Robert has scaled 85 giant buildings, including many of the world's tallest structures. His usual climing style is solo, with just boots and a chalk bag. Most of his ascents have been straight forward and successful, but in 1999 Robert had to be rescued by abseil from the Grande Arche de la Défense in Paris, as he thought it too dangerous to continue his ascent.

Before his addiction to buildings, Alain Robert was a very gifted rock climber, and has climbed at a high level, including a solo of the technical and tenuous L'ange en decomposition (F7a) in the Verdon Gorge.

It wasn't all plain sailing in the rock climbing front either - in 1982 he suffered an awful accident whilst roped climbing, which left him in a coma for 5 days.

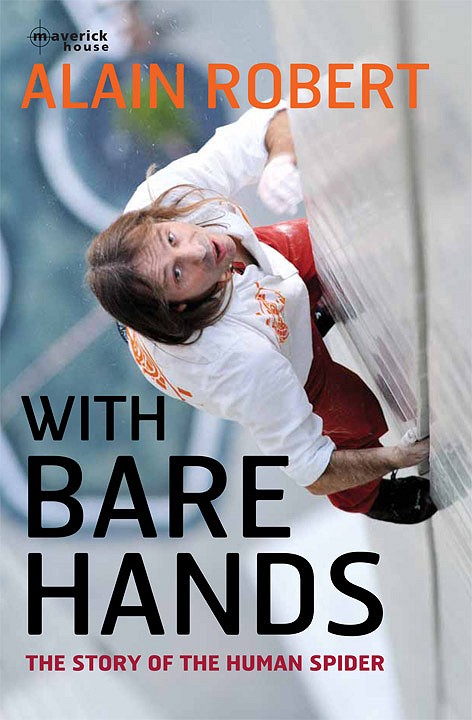

In the following extract from his new book With Bare Hands, Alain describes the turning point in his life, when a sponsor suggested travelling to Chigago and soloing a skyscraper.

Alain's publishers Maverick House have offered a whopping 40% discount on his book to UKC users. To order at this discounted rate - click here: www.maverickhouse.com

It's June 1994 and the telephone bursts into life at my little home in my native southern France. It's a rather intriguing – and, as it turns out, fateful – phone call. A film director is on the line. The famed sporting watches brand and one of the biggest sponsors in adventure sports, Sector, wants to sponsor a documentary about climbing entitled No Limits.

The guy on the end of the line tells me he has seen what I can do on the rocks and would like me to feature in his documentary. In an Italian accent he outlines his vision and says he is keen to show something different from the usual mountaineering stuff we are all used to seeing; he wants to break the mould and take the audience into pastures new.

The initial image he conjures up is the copper sandstone beauty of Utah, rugged landscapes belonging in popular fiction to the realms of the Marlboro cowboys, but in reality, of course, belonging to those who live on that arid land, the Navajo Indians. The second image he describes are the big city glass mountains, locations which teem with humanity to such an extent that we have utterly reshaped the environment, creating our own termite mounds of glass and steel. The director explains he wants to surprise the audience by drawing a parallel between the famous stony pillars of Utah and the gigantic office blocks of New York or some other city. In this documentary, he says, it will be necessary for me to clamber up these dreamlike sandstone obelisks and also to attack a high rise office block. He asks if I would be interested.

My curiosity is aroused and it seems to be quite a neat idea. It sounds pretty cool. Why not?

The director butters me up. He boldly declares he has all the angles covered and I need not worry about anything at all. We shall have shooting licenses and we will use a nice sturdy rope. Safety, he tells me, is naturally his highest concern. Location managers are devising a plan to obtain the rights to climb city skyscrapers as we speak. His crew is canvassing administrations and private owners to gain legal access to dramatic urban settings. If this falls through, the director will use special effects and models to recreate the city surroundings. The task for us is to come back with mesmerising, provocative and juxtaposing images forming a nice climbing story “made in America”.

I ask a few questions and he gives encouraging answers, and it all sounds positive, verbally anyway. So I tell him I am in. He makes a final round of assurances and tells me his staff will immediately make travel arrangements for me. As briefly as it began, the call ends.

Fissure escalation – the ascent of igneous, metamorphic or sedimentary rocks – has been my job for more than ten years. It's no problem; I've mastered it. I have tackled some of Europe's toughest climbs and have become known for pushing the envelope further by dispensing with safety equipment and climbing with my bare hands. Climbing in Utah sounds like a nice day at the office for me. But it has to be said that scaling the window panes of a tall building is something else entirely. What kind of idea is that? But never mind, I decide, let's give it a try.

Actually I have never even thought of the possibility of climbing manmade monuments. It has barely ever been done and I now wonder how I am going to do it. One of France's top rock climbers, Jibé Tribout, had scaled a building for an advertisement shot in Houston, so I decide to call him to get his point of view and gain his impressions on the feasibility of the project.

Jibé picks up the phone and listens thoughtfully before relating his experiences of such a climb. According to him, the ascent of a skyscraper is more hypothetical than realistic considering the height and the nature of the surface we have to work with. Besides, he hardly climbed a floor before jumping onto a crash mat like a stuntman. Even though he climbed a very different building, his experience had not left him a very positive impression of building escalations.

I thank him for his input and mull it over for a while. No one really knows anything about such a climb – it is a step into the unknown and will remain so until I attempt it. But within a few days I am flying to Chicago and any misgivings are packed in with my luggage.

On arrival I disembark to the news that we have only ten days to scout locations. I would have liked to have gotten over my jet lag, but to make good use of the day I head downtown to get a more precise idea of what we are looking at.

Once I get to downtown Chicago and walk the streets I am shocked. The profile of the buildings is quite a contrast to the modest heights of French cities. French cities have been around a lot longer and therefore tended to spread outwards over the centuries, rather than rocketing upwards as they have in countries where economies have exploded. Sure, there are tall buildings in France, but we have nothing like this. Here high rise blocks spring from the street, shooting up so far that they give the impression of overhanging the asphalt; they're incredible.

I walk the sidewalks with my chin pointing skywards, almost overwhelmed by the scale of it all. I remember having felt the same shudder, the same sensation of immoderate, gigantic size, the first time I discovered the Verdon Canyon in southern France. The famed gorge is the second largest in the world, and one of the most spectacular on the planet. Looking up at these glass cliffs I feel that same sense of awe. It is a long process, this adjustment, this experience of being tamed by a new universe and redefining your objectivity. The prospect of scaling these walls chills me. Even with ropes it looks immensely difficult or even impossible, and of course there remains the substantial risk. What was I thinking?

Right now I cannot imagine that I seriously intended to get my hands on a license and rope my way up this building armed only with the blessing of a priest. It would make more sense to cycle up Mount Everest. In the shadow of Chicago's cityscape, it occurs to me that I have probably agreed to one of the most stupid proposals that has ever been made.

But it is necessary to believe in oneself, to believe in the impossible, and not to give in to appearances. Naturally that's very easy to say. It's easy to laugh off a challenge, to dismiss it as a boyish prank, but when one is confronted directly by the challenge, suddenly there is nowhere to hide. Looking up at these monoliths I really start wondering what I have got myself into.

Then the Italian director really brings me down by giving me details about the hard tarmac below. The security services of these buildings are akin to George Orwell's Big Brother, with alert eyes and ears embedded in the concrete. Watching ... eavesdropping ... spying ... They will be on the lookout for troublemakers like me.

The director reminds me that the type of people found in the security industry are by nature physically aggressive, and some of them are drawn to an occupation that gives them the perfect excuse to assault people, especially here in “kick ass” loving America. I dart a worried glance at him, surprised to hear there could be a problem – I thought he had it all covered.

Cautiously we scout the city, visiting numerous sites each day, some higher than others. But there's no chance for me to set foot on any of them yet, as I am still waiting for official permission from any of the building managers the team has canvassed. A select few of these high rise buildings seem effectively “climbable”, on the premise of being able to use the rope every now and then to grab a little bit of respite to regain my energy. It's all looking and sounding very different to what I heard on the phone in France. And now here we are, at the launch pad, and the director drops a bombshell. He suggests it would be preferable if I were to climb a building without ropes. I wonder if he is joking or not. It doesn't look like it.

Another day passes and the whole project is still on hold, pushing up costs and mounting the pressure on the director. Then, for unexpected technical reasons, the shooting date is rescheduled to mid July. Apparently there is nothing I can do here any more, for now at least. So I head back to France, and an extra month of indecision passes by. In Valence, I try to climb some buildings to find the beginning of an answer, but it is impossible to compare a modest three-storey house with a fifty-eight floor skyscraper. It's rather like climbing a big pebble before facing the vast cliffs of Verdon. But anyway, I need to start somewhere, so I start climbing houses. As I climb a few of my friends' houses I notice that the French stone is cut, worked, sculpted, with any sheer verticality broken by ledges and mouldings. Such surfaces have absolutely nothing in common with 250 smooth metres of a North American glass wall. My bewildered friends watch on from their back gardens as I keep trying. I find a tennis ball but I get no closer to a solution to my dilemma.

A little before mid July, the documentary people call me with glum news. It will be impossible to obtain licenses ... but the company has already spent a lot of money on the production and locations ... and it's too late to stop the project. The company informs me that they will be shooting a base jump soon in the USA, and we shall therefore take advantage of the timing to shoot images of my rock escalation in Utah. But as for my proposed city climb, nothing is confirmed. If this mess of wretched permit papers arrives along the way, so much the better. If not, we shall just have to see what happens, Insha'Allah.

This disarray is what I face on my return to the New World, the wide open country of dreams and dreamlike landscapes. I am set to leave France with mixed emotions, possessing both a light heart and a heavy spirit. For me, climbing a pillar in Utah is a bewitching prospect while climbing a building is a bedevilling one. But regardless of the unfolding quandary I'm going to the United States to at least attempt the climb. In a twist of fate the planned departure date is Quatorze Juillet, or the 14th of July, the French national holiday to celebrate the storming of the Bastille. I find the date quite fitting. As the French national anthem goes, The day of glory has arrived.

The first week in the United States is difficult but magical. I make my first trip to Utah, a most beautiful corner of the world. The state is a predominantly empty region of stark plains and purple sunsets. The whole day long I enjoy this wonderland, scrambling cliff sides in the abundant light of the brilliant sun above. I clamber up the rocks and survey the surroundings. Utah offers some truly impressive scenery. And some high temperatures: it is 43 degrees Celsius in the shade or, as our American cousins prefer to say, 110 degrees Fahrenheit. The cliff absorbs and emits heat like cast iron, but I keep fighting, sweat percolating from all the pores of my body. The climbing equipment can take it but the heat is so intense that I have to protect my hands with bandages to avoid sunburn. On the side of a rock I soon understand why the Native Americans have suntanned skin as strong and durable as leather.

The sweltering film crew, however, obviously cannot understand why we came here to climb in the scorching heat of the summer. Hey, this wasn't my idea, people. I am not complaining – I'm in my element. But it's not a time or place you would enjoy for long if you weren't a rock climber.

Cameras roll as I climb sheer cliff faces with ropes and climbing equipment. Safe rock climbing involves belaying, pairs or groups of climbers with equipment controlling the feeding of a rope to each other, so that any slippage means your companion does not fall very far. Being by myself I have to secure my own ropes. But I can also climb free solo – alone and without ropes, climbing with my bare hands with nothing to support me, nothing to save me should anything go wrong.

After shooting me abseiling down a cliff the director asks if I can climb this giant rock face solo. Of course he knows the answer to that question. The entire crew know that I live for free solo. I give them a little smile then up I go, doing what I am known for.

I ascend the rocks with nothing but my hands and climbing shoes, clutching at small irregularities in the rock face, inserting my feet into small cracks and grooves wherever I can find them, pushing ever upwards. As I pull myself further up the vertical cliff, the film crew shrink into the vast surroundings. There is no safety net, no rope. If I were to fall then it would all be over. Kaput. Violins. Some of the guys beneath me dwell on this and are obviously quite nervous. But I am not worried at all, as I have done this countless times before upon the French cliffs.

Not everyone can do it. It must be said that in most cases, climbers who have only climbed solo indoors in leisure centres find places like Verdon or Utah a good cure for constipation. This is also quite true for many observers. But for me it has always been exhilarating. I thrive in this environment. The rocks of Utah are cooperative and supportive, offering me plenty of grips and routes up their steep sides, plenty of options and variety. With this type of rock there's lots of resistance and very little chance of the grips crumbling away or, with the arid conditions, of me slipping. My hands and feet easily find grips and footholds and my audience below are stunned by my little party trick. The cameras zoom in with hushed excitement as I ascend higher and higher, pulling off increasingly difficult moves.

Being totally alone up here is the sweetest solitude, a blissful and tranquil escape. There is risk, of course, so it is not a relaxing type of solitude. But I find holding onto my life by my fingertips to be a sublime experience, an elating kick. Many might find the two emotions incompatible, but I would counter that it is quite easy if you place yourself in the right setting with the right attitude. Allsorts of sharp emotions invade me up there. It is difficult for me to explain the mix of wonderful feelings I experience when climbing solo in the mountains.

The film crew beneath me enjoy the show but as the days pass they soon become weary and the heat begins to wilt them. It is clear they'd much rather be filming somewhere with a bar nearby, somewhere serving ice-cold beers. I peer down every now and then to see them fanning their beetroot skin and wheezing, panting, swooning. Despite the uncompromising weather we get some superb images and the week is both a real success and a memorable diversion.

Our time in Utah concludes very nicely as far as the natural shots are concerned. But as we expected, or rather as we dreaded, no licence materialises for the urban shots. A crew member announces that we are up a certain creek without a particular piece of paddling equipment. What next? Am I going to have to climb on a mock-up on a film set, surrounded by green screens and technicians? Alas, the budget dictates no opportunity for this kind of whim.

Options limited, someone asks if I would agree to take the risk of climbing alone ... with the possibility of being arrested. The director seems most ill-at-ease with this request. He does his best to hold my gaze, like a poker player risking everything on a bluff. Big beads of sweat pearl on his forehead. His eyes try to hide his flustered thoughts but fail. Does he hold a flush or a pair of sevens? Naturally I want to learn more, so it's back to Chicago. If I feel okay, then I shall play my trump cards, on his behalf. But if I feel my luck is starting to turn then I will have to fold rather than lose my entire stake.

The director nods keenly and we fly to Chicago to hunt down a suitable building. He doesn't care which building it is, so long as it looks dramatic on film. I, however, need something that is possible to climb, something with ledges or protrusions that I can hold onto. And the search for such a structure is not easy. Skyscrapers are designed to suspend people hundreds of metres high on the inside, not on the outside. Soon I start having the same thoughts as I did when I first got here – it seems insane to attempt such a thing.

The corporate tower looms over me, all 48 floors of it. The tension rises a notch. Chicago is the city of Al Capone and organised crime and everything seems absolutely hostile. Security services will be after me, the police and fire brigade will want to get their hands on me. What will happen? I am scared by the prospect of being accosted by big angry security guys, or arrested by US cops, cops who carry guns and are not afraid to use them – not to mention the fact I might actually fall off a high rise building.

Over the course of the following days, I return there, alone, to study the structure, trying to feel the building, trying to imagine my movements, to estimate the effort necessary for such an escalation. I look around gingerly to check the coast is clear, then put on my climbing slippers. Without trying to climb the first few metres, I put my right foot on the grips to discover the touch, to tame it. I am amazed to find great interest in the slightest detail. My climbing brain starts whirling.

From the hotel across the road, I eye up my target with binoculars to find its faults, its weaknesses, the secret keys to my success. With no experience at all of such an ascent I am very uneasy about the prospect. Buildings are new territory indeed and are not my forte at all. In fact, no one in the world climbs them – you'd have to be a bit crazy to even consider it. And beyond the physical problems there's the law. Every one of us knows I am going to get into trouble with the American police. I have never been in such a situation anywhere, let alone abroad, and have no idea what will happen. Is it really worth it? I feel like an early navigator, about to embark on a global quest, torn between the temptation of adventure and the fear of losing my life. I am almost literally on the dizzying edge of a cliff.

I check in to another hotel closer to the Citicorp Citibank Center. In the meantime we decide to set the shoot for the following morning, to avoid the risk of the TV people falling into a judicial spiral which they stand no chance of escaping. Although these people seem to regard this procedure as normal, for me the latest line from them is a very hard blow. They will watch from a safe distance and get their documentary footage and I will be left to face the wolves alone. It weighs heavily on my mind throughout the day and I am full of doubt as I settle restlessly into bed. Where is the support I need?

The telephone rings at 7:00am sharp. I've been wide awake for several hours so I'm not pissed off to be called so early. Guess who? It's the desperate director telling me that there is nothing less than a full marathon organised at the foot of our office block. A marathon? This is a complete nightmare. Is it some sort of joke? How could this “small detail” have been overlooked? Thousands of pairs of American shorts will be bouncing along below the Citicorp Citibank Center under the eyes of an impressive police presence and ranks of race stewards. An escalation? No way. All bets are off while this citywide sports event is in progress.

I flop back on my bed, flattened by this ridiculous development. My phone blares out again. I answer it and listen to the latest hastily cobbled together plan. The director still wants to go ahead with the film shoot and the cameras will roll as soon as the streets are cleared. But when that will occur is anyone's guess.

It may be only a few minutes past seven but I am already exhausted by the day's events and I decide to try to get a little sleep. But after ten minutes I concede it is useless. I have far too much adrenaline coursing through my veins and lying there motionless is even more stressful. I spring out of bed and look for something to distract me.

Minutes pass slowly. I feel like a smouldering pressure cooker, and I need to expel my growing sense of stress and helplessness. Making hourly phone calls to my wife Nicole back in France is my only escape valve, my unique catharsis. Between phone calls I perform an endless series of push-ups, partly to warm up and partly to burn off agitation. I waste plenty of time.

A little before midday, it seems the coast is finally clear. We are free at last. Regrettably, the sky darkens and the first rainy drops spatter onto the panes. Merde! It's all off again. I can't climb in the rain since the surfaces will become slippery and dangerous, and the director won't film as he is looking for a clear and uplifting image, not a melancholy or moody one.

Distinctly wound up, I pace back and forth in my hotel room, to and from the bathroom, and peer out of the window every two minutes. Wait, wait, wait, we always have to wait ... Huffing and puffing I stride around and jump into yet another round of pumps. Usually, I would take this situation in my stride, but today serenity seems to have deserted me. After several hours of this I am fed up. Hoping for a nap I lie down. As a last resort, I channel-hop from one pointless TV programme to another, an exercise which, in the United States, can allow you to waste an entire lifetime.

My telephone wails out once again. By now much of the day is gone. The afternoon is dying but the sun bathes Chicago once more. The director, who seems to have lost some hair throughout the day, explains the latest development. He has just sent the film crew down to set up their equipment and I have to commence the escalation in less than an hour. Alexis the photographer will accompany me to the building in a taxi, then drop me off and depart for the heliport to take aerial images. The director asks me how long I think it will take to complete the climb. Short of benchmarks, I estimate the time of ascent at more than one hour; an hour and a half at most. He ends by sheepishly reminding me that the city fire brigade possesses a number of 60-metre ladders, a distance which I will have to climb extremely fast to escape capture. The call abruptly ends.

The first few metres of the escalation is negotiated in total alarm and with such haste that I cut my hands on rough edges of metal protruding from the building, a feature I had not anticipated. My movements are ill-timed and erratic, there is certainly no art to this diabolical climb. It looks more like a jailbreak than a professional ascent. In angst I race upwards in broken movements, fearful that at any moment a ladder with a burly fireman will spring up next to me and whisk me away.

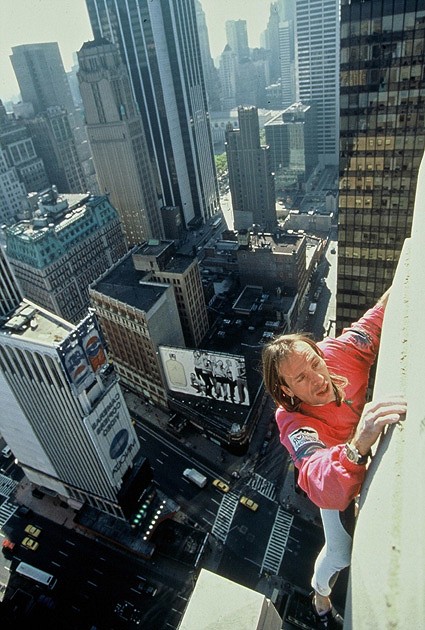

As I rocket further upwards I discover just how tough it is to climb a building. Steel and glass are nothing like any rock I have ever tackled at all and I have to adapt my movements accordingly. Worrying is the likelihood that my audience, usually fully behind me in my climbs, will this time be totally against me, seeing me as an outlaw, a crook, or a lunatic in dire need of a straitjacket. Furthermore, the intense reflection of the sun on the mirrored panes enhances the difficulty. I am like an ant scurrying around under a magnifying glass as the dazzling light seems to focus on me alone. But when I glance down for the first time, the ground below has already sunk away by more than a hundred metres. A true sprint! And much to my relief there is no fire engine.

With no ladders to worry about I turn my attention back to the building. On this pioneering climb, the difficulty results more from my inexperience, and from the incredible impression of imperviousness which emanates from such a building, than the movements I need to make. Up here, all alone, I am creating an imaginary hostile environment. The street drops away a little more with every movement, reminding me of the immediate violence of the penalty below should I make a mistake. This is a stressful climb, to say the least, and not much fun with all these unhappy thoughts bouncing around my head. I carry on for another 20 minutes, so focussed on my escalation that I had not bothered to look down and see a growing group of people gathered at the bottom. I find the same grips, push with the same movement and gain on the finishing line at the top. Technically it is very different to a rock formation but it is not extreme and towards the top I make better progress than I had originally expected.

And soon the top of the building, the summit of this urban rock, is within sight. I start to relax a little at the thought – it looks like I will really make it. Scanning around I can see no architectural obstacles near the rooftop as I close in on my goal. Finally I am within inches of the top. I place one hand over the lip of the summit and then the other. Cautiously I poke my head over the edge.

To my amazement a multitude of policemen, firemen and security guards await me. All this activity on my account is a bewildering sight. I pull myself over the top, not sure what to expect. Maybe it will be like one of those American cop shows? I expect at any moment a rugby tackle, guns drawn or the FBI to swoop in behind their dark glasses. Right now this is all very new to me, but I shall soon become used to this kind of reception. They all seem to be waiting for me to do something. Some reaction perhaps, some sort of cue so they know what sort of person I am and how to handle me. I break the ice with a broad smile and a greeting in shattered English with my thick French accent.

“Hi guys! Do not worry, I am professional rock climbeur. Zere is no mountain to be climbed in Chicago, so I decide to climb zees high rise! No problem! Everything is okay ...”

They cock their heads and frown. Neither side is quite sure what is going on. It looks like they do not really appreciate the joke, but still I feel no hostility. And it doesn't matter. What can worry me now?

The cops grab me by the elbow and I am under arrest. Arrest? I have never been arrested. But strangely as I am led away I feel a surge of accomplishment. Handcuffs, mug shots of my face from the front and from the side, fingerprints and – for the first time in my life – a few hours detained in a prison cell. But after these last days of fear and uncertainty, being locked up feels like liberation. This is a great achievement for me, make no mistake about it, especially since a few years earlier the doctors had condemned me to remain nailed to the ground, after two successive falls in the mountains led to crippling multiple fractures.

Without realising it, the direction of my life had changed dramatically and irrevocably. This day would be the one that would help define me. Little did I know it, but the city of Chicago had just opened a door to a whole new universe ... a range of mountains of glass and steel.

Comments