Chris Craggs is now a full time guidebook writer for Rockfax. He has also written articles for Climber Magazine for years, and is now a regular UKC contributor. Here he tells a multitude of strange tales about the extraordinary Devil's Tower in Wyoming.

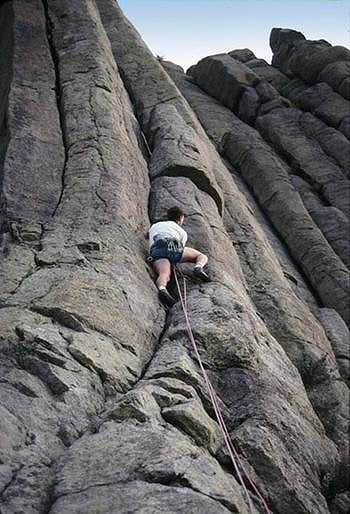

A flash and ear-splitting explosive crack snapped me out of my reverie. I had been half belaying, half daydreaming on a tiny hanging stance one pitch from the top of the west face of The Devil's Tower, Wyoming's best known feature. A couple of hours earlier we had started up Mr Clean (5.11a or E4 5c) one of the most renown routes on the whole remarkable edifice. The crucial pitch had involved a full fifty metres of finger and hand jamming, and boasted a single solitary foothold at one quarter height, it was the most sustained pitch I had ever had the pleasure of following. Graham had disappeared up the narrow chimney above my head when the 'light and sound' show started. Slowly at first then with increasing ferocity it thundered and lightening and hailed and blew. Shorts and T-shirts were not the ideal wear as, doused in icy water, I chilled rapidly then started to shiver uncontrollably. After a sustained period of bellowing up and down the pitch I persuade Graham that discretion was the better part of valour, he abandoned some kit in the depths of the chimney and we beat a sodden retreat. Three long abseils took us back to the scree slopes below the cliff, our waterlogged sacks and soon after that a warming brew at the campsite.

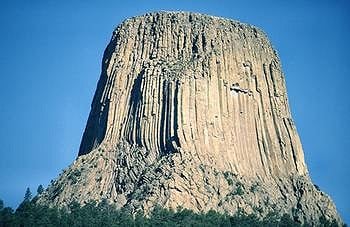

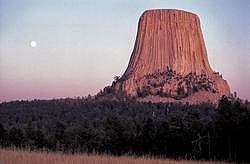

The Tower was the chosen setting of an alien meeting in the film Close Encounters of the Third Kind and if there is a better location beacon anywhere on Earth (its shadow must be visible from space) I don't know where it is. Its summit at 5117 feet rises about 1200 feet above the surrounding plains. It is a climbing destination like no other on the planet, dramatic to the point of being awe-inspiring, and with lines to die for.

We spent the day after the deluge drying out the gear. Looking through binoculars at the tower from the campground it looked strangely deserted. Apparently the mini-epic we had on the west face didn't compare with the life and death struggles on the ever-popular Durrance Route. Here teams climbed over, abseiled past and fought with each other in a manic rush to get off the World's biggest lightening conductor, most climbers had obviously chosen to steer clear for a day or two.

A dawn start the following day was aimed at beating the taboo, I had managed to persuade Sherri this was too good a chance to miss; an early morning ascent of the classic Durrance Route (5.7 or VS 4c). At six a.m. the car park was empty, we self-registered at the deserted Ranger Station and picked our way diagonally across the scree towards the most distinctive feature of the east face; the huge fallen block of the well named Leaning Pillar. The climbing was pleasant in a graunchy gritstone kind of way, up a series of wide cracks and narrow chimneys. The substantial doubled belay rings at each stance ensured an easy retreat if any more pyrotechnics were imminent. A couple of long corners and a short tricky traverse led to a large terrace below the cliff top. After traversing this, one more easy and exposed pitch and we were there, the scrubby summit dome marked by a substantial cairn and remains of an old sign. Apparently in the days when climbing on the tower was banned this use to be located at the top of the scree opposite the Visitor's Centre where it declared 'No Climbing Above This Point'. When the ban was lifted it was transported to the summit where its message became truly unambiguous!

After taking in the view we dutifully filled in the summit register and then slid back down a series of four long abseils and head for camp and a belated breakfast.

Graham was still keen to top out so the next day it was back up the scree below the West Face again. The open lift shaft of El Matador (5.10d or E3 5c) is perhaps the most striking feature on the west face. The crucial main pitch is a soaring chimney, almost three metres wide at the bottom and gradually narrowing as it shoots skyward for forty-five metres. Laybacking the left corner soon becomes a strenuous and exhausting business; at about twenty metres (depending on your height) it becomes possible, as well as essential, to bridge to the opposite corner. Unfortunately relief is short lived and pumped forearms are soon replaced by screaming calves and wincing hips and soon after a superb 'lying-down' stance gives a proper rest. Easier pitches weaved up grooves and corners then scooted through a series of blocky overhangs to the summit. A descent was made back down Mr Clean so we could recover the previously abandoned gear, tidying everything up in a very satisfactory fashion.

A couple of years later I was back again this time in the company of Martin Veale, again a summit trip was a must. Over four days we topped out via McCarthy West Face (5.10b or E2 5b) and McCarthy North Face (5.11a or E3 6a) as well as sampling some of the shorter offerings. Outstanding was the hand crack of Assembly Line (5.9 or HVS 5a), which gobbled up our entire rack of three each of Friends 2.5, 3, 3.5 and 4!

thumb(23436, TRUE, "right") ?>

As to the formation of the tower, the legend goes that a group of young Native American girls was out strolling when they were attacked by a huge grizzly bear. They climbed onto a rock a prayed to the gods and as the rock rose into the sky the enraged bear clawed at the tower leaving the scratch marks that we see today. The truth is only a touch less amazing, 54 million years ago a volcano paused mid-eruption, the lava solidifying in the throat of the main vent. As the rock cooled it shrunk setting up tension within the rock mass which eventually cracked into a Giant's Causeway arrangement of huge pillars. Erosion of the surrounding area exposed the top fifty metres to the weather hence its rather battered appearance. Millions of years later more rapid erosion ripped away the surrounding sedimentary rocks, exposing the rest of the tower and leaving it in all its phallic glory.

Perhaps the most amazing of all the odd feats associated with this cooled volcano's core is the tale of the first ascent. In 1893 two local cowboys (no these were real cowboys) hit upon the idea of building a ladder up the tower when cow-poking was a bit slack. They scanned all the faces looking for suitable sized and oriented crack that would allow them to lean against the wall and wield a hammer. Eventually they located what they were looking for in the centre of the east face. Over a period of six weeks they cut suitable sized staves, carried them up to the tower and set about building their ladder. The staves were hammered and a rail was added and the ladder was pushed upwards for over a hundred metres. As success approached they arranged a party for residents from miles around with their wives laying on the 'vittles'. In non-sticky cowboy boots they soloed the final hairy section and 'Old Glory' was flown on the summit to cheers from the assembled crowds; later it was cut up and sold for 5c a piece – in true American fashion.

thumb(23437, TRUE, "right") ?>

The first 'proper' ascent was in 1937 when some of America's best climbers took on the project. The Weissner Route was the result, a 5.7 (decent VS) classic on which he placed a single per runner on the crux pitch.

Another bizarre incident took place only a couple of years later, in 1941 when local air ace Charles George Hopkins decided to parachute onto the top of the tower to advertise his aerial show. He came prepared with a length of rope, a block and tackle as well as a sharpened axle from a Model T Ford to act as an anchor for his planned escape. His parachute descent went OK but on arrival he found that his rope had disappeared over the edge and he was well and truly stuck! There was only one solution, the first ascensionists were called upon to drive halfway across America to repeat their great feat and bring down the hapless Hopkins who had spent a cold and lonely week on his island in the sky.

The rock is not as you might expect a slippery basalt but quartz monzonite as solid and rough as it gets, and as to the routes being boring, nothing could be further from the truth. There is little in the way of slab climbing (a few quality pitches on the apron below the North West Face) and a sad and solitary sport route here but cracks of every width and corners of every angle abound.

An excellent tarmac footpath runs right around the base of the tower and is a good way of getting an idea of the layout of the place, shooting a whole roll of film off is almost unavoidable.

The place really is unique and as such should be on the agenda of any serious climber, get an encounter pencilled in.

Devil's Tower Factfile

Situated in north east Wyoming prime season is June to September. Recently local Sioux Indians who hold the tower sacred have requested that climbers avoid the tower in June, some Yanks think this an affront to their freedom of religion but surely it is little enough to ask.

It is obligatory to register at the Ranger Station before climbing on the tower, routes that do not go to the top (a large percentage of the climbs) are classified as failed ascents when they add up the tally for the season!! There are several daily demos of 'How the Climbers get up There' (just in case you wondered) on a two metre high concrete monolith in front of the Ranger Station, invariably given by the most gravitationally challenge ranger they have on duty.

There are climbs of all grades from 5.6 (Mild VS) upwards. Generally the climbs are not especially technical but they are incredibly sustained. A large rack of the appropriate sized gear is a must. Quite a percentage of the climbs do not climb the rather crusty final fifty metres but at least one visit to the summit is obligatory so that you can answer in the affirmative when asked by the nth tourist "Did yer make it to the top?"

Guidebook - Rock Climbs on the Devil's Tower by Steve Gardiner and Dick Guillmette lists all the main routes.

There is a pleasant USFS campsite in a bend of the Bellefourch River opposite the East Face.

Comments