Toby Dunn relives some of his finest, unusual, and sometimes disgusting food choices on climbing trips over the years.

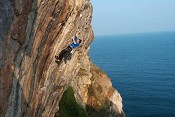

That first experience, in a café, a restaurant, or a shop when you're somewhere new is often when it really hits you that you're somewhere else. In essence, climbing rocks isn't radically different from one place to another. OK, you're not in the UK, so the rock might be better, the crag bigger, and the weather could well be more pleasant and less changeable. But halfway up a route, the microworld of your concentration is the same maze of crimps, slopers, and pinches which you must connect with your available strength in order to keep yourself in the game.

When you go out for something to eat, though, and a bloke you don't understand tries to sell you something unidentifiable, you know you've arrived somewhere else. This might be in South East Asia, and you might be encouraged to try a delicious frog from a menagerie of currently living specimens in a tank in a café window; or indeed it could be just across the Channel, where you're offered a sausage with a deeply suspicious, strong whiff of having recently been an essential part of the insides of an animal of some sort. It's a way into a rich variety of experiences, memorable for good and bad reasons.

The most horrible cup of tea in the world: Alpine Climbing in the Southern Alps, New Zealand

A year after starting to climb, and just after leaving school, a schoolmate and I scraped together enough money to fly to New Zealand for nearly six months. Our choice of destination and many of the details of our trip seem completely bizarre in retrospect, yet I wouldn't change anything about it.

On our extremely limited budget, and with the aid of a raucously loud petrol MSR stove, most of our food consisted of huge quantities of extremely basic food. We were hitching or walking everywhere with huge 100L backpacks, filled with kit for everything from alpine plodding to bouldering. Aged 18, we seemed able to eat almost anything without regard as to its nutritional benefit or effect on our bodies. On a number of occasions, on extremely amateur alpine forays into the Southern Alps, we sustained ourselves in the long, bitterly cold evenings on a big pan of pasta. The pasta was 'flavoured' with a couple of small catering packets of butter, salt and pepper which we'd nicked from service stations or cafes, or occasionally a cup-a-soup packet. We'd usually drain the pasta water, once the pasta had been thoroughly overcooked, into our plastic pint mugs, and make what I'd optimistically describe as tea with the cloudy, starchy liquid. I can still remember the unique flavour and appearance of this brew more than twenty years later. We survived almost exclusively on this pasta, packets of Anzac biscuits, cheap cakes, and occasionally takeaway fish and chips, for several months. I have no idea how we did not acquire scurvy.

Bread and dubious sausages: Sport climbing and bouldering in France

While I was at University, I regularly indulged in the climbing student cliché of piling far too many people into a tiny, borderline legal car and driving to France to camp in the free campground near Barbizon, Fontainebleau. Fortunately, the marvel of France as a bum's climbing destination is the universally cheap, infinitely versatile baguette of at least reasonable quality, on which many a meal was based. Any vehicle or rucksack that anyone owned would become infested with the shards of baguette crust, which you'd then find months later while back at a crag or when driving at home, like a surprise memento of your travels.

Sometimes, on a longer holiday period, we'd go to the sport crags in the South, where the evening meal often consisted of one of those 'value' range huge tins of cassoulet or sausages and lentils. On return to our campsite, the contents would be tipped into a pan over a camping stove in a single slippery mass which would exit the can with a disconcertingly faecal squelch, and then be broken up with a spoon in the pan. This was usually barely heated through before being distributed among however many people were present, and consumed rapidly with the remainder of that day's baguette and cheap, warm lager. The chunks of meat in these cans were profoundly dubious, but after a long day of climbing, and a beer or two, it certainly tasted good. It probably helped that it would inevitably be eaten in the dark, and we all had only slightly knackered old Petzl Zoom head torches, so fortunately you'd never actually have to see what you were eating properly anyway.

Ensaimadas and tinned tapas Russian roulette: Sport climbing and bouldering in Mallorca

I had several friends who did language courses at University, and their year studying abroad was usually used by me and others as a free hostel in a sunny climbing destination with cheap alcohol. We often went to Mallorca in the winter, to find sunny rock and cheap alcohol. On one trip, myself and a mate had stocked up on food and alcohol before the long holiday period in which all the shops would be closed. Our supplies were crammed into the boot of our car, and we headed off to a sunny sport crag for a day of climbing in shorts in January, trying to acquire a tan to take home. We got back to the parking area tired and hungry and discovered the car had been broken into. All of our provisions were gone, along with about half of our possessions. We proceeded to have to subsist for several days on only what one could buy in all-night petrol stations in rural Mallorca. I can attest that a diet of crisps, litre bottles of San Miguel, and plastic-packaged ensaimadas (a sugary cake sold everywhere on the island) is not conducive to climbing very hard.

After this, the trip turned into a search for a slightly more comfortable life. We managed to scam a floor on a plush flat owned by friends of friends in Palma. They took us out bouldering with them to a 'locals' coastal destination of extremely good quality. Sick of the monotony of standard crag food, we took as many different weird looking tins of seafood as we could find in the supermarket and a loaf of bread to the crag, to fuel us all for the day. To add interest, we dispensed with all of the boxes, so that you never knew what beast the tiny containers of briny tentacles contained. I still have a particular taste for those little metal containers of squid in its own ink, octopus in some sort of spicy tomato goo, or hundreds of different varieties of clam in delicious mini baths of brine.

Cheesy pancakes, cheesy pies, and huge chunks of meat: Alpine rock in the Polish Tatra

One of my friends discovered that the cheapest way of going climbing somewhere interesting for the summer (this was before very cheap air travel) was to purchase a one-way coach ticket from London to Krakow in Poland. This didn't seem to be too far from the Polish Tatra mountains.

I tried to learn a few words of Polish, and became moderately proficient in the phrase which means, 'Sorry, I don't speak Polish'. This was perhaps the most useless thing I could possibly have learnt, as this was abundantly obvious to anyone with whom I tried to make conversation. Our linguistic idleness was penalised when trying to order food; we usually ate out or bought street food as it was so cheap at the time. I once ended up ordering what I'd correctly guessed were pancakes for breakfast on one occasion. Unfortunately, what I'd not guessed is that they were savoury, and smothered in an intensely rich cheese sauce with a powerful tang of sheep or goat to it. This was not exactly what I had in mind, being used to the typical sweet Western breakfast cereal-based fare. One of my friends, trying to buy food to take up to the mountains for a few days, bought a bag of what he'd thought were pies, with which he was extremely pleased with until he bit into one and discovered that the brown, fist-sized, textured lumps were not the tender meat encased in crisp pastry of his dreams, but bumper-sized smoked cheeses, again with a powerfully acrid ovine tang to them.

We travelled around some of Poland and the Czech Republic on the cheap, trying to find climbing; this was sporadically successful, but we tended to get distracted by the attractions of taking advantage of being able to eat and drink out for a pittance. Unable to understand any menus, one of my friends noticed that all of the meat options had a weight measure next to them, and merely ordered whatever was heaviest. On several occasions, he was served what appeared to be a sizeable percentage of a pig, cow or sheep, usually with no other adornment to distract from the huge chunk of meat, gristle and bone. It seemed that Zwyiec (very strong Polish Lager) was regarded as an acceptable substitute for any carbohydrate or vegetable with the meal.

Big burger world: Sport climbing in Colorado, USA

The USA is separated from the UK by far more than an ocean. No one told me, before I first went to the USA, how profoundly different it is to Britain. I think I'd assumed it was going to be a lot bigger and brasher than the UK, but otherwise, at least people spoke the same language and seemed pretty similar. I find the States constantly fascinating, but totally alien. It has always struck me that the USA feels more different than the numerous parts of Europe or Africa which I've scummed around. American food is perhaps the best example of this. I had a prejudice that it was all huge portions at gross chain restaurants, or at diners with booths and bench seats serving vast breakfasts of meat, pancakes, eggs and hash browns all smothered in maple syrup, washed down with unlimited coffee.

I had become vegetarian at home, but this was completely destroyed by an initial summer trip to Colorado. I was sufficiently dim not to realise that the US is stuffed with utterly delicious, meticulously prepared food of almost infinite variety as well as the global fast food chains. We'd spent a day climbing at Shelf Road, which was totally unremarkable other than for the number of rattlesnakes that lived there, and the number of times my American friend had enthused about the quality of a burger place near there.

Starving after a long day at the crag, and giving in to this relentless enthusiasm for the post crag meal, we drove in the dark to a large pullout by the road on the outskirts of the nearby Canyon City. The lonely layby was lit by yellow arc lights. Canyon City houses six high-security prisons, and not very much else, and the whole area had a hot, bleak feel to it. In the layby was a large silver trailer over which was a large, slightly faded sign, proudly proclaiming it as 'Big Burger World', as though it was a Disney-style theme park. From the trailer were disgorged burgers of comically bulbous proportions, and with numerous adornments. My vegetarianism was instantly discarded, as I consumed what is still by far the best burger I've ever eaten.

Day glo macaroni, and an ice cream sandwich: Tuolumne Meadows and Yosemite

The 'dirtier' side of the climbing dirtbag's diet in the US is instant mac 'n' cheese, which was often our staple diet on long cheapskate trips. The macaroni was quick and easy to decant in a dusty, odorous neon shower from its packet into a steel cooking pot of steaming water, briefly heated before being consumed with mouth-scalding haste at the end of the day. It always exhibited a really disconcerting ability to absorb liquid. There seemed to be no limit on how much water you could bring to the boil, a packet of the tiny dried macaroni noodles and dried 'cheese' stuff would quickly absorb the lot and form into a bulging dayglo lump, like the villain of a 1950s horror B-movie heaving ominously in your head torch beam. The result was certainly filling but probably had absolutely no nutritional benefit whatsoever.

The first thing I ate the very first time I went to Yosemite Valley was as peculiar to me at the time as seeing a pickup truck driving around a town with what appears to be a rack of machine guns strapped to the back of the cab. We were climbing in Tuolumne Meadows as it was the height of summer and Tuolumne is higher and cooler than the Valley. My American friend insisted on driving down to the Valley one evening after a day's climbing. The Valley was still uncomfortably hot and sweaty, although it was late in the day. On my friend's insistence, we went straight to the store in the Valley, when all I wanted to do was gawp at crags. In the store, he purchased two large black cans with gold writing; 'King Cobra', and, from a cavernous freezer, two oblong packages inscribed with the simple but baffling word 'ItsIt'. The booty was taken at speed to El Cap meadow, and we sat in the long, dry grass, consuming the sandwiches of sweet ice cream between two crunchy, equally sweet cookies. They were washed down with the warm, extremely alcoholic, malt liquor in the cans. If you haven't been to the States, and haven't tried malt liquor, it's a little like a very cheap super strength lager, only worse, and possibly stronger. As I lay back in the grass, gazing up at the most impressive, inspiring looking crag I'd ever seen, the King Cobra was the best thing I'd ever tasted.

The worst pork scratching in the world: Thailand

Deep fried pig tendons are the best way of explaining what South East Asia is like to anyone who hasn't been there. It looks fascinating, you feel drawn to have more, despite feeling simultaneously like all you'd like is to be somewhere familiar and eating something normal.

The relentless heat and humidity, numerous and aggressive insect life, noise, and confusion are addictive and fascinating. At the same time as they made me long to feel even slightly cold, drink a cup of tea, and wear something more than a vest and board shorts. Tonsai is a unique climbing destination in that you don't ever prepare, or buy your own food to prepare, or even brew a cup of tea yourself, as it is so easy and inexpensive to eat in the numerous tiny shacks-cum-cafés by the beach. It's not really necessary to take any food to the crag either, other than perhaps a couple of bananas, as you can often walk less than a hundred yards down to one of the eating places for some Pad Thai or a delicious curry.

My favourite rest day activity, to get away from the Phra Nang Peninsula for a day, was to take a boat to the mainland and go to temples or street markets, each one a baffling maze of noise, colours, and smells. In the markets, dodgy-looking trestle tables groan with profoundly strange looking and smelling fruit and vegetables. Stall holders shout unintelligibly at you as you wander past. The stallholders manhandle vast cooking pots and woks over extremely powerful and unsafe looking burners. On one visit, a friendly stallholder convinced me to try what they were preparing. They beamed as I bit into the brownish craggy morsel that they handed over. It was somewhat like biting into a leather belt, with a very vaguely meaty scalding greasiness to it. 'Fried pig tendon', they proudly announced with a beaming smile as the chunk burnt the roof of my mouth. I wouldn't recommend what is much like the worst pork scratching you could possibly imagine, with the potential to inflict third degree burns to most of your upper digestive system. I didn't know whether the evident satisfaction of the cook was because they were actually proud of their creation, or amusement that they'd got a tourist to eat something that was meant to be fed to animals, or used as a weapon.

I developed an addiction to Som Tam (a shredded green papaya salad) and Gaeng Som Pla (sour fish curry). I'd had simulacrums of these dishes in restaurants in the UK, but nothing like this. I loved leaving the crag, tired and possibly still pumped as they were so close by, and ordering the som tam to see the cook putting a pile of papaya, chillies, tiny dried shrimp, lime, herbs and peanuts along with a few other things in a vast pestle and mortar before smashing it all into an amalgamated mass with an enviable amount of energy and strength. It constantly amazed me that subjecting an assortment of things to such extreme violence somehow resulted in the brightest, freshest, most amazing tasting thing I'd eaten in my life.

Malt loaf, flapjack, sandwiches, and the occasional exploding chicken: The Great British crag snack

A great friend joined me once for a frigid midwinter day bouldering at Almscliffe looking very pleased with himself. He'd decided that the best way of sustaining himself in the cold was to buy an entire rotisserie chicken and to gnaw on it in a bestial fashion at regular intervals all day. As the sun began to set, and our skin wore out and arms tired, he'd managed to strip it down to an almost bare carcass. He then proceeded to walk to the top of the crag and, with great ceremony, drop the remains of the chicken onto a flat piece of rocky ground and watch it explode into hundreds of pieces. I'm deeply uncertain about the wisdom of his choice to fuel optimum climbing performance, and I certainly wouldn't condone throwing food litter around, but it's a great memory of a great and much missed friend.

- ARTICLE: Room 101 - Toby Dunn's Worst Climbing Experiences 9 Feb, 2021

- ARTICLE: Toby Dunn's Desert Island Routes 14 Dec, 2020

- ARTICLE: Close to Home - Climbing & Travel in a Post-Pandemic World 9 Oct, 2020

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Gorges de l'Aveyron 1 Feb, 2019

- ARTICLE: Helmets - Keeping a Lid on it? 31 May, 2017

- ARTICLE: Like I need a Hole in the Head 8 May, 2017

Comments

I enjoyed this. Most entertaining, and I don't envy some of the food choices!

Good article. I look forward to a 1980s nostalgia piece about surviving a weekend of Clachaig bridies and late Sunday night fish supper from the Ben Fong.

My first Andouillette and Tete de Veau in France are seared into my memory, (in a good way, I've had many more since) and I'll never forget the first pork shoulder in Spain that was bleeding all over the plate; "This is how we eat it." It's how I eat it now as well.

I enjoyed it too, like all the pieces by Toby I've read so far.

Thank you very much for the appreciation, I enjoyed reading the experiences above as well. I think that everyone has eaten some pretty interesting things on climbing trips, good, bad and truly repulsive.