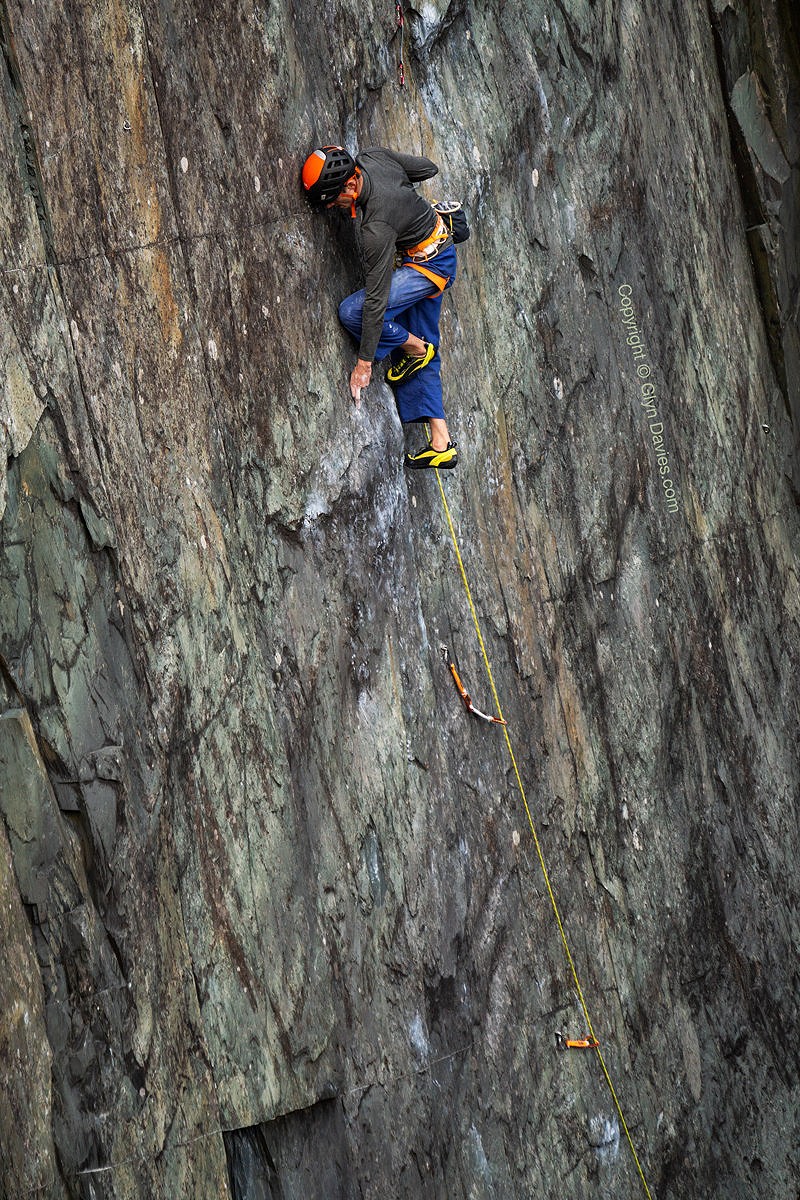

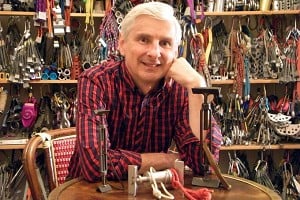

E10 climber Franco Cookson shares his top tips for hitting double 'E' figures.

One of the things people ask me most frequently is how to progress through the trad grades. Let's face it, the main reason most of us climb is for bragging rights. The sense of satisfaction achieved by climbing that next grade up on our beloved British grading scale is unlike any other.

At the zenith of this magnificent system is the mythical grade of E10, and beyond, the unconfirmed world of E11. As we all know, the best climber is the one ticking the hardest routes and with a few small tweaks to your climbing, you too could be topping out on one of the 'biggies'.

For many years, E9 represented the ceiling of British grading, with routes like The Indian Face made immortal through the harrowing accounts of '80s ledge-shufflers like Johnny Dawes. These days things have moved on somewhat: E9s are now ten-a-penny and what most people are really after is that big fat double digit.

After years of coaching beginner trad climbers such as Robbie Phillips, I thought it was time to put much of what I've learned into one place. So, here we have it: what you need to be able to climb E10.

Learn to fall

Falling can be really dangerous, but it can also be really fun. Some of the best days out are those taking huge wingers, hitting the ground and then realising you're OK. It gives you a sense of excitement and a lot of perspective on the rest of your life. Some aspects of falling are of course out of our control and tiny unforeseen factors can result in catastrophic accidents – this is what makes falling off so scary. Even on a sport climb or boulder problem, there is always a risk when falling. There are vectors of movement and external agents that are difficult to predict.

Practising falling of course has its own issues, as in order to do so, you are already falling off. The best method is to build up to larger falls, practising how to safely fall off boulder problems first and then progressing to larger and more awkward falls. Falling off can become a bit of a sport in its own right and, on particularly pokey routes, becomes a major team-effort, involving running belayers, spotters for belayers, multiple ropes, screamers, revolver carabiners, different rope thicknesses, crash mats and dynamic catches. The British trad grade is formed by multiplying difficulty by danger, so if you can remove some of the danger from these routes, your path to E10 can become clearer.

Don't Get injured

Hard trad demands a huge range of skills and strengths all put together at once. This is in part what makes it so rewarding, but also so challenging. Being in good physical shape is only one aspect of climbing hard trad. Of course, you need some level of strength to break free from the wallows of E9, but it is strategically safer to ensure you've capitalised on every other tactic before turning to strength training in its most basic form. We all know people who've had to have months out of climbing hard as a result of injury. Don't do it – you can go an awful long way with pretty meagre strength, if you get your technique, endurance, diet and tactics all as sussed as possible.

Learn to self belay

If you're going to get anywhere with hard trad in the UK, you're probably seriously socially maladjusted. You could get lucky and find some similarly odd folk, but you're likely to be climbing on your own a lot. Most people end up bouldering if they are forced to climb on their own and this can be a good way of gaining power and strength, but bouldering does have some differences to trad climbing. Most of all it requires you to access harder moves high up by climbing the entirety of the problem below, which limits the amount of time you're actually pulling on crux holds.

In contrast, by practising new or established climbs on a rope, you can hang in exactly the right position and spend longer on the very hardest move or moves. As you develop your tactics, you can even break moves down into pieces, practising the way you climb into and out of a position. This is known as 'the narrative' of your journey through each hold.

There are countless other advantages to self-belaying. By being able to go and visit your project on your own, you can go exactly when you want to, in shorter time slots and in more marginal conditions (no climbing on wet sandstone though!). You will start to get to grips with the place and feel far more at home on the route – which is really important when it comes to the day of the big lead.

Another massive advantage of self belaying is that it doesn't rely on you falling off rocks and hitting the ground. Bouldering relies on the assumption that you are almost guaranteed to fall and hit the deck. Even if this is a fairly short distance and well padded, lots of people come a-cropper whilst out trying to have some 'safe' fun. If you make sure your belay is solid, the chance of injuring yourself whilst self-belaying is relatively low.

Go for danger

Let's not forget that we're going for the biggest trad grades possible here. Unless you boulder 8C or have the endurance of an African Hunting Dog, you're going to have to work damn hard for your E10 on safe moves. As a rough illustration of this, a bouldery E10 with good gear is likely to have a crux of around 8B these days, whereas if you pick a proper death route, you could probably get by with 7C or V9 – perhaps even easier if the route was more sustained. In addition to this, it's also worth future-proofing your tick. The last thing you want is to put all this effort into working your route, only to see it wane in relative difficulty as standards rise.

If the relative softening of safe routes isn't making sense, just think of an example like the Indian Face. It has barely slipped in terms of relative difficulty since the day it was climbed, whereas safer things like The Big Issue or Impact Day are now getting flashed and are likely to become trade routes whilst their bold historic equivalents are still given a wide berth. Eventually these two groups of climbs will receive significantly different grades.

Pick a real knacky death route if you can. It's also worth bearing in mind that rock climbing is still in its infancy, so you need to try and think about how hard your project is likely to be in 10, 20, or even 100 years' time. You want your E10 for life after all.

One of the reasons why the North York Moors has some of the hardest trad routes anywhere is because the style of the area so ruthlessly exploits the trad grading system. You get relatively little reward in your E grade by routes being sustained, or physical but safe. The point at which the E grade goes exponentially berserk is between that point of significant danger and almost guaranteed serious injury. Even a moderately difficult crux will get a huge price tag if the landing is a pile of rocks and there's no gear.

Play the game: short routes don't feel as scary but can still get you your E10 once you apply the maths – so long as there is that one unprotected bit of hard sketch.

Use your feet

Climbing is just walking that has been tilted. You can stand on your feet for ages, but most people can't hang from their arms for that long. In any vertical or slabby climbing (i.e. most of the UK), using your feet is important, but in trad it is doubly so. Just like when walking up a mountain, your stride length will determine how tired you get. One of the few disadvantages of being very flexible in climbing is that you tend to favour large movements with your feet. These are often sketchy moves and also require much more arm and leg muscle to initiate.

Experiment with using improbably small intermediate footholds on top-rope. Use your outside edges, get some sensitive, pointy shoes. Once mastered, this will save energy and also make you more confident with big footholds. You'll relax more, rest better, sweat less, panic less - win, win, win, win.

More to the point, once you get used to using tiny footholds, you'll look dead good and can happily show off at the crag whilst people talk in hushed tones about your fabled E10 ascents. Your massive heel move or crotch-height toe stab should be the trump card you hold in your back pocket, ready to be pulled out in those moments of extremis.

Find your niche style

As well as seeing bad footholds as one of your strengths, having positive feelings around high feet, gastons, thumb sprags, monos and razor holds will allow you to enjoy routes that other people do not. Everyone climbs better when they enjoy it and remember that all grading systems are subjective. As we're trying to play the grading system here, we're in de facto competition with every other climber on Earth.

If you decide that your forte is pulling on big holds up a Kilterboard, then you're in for quite the competition. If on the other hand you like ratting on a load of back-handed crozzle, up some sketchy-footed Graywacke, you may find that you can climb relatively difficult routes in that style, when judged in comparison to the rest of the E9 cohort. Finding the style that totally suits you is of utmost importance if you're wanting to climb beyond E10.

Practise down-climbing

A massively important skill for onsight climbing which could well save your life. Enjoying down-climbing can also enable routes with fiddly kit to be climbed without a total endurance battle. It's widely accepted these days that an ascent doesn't count unless the gear has been placed on lead.

Hard trad routes often have very difficult-to-place kit. This may be fiddly wires, skyhooks, tricams or blindly-placed runners. Sorting all of these logistics out is tiring. And the last thing you want when blasting into your crux sequence, is to be unnecessarily tired from having had to place all the protection.

A key strategy here is to reverse back to rests or even all the way to the ground. Some routes have been climbed in the past by climbing up to the protection and then deliberately falling off, lowering to the ground and then climbing again with effectively pre-placed gear. It's fair to say that there is a consensus these days that this wouldn't count as a legitimate ascent. If you can't continue to the top after placing the kit, then you need to place it on lead and then return to the ground. Once you've proved you can place that runner on lead, then if you want to pre-place it another day, I don't think that's a huge problem.

Of course for any of this to be possible, you need to really get to grips with practising down-climbs and down-climbing. This is one area that can be practised well whilst out bouldering, as you are generally climbing down easy or moderate ground, prior to a crux. I'd recommend to everyone to do more down climbing, as it introduces a whole host of technical problems that complement normal climbing perfectly, as well as building antagonistic and static strength.

Pick soft routes

This does what it says on the tin: the classic tactic for sport, bouldering, winter climbing or trad. Of course the skill here is in finding soft routes that other people don't know are soft. Finding esoteric locations where not many people are likely to go may work with E7s and E8s, but there are unfortunately still not that many E10s in the UK. If you find somewhere with fickle conditions or big walk ins then this may help, or find a route that everyone who has climbed it has a vested interest in remaining over-graded.

If all else fails...Ballpoint

If at the end of all these decades of training, projecting and dieting, you still don't feel ready for the lead, you can of course just ballpoint the route (the term refers to 'ticking' a route in a guide with a ballpoint pen without having actually climbed it).

It's important to make up a reliable witness (not just some random person you bumped into and have never seen again), or if you're good with computers you can edit a top rope out of your videos. If you're going to go down this path, you really need to be an expert in the realm of meditation and controlling your mind. Remember this is meant to be the highpoint of your whole life, so if you're going to lie about it, you need to be able to convince yourself that you've done it too.

Of course, with that level of determination and delusion, you should probably be able to make it as a top trad climber anyway, so it might be worth having another look at your project after all. Whatever you decide is your truth, make sure you're comfortable with it: the last thing you want is a Lady Macbeth-style breakdown where you're endlessly washing your hands and chanting "Mind Riot" over and over again.

Good luck!

- ARTICLE: My Favourite Route by Franco Cookson - Wombat E1 5b 29 Oct, 2024

- TRIP REPORT: Franco Cookson's Journey to the Mirror Wall 25 Dec, 2023

- OPINION: The Blurry Line - When does a sequence become a line? 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: 2021: The Year of the Headpoint 15 Nov, 2021

- DESTINATION GUIDE: North York Moors Limestone 9 Apr, 2019

- ARTICLE: Franco Cookson's Guide to Headpointing 15 Jan, 2019

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Spittal Crag, Northumberland 16 Oct, 2018

- ARTICLE: Franco Cookson's Guide to Highballing 13 Jun, 2018

- DESTINATION GUIDE: The Yorkshire Coast 16 Apr, 2018

- DESTINATION GUIDE: North York Moors 15 May, 2008

Comments

Genius.

Only a grain away from the truth ;)

Outstanding! 😃

Not only can the guy climb a bit, he's a decent writer as well. More please.

Best article I've read, love it!

Franco should get into coaching, punters like me pay top $ to be showered in such truth nuggets for that quest for the all consuming sweet sweet logbook green tick.