Jonny Ainslie shares what it means to have an adult life transformed by climbing, to find direction and move from London with limited outdoor climbing to the heart of the Peak District.

Climbing in the Peak District has pedigree, and it often feels like the climbers here do too. But although I live here, I grew up in a commuter village where the only crags on UKC for 50km are the undersides of bridges. I hardly knew what climbing even was until a girl I liked suggested we go see that obscure indie film, Free Solo. I was twenty-two years old.

This is, undoubtedly, the world's most annoying origin story for anyone trying to persuade anyone that they're a real climber. For years I've been one of those 'newbies' cluttering up your gym, asking people whether there's much sport climbing at Stanage. There are no blurry polaroids of me toddling on a boulder in nappies, or top-roping with a parental hero to teach me how to fall.

I never had idols – no superhumans I wanted to be like; and this only makes sense now because I hadn't found Moffat, Moon, or McClure. Couldn't have had posters up of Lynn Hill on El-Cap, let alone Ondra or Janja. When I climb, I'm missing any sense of eternal return; I am always going somewhere I have never been before. And while this might sound adventurous, it often makes me feel like an outsider on the fringe of a very exciting club. But I'm here, living and working and climbing almost every day in the Peak District, and it's changed my career, friendship circles, diet – everything. Even though people might always see me as new in town, I don't feel lost anymore. Let me tell you how that happened.

From about the age of six, movement was hard work. PE teachers with whistles, stopwatches and very hairy legs made movement all about Sports: things that I had to win. To which I said: "I'm asthmatic". It was true that, occasionally, lying in bed on my side felt so difficult that I couldn't move or think of anything other than trying to drag air deeper into the tight wet sackcloth of my lungs. But even when I had my inhaler I was losing, was in pain, while the exertion seemed to warm the other kids with a vigorous joy I knew nothing about. So I chose to be goalie where I could stand still, and then did badminton, which was inside, and finally I just stayed in the library. In there, I could escape from the confines of my body, and travel through fantastical places without breaking a sweat.

It is my suspicion that many children have a similar relationship with movement today, and that it risks hindering how they might learn through practice to be in their body, to love their body, or start to be present in the flow of their muscles and in our world. That's what happened to me. My hobbies were almost all sedentary retreats, and so was my education, and so was my work. While graduating to London and getting a job made me impressed with myself, I'd learned not to pay attention to how it actually felt being a body. Being sedentary makes you sleepy, makes it harder for your brain to modulate serotonin and dopamine, increases feelings of loneliness, anxiousness, without even getting to the long-term health implications.

So, it seems inexcusable that less than half of British children ages 5-16 get the recommended hour of physical activity a day (this includes walking), and 30% of them do less than half an hour. Only 63% of adults manage 2hrs30mins of exercise per week. When you can't be a body, and just run, or breathe, or climb, you're also particularly susceptible to letting your mind limit your experience of the world. The buzz of thoughts and self and ego had always been there, my constant commentator and critic. Until I watched Free Solo, and it made me feel – madly, unjustifiably: that's for me.

Pulling on sweaty rental shoes in my street size, I might as well be bowling. But hanging from the finishing jugs feels like I'm dangling from a rooftop made of sandpaper, lost in clouds of chalk. I plant my feet from toe to heel on the volumes, and somehow I still slip. Flat on my arse, my palms are stinging like they're being thoroughly iced. And yet I stay: ripping flaps of skin from the meat of my fingers until they start to weep clear fluid and blood, and until I forget that it hurts. It didn't matter that there were six-year-olds lapping me – in fact, I can see how much fun they're having. How much fun I'm having. And although climbing picked me up in its cultural moment, it also provided so many of the things my body was missing, and I clearly wasn't alone.

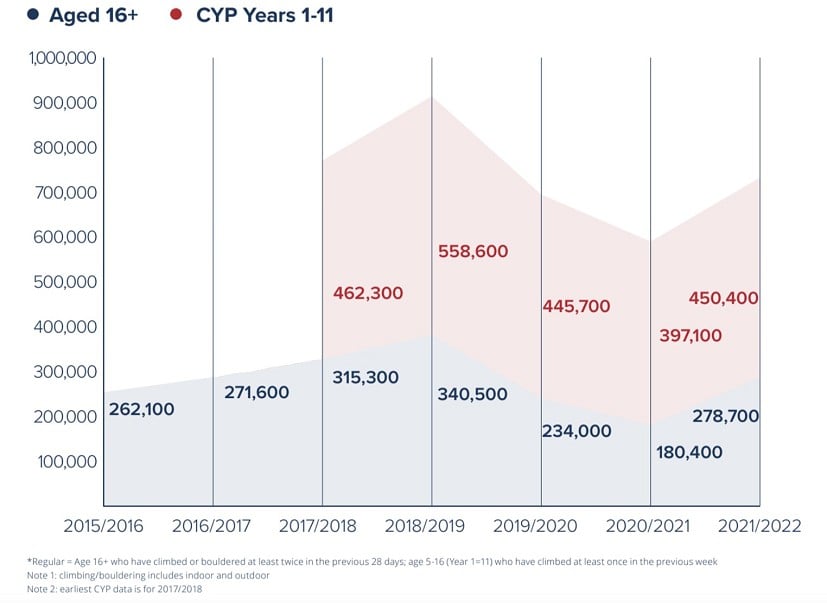

Number of 'regular' climbers in the UK by year. Active Lives Data graphed by ABC, edited by the author.

As you know, climbing has come to the masses. An estimated 729,100* of us were regulars last year. 2018, year of Free Solo, saw our numbers peak, before COVID took a big bite out of the graph, but today - if climbers had a city all to ourselves – we'd still be Britain's 8th largest. The rise in indoor gyms is of course facilitating this: there are now over 200 commercial climbing walls in the UK, and according to brand new ABC data, 26% of these are "three years old or less"**. Most gyms aren't nestled beneath premium mountainside, but are in the densely populated urban areas where over 80% of Britons live; the market is tapping our need for movement.

In a city that never sleeps, climbing soon had me so routinely exhausted that it fixed my atrocious sleep schedule. It provided a reason to take an interest in what I was eating and drinking. I made friends from all over the city, which had previously felt like a lonely place for busy workaholics. Considering how climbing can help people, it's worth saying that these wonderful benefits shouldn't be reserved for those lucky enough to have free time and disposable income: we could be doing a lot more to engage the people who might benefit most.

Once inside, the British climbing community was extremely welcoming, and soon began to encourage me to venture beyond the mats. The places to go, Shoreditch Park and Mabley Green, had London's only granite boulders because, back in 2008, artist John Frankland realised that a large bank would happily give him £100,000 to move them from Cornwall if the money got their name in the papers. And so, in the middle of Britain's great financial metropolis, I started putting off paid work to regularly play on an 85 tonne boulder near the swing set. This is how my life began becoming strange to me.

It became fulfilling simply to be a body, making meaning through the refinement and practice of movement – as if I were improving a dance that never really stopped. And though I failed a lot, was in pain a lot; it was OK. When I first hitched a ride with a complete stranger to find the Southern Sandstone outcrops, I realised I could do this forever. I gave up my desk job and started instructing beginners at Westway Climbing. Very little on my CV seemed to matter there; I realised it didn't even matter to me.

Although learning all this so late, while Alex Honnold was probably breathing through some apotheosis of a crux move, occasionally left me with a feeling of great and unresolvable waste. As if the twenty-two years walking at ground level had ruined my chances to do what I loved most in a way that others found extraordinary or impressive.

Still, I converted my own van and drove for months with my girlfriend from climbing destination to destination, and although we weren't Moffat and Moon beating the French on home turf, it felt like we were onto The Real Thing. Until of course, it was over. My stories of summiting in the Dolomites or getting pinned to a cliff after stumbling clueless into a Croatian hunt, suddenly sounded a lot like a long holiday from reality.

As a late, rather average bloomer, I'd never get sponsorships to do this stuff, and the world can rejoice that we never considered YouTube stardom. So, to build our lives close to climbing, we moved to the Peak District. The routes here trace centuries of human effort in stone, at least back to 1885, and many of them have been the hardest in the world in their day. People remember the names carved in out-of-print guidebooks for who was first, or which tiny crimps have been worn down into the gravel of time. Occasionally I'm still surprised that all of this didn't put me off. I am so small against the Peak, and won't ever scale so many of its heights.

"I'm sorry about this, you can't climb here". This was perplexing. We were hunched under the limestone roof at Lee's Bottom in Deep Dale, and an embarrassed but unflinching man was staring at us. Living down the road, I'd started to think I knew the spot. Jon Fullwood had developed the crag, Ned Feehally had added lines here, we weren't bothering livestock or damaging fencing, the site was on CROW land: what was the problem? Well, thankfully, I also knew that it didn't really matter. The best response was to leave politely. The manager represented a conservation charity tracking the health of rare plants and bryophytes. When I contacted the BMC representatives about the event, they promptly promised to advocate on climbing's behalf, and even knew what bryophytes were. They had records of previous contact with this owner from over twenty years ago, and were relieved I hadn't kicked off. I'd known just enough that I didn't spoil things for everyone. But how would I have handled this years ago when I first pitched up out of the blue?

When you are new to climbing, it's not just your own toes you might be stepping on. I can still get annoyed by the sweaty heat of an overcrowded gym, even when I'm a part of the huge populist surge myself. Outdoors, when newcomers interrupt your peace in nature, blasting their terrible music from a speaker while peeing into a bush, hell really can feel like other people. But there's more at stake than a session being ruined. Rock can be permanently damaged by being climbed wet or with improper protection. Human faeces or behaviour can make a landlord ban access to their land for decades. Even well-meaning outdoorspeople can kill endangered plants, disturb birds in breeding season, or make life a misery for locals by being the hundredth day-tripper that month to park in their driveway. Newcomers have a particular duty to educate themselves, now more than ever. But we also have a lot to give; and if pointed in the right direction, can become fellow custodians of the places we all love.

Seeing kids at the crag who look like they were born with their cams already racked, I am often reminded of my first bouldering session indoors. Eleven-year-olds have waved me through beta on my hardest sends, and told me about mysterious phenomena like 'the squeak', where you rub your shoe rubber with spit to bring it into the best sticky condition for polished limestone. They've grown up here with heroes of the sport not just on the wall, but having a gym session right across the room. I've got a lifetime of things to learn to do what they do. But that's really exciting. And it's wonderful that so many adults share stories like mine, of having their lives transformed. Because climbing doesn't care where I'm from. It doesn't care if I'm the best. It lets me be here in the right-now, until the moss grows over all my brushed foot placements. And if climbing can find me - it can find anybody.

* As per Sport England's Active Lives dataset, graphed above by designers from the ABC (Association of British Climbing Walls), edited for clarity

**2023 Association of British Climbing Walls unpublished Market Research

Comments

Excellent article. The bit about suddenly paying attention to eating/drinking because of ‘a body’ having a purpose is a great one.

That's about the most perfect article I've ever read on UKC. The excitement and enthusiasm is palpable, as is the respect for both history, the environment and the place each and every one of us occupies within the complex but fascinating game we all call climbing.

Bravo, Jonny

Such a lovely and poignant article. Reflects a lot of my feelings from moving here. It’s never too late to have idols though 😉

The best article I've read on here in ages.

A beautiful and engaging piece of writing, thank you for sharing. As someone who grew up in Cambridge and fell into climbing's lap around the age of 16 I can relate to a lot of this!