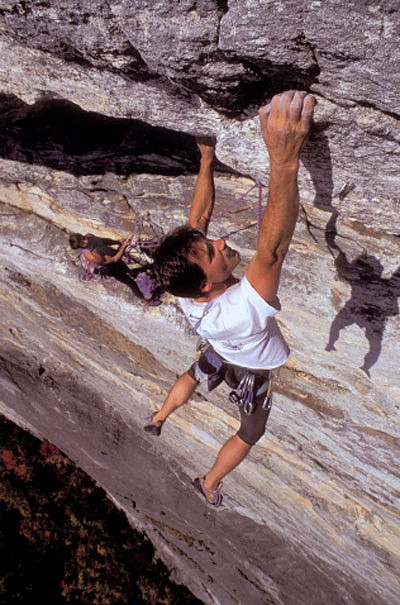

Up until the mid 1980s the Headwall section (left side) of Whitesides Mountain in North Carolina (NC) was considered impossible. How could a 700 foot wall become labeled impossible when other seemingly more impossible walls were being climbed all over the world? When we think of Great Trango Tower (20,500 feet) with almost 7000 feet of vertical rock, a scant 700 foot wall seems insignificant. Well, not so fast. The Headwall of Whitesides remained unclimbed until 1985 partially due to the staunch NC ethic of minimal bolting. Anyone could drill a line of bolts and climb the wall; this was not how locals rose to climbing challenges in NC. The other reason why the Headwall remained unclimbed was due to the label locals attached to it: impossible. Let's investigate how our expectations can create labels such as this and how these labels affect performance.

Whitesides Mountain is metamorphosed granite (Gneiss) which doesn't have the typical Yosemite crack systems. The right side leans in gently with occasional vertical sections and protection is difficult to find. New route pioneers ran it out on the easier sections finding some natural pro and drilled occasional bolts when the climbing became difficult, no natural pro could be found, or it was too runout. Several routes were done on the right side and very soon Whitesides gained a reputation for “death routes.” These routes emblazoned an image in the minds of local new-route pioneers of what climbing on all of Whitesides would be like. If climbing the routes on the right side were this serious, how serious would the Headwall (left side) be, since it is much steeper and even overhanging? This was answered with one word: impossible. This label was attached to the Headwall without serious efforts to check it out.

How or why does this happen and how or why did it eventually get climbed? Our expectations are the answer. There are two types of expectations: end-result and process. End-result driven expectation is the type of expectation most people have. It focuses our attention on the outcome, and we tend to judge whether or not we can take on the task based on our ability to achieve that outcome. In focusing our attention on the outcome an end-result driven expectation deems something possible or impossible. It's an all-or-nothing proposition. Viewing an unclimbed wall this way forces us to look through the eyes of past experience—those routes that were already put up on the right side, for instance. The steepness of the Headwall naturally caused climbers to deem it impossible because the difficulty was seen as well beyond the already challenging routes being climbed on the right side. But this “well beyond” thought originated from their perception which was created from past experience. In essence, the wall was labeled “impossible” because the end-result was seen as unattainable.

A process driven expectation, however, focuses attention on what one can do now, in the moment. It is always possible to engage a route. We may not get far but we'll at least be engaging the experience. And that experience occurs foot by foot and moment by moment as we climb up the wall. Viewing an unclimbed wall this way allows us to look through the eyes of possibility. We will use past experience as a base of knowledge to build upon, not as a limit to what can be accomplished. The Headwall is steep but that didn't mean it would be poorly protected as the routes on the right side were. Expecting that an ascent could be possible allows one to engage it one step at a time. Once engaged, the present experience determines whether or not the wall can be climbed, not past experience.

The team that did the first ascent of the Headwall hadn't put up any new routes on the right side. Therefore they didn't have past “Whitesides” experiences to cause them to buy into the “impossibility” label. This made it easier for them to focus on the process. They looked for ways to engage the challenge. In other words, they used present experience to look for things they could do that would help them understand whether or not it was possible. Initially they rappelled the cliff (a typical activity by local cavers) to get a closer look at the features. From that experience they learned they would need to aid-climb on hooks, free climb between pro sometimes for long distances, and drill an occasional bolt. They also learned that falls would be clean due to the steep, overhanging nature of the wall. Ironically, the overhanging nature of the wall, which was a key characteristic behind labeling it impossible, actually assisted in making it possible. Taking long falls was a risk they were willing to take. They engaged one step at a time and each step showed the way for the next. After three days, they stood on top.

By expecting it was possible to climb the Headwall they freed their attention to focus in the moment on how to engage the challenge, which was all it took to show them the way. Expect that it is possible to do a climb, not that you will!

Arno Ilgner is founder and president of Desiderata Institute, a multi-faceted medium which includes the Warrior's Way Course — designed to specifically help climbers overcome mental obstacles that are inhibiting their performance. Since 1973 Arno has developed and perfected specific physical and mental training methods, which are not only unique but highly effective as well. These methods are taught in the Warrior's Way Course. Through the Institute he also guides clients on mountains and cliffs in the Southeast USA. He served as a platoon leader in the US Army with tours of duty in Korea and Colorado has been a member of the American Alpine Club since 1983. He co-authored the first guide book to Fremont Canyon in Wyoming, and has published articles in Rock & Ice, Boulderdash! and Climbing magazines. Arno's interests range from mountaineering, to sport climbing, long free traditional routes, to big wall climbing.

His book The Rock Warrior's Way: Mental Training for Climbers is available from his websiteThe Warrior's Way and from Amazon

Comments