Luke Davies shares tips and tactics for climbing the six classic north faces of the European Alps—with some history to boot...

In the 1930s, Alpinism had already been around for over a century and the list of unclimbed faces in the Alps was becoming shorter and shorter. Top Alpinists of the time from Austria and Germany such as Heckmair and Welzenbach were competing with the likes of strong Italians like Cassin, Comici, Gervasutti and the French such as Pierre-Allain and Contamine to climb the last remaining 'unsolved problems', many of which were overcome before the outbreak of WWII.

During this time, Alpinism was going through a development period with ever steeper rock being climbed with the use of pitons and training, all contributing factors to these pioneering climbs. However, many of the attempts still proved deadly and are far cries from the repeats of today with modern gear and techniques. In the 1950s, Gaston Rébuffat, one of France's leading Alpinists devised the list of what he called the 'Six Great North Faces of the Alps' in his book Starlight and Storm, and was the first person to climb all six of what he considered were the greatest faces of the Alps and some of the harder climbs of the time (although there are many other big north faces in the Alps as can be seen in my Grandes Courses article…).

Today, climbing these six routes is still a big undertaking that requires favourable conditions and timing as well as a range of skills on both rock and ice, a healthy approach to suffering and a risk tolerance for bad rock and being strapped to a face for days at a time. However, with the advancement of climbing gear and skills, most can be climbed by experienced climbers rather just being the realm of the total elite. With global warming having a big effect on the Alpine environment, timing conditions has become a major factor with some routes only becoming reasonable every few years or for mere weeks at a time. This, in addition to their infamy, means that when conditions are 'good' they are often very busy – a modern consideration that has to be dealt with. In this article I will outline the logistics for each route, looking at what is needed to climb them and when.

Note: for the purpose of this article, summer climbing gear consists of rock shoes, a single set of cams up to yellow (possibly doubles of commonly used sizes), eight quickdraws, a small set of nuts and a couple of slings per person. Winter climbing gear is this (minus the rock shoes) in addition to six ice screws and an Abalakov threader. Sleeping kit refers to sleeping bag, bivvi bag, roll mat, stove, gas, food etc.

Piz Badile

The Piz Badile (3305m) is a mountain in the Bregaglia range on the border of Switzerland and Italy. Its large NE face drops down on the Swiss side and provides over 800m of steep granite slabs. It was first climbed over three days in July 1937 by the Italian Riccardo Cassin, arguably the best climber of his generation, with Ratti (another prolific Italian of the time) and Esposito. They caught up two other Italians, Valsecchi and Molteni, who were already on the face. However, they both died—one due to exhaustion near the summit and the other on the descent.

The route follows an exposed ledge system out onto the face, where slabby ground leads to ledges at half height. From here the route primarily follows a groove system before entering a large chimney system that leads to the North Ridge not far from the top. The main difficulties are in the groove system off the halfway ledges, but these are well pegged and, in general, the objective dangers of this route are relatively low (for a north face) with solid granite. Being a rock route, it is the one of the easiest routes to find in good condition, on any dry day in the summer months and with its modest difficulties, it is the easiest of the six to climb and a good starting point.

Cassin (TD) Route (Via Cassin)

Grade: TD 6a (HVS/E1)

Length: 800m

Start Point: The Sasc Fura hut or a bivvi above. These are accessed by a long walk from the village of Bondo. The old access to the hut (before the Cengalo rockfall) is still possible if you seek it out, however the new, longer way is signposted.

Conditions: This route is rock-based and so just needs dry conditions, meaning that any dry period between late June and October should be possible.

Gear: Summer rock climbing gear and approach shoes. Early in the season, crampons and axe might be needed to cross the exposed starting ledges.

Topo: Many available online and a good description on Camp2Camp.

Difficulties: The main difficulties here are a couple of pitches in grooves off the halfway ledges; they are well pegged and can be French freed if necessary.

Dangers: Possible snow on the initial ledges – otherwise relatively low objective risk.

Tactics: Being low altitude and of modest difficulty, this route is done by most teams in a day from an early start. Moving together on the easy ground should see most teams up the face in a decent time. The route is often very busy and so having an efficient way to overtake and get into your space is advantageous. One of the main difficulties lies in the descent. There are several options here:

The easiest is to descend down into Val Masino in Italy via the Rifugio Gianetti and take a taxi back. This requires a couple of hours of scrambling down and then an hour and a half walk to the valley.

Another option is to descend to the Rifugio Gianetti as above and then to return to Sasc Fura via one of the two cols either side of the peak – this is pretty alpine and will take the best part of 4-5 hours.

Descending the North Ridge is the most logical option, however, it is not easy. It requires lots of abseils and some exposed down-climbing to do it in a decent time, but it is well equipped with large rings to abseil from. We did this with a single 60m rope and a bit of scrambling off the ends and found it relatively efficient, but it still almost took as long as climbing the route!

Another option would be to descend the North Ridge and then abseil one of the bolted lines like 'Another Day in Paradise' if using two ropes.

Tre Cime (Cima Grande)

The Tre Cime (2999m) are one of the iconic symbols of the Dolomites, attracting thousands of visitors each year who come to walk around the towers and look at the steep faces. The largest of these towers is the Cima Grande and it was this face that Rébuffat immortalised in his list. It was first climbed by local Dolomites climbers Emilio Comici and the brothers Dimai, all pioneers in the area at the time, over three days in August 1933. It marked a big step up in rock climbing at the time as walls as steep and large as this were previously off limits and marked the start of the VI grade. It was largely possible at the time due to heavy use of pegs, but is now done as a free climb, however, it is hard not to marvel at their audacity to quest onto such an imposing face.

The route follows a steep line up weaknesses on the right hand side of the face but doesn't really relent until ledges are reached at two-thirds height. From here, the face leans back following chimneys to an exposed traverse and easier ground to the ring band that circles the upper part of the mountain and marks the end of the route.

Like the Piz Badile, conditions here are pretty reliable and just need dry, stable summer weather. However, unlike the Piz Badile, the atmosphere of the face is a lot more serious and the risk of rockfall is higher as well as the climbing grade is a fair step up and of a more athletic nature. With that said, the ease of approach, retreat and route finding and the smaller length and lower altitude make it more friendly and so probably a good next step.

Comici-Dimai (VII+) Route

Grade: TD+ 6b+ (E3)

Length: 600m

Start Point: The route is accessed from the Tre Cime parking lot (possible to camp here) by the Rifugio Auronzo and takes a mere 45 mins – hour walk to get to the base!

Conditions: This route is rock based and so just needs dry conditions meaning any dry period between late June and October should be possible. Being very steep and north facing, the route gets little sun meaning that after rain it may take a few days to dry – it's pretty common for the upper chimneys to be wet.

Topo: Paroi de Légende, Classic Dolomites Climbs, Rockfax Dolomites and Camp2Camp.

Gear: Summer rock climbing gear and approach shoes and more quickdraws than you would normally take (~15 or so) to clip the large amount of pitons.

Difficulties: The main difficulties are centred in the first half of the face with a polished 6b pitch relatively close to the start and a couple of harder pitches before the ledges at two thirds height. Most of the route is heavily pegged and many belays cannot be backed up so a healthy trust of pegs would be useful. Consequently a lot of the difficulties can be French freed if necessary. The rock takes some getting used to as it's not the most solid feeling and very steep – similar to Swanage…

Dangers: Loose rock and possible rockfall from above are the main objective hazards here.

Tactics: Being low altitude and not particularly long (in terms of this list), this route is done by most teams in a day. With it's popularity an early start is advisable to get on the route first and not held up in queues as it is hard to overtake in the first half of the face. In general, route finding is pretty simple. There are two possible exits with the classic one taking chimney systems that are often wet – if you think this might be the case then taking the slightly harder Constantini finish might be advisable unless you like gorge walking. The descent down the Normal route is well travelled but a good topo should be taken as it is not always obvious and would be easy to get lost – most is down climbable with a handful of abseils near the start.

Petit Dru

The Petit Dru (3733m) sits presiding over Chamonix, a large rocky bastion that has no easy way up it. It is one of the most iconic peaks in the Mont Blanc massif and the only face in this list to be climbed by a French team first. Pierre Allain and Raymond Leininger climbed the route over three days in 1935 — it had previously repelled several Swiss teams and Allain, climbing the crack of his namesake on the route, set a new level of difficulty in the Massif at the time. They would go on to make several first ascents across the French Alps such as on the Meije and Charmoz. Unfortunately, the peak has suffered several rockfalls since the turn of the century that have altered the character of the route, making the once heavily frequented classic a fair bit quieter — one of the few faces on this list that this can be said about!

The route follows a chimney system to start that gains a right trending groove system (interspersed with a squeeze chimney) that leads to the Lambert crack. Awkward climbing up chimneys above this lead to the Niche. A steep chimney system to the right of the niche is climbed and then the route becomes quite hard to follow, trending up the upper pillar via steep slabs and flakes until the quartz ledges are reached. From here chimneys lead up to easier ground and then it is possible to squeeze through a hole to the south face and ledge systems to the summit, or continue a couple of pitches up the north face to the same point.

This route was previously always done in summer, but in recent times (due to the dangers of rockfall) it is now much more commonly done in spring and is a much more significant undertaking in these conditions. It is quite a big jump in difficulty from the first two and requires significant route finding, a complex descent and several tricky pitches of 'old school' climbing in addition to a much higher objective risk. Personally, I think as a spring/winter route it would probably be considered harder than some of the other routes on this list, but I have put it here to reflect its traditional place in the list.

Allain-Leininger The North Face (TD+ 6a)

Grade: TD+ 6a/M4+ (E1/V)

Length: 850m

Start Point: The route is most often done by camping the night before on the moraine below the north face (in winter) or the cave bivvi on the same moraine (in summer). In winter this is accessed on skis from the Grand Montets ski area either via the Poubelle Couloir or the Couloir de Lapin. In summer, this is accessed from the Montenvers train and then either the Passage du Guide (below the Flammes de Pierre) or the Charpoua ladders.

Conditions: Traditionally this route was done in summer and needed dry conditions as it is rock-based and good glacier conditions for the descent across the Glacier de la Charpoua were required. More commonly these days, the route is done in spring in periods of high pressure due to the danger of rockfall on the Dru following the recent hot summers. This increases the difficulty of the route as more of it has to be mixed climbed and generally conditions are harder going with less light, but overall it makes it a much safer proposition (this is the advice of the PGHM and OHM). An ideal situation would be high pressure and generally dry on the face in spring.

Topo: Snow, Ice and Mixed Vol. 1 (2019)

Gear: Winter climbing gear and sleeping kit plus skis for approach. If going in summer, then standard alpine rack, axe, crampons and boots for the descent.

Difficulties: Whilst the difficulties described in most topos are given to the named pitches such as the Lambert/Martinelli/Allain Crack pitches, most people I know have found the pitch following the Lambert crack to be the hardest. This follows a chimney groove that is often verglassed to an extent that it is too thin to use for axes but too much for gear/feet etc. and most people have performed some sort of pendulum manoeuvre to overcome it using a flake. Outside of this, the Martinelli is easily used to avoid the Allain crack and a lower chimney pitch can be run out and tricky if there is little build up of snow in it. The route finding in the upper face is not obvious and this can also be a big difficulty and slow progress.

Dangers: Rockfall is a big risk on the mountain as well as potential loose rock. Ice fall if descending the North Couloir and crevasse danger on the Glacier de la Charpoua.

Tactics: Previously when done in summer, it was common for most teams to go up and over in a day from a bivvi on the moraine to the Charpoua hut. Nowadays in spring most teams will spend a night somewhere on the face (possibly more) before returning to town. The best bivvi spots are a pitch above the Niche that overlooks the West Face or near/on the summit after popping through the hole to the south side. Earlier in spring it is possible to abseil the North Couloir – this is advantageous as it gets you back to your skis and camp at the base. Later on in early summer it is best to continue to the top of the Grand Dru and follow the bolted abseil piste from there to the Charpoua (marked by cats' eyes). The drier the route is (without being too hot) and the more you can rock climb, the quicker and easier it will be.

Matterhorn

The Matterhorn (4478m) is the highest of the faces on this list and is the emblematic symbol of Zermatt and the Valais. It was the first of the routes on this list to be climbed, when it was climbed in the summer of 1931 by the brothers Schmid over three days. They kept their plans secret so as not to attract competition and cycled to the peak from Munich. Since then the face has retained a lot of its mystique with its being relatively fickle, meaning would-be climbers have to have their eye on the conditions year by year. It was also the site of Walter Bonatti's final big new route in his career when he forged a direct line up the face solo in winter, which still sees few repeats.

The route starts by following 500m or so of 60 degree névé or ice before cutting right into a long diagonal ramp system that leads across the face to the Zmutt shoulder. This ramp consists of moderate mixed climbing on pretty bad rock before cutting right to a 50m water ice pitch that leads to easier mixed ground and the ridge. This is followed to the summit.

The main difficulty of this route is finding appropriate conditions as in recent years, ice doesn't always form on the face and without it, the rock is pretty bad. This route is never particularly difficult but it is long and has significant altitude that needs to be overcome, but as most teams won't need a bivvi, it is the easiest of the big three (Matterhorn, Jorasses, Eiger) and personally, I feel potentially easier than the Dru.

Schmid Route Schmid Route (North Face) (ED1)

Grade: TD+ 4+ (V)

Length: 1100m

Start Point: The route is started from the Hörnli hut above Zermatt, which is accessed from the lift system and a couple of hours' walk. From the hut the base of the route is reached in about 40 mins or so by traversing across the glacier with a small pitch of mixed, normally with a fixed rope.

Conditions: This route is one of the harder ones to find in good conditions, being reliant on ice and if there is any, it is often swamped with people. The two main periods when there are likely to be good conditions are late spring after a good winter, when the face is plastered with névé (beware if it is just névé on top of rock though without ice, as the rock provides little protection due to its friable nature) or in autumn after a wet summer. There is a good webcam that can help assess what the face looks like on the Zermatt website.

Topo: Many available online and a good description on Camp2Camp.

Gear: Winter Climbing Gear plus a stove and some extra food (in case of a night in the Solvay).

Difficulties: The main difficulties are in the diagonal ramp section midway up the route, where there are a couple of pitches of mixed (M4ish/Scottish V) and a long 50m ice pitch (Scottish V-ish). It is also a long route with a complex descent and any team wanting to do it in a decent time should be prepared to simul-climb a lot of the first ramp and easier ground on the shoulder. The other main difficulty is the altitude—with this being the highest mountain on the list, it shouldn't be underestimated.

Dangers: Ice fall from other teams and rock fall from the face in addition to poor, friable rock quality on the mountain. The initial glacier crossing has some crevassed areas.

Tactics: Most experienced teams will either aim to get back to the Hornli hut in a long single push or will crash at the Solvay bivvi hut on the descent (one-third of the way down). This means that only day kit needs to be carried and a stove. Bivvyng on the face is likely to be pretty unpleasant as there are not many good ledges. Most of the route-finding is relatively obvious, except for the transition from the starting slopes to the diagonal ramp where you need to stay low and not be drawn into a mixed corner higher up.

Grandes Jorasses

The Grandes Jorasses (4208m) is the face here that has most interest for multiple visits, with its kilometre-wide north face criss-crossed with close to 50 routes. It is one of the most remote-feeling of the faces on this list, being situated at the far back of the Leschaux basin, not visible from a valley base, and requiring more complex logistics, starting in France and ending in Italy. The face had been attempted since the 1920s and had repelled most teams including some of the strongest alpinists of the day like Schmid and Gervasutti. A German team succeeded in 1935 to climb the Croz Spur (parallel to the Walker) but the Walker remained elusive. In August 1938, annoyed he had been pipped to the Eiger north face by Heckmair, Riccardo Cassin with Tizzoni and Esposito climbed the Walker Spur over three days, making it the last of the routes on this list to be climbed. Nowadays, it's one of the most popular 'hard' routes in the Alps.

The route follows the spur that falls down from Point Walker, the highest summit of the Jorasses. It zig-zags its way up passing the Rebuffat Corner early on – a 6a slabby corner. Not long after it passes the 90m dièdre – a large corner system with some lovely climbing. After this it heads rightwards with a pendulum followed by the Grey Slabs, the crux of the route featuring 6a climbing over three pitches. Easier climbing up the crest leads to the Red Chimneys (poor rock and possibly some mixed ground) before swinging right around a final rock bastion and following gullies and the crest to the summit.

It is a long route and in the past was considered as hard as the Eiger, if not harder. With the advancement in rock climbing ability and equipment, this difficulty has diminished a little bit in comparison with its mixed counterparts, however it remains a long, sustained route with a complex descent that is a good test for experienced summer alpinists.

Walker Spur (ED1 6a)

Grade: ED- 6a (E1)

Length: 1200m

Start Point: The route is started from the Leschaux hut, which is approached in 2-3 hours from the Montenvers train. From the hut it is a further two hours to the base of the route, navigating the Glacier de Leschaux.

Conditions: Being a summer route, finding conditions for it is considerably easier than the Eiger and Matterhorn. Generally, each year, in July to September there will be several weeks of good conditions where the spur is primarily dry and it is not too hot. One of the big factors in recent times has been rockfall and it is not always a good idea to climb this face in a heatwave (even if it is dry) as this is often the time of most risk. Once the first snows come at the end of August, the aspect of the face and lack of sun can spell the end of good conditions (but it can still be climbed with a bit more mixed). The Leschaux hut can be called for conditions information.

Topo: JME Grandes Jorasses book.

Gear: Summer climbing gear and kit for glacial travel, axe (possibly two depending on conditions), crampons, boots, sleeping kit.

Difficulties: The main difficulties are the pitches on the Grey Slabs and the Rebuffat Corner low down. The Red Chimneys high up can be tricky also but mainly due to the poor rock quality here and not wanting to knock anything off. The route is very long and relatively sustained with a fair amount of route finding, altitude and with a long, complex and objectively dangerous descent this all adds up—added to the likelihood of it being busy in peak season.

Dangers: Rockfall is a big one, with the face being more prone to this in recent summers as well as from other teams – particularly near sections such as the Red Chimneys that are less secure. The glaciers on approach and descent are heavily crevassed and need attention as does the large serac on the south side that is passed under on descent.

Tactics: The classic way most teams will do it is from the Leschaux hut and they will often bivvi somewhere high on the face (bivvi sites on the final ridge section after the Red Chimneys) or on the summit and descend the next day. Very fast teams may be able to make it to Val Ferret in a single push. Another approach would be to start from the first Montenvers train, walk in and start climbing, aiming to bivvi below the Grey Slabs (where there are several good bivvi sites) – if going for this option, beware of not having anywhere to sleep if the face is busy – there are only so many good ledges. One factor to consider is water as later in the season, finding snow to melt on the route can be an issue – so carrying more can be better in this situation. The descent down the South Face is non trivial and takes between 4-6 hours, so it is a big undertaking itself with risk from the large serac below Pointe Walker and significant crevasse hazards, so it should be taken with good energy levels.

Eiger

The Eiger (3970m) is by far the most famous north face in the world and well known amongst non-climbing circles due to books like Harrer's The White Spider and countless films and documentaries. Serious attempts started on the face by Austrian and German teams in 1935 and killed most who attempted it over the years following until it was climbed in July 1938 over several days by Anderl Heckmair along with Kasparek, Harrer and Vorg. By this point it had gained quite the reputation as a deadly face. To this day, it has kept its aura with its poor rock, fickle conditions, hard climbing and commitment providing a stark contrast to the benign surroundings of the ski area below and the train that runs through the heart of the mountain that makes access so easy.

The route is the longest on this list as it weaves about the austere face finding the areas of weakness. It starts up easy snow gullies before tackling the often dry 'Difficult Crack'. From here it moves left and joins fixed ropes on the 'Hinterstoisser Traverse' that gives access to the first snow field. From here the 'Ice Hose' leads to the second snow field that is traversed leftwards to a pitch of mixed and the 'Death Bivvi'. From here the ramp system is gained that heads up and left until it runs out, giving way to the 'Waterfall Chimney' and slabs above. Above this we reach the 'Brittle Ledges' and crack. Here the route works back right across the 'Traverse of the Gods' to the 'White Spider' snow fields and the 'Quarz Crack' above. Once past this the 'Exit Chimneys' and ice slopes lead to the ridge and summit.

Today, the route is still considered one of the most coveted routes in the Alps and with global warming has become more fickle and dangerous with the crowds that come with good conditions. Despite the advancement in mixed climbing ability and equipment, the face is still a big challenge due to its length and number of difficult pitches and unlike the other routes on this list (except potentially the Dru) requires bivvying on the face in winter conditions for one or more nights, taking the level of suffering up a notch, not to mention the time spent on the face. For these reasons I would consider it the hardest of the routes on the list (although I know others would disagree…).

The 1938 Route (ED2)

Grade: ED 5+ (VI)

Length: 1600m

Start Point: The route is started by a short traverse (~45 mins) from the Eigergletscher station that can be reached from a cable car from the Grindelwald Terminal.

Conditions: Like the Matterhorn, the Eiger north face is hard to find in good condition, where you want good ice and névé on the snow fields and key sections (ice hose, ramp, exit chimneys). This is likely to be in autumn or more commonly in recent years, spring, however, finding good conditions up the whole face is rare and climbing some parts in trickier than normal conditions is not uncommon. It is not in good condition every year and would-be climbers should have their eyes on conditions (and the Grindelwald webcams).

Gear: Winter climbing gear and sleeping kit.

Topo: Many available online and the Rockfax 1938 Route mini-guide is useful.

Difficulties: The Eiger often feels like a computer game with lots of easier ground interspersed with a boss harder pitch of climbing – especially as they are all named. The main tricky pitches are the Waterfall Chimney and following slabs which can be iced or dry rock and the Quartz Crack higher up (although this is well equipped). Otherwise the Difficult Crack, Ice Hose and unnamed bit of mixed leading to the Death Bivvi all felt a bit harder than the rest. In general, the route has a lot of fixed gear on the named sections and being able to move speedily and safely along the long unprotected snow fields is important as well as the ability to deal with loose rock. The fact that this is two days out in a winter environment with a bivvi makes it a big undertaking.

Dangers: Rock and ice fall is common on the face and the rock is generally of poor quality, so is prone to being loose. The cold is a big problem here and teams will need to be able to cope with this for a sustained period on the face. A serac is passed under on the West Flank descent.

Tactics: Most teams will do this in two days from the first lift (or a bivvi at the Eigergletcher) with a bivvi at one of the known bivvi sites (Death Bivvi, Brittle Ledges) and some will possibly make a further one on the summit. Very fast teams can do this in a day but it is not super common and will be done from a bivvi at the Eigergletscher station. The descent is relatively quick down the West Flank, but has the objective hazard of passing under the serac, which should be passed speedily.

For fans of this genre of climbing, some other big classic (but more obscure) North Faces around the Alps would be:

Mont Blanc Massif: Droites (Ginat/Tournier Direct), Grand Pilier d'Angle (Cecchinel-Nominee), Sans Nom (Brown-Patey), Grand Charmoz (Merkl-Welzenbach)

Ecrins: Ailefroide (Devies-Gervasutti), Meije (N Face Direct), Olan (Couzy-Desmaison)

Valais: Dent Blanche (N Face Direct)

Oberland: Finsteraarhorn (North Rib), Monch (Lauper), Lotschetal Breithorn (N Face), many more…

Bregaglia: Cengalo (Gaiser-Lehmann)

Dolomites: Civetta (Philip-Flamm/Solleder/Aste), Monte Agner…

However, most people have probably had their fill after these six and probably want to stay on the classic South faces…

Guidebooks

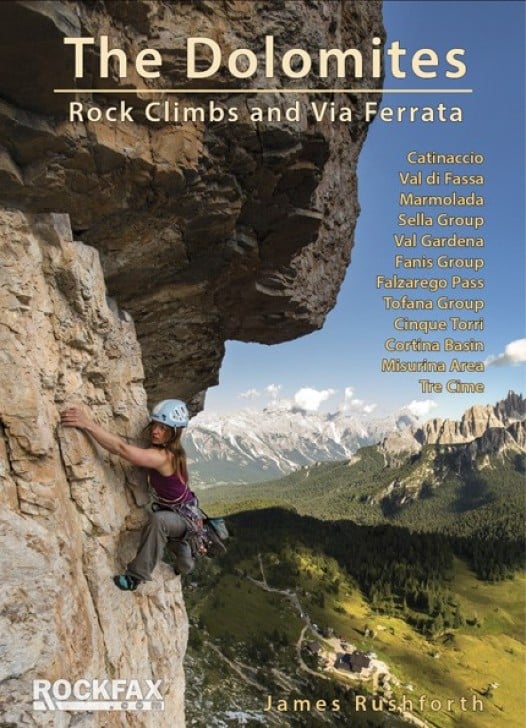

The Dolomites : Rock Climbs and Via Ferrata

A big book to the magnificent Dolomites in northern Italy. This guide covers everything you need for a climbing trip regardless of ability, whether it be sport, trad, via ferrata or a combination of all three. It features all the major areas and is the only guidebook available to have such comprehensive coverage.

The 2019 edition has around 40 updated descriptions and small changes but covers the same crags overall.

Comments

Good Article Luke!

Walker and Matterhorn left for me!

You're a god, Tom !!

Good article. I had always fancied the Walker, but all that talk of rock fall has put me off!

An excellent article, thanks!

Hey Jon,

Hope you and H are well.

I presume that is reference to my name change?

I changed it on Instagram shortly after I qualified, and for some reason Meta also changed it on Facebook too.

Since then I get quite a lot of private messages asking for guiding, so I thought it was worth doing on UKC (which is sort of social media) too.

Cheers,

Tom

p.s: The BMG is 50 in 2025. We’re going to do some sort of celebration. Would you like to come?