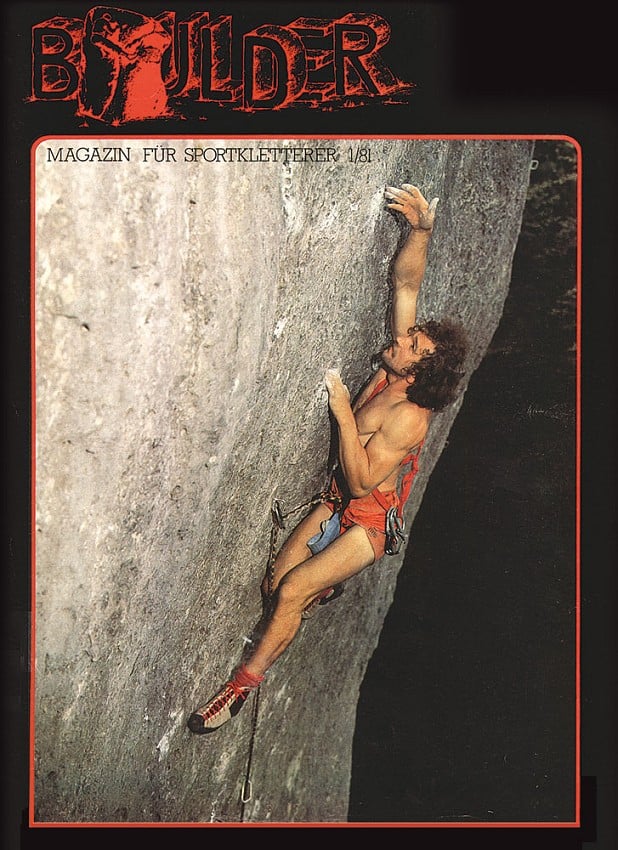

Andrew Hannan shares the first chapter from his manuscript about the history of free climbing, introduces us to Kurt Albert, and explains how the redpoint came to be.

Chapter One: Coffee and Giants

There are pivotal moments in history which can be so clearly defined that they appear to be a single point of light at the convergence of two cones. One cone comes from the past, gathering isolated ideas and deeds, until all are fully focussed on this single point. It becomes both a logical conclusion of the foregoing and, simultaneously, an ignition spark for the future. The second cone radiates forwards, increasing in volume, momentum, and in the diversity of what following generations will make of this unique instant of the bundling of the rays.

The 22 year old climber sitting at the scruffy kitchen table of his shared climbers' flat in Nuremberg had no such thoughts. He needed a coffee. Everybody knew that Kurt Albert was in constant need of coffee. Years later he would be sitting with his friend Wolfgang Güllich and a few other climbers in the university canteen in Erlangen, taking part in a discussion with Wolfgang's professor of sport science. The professor would be chastising them for their ignorance of the importance of hydration in sport: the climbers, with their enormous daily training volumes, were not drinking nearly enough liquid. Kurt's disarming reply would be: 'But however hard you try, it's impossible to drink more than three litres of coffee a day!' The discussion would dissolve into laughter, and Wolfgang would later formulate his well-known thesis that 'you don't go for a coffee after climbing. Drinking coffee is an integral part of climbing'. On this spring morning in 1975, Kurt started to assemble a substantial breakfast, put the kettle on to boil, and took a pack of his favourite brand down from the cupboard.

Isaac Newton, a man not unfamiliar with the behaviour of focused and dispersed light rays, wrote in a letter to fellow scientist Robert Hooke: 'If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants'. It is very possible that Kurt would have recognized this quote; besides being one of the strongest climbers of his generation, he was also a gifted mathematician with catholic reading tastes.

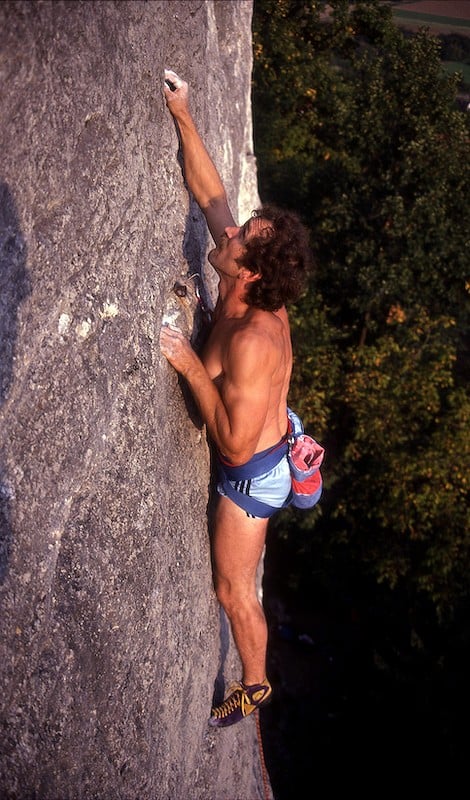

He was a bit of a giant himself, six feet tall and very powerfully built, and he certainly knew of the climbing giants who had preceded him in the hundred or so years during which rock climbing (as opposed to alpinism) as a sport in itself had been practised. He had his clear favourites among these giants: the pioneers of free climbing. Free climbing is the purest form of roped climbing; protection is used solely to prevent dangerous falls, and certainly not as an alternative means of sneaking past the difficult bits. In the West Germany of 1975 it was practised by very few and frowned upon by the all-powerful Alpenverein (Alpine Club), who kept a strict eye upon the antics of its young hopefuls. The wild-haired coffee drinker sitting at the table was fascinated by the new possibilities which free climbing offered, and he and his friends had been busily and joyfully needling the Alpenverein.

Rock climbing in nearly the whole of mainland Europe at this time included aid moves as a matter of course. It was considered completely legitimate to pull on the odd peg or two, either directly or by using tension from a threaded tail of rope. Etriers were carried for use on sections of routes which were considered to be otherwise unclimbable. The best young climbers, of whom Kurt was one, were capable of ascending many of these without using any aid and, what was worse, they regularly underscored their superior climbing skills by removing fixed pitons.

The Alpenverein was up in arms about this supposed desecration of their traditional routes, but that didn't particularly bother Kurt and his friends. Their favourite deceased giants, with their hemp ropes knotted hopefully around their waists and their felt or rope-soled shoes sliding around on their feet, had put up incredibly bold and difficult free climbs in the first decades of the 20th century. Their names included Oliver Perry Smith and Rudolf Fehrmann, from the Saxon sandstone towers which cluster along the river Elbe not far from Dresden; Paul Preuss from the Northern Alps of Austria, and Giuani Vinatzer from the Italian Dolomites; all of them had been supreme masters of their craft and dedicated pioneers of the free climbing ethic.

Scattered seemingly randomly about the globe in 1975 were other areas with fierce free climbing traditions – the gritstone crags of the English moors, Fontainebleau with its unique sandstone boulders, the Shawangunks in the Appalachians – but in an age with little readily available information Kurt did not yet know this. Nevertheless, he and his friends had already travelled several times to East Germany to climb on the Saxon sandstone, and in doing so had experienced the intense satisfaction which is produced by overcoming a climbing problem solely through the pitting of your own brain cells and muscles against the rock. Free climbing had become their passion and, back home, route after previously aided route was succumbing to their impressive climbing ability.

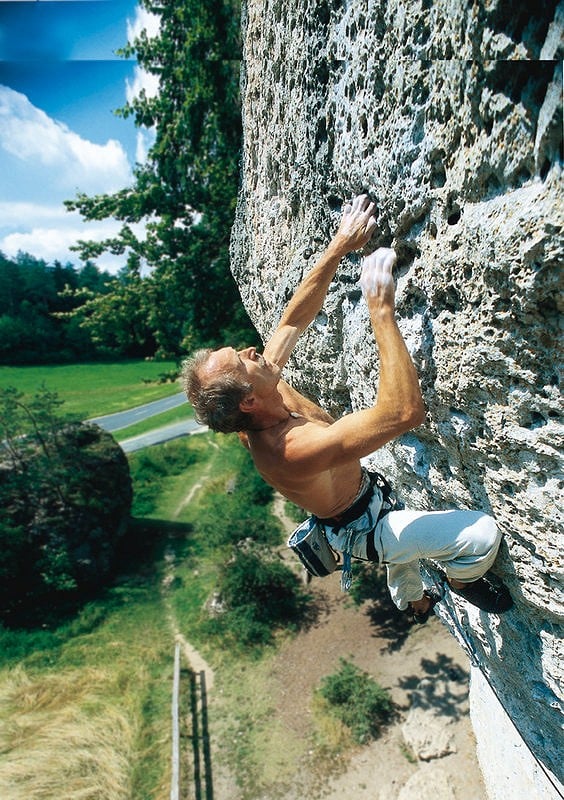

The Frankenjura lies in Bavaria in southern Germany and is, together with the Elbe sandstone in Saxony, one of the two most important and historic climbing areas in Germany. More than 1000 towers and walls consisting of the finest compact limestone are strewn over several thousand square kilometres; many are hidden deep in the woods, others lean gently over lush meadows next to winding country roads, and yet others tower blatantly, hanging their huge and intimidating roofs out to dry over the centres of impeccably picturesque villages.

There are shaded routes next to streams for the heat of summer, and windproof suntraps for winter days; the Franconian wines and cuisine are justly renowned, and the density of cafés, campsites and breweries is high. There is enough climbing here for several lifetimes; to date, over 13,000 routes allow climbers of all preferences and abilities to take their pick between slabs, walls, overhangs, roofs, cracks of all widths, and any desired combination of all these. The Franconian speciality is also sure to be encountered in one form or another on nearly every route: the pocket.

These water-eroded holes in the rock will accommodate anything between the tip of the first joint of Alex Megos' little finger to the blindly groping hand of a novice in extremis. They are always welcome, not infrequently glorious, but also regularly painful on a scale ranging from mildly uncomfortable to outright excruciating. Climbing in the Frankenjura without having used a pocket would be as unthinkable as a day spent on gritstone without having trodden in the sheep shit. Kurt had the good fortune to have this enormous climbers' paradise for his daily play - and battleground.

He finished his coffee and opened his rucksack. Nothing to check: he hadn't bothered to unpack yesterday, and the familiar and curiously heady odour of well-used slings and rock boots rose to greet him as he added some food, a water bottle, and two new and slightly incongruous items: a tin of bright red gloss paint, together with a small paintbrush. He had had an idea, and today he was going to put it into practice.

He drove to Streitberg in the Wisent valley and met his friends; their destination was the huge shield of rock which flaunts itself on a hill high above the village – the Streitberger Schild. Not the huge and highly visible south face; they headed for the slightly shorter and narrower west face, tucked away around the side. Here there was a hard traditional route, put up in memory of a local alpinist after his fatal climbing accident: the Adolf-Rott-Gedächtnis-Weg. The route had a magnetic attraction for Kurt and his friends. Firstly, it was one of the harder routes in the area at V+/A1 (about HVS/A1), and secondly and more importantly: it contained a couple of points of aid. These, in their opinion, had got to go.

Kurt led off at the bottom right hand corner of the wall. The first half of the route trended awkwardly left on polished holds up the face, until the meat of the route was reached: a steep, strenuous and exposed crack, from which the rusty eyes of several old pitons blearily winked. Kurt fought hard, and gleefully succeeded in finishing the climb without having had to pull on anything other than solid Frankenjura limestone. Another scalp for his collection, he thought; but there was still a job left to do. After abseiling back down, he opened his tin of red paint. Accompanied by applause and laughter, he ceremoniously adorned the rock at the base of the climb with a simple red circle, about the size of the top of a beer glass. He didn't know it, but he had just banged in the first rung of the ladder which would lead him to gianthood.

A few more routes, then back to the flat. Time for a coffee. He filled the kettle, heaped coffee into the filter funnel, poured boiling water over it, pushed the remnants of his breakfast to one side, put the half empty pack back on the table, sat down, and waited contentedly for the coffee to brew. He'd had a good day's climbing, and he was also pleased with his idea of the red circle: it was simple and cheap to execute, was unlikely seriously to offend any sensibilities at the Alpenverein, and maybe it would make other climbers at first curious and then ambitious to follow suit. Maybe it would even catch on.

It's funny where you get your ideas, he thought, and grinned. From the side of the packet of coffee, the logo grinned back at him. A bright red circle, directly beneath the brand name: Rotpunkt. His favourite sort. The coffee was ready.

Comments

Hi Andrew, great to see this. What a story!

Mick

Thank you Mick, and thanks for your support while writing! ;)

Brilliant!

Good job he wasn't a Nescafe guy. :)

I once climbed one of his 1978 VI+ (F6a) routes at Streitberger Schild. It was frighteningly run-out and hard. I wish I'd known then his first "rotpunkt" was just around the corner from it. One to go back for I guess...

Yes, Kurt’s grading was merciless. One of the Berlin climbing walls has a route which was actually set by him some 20 years ago; when they moved to a new location they recreated the route, using the original structured panels and holds. It’s called, fittingly enough, “Kurt Albert”, and is horribly hard, requiring very delicate and complicated footwork and disproportionately strong fingers. It still carries the grade of VII+ which Kurt gave it (ca. 6b+/6c), but the general consensus is that VIII-/VIII (6c+/7a) would be more appropriate. It’s still on my list, I must have failed on it at least 20 times so far.