Many readers may struggle to place Tajikistan on a map, so let me begin there. It is a mountainous, landlocked country bordering China to the east, Afghanistan to the south, Uzbekistan to the north and west, Kyrgyzstan to the north. The capital city, Dushanbe, features the world’s tallest flagpole and the world’s largest teahouse (under construction).

Most of the country is covered by the Pamir mountains, up to 7,000m altitude. While relatively off the radar as far as current western mountaineering is concerned, the Pamirs have an important historical link to British mountaineering as it is here that the British climbers Robin Smith and Wilfrid Noyce tragically died in 1962 whilst on one of very few western climbing expeditions permitted to visit the Pamir during the Soviet era.

Nowadays the Pamir mountains are accessible to visitors from all over the world. I have been on 2 mountaineering trips to Tajikistan and can strongly recommend it as a destination. It has better weather than the Alps, cheap permits, good food, is safe for visitors and contains range after range of barely explored mountains with good first ascents there for the taking by climbers of modest technical ability such as myself.

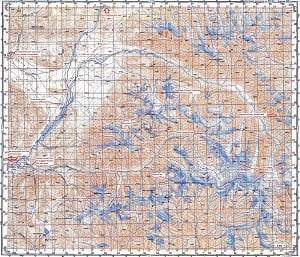

For 2 years now, the Muzkol range in the eastern Pamir has been bothering me. Access from Dushanbe requires a 12-14 hour day driving mainly on dirt tracks along the Afghan border to Khorog, the capital of the eastern province of Gorno-Badakhshan, then a day driving along the Pamir highway (also mainly dirt track) to the town of Murgab close to the Chinese border (Muztagh Ata is visible from here). Next is a day of off-road driving then (depending where in the range you want to climb) probably a few days of carrying your equipment to a suitable basecamp. Access is further complicated by difficult river crossings and lack of knowledge about where vehicles can go. Expeditions did visit the Muzkol during and since the Soviet era but enormous potential for new routes remains, including unclimbed peaks up to 6,000m altitude.

In July last year we had everything ready to go to climb in the Muzkol, only for some serious trouble to kick off in Gorno-Badakhshan a week before departure. We did attempt to gain access after the situation had calmed, but were turned back at a military checkpoint en-route to Khorog.

So we duly set off for the alternative mountain range that we had researched at the last moment – the Peter 1st Range near Jirgatal at the top of the Rasht valley. This was a shared taxi ride with a difference. On the way towards Khorog, our poor taxi driver had been waved down by the traffic police to pay a bribe every 30 minutes but this time, we were sharing the taxi with an officer from the secret police. He had an ID card identifying him as such, acting as some kind of “Don’t-mess-with-me” card as every time the traffic police flagged us down, he merely showed them his card and we were waved through bribe-free.

We stayed the night in Jirgatal and arranged for someone to drive us to Ming-Bulak, the last village on the way to the mountains, the following morning. At Ming-Bulak one of the more comic episodes of the trip occurred. One of the villagers owned a 4x4, and we agreed a price for him to drive us up into the mountains. After the deal was done, he invited us into his house for tea. As is the normal practice, a cloth was laid out on the floor about which we sat as we all partook of tea, bread, sweets, and a range of home-made dairy products.

However our host assumed that, as foreigners, we would prefer coffee, so coffee was duly produced. A tin of instant coffee, no less, which was opened with a tin opener for our perusal. It appeared that our host had owned this tin of coffee for some time as it was rusty on the outside. Our host also believed that coffee is something that you put in tea. Ed explained that you actually drink it on its own in hot water and our host’s wife duly produced a pot of hot water for the coffee. Our host boasted that he had 7 sons. Later it emerged that he also had some daughters, as I was asked if I would like to marry one of them. I politely declined.

We drove up towards the mountains, through high pastures inhabited in the summer by livestock farmers – living in mud huts or yurts. We were constantly invited in for tea, bread, sweets and various dairy products. Most people here were fasting for Ramadan, but were still very keen to invite us in and give us food – as non-believers we were not expected to fast.

We were dropped off near the snout of an 8 km long glacier that descends from the 3 highest peaks in the range (Piks Tyndall, Agashidze and Agasis – all just under 6000m) and spent 2 days carrying rucksacks full of food and gear up the glacier to a basecamp on the moraine. Following acclimatization to 5,000m we set out to climb the north face of Pik Agashidze. It is just over 2000m high (topping out at 5900m) but with a start up the rock section we reckoned that we could get up and down it in 3 days.

We packed our stuff and went to bed ready for an early start the next day. Things got off to a bad start when our petrol stove packed in and after eventually coaxing it into action we made a brew, packed the stove in our bags and set off. Initially we made good progress. We crossed the glacier and moved together up ~100m of grade I-III ground to reach a snowfield beneath the rock section. We dithered a bit traversing left to a couloir, finding evidence of rockfall beneath it then traversing back to go up a different couloir. We cramponed up the couloir until it petered out then set off right up a rocky rib. We spent most of the day rock climbing in crampons up this rib, moving just about fast enough up increasingly interesting terrain.

In terms of character, the climbing reminded me a lot of the looser and less well-frequented parts of the Cuillin on Skye. There was enough solid rock to make progress but also an awful lot of very loose rock. You did need to be careful. At one point I effortlessly trundled a 4’ high pinnacle all the way down to the glacier below.

But as we went higher the terrain was not changing as expected. From our viewing through binoculars it had appeared that as you went higher the rock area sloped away into the main face, becoming less steep and therefore easier. But in actual fact, it was getting harder. At around 6pm there was a pitch that made us consider our position. It became sufficiently hard to make us really slow. I had to take my crampons off and sack haul to get up an overhang. I probably pulled on the gear as well. More difficult terrain was visible ahead.

We had to accept that there was no way we were going to succeed in climbing this in the 3 days we had planned. But we only had enough food for 3 days and, even more to the point, we had (via the satellite phone which we had left at base camp while we climbed) told our friends back in the UK to raise the alarm if we were not back after that time. So we reluctantly decided to turn back. We bivvied where we were, ready to descend the following day. The terrain justified keeping our climbing harnesses on and staying attached to a belay whilst in our sleeping bags, but at least it was not completely vertical, we were semi-horizontal.

It was a difficult and frustrating decision to have to make as the ground ahead of us was definitely climbable – I am certain that the route would go if you allowed 4 days rather than 3, but we did not have 4 days and certainly did not have time for a second attempt. After a character-building descent, we carried our stuff back to the nearest settlement over the next 2 days, were fed by locals and travelled back to Dushanbe. Our arrival in Dushanbe co-incided with Eid, a happy co-incidence as myself and my climbing partner had both lost about 5kg.

But the lure of the unclimbed peaks of the Muzkol remained so I planned another trip for this summer, leaving nothing to chance. Unfortunately my climbing partner from last year (Ed Lemon) could not take part this year due to work commitments so I recruited another climbing partner (Jonathan Davey) and we set about planning our trip. After a few months of organization and anticipation we flew from Manchester to Dushanbe via Istanbul on 20th July. We stumbled bleary-eyed off the overnight flight at 6am and onto the taxi rank to negotiate. Taxi drivers were utterly incredulous when I told them I knew the normal fare was $5 or $6 (rather than $20), but eventually someone agreed to take us for $7. The taxi driver tore forwards and we were on our way. Why do they all drive like maniacs? Petrol is very expensive here relative to people’s incomes. Hasn’t anyone told them that you use less of it if you drive sensibly? Anyway, we had arrived.

After a few days food shopping in the bazaars of Dushanbe we were finally ready to depart for the Pamirs. Better luck this time? Yes. We passed hassle-free through the checkpoint where last year we were stopped and were free to concentrate on the spectacular scenery. The Tajik side of the Panj river features (albeit decaying) Soviet infrastructure, while the Afghan side features communities with a subsistence farming way of life unchanged for many centuries.

As described at the beginning, the journey to the Muzkol range is a long one. After a couple of days of on-road driving to the nearest town (Murgab), we arranged for a driver with a Russian Uaz 4x4 to drive us as far as possible off-road to the mountains. We were dropped off at the end of a dirt track, about 40km from the nearest small settlement and 75km from the Pamir highway. We hoped very much that our driver would remember to come to pick us up on the appointed date (don’t worry – he did). Next were 2 days of carrying 25kg rucksacks to establish a basecamp as far up the Bozbaital valley as possible. The thermometer on Jonathan’s watch topped 55°c during the afternoon. I don’t quite believe that reading, but it was certainly 45°c. Needless to say, in these conditions we did not get as far up the valley as we had wanted to – leaving us with a longer walk-in for each climb. But never mind. Eventually we had everything unpacked at basecamp, rested, went up to 5,000m to acclimatise, rested again and were finally ready to climb.

But what to climb? We had hoped to attempt one of the unclimbed 6,000m peaks near the top of the valley, but they were still a long walk away and, even more to the point, we didn’t feel ready for 6,000m having only acclimatized to 5,000m. So we cast around on the map and found something good. A glacier with unclimbed peaks up to 5,700m altitude that was up a side valley not too far from us. In the event, the walk-in to a camp on the glacier up this side valley took a further 2 days as it involved a river crossing which could only be done early in the morning via a pendulum traverse on the rope. All good exciting stuff. But finally, we were camped on the glacier and ready to do a climb. We took some photos of our objective to refer to as we climbed and set our alarms for 4am.

And what of the climb? It almost seems like a minor appendix to the description of the 2 years spent trying to get to this range of mountains but we climbed the point shown in the last photo. In the photo it gives the appearance of being a distinct mountain in its own right, but unfortunately upon reaching the summit it turned out to be only a minor point along the ridge. We’ll have to name it “point something-or-other” rather than “peak something-or-other” to reflect this. Still a good route however, with 1,000m of ascent up alpine ice fields (topping out at 5,600m) followed by a somewhat character-building descent down west-facing couloirs and snow-slopes on the other side. The day ended with a long walk back down the glacier spent mainly trying to find our way through a maze of penitentes in the dark. What a day! We sure slept soundly upon our return to the tent, despite the jumble of rocks poking through the floor and our ineffectual rollmats. Back in Dushanbe we ate an enormous amount of Shashlik and other goodies. Nom nom nom!

You can read more (a LOT more) on our blog . We are gradually writing up the trip as time permits so keep checking back! Also you can view photos from last year’s escapades on my flickr account. Last year emphasis in photos is on the earlier parts of the trip before the camera battery went flat!

We would like to sincerely thank our sponsor, Gore-tex who generously awarded us a Shipton-Tilman grant to the tune of $1,600.

Comments