If you spend a lot of time in climbing walls you will see people falling off. Falling off bouldering walls, top ropes, lead climbs. If these walls are overhanging, you often see people's feet slip off holds, their bodies take wild swings and then the next 20 seconds will be spent in a valiant effort trying to put that toe back on the hold – to no avail. Another common sight is when a climber is trying to make a big move, certainly in reach, but as they go up for the hold, their bums stick out and pull them off.

These are both signs that the middle bit of our bodies is a bit soft. I don't mean fat, I mean weak.

The core muscles are very important in climbing and only recently are people starting to realise this. In this article I have once again returned to the source of knowledge, Nina Leonfellner, to find out what our "core" actually is, why it is so important and how we can train it to improve our climbing.

So Nina, what are our core muscles?

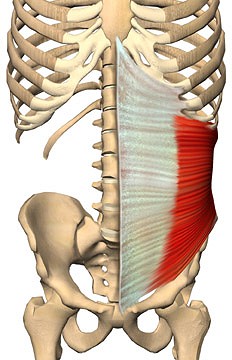

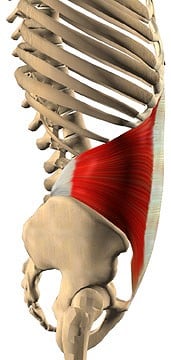

Our core muscles are the inner, deepest layer of postural muscles that envelope our torso, hips and pelvis. Our "core" means the deepest muscle layer of the centre of our bodies, it does not mean abdominal muscles. The deep abdominal muscles are part of our core, but does not define the core. Technically, our "core" is the centre of our bodies, of which our limbs attach onto.

For those who are interested, the deep, postural muscles comprising your "core" are: your breathing, laughing, and coughing muscles within your rib cage, your main breathing muscle, the diaphragm, your deep abdominal muscles named - Transverses Abdominus and Obliques, your pelvic floor (muscles that stop urination), Quadratus Lumborum (QL) a rib cage, pelvis and back muscle. Other deep back muscles such as Multifidus, Erector Spinae, Longissimus and deep Rotator muscles of the spine. Part of our torso is our shoulder blades, so, these are considered part of the core. Our shoulder blade muscles are our trapezius muscles, Levator Scapulae, Rhomboids and Serratus Anterior. Hips and pelvis are generally included as part of the core because the spine/torso sits within them, and are directly affected by their movements and strength. The deep hip and pelvis muscles consist of the deep glutes, deep hip rotators, deep hip flexors (Psoas/Iliacus). They are also considered part of our core because some of the hip and pelvis muscles are also spine muscles.

Ok, so what do they do and how do they work?

When speaking about core muscles, we have to also speak about "stability" muscles. Stability muscles are ALL the deep muscles of your body that do the same thing that your core muscles do to your torso, hips and pelvis. A stable structure means that it is firmly fixed and not likely to give way. So, our stability muscles, also called postural muscles, help prevent our joints and tendons from giving way under load. These muscles, including our "core" muscles gently compress and centre our joints statically and dynamically, i.e.: while we are moving.

We have two layers of deep stability muscles and an outer third layer which are powerful, mover muscles. The outer third layer are the muscles we can see under our skin, for example: pectorals, lats, bicep, and quads. These muscles are the long, big muscles that generally span 2 or more joints, therefore, being able to affect movement across many joints quickly. If our deep stability muscles are weak, or, are not engaged when they need to be, then the movers will have to take over. The big mover muscles have long levers of pull which do not compress and stabilise our joints and surrounding tendons, so this is where faulty movement patterns happen which can lead to injury.

Stability muscles, including our core muscles, compress our joints just enough to still allow movement, but controlled movement, that promotes centering. This is to prevent our joints and tendons sloshing around and giving way. Our ligaments, joint surfaces, the inner, spongy cartilage of our joints, and our tendons that surround our joints get affected by this giving way strain, which when habitual, becomes a repetitive strain. This is a main reason for tendinopathies, for example, elbow and shoulder problems for climbers.

Stability muscles, including your core muscles, need to be able to work at low and high load, be reactive. So, they need to work on more of an endurance level with varying positions, movements and progressions of resistance. Form, alignment of joints and staying "centered" is paramount for them to engage well, and timing is also important, so starting slow and controlled to begin with, but then training fast and complicated movement patterns are essential to build their timing and reflexive abilities, and hence be a more robust, responsive structure.

Your core muscles are the deep muscles of your body's centre: torso, hips and pelvis and these muscles hold and compress this area of your body to establish a solid/stable platform for your limbs to move from. They need to allow movement, but it should be controlled movement with joints staying centred, so they can close or lengthen easily and quickly, as well as when centered, joints and their associated tendons are strongest due to length/tension strength curves, and the ligaments and tendons surrounding a joint are not compressed, nor over-stretched.

Too much sitting shuts off the centre of our bodies. In our society we sit from a young age in schools, children sit in prams, car seats, strollers, sit in front of TVs, game stations, then onto desk jobs. I believe in the western world we are often disconnected with healthy postures and good movement patterns. We also pick up and mimic postures and movement patterns from our parents and role models. So, faulty movement patterns and poor awareness of healthy postures and positions is extremely common. I believe most individuals can benefit from stability and core training.

Stability and core exercises are essentially the same thing, as when you are working your core you are working your stability muscles, and vice versa. Depending on the positions against gravity and movements used, you can target different aspects of your core stability muscles. Some people will be strong in certain areas and weak in others. This is why ultimately, it is a good idea to have an assessment done by a physiotherapist, personal trainer, or coach with knowledge in this area.

Right, that's good to know, but how does this translate to climbing?

"Body tension" is engaging your core. This is a cue that coaches and therapists use all the time to cue climbers to pull or press tension throughout their bodies, from toes right up to finger tips. The bit in the middle is your "core". And sometimes the bit in the middle does not engage as well as it should, or, is weak from previous or current injury, or, slack because the climber has been sat at a desk all day and their centres are switched off and disengaged with the rest of their body and mind.

Your core is meant to work with you with every pull, press, rock over, high step, dead point and dyno. The inner, deepest muscle layer of your pelvis and spine gently compress these areas by pulling in and up from the bottom (pelvic floor), pull in from the front (deep and lower abdominals, compress in from behind (deep back muscles) and press down from the top (diaphragm: main breathing muscle). This creates a pressurised compartment that is stable and will not give way, and establishes a solid platform for your legs and arms to move from, but also is the start of force generation and tensile strength, and potential energy for recoil strength when you do a move. Engaging this way will help make your moves more efficient and powerful.

The second inner layer, which is still part of your core and stability muscles, will then engage to help rotate, and centre your hips and shoulder blades to keep your shoulders and hips in good alignment, which then helps to keep elbows, wrists, hands, feet and ankles in good alignment. This is why core exercises are important for preventing and/or rehabilitating most injuries. This is also why core exercises are excellent warm ups to any form of climbing, as you are switching on and preparing these muscles to work for you in your session. Also, being at the centre of your body where all the big blood vessels are, using your core muscles will get your circulation going and hence will warm you up for climbing.

Do you think that working your core will benefit you at any grade?

YES. For all the reasons explained in this article. Anyone, regardless of grade can be a desk job worker or a student who sits and deactivates their core on a daily basis. Anyone, especially novices, are at risk of injury if their core is weak. Anyone at any level can achieve a better climbing grade if their core is stronger than it is today.

When seeking coaching or advice, most climbers are aware of their lack of fitness or climbing strength, and sometimes their technique, however, not many people are aware of their core weaknesses. What are the signs of a weak core that we may experience during a usual climbing session?

Feeling like you cannot drive properly from your legs and hips is a very important sign that your core is weak in the position you are in, or for the move you want to do. Sometimes changing your position (getting in good alignment) can help you engage your core more. Hip flexibility is also important in this case, but even if you are flexible in that position, you also have to be strong.

I describe this feeling as "umpf"! Warming up and activating your core can give you the gusto or "umpf" you need to pull moves that you find hard. If you are feeling tired or demotivated before a session, then warm up your core and you will have a better session. Gymnasts and martial artists do this all the time and perform powerful, engaging movements all the time. Climbing is quite similar.

Another sign of a weak core is if you are struggling on steep routes or problems, especially if your feet, then legs swing off your footholds and you are slow, or have trouble getting them back on the wall or the foot holds.

The most obvious sign of a weak core is if you are experiencing common elbow and/or shoulder tendinopathies. As already mentioned, a weak centre will mean that your arms will have to pull harder in often positions of poor alignment.

A lot of climbing wall users are intimidated by steep, overhanging routes and/or bouldering walls, and stick to vertical walls as a result. Can a weak core still be identified on this ground?

YES, you need a strong core, especially in the hips and pelvis, to preform high steps and rock overs. The "umpf" I'm on about is especially important to perform these moves, especially to avoid knackering your knees. If you simply step your foot onto a hold and pull up, or heel hook and go, it will be harder on your knees, shoulders and elbows, as well as, more cumbersome, than aiming your foot, toe(s), or heel onto the foothold, pull your lower abbs and pelvic floor up and in, and then throw your hips over your foot or ankle. Engaging your inner pelvic layer first will give you the "umpf", as well as create a stable platform for your leg to press up from or pull into the foothold. If your deep-hip and torso muscles are also strong and responsive, then this will help further drive the rock over, high step, or heel hook. This will all help to offload your arms and save some finger strength.

Good exercises to train high steps and rock overs are front and side step-ups. They are not core exercises per say, but you could train your stability muscles, once you achieve good form, by stepping up onto unstable surface, like an air cushion, foam or thermarest. The higher the surface, the harder, but you have to make sure your knee, hip and pelvis stay aligned and not kinked.

A good exercise to train heel hooking is the single leg bridge. Again pelvis and leg alignment are paramount, and you can challenge your stability muscles by heel digging onto unstable surfaces like suspension straps ex: FIT KIT PRO straps, stability balls, foam, etc. Generally speaking people are calf and hamstring, or lower back dominant in this exercise, so you have to position your foot in a way that helps to engage your glutes and pelvis as well. You may also have to shorten the lever by bending your leg, or start on a stable surface first, and work a variety of positions before moving onto unstable surfaces. If you struggle to feel the right places work, get advice from a therapist or coach.

I see many people who seem to give up on steep ground if their feet pop off. This is particularly common in young climbers. Is this due to weak core and inability to raise their legs to place their feet back on the wall?

YES, and yes again. You need to coach them how to engage their core and get them to read this article!

Are bums hanging low on roofs and dynamic moves ending with a climber coming off the wall signs of a weak core?

To a large extent, YES. This demonstrates poor body tension and lack of centre engagement, or a lack of strength for the move that a climber wants to do. The stronger the middle section is, including hips and pelvis, the less likely this will happen. Of course this happens when the hand holds are too hard, or at a level that is at, or past our limit, but having a strong centre can help you hold on that little bit longer by tensioning our bodies close to the wall, and by also holding our arms and shoulders in good alignment, which makes our muscles recruit better, hence making us stronger.

Are weak cores more common in young climbers?

I cannot say a definite yes or no to that question. As it will totally depend on the background of what each child has had as far as exercise and play goes. This is why screening is so important, because it highlights these sorts of issues. I can say almost for definite that a child who has spent a lot of time in a buggy, push chair, on a sofa and then classroom chairs, will almost certainly have a weak core. Children are meant to be active right from the start. They are meant to have tummy time as a newborn, to help their back extensors develop after being flexed in the womb, they are then meant to be exposed to supported sitting, standing, crawling and cruising until they walk. Then running, jumping and play develops after that, which should include things that challenge and develop our core, like playing on the monkey bars, planks and playground equipment. Kids need to be exposed to active play and exercise A LOT. It breaks my heart when I see or hear about children, even teens, not having enough PE, or play time at school, or if a parent is limiting a child's potential in the playground. Children need to have the opportunity to be active. Children who are not that active will most definitely have a weak core, which can set them up for lower back pain as well as other repetitive strain injuries later on.

I think there is a common conception that shorter people have stronger cores, is this true?

Not to my knowledge. With respect to climbing, short people have a lever advantage when climbing steep ground and when climbing vertical routes they can often use more intermediate hand and foot holds in a less awkward way, which makes it easier to get up a route, occasionally. Also, shorter people or children have small hands and fingers, so small hand holds are relatively bigger than for a taller person with bigger hands and fingers. So, these advantages can make them appear to have a strong core, but I am not sure that it means their core (which means inner, postural muscle strength) is stronger than tall people. I think tall people are at a disadvantage of "fitting" into average things like seats, standing over average counter heights, speaking to the average height person, passing through average height doors, and so on. To "fit" into these situations, a tall person must slouch, or lower themselves in some way. The way that we see most tall people conform to most average settings is by slouching their spines to lower themselves. This slouching of the spine will over time, weaken their core because the muscles are in a position of disadvantage to fire up, therefore they will not be "recruited" as often as they should. Combine this with sitting a lot for whatever reason, and their core will be even more at a disadvantage. So, one could argue that taller people may have a weak core. But for day to day things, a short person will have to adapt in ways that may not be ideal for their core as well, so they will likely have issues as well. This is why desk job workers who are petite, or taller than average should have a size small or large chair and desk arrangement, and should not settle, or "fit in" average chair and desk set ups that most offices have in place.

Many generic core exercises will undoubtedly address some of our weaknesses, but are they climbing specific?

Some are, some aren't. Anything involving hanging is more climbing specific, however, any "core" exercise is good if performed well. The one thing to note is that core strengthening means strengthening your inner layer and outer layer of your torso and hips, not simply abdominal exercises.

Examples of exercises that are good for CORE ISOLATION and learning what and where your core is can be found below.

All of these exercises should be performed slowly and in control maintaining good form/alignment as your main goal. You are training deep, postural muscles which means they work all day long, and, throughout a climbing session, so you need to train them for endurance. You can mix and match slow, fast reps, and static holds from 10-60 seconds. You can change the exercise or move within the exercise but your "centre/core" is working and engaging, ideally for 1-5 minutes. If you are really weak, then starting 10 sec x 3-10 reps, but you should progress that to a length of time you need to climb a route/pitch, or boulder problem. the harder you want to climb, the harder the exercise should be!

EQUIPMENT:

Using equipment that adds an "instability" to your position, posture, or movement will train the deep postural muscles more than a stable surface, or object that you are manipulating. This will also train your reflexes, as well as speed and timing of how you recruit your muscles, which is really relevant to sport. Climbing requires quick and precise muscle recruitment a lot of the time, especially in the higher grades, and if your body can hold itself in a "centred" posture while doing so, then you can help prevent injury. Your muscles are also strongest when your joints are positioned in a centered alignment.

TECHNIQUE:

With all of these exercises you want to think about your deepest pelvic layer even before you "brace" or move. You imagine you are gently "stopping your wee" to engage your pelvic floor, and gently pull your lower belly (under your navel) up and in.

If you are "bracing" or pulling in your centre (core) then you want to keep your shoulders in line with your hips, and your pelvis "neutral" or "centred", which means in the middle of a tucked and tilted position. This middle pelvic position is when your pelvis and lower back are not OVER arched, or tucked flat, it is in the middle of those two positions. In other words this "centered" position of the pelvis is when your pelvis is slightly arched forwards and your lower back is slightly curved. This position should feel comfortable. Hold this position while preforming the described exercises. If you find it difficult to hold then the exercise is too advanced for you.

When lifting an arm or arms, use your shoulder blade muscles that are part of your torso (read my shoulder article on UKC). When lifting your leg(s), think deep pelvic muscles first and deep hip muscles second. You want to generally maintain torso and hips like a "plank" or a box with shoulders and hips in line, unless you add torso rotation or sideways movement. If you add rotation to shoulders and torso, or torso and hips, then try to recruit centrally first then rotate. How much rotation you do will depend on what you are trying to achieve. Get some coaching from a good personal trainer, S&C coach, or physiotherapist.

BRIDGING & MODIFIED VERSIONS

Bridging type exercises isolate your posterior chain: deep back muscles, glutes, hamstrings and calves. Often people are more dominant in their calves/hamstrings, or lower back, and weak in their glutes. Bridging where hamstrings are emphasised, such as, heels on a box/bench or in suspension straps, are excellent training for heel hooking and being strong in rock overs. Strong hamstrings protect your knees. For the purpose of this article we will talk about bridging for core.

BALL BRIDGE head and shoulders on ball: this type of bridge isolates glutes a bit more than hamstrings. The floor version tends to recruit hamstrings a bit more than glutes.

FLOOR SINGLE LEG BRIDGE with added anterior oblique sling recruitment: good for lower back pelvic girdle strength. Can do static holds and/or hip lifts with holding the tension in your hand/inner thigh. Do not do if you have Sacroiliac Joint pain or sciatica. See a health professional if you do.

SIDE PLANK & MODIFIED VERSIONS

Side Planks isolate your torso: obliques, rib cage muscles, quad lumborum, deep hip and shin muscles AKA lateral chain muscles.

When preforming Side Planks, ensure ribs and hips are both lifted up so that nose, navel and pelvis are all aligned.

BENT ARM SIDE PLANK with long legs: long lever legs is an intermediate difficulty, you can make it easier by bending your legs. By having your arm bent this isolates your shoulder and torso more than your arm muscles.

BENT ARM SIDE PLANK with legs in straps (very difficult). Start with easier versions. Straps and cushions add instability to make it more difficult.

Adding a straight arm lengthens the lever that the torso and shoulder need to work against, as well as adding elbow stability. You should start new variations always in a short lever position (bent arm or bent legs) first, before moving onto a long lever version (straight arm or straight legs). You want to be strong from the centre outwards, not the opposite.

FRONT PLANK & MODIFIED VERSIONS

Front Planks isolate your anterior chain muscles: deep abdominals, deep chest and rib cage muscles, hip flexors and rotators, as well as, front shins.

FLOOR FRONT PLANK: demo is with long levers (straight arm straight legs)

LONG LEVER FRONT PLANK WITH ARM LIFT: best to start variations with a bent arm first to establish centre/core strength (torso/shoulders) before adding arm and elbow stability. The arm lift adds shoulder blade strength, which is part of our centre/core

LONG LEVER FRONT PLANK WITH LEG LIFT: the leg and arm lift helps to recruit hip and shoulder muscles that are a part of our "core" and also add an element of instability.

FRONT PLANK HANDS IN STRAPS & FEET ON BALL: this exercise is really hard!! I have skipped a few steps here, just to show you an advanced version, and to highlight how you can make these exercises harder. You should obviously start feet on a box or something more stable, before progressing yourself onto a surface that is wobbly.

SUPERMAN & MODIFIED VERSIONS

Superman type exercises isolate oblique chains which help to join our limbs to our torso and hips. Oblique chains work to compress our lower backs, hips and pelvic joints.

With all superman type exercises, if the arm is straight DO NOT lock out (hyperextend) your elbow. Keep elbow creases facing towards each other and straight, not hyper straight. Training and climbing with hyper straight (over extended) elbows stretches out elbow ligaments and tendons, which will contribute to repetitive strain. It also loads the elbow joint in an unbalanced way, as well as, twists your wrist and shoulder in an unbalanced, off centered position which strains the soft tissue around these joints. You want to work your muscles and tendons in a "co-contracted" way, you do not want stretching and compression of non-contractile soft tissue.

KNEELING FLOOR SUPERMAN

KNEELING ON CUSHION FLOOR SUPERMAN

SUPERMAN ON TOES

LONG LEVER FLOOR SUPERMAN

Examples of exercises that are more CLIMBING SPECIFIC are:

HANGING BACK PLANK:

When hanging it is important to "set" your shoulder blades before moving your arms which means chest up slide blades up and back slightly. You also dig your heels into the floor or surface you are standing or balancing on, then tense the back of your legs and buttock muscles, this is also termed your "posterior chain". This is also "body tension". If you were going to continue the pull and preform a "T" then your shoulder blades also follow the arm movement and squeeze backwards as well, as your shoulder blades need to move in the same direction as your arms.

Take note of your elbow position by looking at the inside creases of your elbows. If you hold the handles palms away from you or thumbs up, then ensure your inner elbow creases are facing inwards/towards each other. This sets the shoulder muscles in the right way. Otherwise you can strain elbows. If you are struggling with "dissociating" your shoulder and elbow rotations (finding it hard to set shoulders and turn elbow creases inwards) then see a therapist as this is an injury risk factor.

HANGING BACK PLANK heels on box:

Using a box to bridge onto. This applies more gravity to your posterior chain and simulates tension needed for steep climbing.

HANGING BACK PLANK heels on ball:

Using a fit ball to bridge onto. This adds more of a stability component to the exercise.

SIDE PLANK WITH ROTATION:

Climbing involves a lot of torso rotation so it is really helpful to train rotation into your core sessions. This can be added to any of the basic core exercises.

With weight, or not, on floor:

LOWER ABDOMINAL STRENGTHENING IN HANGING

Here are some variations that train your core but are abdominal focused. They are variations of L hangs, which are very climbing specific. If you grip something narrow and comfortable, you can focus more on the core/abdominal component, if you hold onto a finger board then obviously you are training forearms and elbows more with your core/abdomen. You choose according to your strength goals and abilities. If you are training power then choose something that you can do 1-4 x with a warm up, power endurance then 5-12 reps, endurance 13-20 reps. 3 sets of each is adequate. For best results you can include these in a strength and conditioning, or antagonist training day when you are fresh. You can also do core and/or abdominal strengthening after a climbing session but you may not perform as well as if you were fresh.

TECHNIQUE:

Like with all of these exercises, you want to think about your deepest pelvic layer even before you hold on, or move, so you imagine you are gently pretending to "stop your wee" to engage your pelvic floor, and gently pull your lower belly, under your navel, up and in. You then lift a leg or legs, tuck your pelvis under if lifting past 90 degrees of hip bend, and then if you are continuing on to moving your torso, think about gently exhaling your ribs down gently to continue the movement.

BENT LEG L HANG:

This is the short lever L hang, so easiest to start with. You can hang placing your hands in different positions. The easiest being arms to your side, palms facing inwards, as in the demo photo (2 parallel scaffolding poles), or palms facing your face on a pull up bar (supinated grip), and harder still, palms facing away from your face on a pull up bar (pronated grip). You can start with lifting one leg at a time while maintaining tension in the other leg, especially when progressing this exercise to a straight leg (long lever) L hang.

LONG LEVER L HANG PAST 90:

This is much more advanced than the bent leg L hang, as mentioned previously, you can progress the tucked bent leg to a single straight leg with the other one bent close in then further and further out until straight. Just make sure you are doing even sets, reps and holds either side. With the long lever L hang engaging the deepest layer first is important, so pelvic floor, lower abb suck and pelvic tuck, and then allowing your ribs to gently depress as well, almost into a shallow "C" shape.

KNEE TO OPPOSITE CHEST L HANG:

This exercise is the starting foundation to the next one listed. Again, you start short lever, one limb at a time to make it easier. Same recruitment as described for the others. You can vary hand positions to make it easier or harder.

HANG WITH LOWER ROTATION (AKA Windscreen Wipers):

This is difficult but good! Same rules apply for this as for others. You press your arms towards your legs as you perform the leg and lower torso rotation.

Gimme Kraft training book is an excellent book highlighting good climbing specific core exercises. Suspended slings and body weight exercises will recruit muscles needed in climbing. The suspended straps can add an element of instability, therefore, train your core and inner reflexive layer more.

If you would like to contact Nina Leonfellner about having your core assessed or if you want to book an appointment, please see her website.

To find out more about Robin O'Leary please visit his website and Facebook page.

- VIDEO: ROCUPtv - Footwork - Applying Pressure and Heel Positions 17 Apr, 2020

- VIDEO: ROCUPtv - Technique: Footwork Precision and Accuracy 2 Apr, 2020

- VIDEO: ROCUPtv - Technique: How important is good climbing footwear? 25 Mar, 2020

- Injury Management and Prevention: Fingers 27 Apr, 2014

- Injury Management and Prevention: Junior Climbers 9 Apr, 2014

- Injury Management and Prevention: Elbows 20 Feb, 2014

- Injury Management and Prevention: Shoulders 12 Feb, 2014

Comments