From the death of Pakistani porter Mohammad Hussan on K2 as over 100 climbers filed past him to the current financial crisis at the BMC, much has happened recently in the climbing world and it all comes down to money and numbers, argues mountaineer, author and former Alpine Club President John Porter.

Victorian writer, cultural critic and lover of mountains John Ruskin once said that the alpinist of his age had 'turned the cathedrals of the earth into a race course.' Most traditional mountaineers now feel the same way about the races to complete the fourteen 8,000m peaks, and all the other 'mountain speed records' that look 'good' on a CV: the quest for the seven summits, the quest for the second-highest seven summits, and so on. Commercialism in mountaineering has taken a dangerous, nihilist and spiritually transcendental pastime, and flattened it into neutered commodities that can be sold as mountain tourism adventures.

It seems a new set of demons now inhabit the mythical heights who are very different from the trolls and dragons described in pre-Romantic concepts of the creatures lurking in the mountains; in other words, humans are now the terrors.

To begin with, consider the impact of money on climbing as whole. For any business to make money, it requires a market, and to get a market, you need to grab peoples' attention. At one end of mountaineering marketing is the ability to sell 8,000m summits, especially Everest. At the other end, is the development of a personal brand that can be sold to the public as an achievement—for example, Kristin Harila and Tenjin Sherpa's race to climb all fourteen 8,000m peaks in a record time of 92 days.

Mountain tourism on the 8000ers involves little or no technical climbing skills apart from going uphill. These are 'via corda' ascents, like via ferrata, but metal is replaced with ropes strung by high altitude workers. The often very competent and fit Sherpas and high-altitude workers provide the tourists not only with some sense of being safe, but they carry supplies and equipment to each camp— including supplementary oxygen to keep clients comfortable (and alive) at altitude. They do the thinking and planning for you.

Some high-altitude workers can make a relatively decent living, but some are exploited and lack the proper training and/or equipment. Certain expedition operators are neglecting their duty of care for high-altitude workers in order to offer budget experiences while boosting profits. Expedition clients, too, can overlook their worth. The recent tragic death on K2 of Pakistani porter Mohammad Hassan - an inexperienced and under-equipped porter on an overcrowded mountain, whose rescue needs were sidetracked by a systemic, single-minded fixation of dozens of people on reaching the summit - should make us hang our heads in shame.

27-year-old Hassan, who died above 8,200m on K2 on 27 July, was trying to earn enough to pay for his mother's treatment for diabetes. Upon becoming incapacitated after a fall, he was passed by a line of around 150 people as he lay dying. One report states that Hassan had no down suit — an essential piece of clothing for ascending an 8000er.

Although Kristin Harila's team and others have since claimed that they assisted Hassan and denied calls of neglect, the situation raises the question as to why the mass summit push was not aborted and instead prioritised over saving the life of a fellow human being.

Aside from the danger that increased money and numbers can bring to mountaineering, it seems to me that the modern culture of mountain tourism has also commodified a human endeavour that should bring people closer to an understanding of nature—the unique experience provided by the rarefied and delicate environment of the high mountains.

Mountain tourism is just another example of how we say one thing about protecting the planet, but do the opposite. It sets a terrible example for coming generations. Kristin Harila and Tenjin Sherpa no doubt set a record for the quickest completion of the fourteen 8000ers in just 92 days - aided by helicopters - and also likely set the record for the highest carbon footprint by a pair of climbers in the shortest period of time. It must surely also rank among the most expensive mountain projects: Harila told the press that the project cost more than £1.1 million—a 'peak package' that can now be sold to those who can afford it like the growing market for short flights into space.

***

It's true that commercialisation and competition in mountaineering is nothing new. During the Golden Age of Alpinism, contenders raced to climb all of the highest mountains in the Alps. At that time, and for a century afterwards, a mountaineering 'first' was the most important number; first to reach a summit, first to reach the summit by a new route, first solo, first enchainment, first multi-peak ascent, female, youngest, oldest, disabled and so on. In the second half of the 20th century, nations spent considerable money in the race to be the first on all 8,000m peaks.

But the sums of money then were tiny compared to the sums that drive mountaineering 'sports' today. The marketing opportunities to target the wealthy and make money from the mountains - by offering package and even 'luxury' expedition experiences, some of which cost around £100,000 - are too obvious. To the general public, climbing Mount Everest appears to be a remarkable achievement. Few appreciate that if they had the money and a reasonable level of fitness, they too could 'conquer' Everest. The idea that humanity can 'conquer' any part of nature makes true climbers wince. As George Mallory said a hundred years ago, 'the only thing you conquer is yourself' – the very opposite of the current self-branding trend.

I would argue that Harila's race around the 8,000m peaks is a modern echo of that 'Golden Age of Alpinism.' Whymper won the race on the Matterhorn but at a tragic cost of four lives. Harila and Sherpa's achievement is now tainted with death, regardless of the circumstances. To some extent, mountaineering has yet to mature to an age where it is totally removed from number crunching.

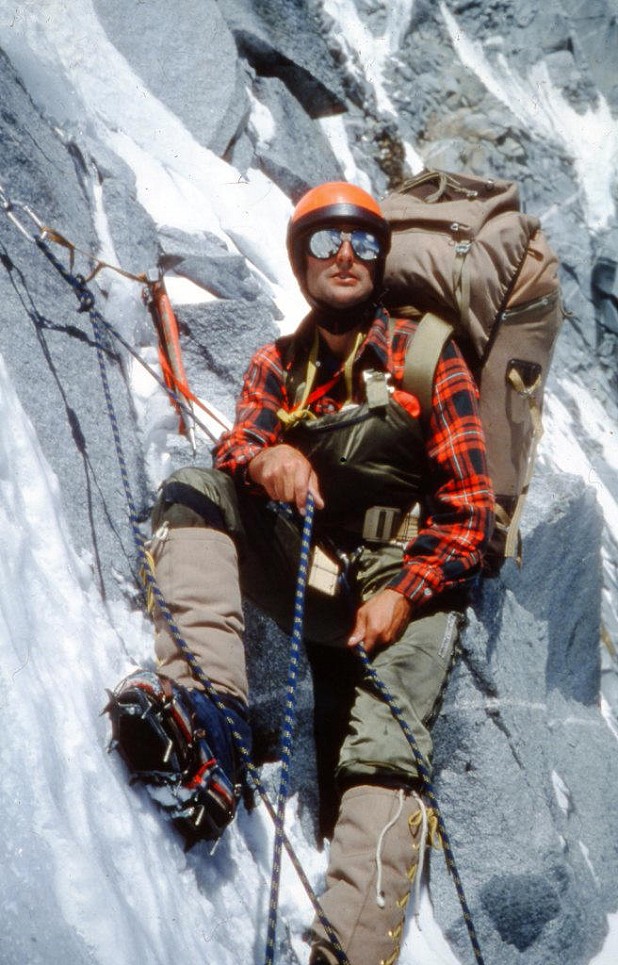

Some of the damage being done by mountain tourism is more subtle. The over-generalisation of the word 'adventure' has diminished the real value of taking risks; i.e. testing our limits. The majority of the climbers in my generation could be described as outliers - rebels, nonconformists, eccentrics, bohemian dissidents, dissenters and iconoclast heretics. To me, they were comparable to the dandy poets of the 19th century and the underground artists in 20th century; the jazz musicians and rock and rollers driven by atavistic and basic motives to create something different.

Social media can lead to the delusion that everything can quickly be grasped and mastered. But my generation spent thousands of hours in the mountains developing the skills and the experience that fosters a mountain sixth sense, and an ability to better understand the risks. Then as now, on major first ascents, risks were taken. Many died in the mountains as Brian Hall's harrowing Boardman Tasker award-winning book High Risk explains.

***

Ken Wilson, a revered climbing writer and editor and my boss at Mountain magazine, once suggested to me that the likelihood of nuclear war turned alpinists towards seeking an individual fate. My personal view is that we were driven by a need to explore, to touch places and moments that were ours alone. In so doing, we were like artists, creating a path, an echo of the art of Richard Long's 1967 A Line Made by Walking. So, the first point in my argument is that in many ways, alpinism is closer to art than it is to sport.

Let's play a game of 'spot the odd one out':

a) World Cup Climbing Competitions

b) Alpine climbing

c) The World Badminton Championship

d) Kristin Harila and Tenjin Sherpa's 14 x 8,000m peaks race

Of course, the answer is alpine climbing. The others are all sports, and alpine climbing is not a sport.

Unlike alpine climbing, the other activities all have time- and rule-based results; win, lose or draw. These are the characteristics of all sports. Results are ruled by numbers – who is number one, number two, etc. They can be compiled into tables: wins, losses, runs scored, medals won, and so forth. By now, some of you will be saying: 'Hold on, what about alpinists claiming first ascents? Isn't that what alpinists do?' True, being first becomes a sequence of ordinal numbers, and many people get excited about being first. But those who do the second, third or whatever ascents that follow are likely to have very different experiences from the first ascensionists, and that's the point. Alpinism is primarily about the adventure and the experience, not the number.

'And what about the Piolet d'Or awards?', you might ask, since they recognise achievements in mountaineering. 'Isn't that moving toward creating league tables?' Yes, perhaps, but the judges have side-stepped the issue by awarding the route, not the individuals. The ethics and style of the ascent is what counts for the Piolets d'Or. The 2021 Ukrainian ascent of the SE Ridge of Annapurna III was brilliant, but the climb was not awarded a Piolet d'Or because a helicopter was used to reach basecamp, and later, to evacuate. Some say that was harsh on the team. Everyone will soon be using helicopters to reach climbs, especially with glacier deterioration. To me, helicopter use diminishes the experience, adds to the CO2 footprint, removes the need to communicate with locals, and takes economic benefits from the overflown communities. If flying is necessary, why not paraglide like Will Sim and his team? Most lifelong alpinists appreciate that the journey is often as rewarding as the climb, if not more so.

My good friend Voytek Kurtyka, the eccentric and visionary Polish mountaineer, was the first to suggest to me that humanity lives under a tyranny of numbers, that our spirits are captured by a fascination with figures and statistics, driven by what society expects. Achievements are measured by numbers - salaries, speed, MPG, distance, batting averages, power ratios, etc. For rock climbers, that translates into V grades, E grades, nuances of 6a, b or c. When a climb's grade is set, number 1 appears again: first head point, pink point, red point or solo.

Applying measurements to mountaineering is more difficult. It is a very old debate. At the first Olympic Congress in 1894, the possibility of including mountaineering in the Olympics was considered, but dropped when it was realised that mountaineering achievements happen in different environmental conditions, altitudes and difficulties that vary from peak to peak. The pursuit does not take place in a homologated field of play as in a running race or many other sports.

In competition climbing, athletes perform on manmade structures and try to win results, as in any other sport. The BMC management have become so enthralled with the possibility of medals that, without the knowledge of the membership, they have for the past two years drained the reserves to pay for massive overspends by GB Climbing, including their decision to host the IFSC World Cup in Ratho last year. The BMC CEO Paul Davies subsequently said that he thought this was 'good value' because it only cost each member - many of whom have no interest in competition climbing - less than £3 each. It was a strange 'business' decision to plan to make a loss of many tens of thousands of pounds—ending in a £90K loss in total; another small deception driven by the tyranny of numbers.

***

In this 'fast-food' fixation on commodification, consumerism and competition, something of the philosophy of climbing and mountaineering has also been lost. Peak bagging can become an end in itself, a joyless number-counting exercise—unless each moment is lived. Late British mountaineer Paul Nunn said: 'When we go climbing, we put one foot in front of the other, go as far as we can, but always remember that the return journey requires the same effort, foot by foot.'

Is it just me, or is it hard or impossible to detect this sentiment among the selfie-obsessed peak baggers? As a result, we find people stepping over the dead and dying in the mountains because they have paid 'good' money to get to those heights. It has always been thus: where there is money to be made by people in charge, and some people are willing to do pretty much anything to make a living, values are stripped and minimalised. In other words, little concern is shown either for nature or humans.

But is this different from behaviours in any other human activity? I don't believe it is, and as they say: it takes all sorts. I believe every human has the capacity to learn and change. The flip side of the Mohammad Hassan story is that it has drawn public outrage and. I suspect, some 8,000m peak baggers may be thinking about their own motives and values.

It could be said that we mountaineers who have written books, given lectures and appeared at festivals are hypocrites since we are all complicit in the chain of history that has led to where we are today. Where did it start? With the first ascent of the Matterhorn? Or was it the 1953 ascent of Everest? It is the world's highest place, a symbolic pinnacle and inspirational to more than just climbers; a bit like being the first to the moon in 1969, a human achievement regardless of which nation was first. What is very different today is that the idea of 'conquest' still reverberated in a 20th century marked by destructive world wars. I ask: what today does man need to 'conquer?' Mallory has already given us the answer – our egos and delusions.

It is high time for our aspirations to mature if we are to survive the anthropogenic impact on our planet. For many alpinists, the only numbers that count are the years they can spend in the mountains, learning about the fragility and the beauty of life in nature. It is a counterintuitive truth that alpinism reduces stress in our personal lives by enhancing our awareness of existence, its fragility, our limits and our insignificance. Competing for numbers adds stress and might destroy us all.

Kendal Mountain Festival 2023

John Porter - A Path of Shadows - Saturday 18th November 9 p.m.

Well-known to our audience as one of the founders of Kendal Mountain Festival and Director of the Festival until 2008, John Porter is also a renowned mountaineer with many first ascents in the greater ranges. He is the award winning author of Alex Macintyre's biography 'One Day as a Tiger', a founding member of the Mountain Heritage Trust, has served as president of The Alpine Club, and is currently secretary of the Mountain Everest Foundation.

This lecture is a biographical record of the inspiration the author has found in over 60 years in his pastime of mountaineering and mountain culture, thinking through his varied life, exploring the natural world, physics, the threat of life's extinction and family ties around the world. John's book 'A Path of Shadows' will be available to purchase at the Festival book store over the Festival weekend.

Visit the KENDAL MOUNTAIN FESTIVAL SITE.

- ARTICLE: A Path of Shadows – John Porter 31 Aug, 2022

- REVIEW: The Art of Freedom by Bernadette McDonald 22 Sep, 2017

Comments

Well said.

Some years ago, I received some badly-targeted advertising on my Facebook feed from the Bear Grylls survival school about their 'Survive Snowdon!' course. Whilst the focus of my subsequent rant about was on the use of our domestic environment rather than greater ranges mountaineering, I ended up at much the same point as John has in this piece. Excitement and adventure in the most dangerous places of the world comes at a greater financial and environmental cost, but also at a potentially greater personal cost for both the purchaser and enabler.

Anyway the crux of my Facebook rant from four or so years ago is below. I still hold the same view.

T.

"But it isn't that which grips my shit . . . what it is, is the way that 'experiencing' the hills, and the outdoors generally, is being hyped up as Big Challenges. This 'survival school', the Ben Nevis/Scafell Pike/Snowdon three peaks, the Yorkshire three peaks, amidst much else. It's all 'hey wow, look at me', all about 'conquering', 'surviving' and many other such words ending in -ing. The people who do these things probably say that they are 'awesome' and that they 'smashed it'.

For heaven's sake. What would be awesome is if they learned a bit more about respecting the environment, about not behaving like accident statistics waiting to happen, about how putting yourself under pressure to achieve something in the outdoors can come at a cost of failing to do it, and then having the respect for the environment and for other people to get yourself out of the mess you've got yourself into.

I know, I know; everyone has their own Everests and what might once have seemed routine to me may count as a lifetime achievement to someone else. I don't frown on things for that, it's just the sense that some of our most valued landscapes are being treated as a casual commodity, and that people are paying money to use them on that basis."

Very thoughtful article John. Feels like this should have been written about more / before now. Thank you for writing this.

I read a related article in the Guardian and few days ago on the tourism that has been carrying on in places that have recently suffered from environmental disasters, (Rhodes, Maui). Tourists have been continuing to holiday on the beaches and swimming in the same waters that folk have just died in. And, as the journalist puts better than me this dissonance goes to the heart of the contradiction of our modern and unsustainable lives - and that includes many of the aspects of alpinism you describe.

The article is here: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/aug/30/tourists-rhodes-maui-burned-travel?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

Whilst I share much of John's opinion regarding high altitude mountaineering, I can't help but feel there's a bit of elitism creeping in, with sentiments such as:

"Peak bagging can become an end in itself, a joyless number-counting exercise"

It's not for us to determine what is and what is not "joyless", having seen for myself the joy and camaraderie experienced when someone competes a round of Munros, Wainwrights, Seven Summits or whatever.

I think it's important to let everyone enjoy the outdoors and find their own connection to the mountains in their own way, when it does no harm to anyone else or prevents the rest of us finding a more spiritual connection if that is what we are looking for.

A long while back I moved away from bagging summits and instead explore the less visited areas either side like hanging corries, subsidiary ridges etc. I do the same to a certain extent in the Alps and Dolomites and bigger ranges. Not a Tillman I’m not treading in unmapped terrain, though tracks are few and far between and the going can often often slow if it’s technical. But it can be delightfully quiet if you are exploring routes in and around the mountains that don’t actually lead to a summit. It’s been liberating, once you let go of the idea of having to reach the summit of every mountain you step upon the slopes of.

As someone slowly working my way around the Munros I agree. Yes I do occasionally do a hill just because it's on the list and I do undoubtedly miss some fantastic hills because they are Corbett's, but I have made friends on my trips, it has given me a consistent destination for my holidays that gives me great joy, it has shown me some fantastic mountains that I would not have visited otherwise.

I have had a couple of cruddy days on Munros, but I reckon of the 50 or so days on the hill, only one was particularly devoid of redeeming features (Ben Teallach or the one next door on a rather horrid day where my boots started to leak.

It has also helped me get to know the Highlands as it has taken me all over and I appreciated the knowledge when I cycle toured through them a few years ago.

I think it's really about taking time to savour these places that speed challenges lose out on.