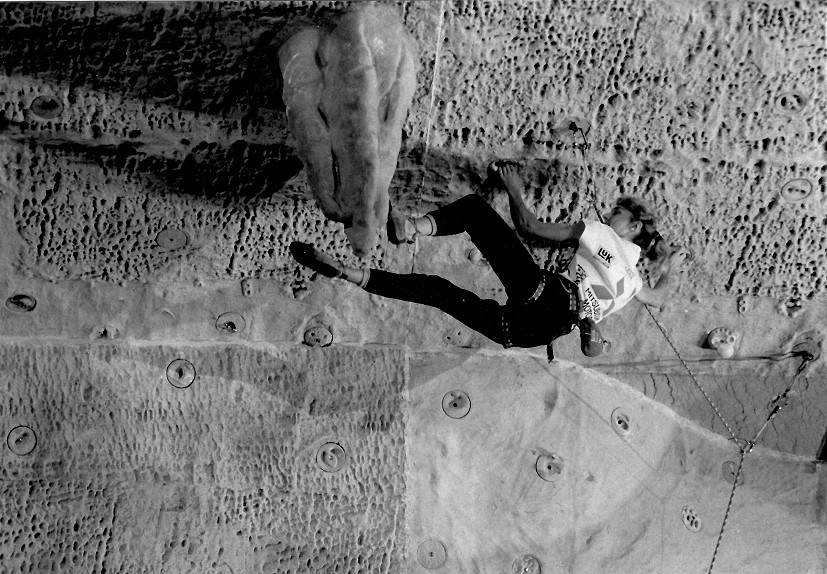

Yet, all prior accolades proved to be the prologue to climbing's first-ever World Championships, which were held in Frankfurt, Germany, approximately one month later. The event featured the same cast of characters—including France's Patissier—that Good had previously battled on the World Cup circuit. And like the memorable roof section from the World Cup in 1990, the eventual final route at the 1991 World Championships featured a unique crux—an enormous stalactite.

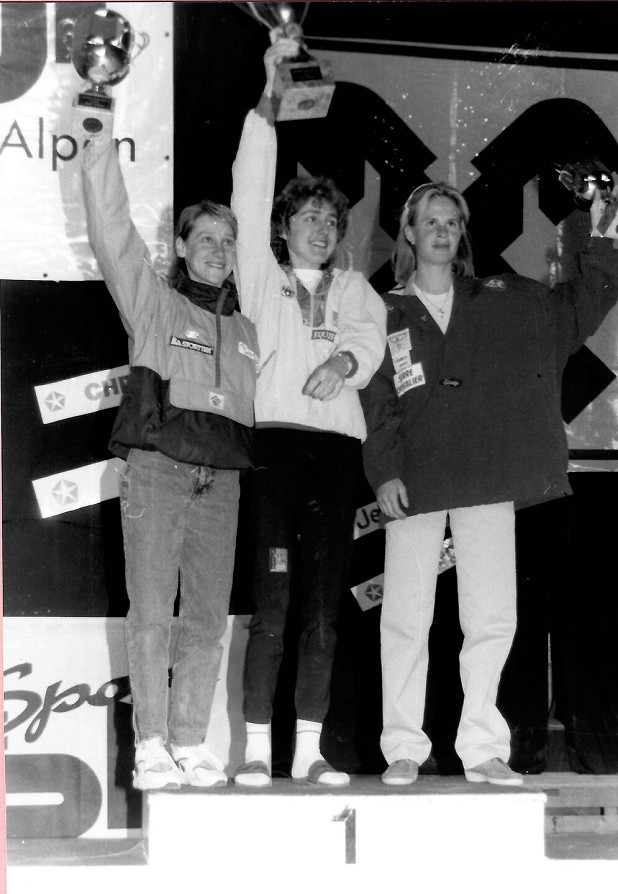

Once again, Good found herself battling nerves, but anchored by her enervating training regimen, she managed to focus enough on the route to climb higher than anyone else. In doing so, she won the gold and became the sport's first-ever world champion, joined on the podium by Patissier in second place and Robyn Erbesfield - mother of Sport Climbing Olympian Brooke Raboutou - in third.

Despite the epic clash that had just played out on the global stage, the women were close with one another off the routes. They had developed a system of hand signals to communicate and circumvent language barriers (Good spoke little English). As friendships grew with other competitors, so too did Good's celebrity. She became increasingly well-known around Switzerland. Once the accolade of a World Championship gold medal sank in, it fostered higher expectations. "For sure there [was] more pressure," Good explains. "You always want to win, or at least climb onto the podium. But this pressure came from myself—not from other people."

For a time, Good was able to balance everything in the seasons that followed. The year of her World Championship victory was followed by a year of back-to-back World Cup gold medals—in St. Pölten, Austria, and Laval, France, in 1992. She kicked off the 1993 World Cup season by winning another gold medal, which swiftly led into the 1993 World Championships in Innsbruck, Austria. As the defending world champion, Good was facing unprecedented pressure. Her parents were also in attendance, a rarity, which added to the gravity of the situation.

Befitting of so much exposition, the 1993 World Championships commenced with dramatic climbs that failed to adequately separate an incredibly stacked field. Good advanced to the World Championships' semi-final round and then the final, but neck-and-neck results with Erbesfield ultimately necessitated a World Championship superfinal (as opposed to the present-day tie-break method, which is to count back to standings from the previous round).

In this superfinal, the women were assigned the men's route. "We had to go directly into the route without trying it, but we had been allowed to watch the men," Good remembers. "Since I knew the climbers well, I knew which of the men climbed most like my climbing style."

In the end, Good narrowly out-climbed Erbesfield in the superfinal and won another World Championship gold medal. In doing so, Good became the first-ever back-to-back world champion in the women's division. It was a historic occasion, but few people realised that the win also marked the beginning of the end for Good's momentous competition career.

Leaving It All Behind

Good continued taking part in competitions around the world as the 1993 season drew to a close. (Notably, she appeared on a podium at every World Cup for the remainder of the 1993 season following her 1993 World Championship win). However, at the conclusion of the 1993 season, and to the shock of fans everywhere, Good chose to step away from competition. She wanted to alleviate some of the self-imposed stress and expectations that had accumulated in her four years of competition climbing stardom. "I had to learn to say, 'No,' from time to time—since I was suddenly allowed to, or supposed to, or expected to participate in many events," Good explains.

There were also physiological factors in Good's decision to take a break from competing. She had endured many multi-day World Cups, during which she had been, at times, holed up in her hotel room doing pull-ups in perpetuity—she was sick of that type of monastic existence. Additionally, in what would ultimately turn out to be her last year on the World Cup circuit, 1993, Good had started dealing with chronic back pain, and her fingers were perpetually injured — ailments that likely stemmed from a lack of rest days.

Good made a tentative plan to return to World Cups after a one-year hiatus. She was married by this point, and in her year of respite and recovery, she and her husband decided that they wanted to start a family. (Together they eventually had four kids: "I am very proud of them," Good adds). Formally trained as an architectural draftswoman, Good also took a job as a bookkeeper and started running a popular outdoor sporting goods store, Alpin Bergsport, in the Swiss town of Grabs alongside her husband.

Being actively involved in so many other activities, Good steadily slipped out of the global competition climbing consciousness; the single-year hiatus turned into a permanent departure. Meanwhile, the World Cup circuit chugged along without her. In the men's division at the 1995 World Championships, Good's Swiss compatriot, Elie Chevieux, earned a bronze medal—his first.

Roughly a decade later, another Swiss climber, Cedric Lachat, saw Switzerland once again represented on a World Championship podium, and Swiss boulderer Petra Klingler won World Championship gold in 2016. More recently, Switzerland's Sascha Lehmann won World Cup gold this 2023 season in Innsbruck, and fronted the campaign to host the IFSC World Championships in his home town of Bern. But all modern Swiss accolades were founded upon Good's earlier achievement in putting Switzerland on the global competition map.

To the more modern generation of competitors, Good urges, "the most important thing is not to lose the joy of climbing." She recommends young competitors visit a lot of climbing walls, boulder regularly to build power, and manage adequate rest days to keep the psyche and stay healthy.

Today, Good continues to climb at crags and gyms near her home in Switzerland. She still gets recognised by longtime fans of the competition scene from time to time. She is proud of her outdoor accomplishments too, even though the ascents don't often garner the long-lasting attention that the back-to-back World Championships do. She jokes that her personal best routes "are just good warm-up routes compared to what today's climbers climb," but she is nonetheless able to riff off an impressive resume of grades: "Many 8as and 8a+s, about 10 different 8bs and one 8b+," she says.

In response to the speculation about her whereabouts, which has mainly emerged as Internet chatter asking: 'Whatever happened to Susi Good'? Good says, unassumingly: "I still climb today, and I still like it very much."

When it comes to her legacy—of blazing onto the competition circuit, working with others to challenge Team France's dominance and make history—Good is modest, saying, "I was certainly not a pioneer." But embedded in that modesty is an acknowledgement of the tenacity that made Susi Good, at least for a few years, undeniably the best in the world: "I was just lucky that I climbed hard enough at the right time."

Special thanks to Daniela Pfister at the Swiss Alpine Club for help with translations for this piece.

Comments

Great article. I'd love to hear more about the characters of world cup climbing history.

Great article. Life must have been much more fulfilling for her with new career challenges and four children, rather than doing interminable pullups in hotel rooms. I was very active in the 90´s, read all the mags, and had always wondered what she had gotten up to after disappearing from the competition scene. All the best to her, and thanks for the article!

Pretty poor that a writer whose job it is to write about competition climbing doesn’t know who the first winner of the men’s World Cup was.

Jerry Moffat, legend that he is, was never an overall winner. It was Simon Nadin, in 1989. Jerry was 3rd overall but famously won the event held in Leeds.

Surely a writer about comps should know? It’s only a Google away after all. If the writer hasn’t fact checked something as basic this, maybe other points haven’t been checked either.

Worth adding that the women’s result is wrong too. In1989 Nanette Raybaud won, not Robyn Erbesfield. Erbesfield didn’t win till 1992.

Seems a bit harsh on the author. It wasn't the main focus of the story, just a historical sidenote. As far as I can make out from a quick Google, it's not so much complete nonsense as a slip on the terminology. It looks like Jerry Moffatt and Robyn Erbesfield won the first event of the 1989 World Cup series.

Incidentally, this old Guardian article I came across in the process is wonderful. An interesting mix of the usual silly descriptions from a non-climber and some actually mildly insightful remarks on the (still ongoing!) tensions in the BMC over competition climbing.

https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2012/nov/20/climbing-world-cup-simon-nadin-1989