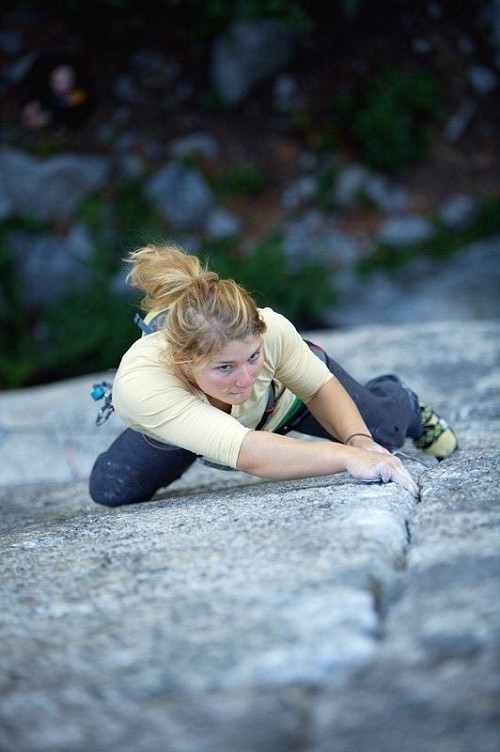

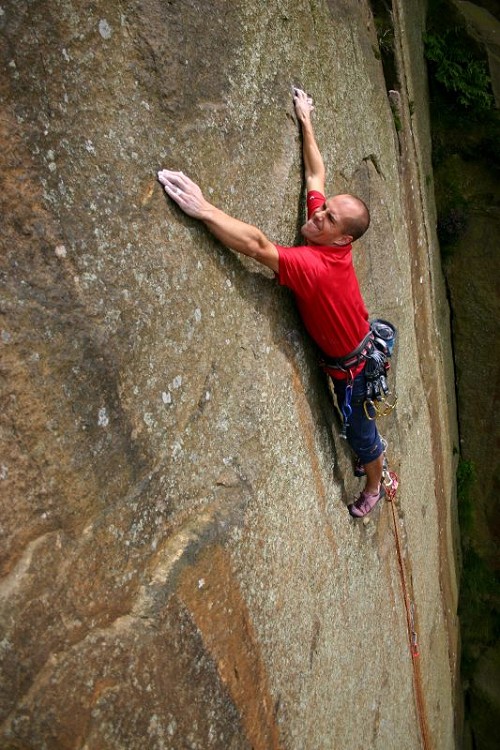

In this article, Hazel Findlay, one of Britain's top climbers, takes an upside down look at succeeding on trad routes - with her top ten reasons for failure.

10 common reasons you fail on a trad route and how to deal with them

Every time I fail on a route, I try to work out what went wrong and how I could possibly remedy it so that given a similar situation in the future, I won't fail again.

Really, these lessons have to be learnt yourself, the hard way. You have to rack up enough failures before you start to see successes. However, when I was growing up there were a number of little snippets of information that my Dad passed over to me that I still remember and still help in a lot of situations. Over the last few years I've tried to do the same with the climbing partners I've had, listening to what they think are the best methods for dealing with rough situations, or how to climb more efficiently, or faster. When I fail and my climbing partner doesn't, I try to see what it is that they did differently, and attempt to replicate it myself.

It's fair to say that I have a number of 'tips' or methods of dealing with certain situations that I try to apply when I'm climbing. Often, when I fall it's because I have failed to put into practice one of these 'tips'. I thought it would be fun to write an article taking the most common reasons why people fall off routes and offer a number of 'tips' or methods with which to apply and therefore hopefully stop these causes of failure happening again in the future.

Things to bear in mind:

1) These are a collection of tips that I have found to be useful; you and your friends might have better ones. However, they are worth a read because you might something you haven't thought of, or you may start to analyse your climbing more and think more clearly about your own response to failure.

2) Although I'm a half decent trad climber, I don't pretend to apply all these tips, at all times, and neither have I come close to mastering them. No matter what your level, there is always something new to learn and different ways of improving your standard.

3) The reasons below are what they say they are... reasons, and reasons are not to be confused with excuses. If you fall off, try to be honest with yourself as to why you failed, in other words don't say that you fell off because the holds were wet when really it was because you spent half an hour fiddling in an unnecessary RP and got pumped out of your mind.

4) This is certainly not an exhaustive list of all the reasons why you might fail on a route, but I had a think, and these seem like the most common.

5) I have done this for trad climbing specifically, but some of these reasons can be applied across the board.

1: I fell because of loose rock

Unless you embrace an entirely fatalistic life-philosophy there are some things you can do to avoid failing due to loose rock. However in some rare cases, there is literally nothing you can do, such as when you put a foot on a hold that looks and seems solid, but when you weight it... off it pops! Let us ignore these cases, and concentrate on the cases where your actions can make a difference.

There are two things to aim for when dealing with loose rock. The most important thing is not having loose rock hit anyone, largely with your belayer and other people at the base of the crag in mind. The other, less important thing is success; if you pull off a rock you might fall and blow the onsight of that all-important pitch (or hurt yourself if the route is potentially dangerous).

So, with these two aims to consider, what tips are there for reducing the risk of loose rock injuring people or stopping success? Firstly: you and your belayer should be wearing a helmet. If you like your belayer it's to protect them, if you don't, it's to protect yourself (given that your life is in their hands). Secondly, you should adapt your climbing style; concentrate on less dynamic movements, careful planning and reading of the rock. Try to pull down on the holds rather than pull out, with the intention of reducing leverage. You should also test holds before you commit to using them.

However, don't just concentrate on your hands; look at what your feet and the rope are doing whilst you're climbing. It's especially important to ensure that your rope doesn't drag across loose rock at the top of the crag, largely because the tops of crags are looser, lower angle, which means that the rope will come into contact with the rock a lot more and you'll also be traversing around more looking for a place to belay. Gear placements can also be affected in loose rock, try to use nuts where possible and watch out for loose blocks and flakes. Throughout the whole experience communication with your belayer (if possible) is very important. Shout 'below' if you do knock something off and in some cases you can advise them as to where is best to stand to avoid the barrage!

2: The holds were wet, or it started to rain

Wet holds or 'it started to rain' are often used more as excuses than actual reasons, but we do live in the UK where rain is usually never far around the corner. I don't have a lot of useful tips for this one, but the one tip I do have is really good, and it's one that can be applied to all these reasons: try your absolute best. If you really want to do a route, then don't let conditions affect you before they have to. More often than not, you can still hold the holds, your feet wont slip, or if rain is on the horizon, you'll probably be at the top before it soaks through your kagool. This may be deluded positive thinking, but... positive thinking can go the longest of ways.

3: My belayer short roped me.

My main response to this is to get a new one (belayer, not rope). However, there are some belayers that bring other benefits to the table, if this is the case; it's down to you to teach your belayer how to belay better.

4: I was pumped because it took ages for me to read the moves/route.

Now we're getting into real climbing reasons. Being able to read moves and spot gear is one of the most defining features of a good onsight trad climber. The best thing to improve your ability to read both moves and gear placements is to climb more, and on varying rock types to maximise your experience of different moves and gear placements. Onsight sport climbing can also push your trad level since you might be willing to climb harder pitches and therefore be forced to read more complex moves. However, you can follow the bolts and usually chalk whilst sport climbing, so more specific tips would be: have 'soft eyes' as Neil Gresham puts it, in other words avoid tunnel vision. Look wide at all the holds and gear that you can see, plan ahead and don't concentrate solely on what's right in front of you. If, after a concerted effort to improve these two things you still fail on routes because of poor route reading, you may actually have to do the dreaded deed and get fitter. If you have beans to spare you can read the route wrong but correct yourself without swimming in lactic acid.

5: I was pumped because of an inability to place, or find good gear.

This may be one of the most common reasons for failure when trad climbing. However the solution is not as simple as 'it will happen less if I become better at placing gear'. The situation is more complex than it looks because there are a lot of things that may or may not be going on.

Firstly, a situation that commonly occurs is that the leader doesn't actually need to place the gear that he or she is so furiously trying to find or get in. If this is true, it's probably because they are scared with the idea of falling a certain distance. Fear of falling is very common. In fact, so many climbers are scared of falling, it's any wonder half of them go climbing at all.

Firstly, you need to gain enough experience to decide when it is safe to fall, and when it is not. Here I am talking about being scared to fall when really a fall would be safe.

The best thing for fear of falling is fall practice. If you are really scared, don't feel embarrassed to start with top rope falls, or even just swinging around on a rope. Climbing in general and hanging in space with air beneath you, is a very unnatural thing for a human to do, therefore you have to force your body and mind to be accustomed to it. Don't feel embarrassed about being scared of falling, because I swear that more than half of the climbing population is. What you should be embarrassed about is a reluctance to do anything about it... That's if, you care enough. Some climbers will accept a fear of falling as part of climbing, do everything to avoid falling and simply get on with it. This is OK if you don't want to push your grade, but progress will be impossible or considerably stagnated if you don't climb at your limit, and climbing at your limit requires a certain comfort with the idea of falling.

The other reason for furiously trying to get gear in that you don't actually need, is having a false belief that the gear you have already placed you will rip out. If it is bad, then you should obviously get more gear in, but if it's good, sometimes you should push on until you find a more restful position from which to place more. The clinch here, is obviously how to know when gear is good or not. This largely comes from experience. However ways to speed up the learning curve are to really look at your leader's gear placements when seconding or to test your gear, safely.

Another reason for why you might be failing due to an inability to place or find gear is that really you're reading the route wrong. Perhaps if you had looked from the ground and seen that there is a ledge just above you with a nice crack just next to it, you wouldn't be wasting your time fiddling in a micro cam mid crux. Try to plan where you think good spots to get gear will be, however try to stay open to other options as well, if you learn something new on-route.

There is also a further point here - beyond simply reading the route better - concerning choice. You can climb the route in an absent minded way putting gear in when you feel a little scared or run out, or you can choose to place the gear at the places you decide to be the best, such as good stances with good gear. This is a more 'proactive' way of climbing, as opposed to 'reactive' and is a way that will largely increase success since you have much more control over your climbing and the situation.

6: I was pumped due to over gripping (presumably because of fear)

It can be quite hard to tell whether you're over gripping or not. I've seen a lot of climbers say that they need to train more because they are getting too pumped, but really if they relaxed they could up their grade without boring themselves down the climbing wall. A helpful way of finding out whether you're over gripping or not, is to top rope or second the same route you just failed on and see if you get as pumped. It's not a full proof test because there are other factors at play, however you can listen to your body and more often than not you can tell whether you're more relaxed or not.

If you discover that you are over gripping due to fear, what can you do to avoid it? Firstly you need to ask yourself why you were scared. Were the reasons rational or not? If they are rational, such as: you'll deck if you fall, then really you need to fix the root of the problem, which is being in danger. Why were you in danger in the first place? And what can you do to avoid it in future? If the reasons are irrational, for example a fear of falling, then you need to assess this (see earlier in the article). However, there are also a few general tips to avoid over gripping. Firstly: take steady deep breaths. Second: try not to panic. If you don't like the situation you're in, try to realise that unnecessary over gripping will only make it worse. Another thing to think about when you start to over grip or panic, is that actually the holds you have are OK, and the foot holds are big enough. Relax into the footholds, and take deep breaths. If you feel like you're in an awkward position, think about making a small change in body position or a small foot movement, in order to improve your situation and ultimately make you more relaxed.

7: I said 'take'

Again this is another one of those reasons that has a number of other possible reasons at the root of it. A lot of these reasons I may have already mentioned, such as a fear of falling or wet holds. However, although we have all said 'take' at some point in our climbing lives, it's worth noting that really this is nothing more than giving up. And – not to sound too much like a boot camp officer – you should tell yourself this every time you do say take.

Of course, if you're dogging a pitch and you want to work out moves or if you just realised your rucksack containing your car keys is just about to get washed away by a wave, or a French man's dog is just about to eat your sandwich, then this is a different story. But if you're on the onsight of a tough trad route or the 'send' of your redpoint, then really there is no excuse. There is nearly always something you can try, even if it's a last ditch slap to an invisible crimp.

If you're a notorious 'taker', then something you should do is to play the no-take game. I tried this after reading the 'Rock Warriors Way' (which is a good read by the way), and found that although I sometimes let myself down and said 'take', I did end up saying it less, and it did pay off since they were times where I would stick an extra move that I wouldn't have done otherwise.

But more importantly, it made me analyse my climbing more, and helped me to see how often I was climbing to my actual limit. This is also a really good game if you have a fear of falling because if you do actually give up saying 'take', then you'll have no choice but to fall. It might be fun to try it with a group of friends, maybe instead of lent, seeing as no one likes giving up beer or chocolate.

8: I had crippling rope drag.

Whilst climbing with my friend Alex in Morocco, I would often complain of hideous rope drag which would cause me to get tired, or go slow. In response to this he would say 'if you encounter rope drag, you should stop placing gear or clipping bolts until it stops'. Since I felt like the rope drag - although caused by runners – was increasing the likelihood of me falling, and we were in Taghia a long way from any semblance of medical attention, I was a little reluctant to heed his advice. Instead, I tried to stop it happening in the first place by being smart about placing gear and extending pieces. It's useful to look for bulges, traverses or moving around an arête or corner. If you come across these things, either choose to place gear elsewhere or extend the piece so that it's in line with the rest of the pieces. Using double ropes makes this easier however, if you don't manage your ropes well, it could end up sand-bagging you more than with a single rope. It's always very satisfying when you look down at a pitch and you have perfectly parallel train-track ropes, if you want to reduce rope drag, aim for that.

9: I was off route/no idea where the route goes

The most obvious tip for this is to really read the guide book description, properly... like every single word and commit it to memory (I'm particularly bad at this). If you suspect the sanity of the author – which, in the UK is not an unfair assumption – it might also be advisable to ask some 'in-the-know' friends for some beta. Also, you should always be looking out for signs of human traffic, such as chalk, boot rubber, cleaner sections of rock, fixed gear or worn out gear placements. However, the best piece of advice I have for this - despite this being something I personally have trouble with - is to appeal to your common sense: look for natural lines of weakness and ask yourself where the most logical line would go. Jack, editor of this site, and a climbing partner of mine, says to himself; "Where would I go if I was making the first ascent of this route" and he thinks that has got him out of some sticky situations.

10: I couldn't physically do the moves.

This is the most legitimate reason of the bunch, because it shows that on the route at that time, there really wasn't anything else you could have done. It also shows you're getting on routes at your limit, which is always good. And there is really only one tip: get stronger, climb more, train, buy a finger board etc. Enjoy!

James McHaffie, Hazel Findlay and Jack Geldard are running a coaching/instructing/teaching weekend in Wales this coming June.

The cost of the weekend is £200 per person and over the course of the weekend they will be looking at all aspects of climbing, with a focus on Trad Climbing.

If you want to improve your climbing, get expert advice and a detailed evaluation of your strengths and weaknesses, and have a really good weekend, why not join them?

- FULL COURSE DETAILS: Jackgeldard.com

Comments