A personal account of exploratory alpine climbing in Greenland over July/August 2016. David Barlow, Geoff Hornby, Robert Powell and Paul Seabrook were climbing in the Renland Peninsula for a month and established four new routes including the first ascents of two peaks.

It’s January 7th 2016 when a grenade goes off in my email inbox. It’s the post-Christmas / New Year climbing doldrums and I’m sat at work thinking about an ice climbing trip to the Écrins, when Geoff pulls out the pin and lobs email, text and voicemail at me all on the same day…

Can I commit to a trip to Greenland this summer? Can I commit quickly? Can I commit now!?

I’ve said it before, but Geoff is one of life’s genuine explorers: he and his partner Susie have quietly travelled to and climbed in places you will eventually get to hear about when they sit down and write their memoirs, or the relevant guidebooks and Geoff has a ‘little black book’ of places to go and things to climb or explore from which, just occasionally, he shares a secret. This sounded like one of those times.

He’d introduced me to the Moroccan Anti-Atlas’ trad climbing potential before most had heard of Tafraoute. He had done loads of new routes there – so we went together and did some more, and as many of you now know, it’s great. He’d introduced me to Norway’s Setesdal Valley ice climbing, and wrote the guidebook, have you been yet? We went and did some new routes there, it’s great, just don’t expect access paths, bolted belays or hooked out routes! He’d introduced me to...well, you get the picture.

So, in the spirit of 21st century exploration, a trip to an almost unexplored glacier system in the Renland region of east Greenland, to climb new routes, alpine style seemed a perfect way to break out of the winter blues – I said yes – and started the negotiations required to free up the time from work and family. To my surprise, everyone thought me going off-grid and into the unknown for 5 weeks was a great idea, “once in a lifetime opportunity” was said several times. Perhaps their analysis was that I wouldn’t come back!

Fast forward several months and our team of 4 (Geoff, David, Robert and I) are sat, whiskies in hands, around a table reviewing the information we have on the region. The now famous Mirror Wall, whilst close in real terms, is in another glacier valley 15km by helicopter away from our target. An American couple had visited ‘our glacier’ in 2012, we had their AAC report and a handful of photos. They had explored the glacier valleys and done some exploratory climbing, but had retreated from their main objective citing lack of abseil tape: so we resolved to take extra! We also had a few photos from Kenton Cool who had visited in 2013 with clients, again mainly exploring the glaciers and judging from the photos had scrambled/climbed up to at least one high ridgeline. But largely the entire 8km valley system with alpine scale rock walls and peaks surrounding it and many feeder glaciers was completely unclimbed – imagine the Mer-de-Glace before the golden age of alpinism – everything to play for!

Interesting peaks were pawed over and potential lines were picked out from the photos, we tried to work out exactly where each of the photos had been taken to help us better understand the territory. Google Earth gave us additional insight, and possible objectives were identified but, needless to say, and to mis-quote from history, “no plan survives contact with the enemy”. Our plan was no exception.

In-country logistics were organised by Tangent Expeditions. Paul Walker has an operations base at Constable Point and would facilitate our shipping, transportation, communications, polar bear kit, guns etc. All we needed to do was pack everything we needed for a month and then move it all into place once we were dropped at the end of the glacier – and go climbing. Tangent had done the Mirror Wall logistics for Berghaus/Leo Houlding, and knows the region very well, having operated there winter and summer for over 20 years. Our budget, in both cash and tonnage terms, was more modest than theirs so, rather than their helicopter delivery, we were going to be transported by RIBs for the 200km sea transfer from the dirt landing strip at Constable Point to the glacier – 12 to 14 hours in two small inflatable RIBs, each way, at night, oh joy of joys!

Fast forward again to July 21st and we’re stood on the gritty beach at the end of the glacier valley, at the edge of the world, dressed in a 14mm thick neoprene survival suit and sweating in the midday heat – it’s 71° North in the Arctic circle, but it's summer, 24hr daylight, it's hot, and the survival suit is keeping the mosquitos at bay, just. That evening, having set up a basecamp a couple of hundred metres from the shore, I counted 25 mosquito bites just on the back of my left hand – I would have preferred polar bears I think.

Our plan was flexible, but initially we wanted to explore further into the range and perhaps establish a higher Advanced Base Camp (ABC) from which to operate, only returning to the coast to rest, refuel and resupply for the next route. The first part of the glacier was a straight 4km to a 90 degree left turn, where a subsidiary glacier junction and icefall signalled the start of the difficulties. Our thought was to find somewhere to set up a higher camp at this point. An added benefit was that the satellite images on Google Earth showed the shadow of a large peak we’d nicknamed the Dru on the inside curve of this bend and we all had plans for that peak. There followed several days of load carrying up the glacier, over moraines & boulder fields to a small glacier lake & gravel-flat we chose for our ABC. Unfortunately it was during this phase that Geoff took a tumbling fall through a snow patch and badly twisted his knee, aggravating an old injury and ending his trip before it had really begun – a cruel blow, especially as he had done a significant majority of the planning and organisation.

Whilst Geoff waited for his extraction we continued to supply the ABC and explore the upper reaches of the glacier beyond the bend.

There were several inviting walls we had observed from the photos and on which we thought we might do some warm up routes, thinking they were perhaps 250-300m in height. As we got closer and closer we realised our planning needed a rethink as these walls were 900m-1000m tall and definitely ‘big wall’ territory, and whilst we had one portaledge down at the coast we didn’t have static ropes to equip something of that scale – one for the future then…We did use our time this far up the glacier to good effect though, choosing a continuous crack/corner feature from a selection of other possibilities on a subsidiary wall and putting up a 10 pitch E2 5b 420m “Arctic Monkeys” in an 18 hour push tent to tent.

Returning to the coast for a bit of R&R we were pleased to find that Geoff’s wait for a lift was over. He’d left us a note saying that he was on his way home, having been collected by Inuit locals. We were also pleased that the plague of mosquitos was gradually dying off, and that the sea, whilst cold, was still suitable for a refreshing dip despite the icebergs in the vicinity!

So, the pattern was established, rest at the coast, head up to ABC at the glacier junction, climb something in a continuous push using the 24hr daylight, crash at ABC, return to coast, repeat till exhausted: that’s pretty much what we did for the remainder of the month.

Next on the agenda was the unclimbed peak our American contacts had attempted on their trip in 2012. They had offered the name Cerro Castillito and it was easy to see why, the peak having substantial ridges and castellation on its upper slopes. We approached the peak, as they had done, up the west facing glacier and 600m couloir above, to the col on the ridge overlooking the adjacent sound/fjord. From there we climbed the ridge for 650m, the three of us alternating leads, bypassing various gendarmes and other obstacles at AD+/D- until a short abseil and re-ascent landed us on the very pointed summit blocks of the peak. We had seen some old tape abseil stations on our way up, but these only progressed so far, beyond that we were clearly on virgin territory. Our descent along the ridge by abseil was long and slow, taking care to clear loose blocks where necessary and slightly hampered by light snowfall during the night-time hours, although it didn’t get dark because of the arctic summer season. Just as well because this 1300m route took the best part of 23 hours tent to tent, and I for one was pretty exhausted and thankful for a bit of extra ’buddy checks’ from my mates when rigging the abseils. “There’s no I in TEAM!” was our motivational phrase of the day.

Having ticked off Cerro Castillito, one of our planned objectives, our attentions now turned to the major peak on the inside bend of the glacier. In our whisky fuelled planning sessions, each two man team had identified this peak as an objective, and we had drawn virtual lines all over it, however, we were now a three man team, the peak was twice as big as we’d thought, there was water streaking down the approach ramps on the lower part of the NE face, and it all looked very hard indeed – so we needed to re-evaluate our plan again. Various suggestions were discussed, binoculars and cameras were deployed to scope out the possible lines, and eventually a new plan was hatched. The key line was the long arête on the NE corner, but the approach ramps and slabs on the lower section were wet and rotten. An alternative approach was reviewed, using the couloir to the NW as an entry point and cutting back left along broken ledges onto the NE arête. However, even using this alternative approach we could see that we would need to bivi high on the route, and also that we should have a well-developed descent plan because coming back down the route of ascent would not be practical.

We felt that a traverse of the peak was the best approach, up the impressive NE Arete, over the summit, then abseiling from the summit to the col at the top of the NW Couloir and then abseiling the couloir back to the start point and the glacier. To make this safer and quicker we decided to climb the whole of the NW couloir as a route in its own right and equip it with abalakov anchors as preparation for the descent. So that’s what we did, climbing “The Double 00 Couloir” 800m AD giving lots of calf screaming 55° to 75° glacier/water-ice climbing and going on forever! Still, it was for our speed and safety on the subsequent route, so all in a good cause, “No Pain - No Gain!” was our motivational phrase of the day.

Having suffered somewhat in our ascent and descent of the icy Couloir we needed to recharge our batteries, so returned to the coastal camp for a few days’ rest, washing, eating and swimming whilst maintaining a constant lookout for the much spoken-of polar bears, but they never did show up. Occasionally we would see a seal, or a family of ducks, and on two occasions a yacht in the distance, but very little is living up there, so in the end there was nothing for it – we had to go and climb ‘the big one’.

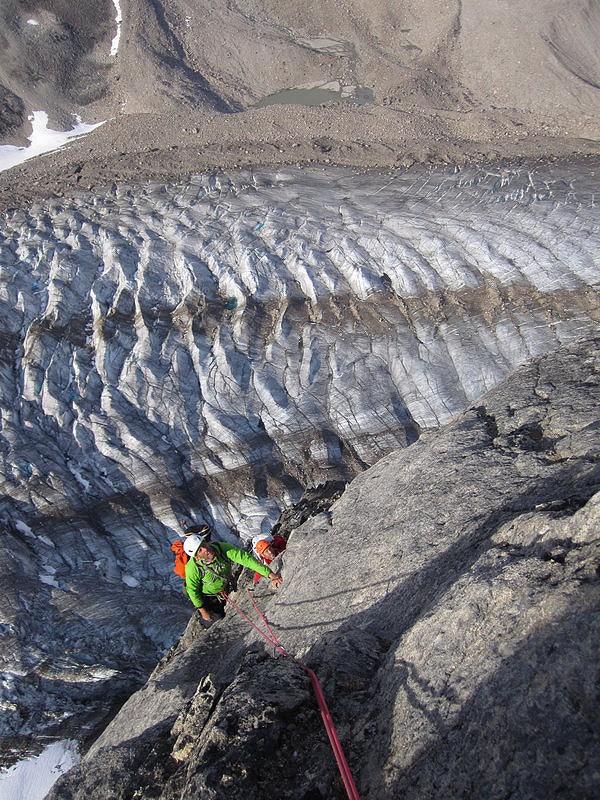

After a careful sort through and repack of the gear we headed out of ABC, up the true left bank of the glacier and through the icefall one more time. Once above the icefall we followed our previous track across the glacier to the start of the couloir and again climbed the first section of this until level with the leftwards rising ledges and ramps we had observed previously, crossing these for 4-5 pitches across very broken ground we reached the NE Arête at a level above the first detached tower, and the climbing proper could begin. We had taken bivi gear and food but no stove, and wanted to get as high as possible on the route before stopping for a rest, so we hoped to climb quickly and efficiently. Typically the approach on all these routes was for the leader to climb the pitch and then both seconds to simul-climb together, and this was our approach here too, however because of the longer route we were each carrying additional gear and all were climbing with a rucksack. Making quick route finding decisions was also essential, and the preparatory work done to scope out a likely line meant we were able to move pretty efficiently despite the complexity of the terrain. We had identified various key features or milestones from our camp, and this was very useful in helping keep track of where we were on the arête and therefore estimate how long before we would get to the likely bivi spot. The quality of rock was also quite varied, sometimes excellent yellow granite, up corners, flakes & slabs, sometimes degenerating into brown “Granola Granite”.

We each lead in rotation, and we each had excellent pitches that we didn’t want to end and horror pitches that seemed like they would never end. Eventually, after approximately 13 hours of climbing we reached a suitable ledge right on the arête and settled in for the night, watching the partial sunset at midnight /sunrise at 0100 and both in an almost Northerly direction – weird.

I don’t think I slept, but apparently I snored anyway!

Starting again soon after 7am, we continued up the arête in a spectacular position, gradually able to see further into the range as we gained height relative to the peaks around us. Rob lead up a great corner system and Dave took us up around a series of ribs and grooves on the arête to the left and onto the east face. Pitch after pitch continued until eventually we hit the summit ridge and by 13.45 the summit. Rob had suggested we name the mountain after his friend who was killed in the alps recently, so we take a few photos of ourselves with a card written to Hannes’ parents and call it Mount Hannes.

Given the thought and effort we had put into preparation of the descent we were hopeful of a quick afternoon’s effort to make it back to the glacier, but, once again, the plan needed more work. Initially we needed to get off the summit ridge and onto the col, and we knew we would have to descend unknown ground over very steep rock to do so. Rob did a magnificent job rigging and negotiating five 50 metre abs, several with hanging stances, before we made it to the ice about 25m below the col. Putting my crampons on, mid descent, on a hanging stance is a trick I will remember for a long time, but at least all the abalakov belays in the couloir below us were in position, so once we reach them we were home free - right? WRONG! As Rob reaches the first set of threads he shouts up – they’d melted.

Disaster! – we had rigged them double, so that we could pull our ropes and still re use them – we knew we’d be back, so how had the tapes melted?

No – not the tapes – it was the ice! Despite digging deep to good ice, despite rigging two equalised tapes, despite the fact it’s a North facing couloir, despite the fact it’s in the arctic, despite despite despite…Over the 5 days since we’d set them the ice had melted out around the tapes and they were all useless – we’d have to set them all up again! Delay leads to danger - during the long descent there is at least one very close call with rock-fall in the couloir. We’re probably half way down, and being last man I have cleared the backup ice-screw belay and I’m descending on the ab rope when we hear crashes from high above, there’s a cluster of smaller breeze block sized debris, but one larger block hurtling down the couloir towards us. At the last half-second I guess which way the rock will ricochet as it approaches and run horizontally across the ice to pendulum out of its way. At least I was mobile; Rob and Dave were strapped into the next belay down and could only duck as the blocks flew over their heads. A close call. A long way from anywhere.

40 hours after starting out we’re back at ABC, wasted, and ready for a long sleep. The nights are starting to get more obvious but we’re a bit time shifted and feel almost jetlagged. “Polar Daze” seems an appropriate name, a play on ‘days’, which also reflects how we feel. Alpine TD-/TD, 1400 metres climbing, 20 pitches to E2 5b.

It’s time to go, we’re all a bit climbed out, so spend the remaining time clearing the high camp of any trace of our visit and then exploring the near coastline, bouldering, playing on a slackline, photographing or just chilling before the boat comes to start the long long journey home.

Wrap up & Thanks

The team were grateful for the support of:

Mount Everest Foundation – full report & route topos submitted

BMC – full report & route topos submitted

Alpine Club Montane Climbing Fund – full report & route topos submitted

Comments