Hanging off the belay, drained yet feeling very pleased with myself, I see an ice axe briefly appear at the edge of the climb then whack into the brittle ice amid a spray of ice chips followed closely by Matey's grinning face as he pulls over the bulge on the pillar. "Nice lead! You looked really relaxed on that pitch " he says clipping into the belay...

Fear and Stress

Like the swan moving gracefully across the smooth surface of a lake, with its feet going ten to the dozen under the water, so it is the same for the ice climber. Outwardly cool, focused, each tool placement an exercise in precision, assisting economical upward movement. Yet within the climber's head there is full on action as their brain struggles to deal with the vast amount of information that is vying to be processed.

When pushing personal boundaries and moving into the realm of the unexpected, where there is the possibility of a fall, real or imagined, then the climber has to be able to deal with a variety of conflicting psychological and physiological demands. These conflicting demands can be summed up in one word. Stress.

A manageable amount of stress gives the lead climber an exciting edge leading to an increase in the climber's performance. Not coping with that stress can lead to the exact opposite, which if you are lucky will see you back of a pitch; or if you are unlucky, wait until you are committed before the black dog of fear leaps out from the dark depths of your mind to throttle and constrict your upward progress, reducing it to a panicky heart in mouth upwards wobble. This article describes the relationship between our physical and mental performance on an ice climb, and gives some very simple, but easy to use Top Tips for managing your own physical and mental stress on a climb and helping you maintain that steely eyed focus.

Fight or Flight

In climbing fear can arise from many things, the most obvious being fear of falling - and on ice climbs falling is serious. Recent improvements in ice protection and equipment mean that ice protection is easier and faster to place, and given certain parameters such as the condition of the ice, more reliable. Still, the fact remains that taking a fall on an ice climb, with all that sharp metal stuff hanging off you, will more than likely lead to injury. So you see that on an ice route fear of injury is a real fear.

Humans have evolved a survival mechanism called 'flight or fight'. Simply put when faced with a threat we very quickly (sometimes instantaneously) evaluate the threat, see if we can overcome it i.e. fight it, or if not make a run for it. That's fine if running away from Big Bears or a bunch of nutters' hell bent on using your head as a household decoration, but it is a tad inconvenient when you are strung out and stapled to an ice pitch with your tools and ropes.

Whether we decide to stand and fight, or make for the hills our body sets us up for the forthcoming action by firing a huge dose of adrenaline into our system. This shot of adrenaline will produce an intense physical reaction in our bodies - that familiar fast beating heart, shallow breathing and butterflies in the stomach feeling. However, this adrenaline hit is a two edged sword. It can fire us up for undreamt of strength which well see us through the forthcoming action – or it can cause an adrenaline soaked, panicky rush.

The climber is faced with the challenge of controlling their state of 'arousal' such that they are maintaining a balance between the positive effects of this 'adrenaline rush' and it's destructive negative effects – panicky 'rushing'.

Initially whether we choose to stand and fight (Climb) or run away is a choice we make, and is affected by a variety of factors including past success (succeeding on climbing routes as challenging in the past), past failures (having a scare on similar climbs in the past), current emotional state (scared/relaxed due to the current situation), self confidence (I can do this!), and how committed to the climb you are (both mentally and physically). As we perhaps know all too well, although we may decide to leave the ground and start climbing, part way up the climb we might find ourselves facing an emotional crisis and a resultant change of heart. So how do we go about dealing with this potentially dangerous performance degrading set of behaviours?

The Ice Climbers Leading Skills Toolbox

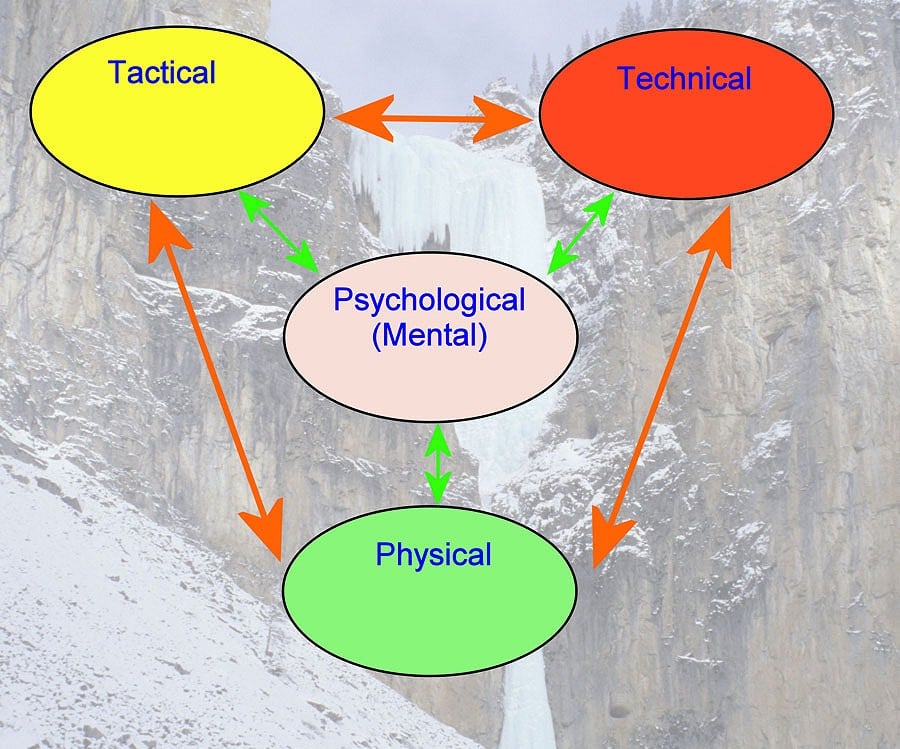

To see how individual aspects of our ice climbing relate to each other we can divide our climbing performance into four main complimentary components:

Physical – our muscular strength, power and endurance.

Technical – our climbing movement skills, use of tools, proficiency in using ice-climbing protection etc.

Tactical – how we go about climbing the route such as where we stop to place gear, rest, identify where the crux is etc.

Mental – what goes on in our heads and the strategies we have to manage this.

As Diagram 1 illustrates our mental skills i.e. our ability to manage the stress of leading (and not as in how psycho you are!) links all the other elements together. Our brain controls how everything else works, or doesn't. Each element in the loop has a direct and immediate effect on the others in the loop. As each element is fed through our brain it has a direct impact on our emotional state, likewise whatever is going on in our brains has an immediate impact on our physical performance - in effect a feedback loop.

So in our ice climbing our weakest element will have a profound effect on our overall performance, as our weaknesses pull us back more than our strengths pull us forward. So by identifying what is hindering your climbing and focusing on developing that element you will, theoretically at least, raise your overall game.

Ah but there's the rub. Many ice climbers who become pumped on a climb reckon if they could only become 'stronger' then all will be grand. Yet if they had a close look at the reasons why they became pumped they might find that this happened not because of their perceived weak, stick like skinny arms but because they were overtly 'aroused' i.e. they let the mental stress of the situation get the better of them and started to hold onto their tools too tightly for example.

What I will outline below are some very easy to learn and use techniques covering the technical, tactical and mental components of leading ice climbs. Developing techniques that assist us in staying relaxed, calm and controlled on an ice climb can mean we use our physical resources more efficiently and raise the chances of a safe, successful and stress free ascent.

Technical Top Tip

There is a key technique based top tip, sometimes overlooked by noobie ice climbers, which can go a long way to assisting our ideal of achieving a state of relaxed steely focus.

Despite advances in ice protection, the very nature of ice means protection can still be strenuous or difficult to place, and falling with all that metalwork dangling off you will still in all likelihood land you in hospital. To guard against this a basic concept in ice climbing is making sure each tool placement is as good as you can get. It is worth taking the time to ensure good placements, as opposed to making a poor placement, then saying 'bugger that - it's ok' and then placing the next tool whilst all the time worrying about whether that last one will hold! Chances are the next placement will be poor as you are too busy stressing about the last one. This cycle continues until a) you finish the pitch/find a rest, or b) your tools pop and you take a screamer.

Good placements are the key to running it out on a gnarly pitch. By ensuring each placement is solid i.e. is in itself an anchor you generate a great deal of confidence to push it out past your protection. The theory works on the basis if your feet or a placement blow the surviving placement(s) stop you taking a BIG FALL. I've seen this happen with one of my mates when pulling over an ice overhang. When the ice his feet were on collapsed. He fell onto his tools which luckily were well placed. After an adrenaline-fuelled couple of pull ups he re-established contact with the ice. Just as well as he was way above his last decent ice screw.

Although good technical technique is the key to climbing safely on ice, maintaining a relaxed focus will help you maintain and use best technique. As we have seen becoming scared leads to your body becoming physically tense with a resultant effect on our physical performance and co-ordination.

In ice climbing this sees the climber grip their tools tighter, with the result that their forearms become pumped. As your arms become pumped so does this affect your swing and your ability to place your tools with the resultant 'jelly arm'. As the placements become poorer so you become more scared. Your footwork will also be affected as you stamp and stomp your front points into the ice in an effort to achieve something that feels like a stable platform.

To maintain focus and deal with this physical and mental arousal the climber can use a basic set of mental skills.

Breathing

Here is a small experiment...

Sitting down pick up a pen or pencil in your hand. Start to twirl the pen/pencil between your thumb and fingers – ensure this is done at steady rate.

Now hold your breath for as long as you can whilst twirling the pen.

What did you notice happening to your ability to twirl the pen and the speed it was twirling?

How would you describe your emotional state during the exercise?

Here is another small experiment.

You can do this whilst doing the same pen-twirling motion.

Sit yourself down in a comfortable position.

Imagine a length of thread is attached to the top of your head, and then imagine this being gently pulled such that it lifts your head up.

Next take in a deep breath through your nose as you count to four, slowly (as you take this breath imagine a lead ball inside your belly, which gently and slowly sinks down into the bottom of your belly as you breath in).

At the end of this in-breath start to breath out, again slowly, through your mouth for another count of four.

What did you notice happening to your ability to twirl the pen and the speed it was twirling?

How would you describe your emotional state during the exercise?

How did that compare with the previous exercise?

Hopefully what you will have noticed is that in the first exercise the pen should have started to twirl a bit faster and bit more erratically as the lack of oxygen causes you to start stressing. In the second exercise the speed and ease at which you twirled the pen will have stayed the same, and you will have felt relaxed.

Do you hold your breath when you climb?

That last question might not have an obvious answer. Based on my experience of teaching and coaching climbing I'd say the majority of climbers would tend to hold their breath whilst moving, or at least take very shallow breaths such that at the end of the pitch they will be gasping. Not from the aerobic demands of the pitch but simply from not breathing enough.

Using breathing to control your emotional state is very simple. In fact controlled deep breathing is used a great deal in a variety of meditation and martial arts practice.

You can use this breathing technique whilst climbing when you reach a suitable rest point and become aware that your breathing is fast and shallow. Do the deep breathing exercise for a count of four cycles.

You can also co-ordinate your breathing with your movement, although this takes a lot of practice. As you move you breathe out through your mouth. You move for as long as you breathe out. Re-establish your balance, breathe, then next time you move, breathe out. At first this will tend to feel very awkward, but with practice this will you to maintain a nice steady, relaxed and flowing climbing movement.

Self Talk

Imagine whilst you are climbing that your mate belaying you is constantly shouting up at you telling you how crap you are, how poor those placements are, how hard the climb is and how weak you are. What effect do you think that will have on your climbing performance?

Now imagine your mate down at the belay is occasionally shouting up how great you look, how solid those placements are and generally being encouraging. What effect do you think that will have on your climbing performance? A more positive effect perhaps?

Now I'm not suggesting that you have your mate shout up positive things at the crag but your inner voice is the voice that you hear all the time whilst climbing. For many people this inner voice has a tendency to focus on the negative and scary aspects of running it out past your gear – this will have the same effect as your mate shouting negative comments – undermining your self-confidence.

Self-talk is a simple but extremely powerful tool. With self-talk you harness the power of this inner voice by having it support and encourage good technique. So as you climb you consciously have your inner voice say stuff such as –

"That's great you are moving well"

"Good placement. Excellent! Trust it place the next tool, Good now move your feet up. Breath out and relax. Excellent"

"Remember to keep breathing – good"

And so on. Here the key is to have your inner voice emphasise good technique and/or positive behaviours and reward it with praise. You can do this either quietly to yourself, or some climbers find that talking out loud helps them. Whatever works for you.

I guess many of us just stroll up to the base of our ice climb, have a cursory glance at it and then fire up the climb. By taking some time to 'scope' out the climb we can perhaps learn more about the route and hence decide on a better strategy that will positively weight the chances of our making a successful ascent.

So before firing onto the climb take some time to look at the climb, if need be you can use a pair of binoculars to see the detail a bit more clearly. What you are looking for is to decide on the best line and tactic to successfully climb the route. Some key factors to be looking out for:

What line looks to have the best ice?

Here you are looking for ice that is going to offer good placements for your tools, and take good ice screws. What is good ice? That's an article in it's own right, but simply put you are looking for ice that appears to be more blue in colour. The whiter the ice the more air is in it and the less likely it will be to provide you with bomber ice screw placements.

Where can you get a rest(s) to shake out and place some gear?

There may well be sections where the ice is so steep (and stopping to place gear will be very tiring) that may be unavoidable – can you power through that safely or are you just climbing further on up into a state of total commitment...

By identifying places where you can get a rest you can break the pitch down into sections. This allows you to ensure you get a physical rest whilst on the climb, but mentally you can deal with climb by breaking it down into achievable sections. As the old saying goes –

"How do you eat an elephant?

A piece at a time..."

Hazards?

Check out what is above your proposed line. Here things like other climbing teams (My own personal rule is I never, ever, ever follow someone else up and ice climb unless I know I can climb well out of the fall line. Falling debris can and does kill), hanging icicles falling off, avalanche etc should all be assessed for the probability of them occurring before you start climbing.

Summary

Leading steep water ice is a head game. It demands an ability to maintain your cool whilst climbing above protection that might at best be adequate or strenuous and challenging to place, on terrain that is slowly but relentlessly sapping your strength. Given the inherent seriousness of leading ice routes panicking and risking a fall have grave consequences.

The key to holding it all together whilst climbing is maintaining a calm and focussed emotional state. Developing a good mental skills toolbox is just as important to a successful and safe ascent as learning how to use the latest and grooviest ice climbing toys.

So next time you are cranking it out on the ice focus on each tool placement and make it bomber, concentrate on your breathing and have that inner voice cheer you on.

Top Ice Climbing Tips

- Take the time to ensure all your tool placements are bomber (well placed not over driven) – think of them as runners.

- Using simple techniques such as deep breathing or self talk help stay relaxed when climbing thus rationing your strength i.e. less over gripping of your tools.

- Scope out your climb before hand and decide on the best tactics to climb it i.e. where the crux is, where you can rest, where you can place gear etc.

George McEwan is based in Aviemore, Scotland and is a Senior Instructor at Glenmore Lodge (the National Outdoor Training Centre) and is the Technical Officer for the Association of Mountaineering Instructors (AMI).

George has been climbing and mountaineering for over twenty years. In that time he has put up numerous first ascents both in the UK, Europe and Nepal.

He has climbed mostly in the French Alps around Mount Blanc, both summer and winter. Also climbed in New Zealand Alps. Expedition to Langtang Valley, Nepal 1st ascent of the North Ridge North face Naya Kanga 1989. Second British Expedition to Tien Shan for attempt on South Face of Khan Tengri 1993. 1999 trip to Alaska to attempt Nettle - Quirk route on Mt Huntington, then West Ridge of Mt Hunter.

In the past few years his climbing has focussed primarily on waterfall ice climbing, with this passion taking him to Canada, Colorado, France, Italy, Austria and Switzerland.

His professional career has spanned seventeen years during which he has worked for Outward Bound, and for the past thirteen years with Scotland's premier National Outdoor Training Centre - Glenmore Lodge where he currently works as a Senior Instructor.

Although actively involved in all forms of climbing from bouldering through to ice climbing, George's primary passion is steep water ice.

- IMPROVE: Steep Ice Climbing Technique 5 Jan, 2016

- Essential Winter Skills: Ice Axe Self Arrest 5 Mar, 2015

- Ice Climbing Anchor Strength - Analysis 30 Jan, 2012

- Protecting Winter Belays - Safety Tips 16 Jan, 2012

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Colorado Ice 28 Feb, 2009

- Glenmore Lodge: 60 Years Involvement in Climbing and Mountaineer 9 Oct, 2008

Comments