Dave Pickford explores the value of climbing through three lines of enquiry: the value of climbing to those who choose to climb, the value it has, if any, to the rest of humanity and the value it could bring to people in the future.

Somewhere high above, hexagons of sunlight refract and merge. I glance upwards. A thin vein of white cloud streaks the sky above the Russian Tower. I breathe in deeply and exhale. The air is cold up here.

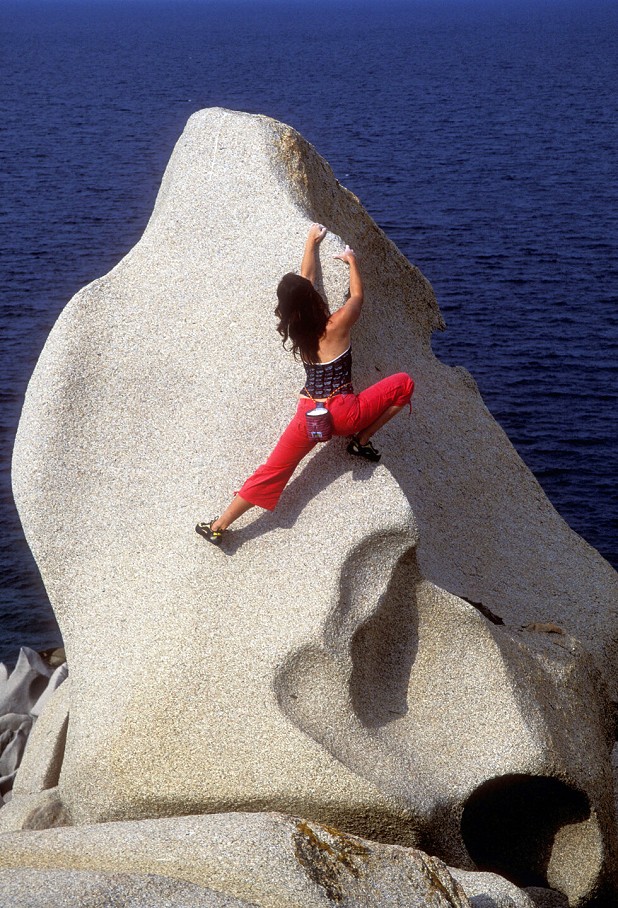

What's happening? As my feet begin cramping, my left boot slips slightly on the smear, and an electric current jolts my limbs back into movement. I've been standing here, near the top of this unclimbed, two-hundred-foot sweep of ash-coloured granite for twenty seconds at least. Too long, probably.

Below, the slab barrels downwards into darkness and distance. I cannot see the last gear in the break forty feet above the deck. The gear doesn't matter, anyway; I'm a hundred and twenty feet up and very much alone. If I fall, I'm going all the way. Crash-landing down there, among the glacial boulders of the Ak Su valley in southwest Kyrgyzstan—two days' walk from the nearest inhabited place—would be an extremely bad idea.

What are you doing here? asks a quiet voice in my head. It's a refrain that's returned again and again through all my years of climbing, like the disembodied wisdom of a protective godfather. After another five seconds of pondering, I realise that I'm far too high up this thing to even contemplate reversing the sustained, delicate climbing I've done to get here. The only option is to make the moves.

White light blurs the edges of my vision, and I commit.

Thirty seconds later, I'm pulling over to a ledge of sweet-scented alpine grass and the sanctuary of a huge belay boulder. After a while, my heartbeat slows. Listening to the churn of the glacial river far below, I began to take in all of what had just happened on the climb, as I had so many times before and as I would again.

***

Along with its sometimes life-preserving attributes, the query 'what are you doing here?' contains specific, important questions about the essence of climbing. What value—if any—does climbing have? Why do we put ourselves in scary or downright dangerous situations on the rocks and in the mountains? What, really, is the point of it all?

In his book Alone On The Wall, published in 2015, the American climber Alex Honnold—unquestionably one of the boldest actors in the sport's history—argues that '[Along] with the critique that climbing is selfish is the claim that climbing is useless. But I think that perfecting your skills on rock (or ice and snow) ends up improving you in other ways. I fully believe what I've learned from climbing translates into other aspects of life.'

I wanted to explore Honnold's point in greater depth: to ask what we might gain from climbing rather than why we do it, and to ask how the things we gain from it might change our lives in ways we don't necessarily fully understand.

Motivation versus Value

Over the years, plenty of perspectives have been offered on the reasons why people go climbing. Of these, George Mallory's quip that he wanted to climb Everest "because it's there" remains not only the most overused but also probably the least substantial of the various explanations for why we climb. We might climb a mountain because it's there, but we might use a spoon to eat our cereal because there happens to be a spoon somewhere in the kitchen, and we go to the pub to meet our friends because, well, there's a pub there. Just because something is there doesn't make it interesting.

Of course, a whole host of other, more sophisticated explanations for why we climb have also been set forth. One of the more interesting and psychologically charged propositions was once suggested to me by David Thomas, one of Britain's foremost solo climbers in the 1990s. He raised the idea in conversation that we might become interested in climbing as youngsters "because [our] parents don't show us the world". For some, I think, this provocative and intriguing suggestion might be true. Climbing may be an appealing and also a powerful tool for adventurous or rebellious adolescents to assert their genetic independence from their parents.

For others, though, the opposite could be the case. It has become fairly clear to me, after many years of reading around this jellyfish-like subject, that the only reliable link between the explanations for why we go climbing is the fact they are all quite different, and in many cases contradictory. The British climber, physicist and writer Phil Bartlett captures this situation in his excellent, far-reaching book The Undiscovered Country: 'One of the reasons for thinking mountaineering a noble pursuit is that it defies our attempts to categorise it and explain it away.'

In the spirit of this perspective, and in contrast to the conflicting assertions about individual motivation, the more substantial questions that surround the value of climbing—and their answers— might be found through three key lines of enquiry.

First, what's the value of climbing to those who choose to climb? Second, what value does climbing have, if any, to the rest of humanity; to the vast majority of people who will never climb? And third, what value could climbing have to people in the future and the societies they live in?

An Examined Life

About twenty years ago, a friend of mine told me something I'll never forget. He was, incidentally, well known in his youth for his audacious leads of adventurous British trad routes. We were working on a rope access job together when he threw this startling line at me: "You know what… I think climbing saved my life, really".

He'd grown up in a broken home in an area of a major British city known for its problems of social exclusion, drugs and crime; a close relative was serving an extended prison term for attempted murder. Given these facts, when he quit school in his mid-teens the possibility that he'd fall into a life of crime and become socially excluded was statistically quite high.

But then he discovered climbing, which changed everything. It gave him, he told me, "focus, drive, motivation; a sense of purpose in my life, a sense of community with the guys I was climbing with". Today, he doesn't climb as much as he once did. He now runs a successful life-coaching business. His powerful story shows, I think, how climbing can be a flare in the dark, a kind of guiding beacon that might radiate light into the shadows of existence.

Focus. Drive. Purpose. Community. The association of these qualities with climbing will not be surprising to anyone who climbs regularly. Yet it is not an exaggeration to say that most climbers—myself included—take the covert benefits of climbing entirely for granted. Yet the fact we don't necessarily consciously appreciate them every time we climb does not detract from their importance.

Plato's Apology, one of the great philosophical texts of the ancient world, remembers the speech Socrates gave at his trial, in which he chose suicide by drinking hemlock rather than exile from Athens or a commitment to silence. A few moments before his death, Socrates purportedly said "An unexamined life is not worth living".

An activity such as climbing, like anything else that requires the use of skill in a potentially dangerous environment, demands that its practitioners lead an examined life in various ways. It demands that we are physically fit and strong, well organised, and self-critical. It forces us make both considered, rational plans as well as fast, spontaneous decisions, exercising both the so-called System 1 and System 2 aspects of cognitive thought that the Nobel Prize winning psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman identified in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Perhaps most importantly of all, it requires that we develop high levels of environmental intelligence, which I would define as the quality of being able to operate efficiently in a hostile environment while leaving no trace of your presence. This is, of course, an incredibly useful, sometimes life-preserving skill, as any member of a Special Forces unit might tell you in more detail.

On a more existential level, leading what Socrates called "an examined life" surely also means that we examine what it is that we truly value, and therefore what we want to do in life, and to develop a belief system based around those values. For many climbers, such a belief system often involves a love of the outdoors and of the natural world, and doing something challenging with friends. For others, more interested in physical training, it might involve working towards certain level of athletic excellence over an extended period.

Yet whatever you believe is most important about climbing, the very fact you are going climbing at all means that you're realising your own version of Socrates' great dictum: you're living "an examined life" by doing something you believe in, and which might be quite difficult, and which has value to you and those around you. The late writer and journalist A.A. Gill brilliantly suggested that the art of successful living was about choosing what not to participate in. This is of course easier to appreciate as you get older, but if climbers often choose to prioritise their love of rocks and mountains over social events and shopping trips, it's perhaps because they're unconsciously following Gill's idea.

Sometimes, too, we can only appreciate the true value of any relationship by its absence. Hazel Findlay, the first British woman to climb E9 and to free Yosemite's El Capitan, once explained in an article in Climb magazine (issue 130) how she felt on touching rock again after a six month lay-off in 2015 following shoulder surgery:

"[The first route I climbed after the operation] was ridiculously easy. But it was blissful; I want climbing. Even with my weak body, my whole being drank up those moves like a parched woman licking water droplets off a windowpane." This startling metaphor of the vertical world as a form of vital hydration captures much about the value of climbing to those doing it regularly.

Climbing can be an athletic discipline, an exploratory quest, a meditation ritual and a series of social interactions. Its highly addictive nature for younger people in particular might be explained by the fact that it can be all these things at once. It fulfils the need for the hunt and also for the dance that are central to many tribal cultures. As such, it is a triumph of the scope of the human ingenuity for repurposing ancient rituals into modern mediums.

At a push, the pursuit of climbing as a formal discipline is no more than a couple of hundred years old. Despite the relatively low participation numbers compared to mainstream sports such as running, it boasts a body of literature and film that can rival that of any other sport, much of which is read and watched by people who are not participants but armchair enthusiasts. This is another measure, I think, of its unique value.

Inspiration and Myth

To the second of the three areas of enquiry: what is the value of climbing to the world at large? At first glance, this seems a difficult question to answer; but the response is relatively straightforward.

At the most fundamental level, I believe an activity like climbing has value to those who do not climb because human societies still demand myths, in the same way that past societies once did.

The twentieth century American mythologist and academic Joseph Campbell once said that "myths are public dreams, (but] dreams are private myths". Since climbing creates a vast corpus of powerful stories, some of these stories enter the cultural imagination of their time, where they can quickly become myths. Campbell's most famous concept is that of what he called the 'monomyth'. It's best known for being hugely influential on Star Wars creator, George Lucas. The idea essentially regards all mythic, heroic narratives as adaptations of a single great story that lives at the heart of human consciousness. In this single story, Campbell suggested that a common pattern exists, regardless of the origin or time of creation of any individual narratives.

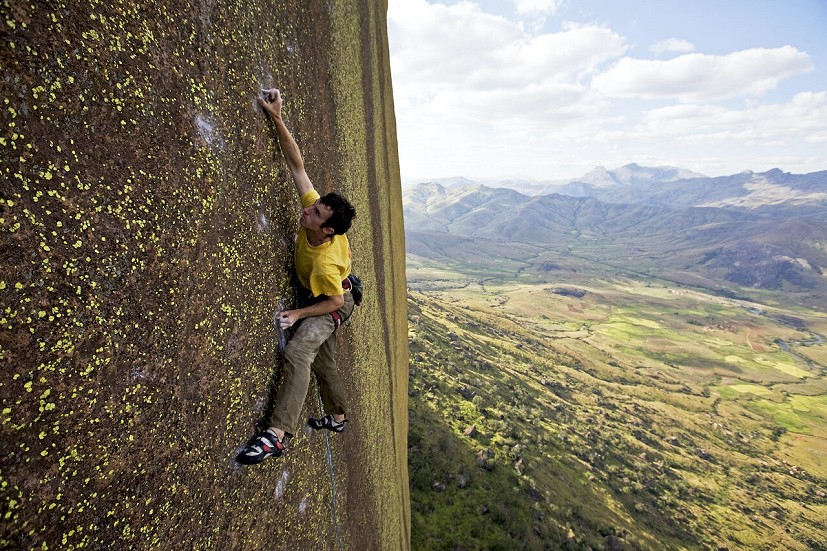

Central to the monomyth concept is Campbell's notion of 'The Hero's Journey' (detailed in his book The Hero With A Thousand Faces), in which a heroic figure goes on a quest, experiences various trials and suffering, and returns with gifts or wisdom to set their people free. Most of the greatest and best-known climbing stories are striking examples of Campbell's hero's journey. It might be a reflection of the importance of Campbell's idea that those rare climbing stories that actually reach the mainstream media are often received by the public with enthusiasm, such as Joe Simpson's mountaineering survival epic Touching the Void, or the film Free Solo, documenting Alex Honnold's extraordinary ropeless ascent of El Capitan.

Another prime example of climbing myth-creation in recent years is the first free ascent of the Dawn Wall in Yosemite in January 2015. The real-time reportage of the climb on social media by Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson captured the public imagination in an extraordinary way, partly because it felt as though we were watching a myth being made.

Most who followed didn't know anything about big wall free climbing; not least the President of the United States, Barack Obama, who tweeted enthusiastically about the ascent. While Obama was unable to appreciate the climb's technical difficulty, he certainly could appreciate the mono-mythical power of the story: an epic quest to scale a piece of sheer granite half a mile high.

In a lecture at Kendal Mountain Festival in 2015, Tommy Caldwell explained how following their ascent, he was approached by an elderly woman in a wheelchair who suffered from multiple sclerosis. She told him that his climb had given her the inspiration to get out of her wheelchair and walk again. I thought it was one of the more powerful illustrations I'd ever heard of the possible value of climbing as myth and inspiration to the world at large.

The precise construction of Joseph Campbell's 'Hero's Journey' doesn't apply to all climbing stories. In many of the most famous mountaineering stories, the hero dies before the end, and George Mallory's final attempt on Everest in 1924 is perhaps the ultimate example of this. Yet it is one of climbing's most powerful myths, largely because we still do not know, and probably never will, what the outcome of the story was.

However, even if the climbing hero, like Mallory, does not survive, such stories are nonetheless important; and possibly more so today than ever, because we are increasingly isolated from the reality of death. We need myths of people dying in pursuit of a noble cause—such as in Christianity's Crucifixion story— or a personal calling because they remind us that our mortality cannot be taken for granted. So the hero does not have to survive and return with gifts to set their people free. The story itself, like Mallory and Irvine's tale and so many other epic but ultimately tragic climbing narratives after it, could be enough.

How, though, can we summarise the value of climbing stories to non-climbers? After a motivational talk I gave at a school a few years ago, in which I spoke about how dealing with risk, and even the possibility of death, in adventure sports can give us confidence to make difficult decisions elsewhere, a teenage girl quizzed me on my photos from the mountains of Madagascar. She said my talk had confirmed her desire to travel to Africa after her A-levels. She wanted to climb Mount Kenya after volunteering in Malawi. I realised that climbing adventures don't just have value to those who engage in them; because they have the power and simplicity of more traditional myths, the stories that climbing generates have a surprising value to many other people, too, in many different ways.

Beyond the Shadows

And so on to the final enquiry: what value will climbing have as it evolves in our future society? In the Golden Age of alpinism in the nineteenth century, Victorian gentlemen of leisure sought untrodden summits in the Alps—a natural extension of the ambitions of imperial nations. A hundred years later, in 1980s Britain, groups of young climbers would live together in shambolic shared houses in Sheffield and Leeds, their lifestyle of full-time climbing supported by the generous unemployment benefit of Thatcher's government.

This shift away from climbing as a pursuit mainly of the aristocracy, as it had been in the era of the Golden Age of alpinism, also marked the beginnings of the modern era of professional climbing and training. Today, at outdoor trade fairs, young sport climbers and alpinists converge, circling the stalls like hungry hawks, hoping to catch an influential marketing manager's eye with a presentation on a travel-scuffed laptop documenting their achievements. Climbing has now truly gone global, like much else in the modern era. But what can we learn from these disparate paradigms?

Throughout its relatively short history, a single feature of the way in which climbing and mountaineering have evolved has been consistent: all climbing cultures have reflected and channelled the moral and cultural values of their time. Climbing is as much a mirror of the society in which it takes place as it is a transgression of it. All the talk of counter-culture in the British and American climbing scenes of the 1970s was a classic example of climbing following rather than rebelling against the Zeitgeist; the Yosemite dirtbag era was like a microcosm of the Woodstock Festival with ropes—and possibly even greater quantities of marijuana.

It is likely that climbing will evolve in fascinating ways over the coming century. The extraordinary things that are happening in climbing today, from speed-solos of 8000 metre peaks to 9c sport climbs and boulder problems of extreme difficulty, are to some extent a product of the ongoing development of what technology journalist Kevin Kelly has called the 'technium', describing how technologies don't develop in isolation, but rather evolve together, and create self-improving tendencies in a similar manner to the process of natural evolution. The advancement of climbing and mountaineering cannot be separated from the parallel development of the technology and equipment used to facilitate it.

For example, new paraglider technology is already changing mountaineering by providing pilot-alpinists with lightweight canopies to fly base-to-base for Himalayan objectives in a few days— feats which would previously have taken weeks. Fine-tuned climbing skills and new technology can interact to create possibilities undreamt of in previous generations.

With a long way still to go, one overwhelming question remains: in what ways will climbing be valued by future generations? Will they love the cliffs and mountains in the same way that we do? And what exactly will they do out there?

Part of the answer to this question is obvious. A lot more people will be climbing in future than there are now. In 2010, the United Nations forecast world population with three possible outcomes by 2100: two of these outcomes suggest that by the end of this century the world population will have reached circa ten billion or sixteen billion respectively; a huge increase from the 7.4 billion people alive today.

Some people in the outdoor community consider the sheer scale of this predicted human demographic expansion a potentially grave threat not just to wild spaces but to the general ethos of the outdoors. Part of the point of wilderness is the absence of other people in it. This problem can already be seen on busy weekends in many of Britain's national parks.

At the same time, in a world with ever more people (the majority of whom will live in urban or suburban areas) the public sense of the value of the outdoors—and of adventure sports—may increase rather than decrease. Since a mountain environment is so very different from an urban environment, more people may become interested in mountain sports simply because mountains themselves seem increasingly exotic to the city-dwellers of the late twenty-first Century. Whatever the future relationship between climbing and popular culture, the need to protect climbing areas will remain strong.

However, the current signs for this trend are encouraging: today, globally, there are circa 1840 National Parks; a vastly greater number than there were even thirty years ago. And the IUCN, (the International Union for Conservation of Nature) now represents more than 100,000 protected areas worldwide. The chances that the regions where climbing happens will be preserved for future generations to enjoy looks much more likely today than it did in, say, 1980.

Some British climbers talk about the scope for new routes 'running out'. While this is true on the more popular British cliffs (which are among the most intensively developed climbing areas anywhere on Earth) there are still places even in the UK where excellent climbs have yet to be discovered, such as on the high crags of the Scottish Highlands and Islands, and on many of the more inaccessible sea cliffs in England and Wales.

Globally, the scope for the development of climbing areas is incalculably vast. Even though a lot of the world's highest mountains have been climbed, a vast number of 6000 metre peaks remain unvisited, some of which will provide outstanding alpine climbs in remote places. The development of new climbing areas in emerging economies will continue.

Climbing in Britain, which was once a truly niche activity guarded by a coterie of self-appointed patriarchs in arcane clubs, has become a far more inclusive activity than it was. This hugely positive development signals the way the value of climbing will grow in the future simply because more people from different ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds will have access to climbing.

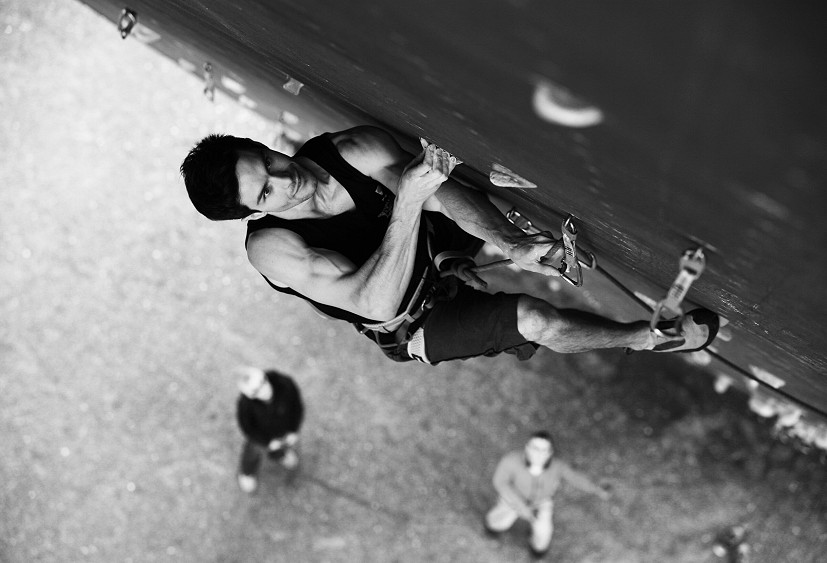

Almost as many women as men now climb in Europe and North America. The explosion of indoor climbing in cities means that more young people from disadvantaged backgrounds will be exposed to it, creating the chance that climbing will transform their lives. This process will have other implications about the way climbing is projected by the mainstream media and perceived by the wider public: could professional competition climbing compete in future with top-level international tennis for TV audiences?

Some newcomers who choose a life in the vertical world will probably grow the value of climbing much as their precursors once did in another era, on a mountain far away and long ago. If this is projection is even partially true, then it shows that climbing and mountaineering do have an enduring value to human beings, something that's endures the shifting culture of a single generation or indeed an entire era.

One of the key pioneers of the Golden Age of alpinism, Edward Whymper, highlighted this value brilliantly: "There have been joys too great to be described in words, and there have been griefs upon which I have not dared to dwell." Whymper was right. Climbing can be fantastic, and it can also be awful. Quite a few of my friends have died climbing. And despite or even because of this fact, somehow I know no better explanation than Whymper's for the timeless power of life in the vertical.

Infinity's Players

The Covid pandemic that dramatically changed the world in 2020 and 2021 was an opportunity to reflect on many things. Central to these cogitations for me personally was a subtle but distinct shift in my attitude to travel. I've climbed in more than sixty countries worldwide, and feel very lucky to have done so. But since free-moving international travel was effectively put on hold from March 2020 to late 2021, I began to question my previous need to travel as extensively and as frequently as I could just to get my climbing fix—or simply for the sake of travelling itself.

Anyone who values climbing can't ignore the fact that a lifestyle of almost constant international travel is not sustainable from an environmental perspective, as climate change makes headlines and the Alps crumble. Doing fewer individual trips over the whole year, and perhaps longer ones in the same area, might be a better strategy. And an even better one than that might be to really dig into the untapped possibilities in your own backyard. In a country like the UK, with such a diverse tapestry of climbing, those possibilities are everywhere.

Towards the end of the final Covid lockdown in England in February 2021, I began revisiting a twenty-five metre boulder traverse underneath a Victorian viaduct ten minutes' drive from home. I used to climb it for training, but hadn't been there for fifteen years. The traverse was exactly the same, like an old friend; with precise, fingery, sometimes powerful moves and delicate footholds. My focused concentration was just as it had been before, in a different phase of my life. I could hear the tide sluicing in, the lonely rumble of a departing train, and the murmur of the wind cutting through the the winter air. There was a feeling of being completely alive in this strange, liminal place.

After a while, I pulled on again, heading into the shadows, my mind dancing in the light. Despite having climbed all over the world, underneath this railway bridge next to a major road that follows the riverbank near my home, I remembered that climbing is always beautiful, wherever and however you climb.

***

Much of what this essay has explored remains open to interpretation, so I'd like to offer a coda to that initial question of 'What are you doing here?' asked a few thousand words ago, standing on that lonely slab of granite in remote Kyrgyzstan. The American academic and intellectual James P. Carse observed that there two kinds of games in the universe: finite games and infinite games. Finite games end in a win for one party. An infinite game, by contrast, is played to continue the game. It doesn't terminate because there is no winner.

An activity such as climbing—diverse, self-organised, difficult, sometimes dangerous—defies attempts to categorise and explain it precisely because it belongs to the universe of infinite games. Along with the greater advances of human progress—things like science, poetry, medicine, art, and mathematics—climbing is a noble pursuit partly because it defies our attempts to define exactly and precisely what it is. Our desire to climb and also the true value we gain from it cannot, perhaps, be explained at all. And that could be the very thing that makes it so powerful.

Climbing is a macro-game without a clear beginning or an obvious end. While climbs themselves begin and end, our desire to do them doesn't start or finish; it is within us. The desire to climb—like the desire to explore the world, the oceans, or outer space—is part of human nature. And it will be part of our nature long into the future, this creative ambition etched on stone, then distilled into fire. Climbing, in this respect, is a direct expression of intelligence, desire, courage, and fellowship. These are good things to value in the world today, and in the unknown global landscape to come.

- ARTICLE: The Heart of Nature - Climbing as a Paradigm of the Human Condition 7 Nov, 2023

- ARTICLE: The Liminal Game - Deep Water Soloing Explorations on the Edge of Land 21 Mar, 2023

- Hampi Bouldering - A Photo Essay 20 Jan, 2009

- REVIEW: Posing Productions On Sight 14 Oct, 2008

- Tendon Master 9.2mm Rope 29 Sep, 2008

- Who's There? 15 Jul, 2008

Comments

Excellent

Joe Simpson not Tasker

I like the notion of finite / infinite games; hadn't come across that before.

beautifully written!

it brought to mind something from the book i’m currently reading – turning point 1997–2008, by hayao miyazaki (japanese animator/director of studio ghibli fame). in some of the essays from around the time of the release of princess mononoke (a fantasy animation film with a complex focus on how humans relate to nature), he brought forward the idea that in our relation to nature, we need to find ‘the function of the useless’.

that is to say, not everything – in his case, every stretch of landscape – needs to be understood in terms of which function it fulfills, what its use is, what category to sort it under, to appreciate its value. rather, we need to come round to appreciating some parts of nature for their lack of providing such a function. this grove just *is*, and that is its value.

maybe having such a ‘useless’ activity in our lives that we just do for what it is, not for deriving a gain from it or fitting it into a categorised system of things people have in their lives, is in itself, useful.

I believe that the concept of "Finite and Infinite Games" was first coined by James P. Carse in his book of the same name - well worth a read!