One school of thought has it that the Harpur Hill affair was just a bunch of old beardies banging on about some dodgy doings in a manky quarry. Personally, I think it was the most significant test case to date of the acceptability of mass bolting in the UK. It was never just about Harpur Hill. There was a real fear that, if bolting at Harpur was deemed acceptable, many traditional crags, such as Staden and Stoney would promptly go under the drill. For instance, at about the same time, an official request was made for lower-offs on the quarried grit of Yarncliffe, just a few miles away from Stanage. So people who scoff, “Bolts on grit? It could never happen!” need to take a good look at history. It nearly did happen. Bolts on Cloggy? That's happened - before most people on these forums were born. Towards the end of the article I suggest that “those who take their history for granted tend to lose it very quickly indeed.”

It's hard to convey the sense of paranoia engendered by Harpur Hill. It was climbing's Dunkirk. The 'gutless bolters' (not Sid or Bill particularly, but others, supposedly waiting in the wings) were going to sweep aside 100 years of cherished tradition. Of course, as we now know, this didn't happen. But it might have.

The first couple of magazine writers, in effect, dismissed Harpur as, “Manky quarry –so what??” To their great credit (and with Ken Wilson bellowing in their earholes), Geoff Birtles and Ian Smith, at High,took the opposing view that the very future of British climbing was at stake. Now Geoff, in particular, was a long-standing mate of all the chief protagonists – 'Big Sid' Siddiqui and Bill Birch, versus 'End of the World' Wilson – and didn't want to fall out with any of them. Neither, I suspect, did he want to risk getting such a vital issue wrong. So, wishing to avoid a messy mixture of bad blood and egg on his face (ugh!), he cast around for disposable cannon fodder and came up with me. If I cocked it up, good 'ole Geoff could spread his hands wide and go straight for the sympathy vote. “I was just giving the lad a chance – well what a tosser he turned out to be!”

Now, as it happened, I'd dealt with a few slippery, fractious disputes in the mucky boiler rooms of British industry, so this rumpus was nothing new. Pretty soon however, every man and his dog were bellowing in my earholes! Sid was miffed and had a go at me in print. I threw a mad rant at Wilson (which he barely noticed!). Bill Birch, bless him, remained the soul of affability throughout. In the end, the biggest scare turned out to be Wilson's mate, Frank the Decorator, getting an eyeful of Gill Kent, comely editrice of On The Edge magazine, clad only in her winceyette nightie! (It's claimed Frank was so disturbed by this apparition of loveliness that he had to scale the Eiger in Winter to regain his senses.)

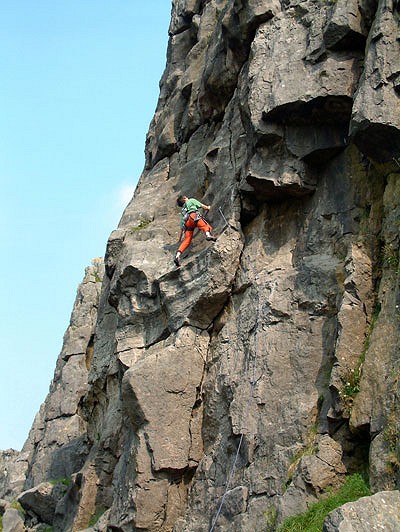

At Harpur, the bolts had gone in a tad too quickly; they certainly came out far too quickly. Prevailing opinion decided that we didn't want traditional crags bolted. Somehow the end of the world didn't happen. We voted instead for peaceful co-existence, which has continued to this day. A while later, Gary Gibson went back to Harpur, rebolted it (within accepted guidelines) and carried on to find many worthy routes of his own. In decent weather, Harpur is a great place to climb. The jugs on Coral Seas (F6a) and the crimps on Power of Sole (F7b+) are a delight - and there's loads to go at, in-between. We should be grateful to Sid, Bill and Gary for all their hard work at Harpur. (Believe me, it is hard work!) We should also be grateful to Ken and his mates for having the guts to speak out.

Twelve years later, we still have the relatively peaceful co-existence of Sport and Trad. Why don't we use the Continental term 'classical'? It's so much lovelier than 'Trad', which has a horribly naff ring to it. We also have many more people coming into climbing via indoor walls, scratching their heads and wondering why the outdoors shouldn't be sanitised. A few diehards remain, who spit on les spits and regard 'Sport climbing' as an oxymoron and a downright perversion. Meanwhile, other sanitising elements have crept into climbing. Bouldering mats tame the anklesnappers of yore. GPS devices make map reading as obsolete as crochet. Mobile phones get us straight through to the long-suffering rescue teams. Requests for beta via the internet make us all conquistadors of the useless. Well, at least none of these innovations directly damages the rock. And at least nearly everybody scorns chipping and resin, which can wreck the place in five minutes flat.

Ours is a relatively tiny island. We don't have a Matterhorn. We don't have an El Cap. We don't have a Walker Spur. But, instead, we have the most amazing diversity of climbing, together with a wonderfully rich history. So far, tolerance and peaceful co-existence have served us well. I very much hope that they will continue to do so.

Mick Ward

On The Dark Hill by Mick Ward

By now, many climbers will be aware of the controversy which has taken place this summer about the development of Harpur Hill quarry, outside Buxton, in the Peak district. The controversy, which is threatening to become somewhat of a cause celèbre, is complex and multi-faceted. The climbing history of Harpur Hill, the personalities, behaviour and motivations of the protagonists, the substantive issues and their implications and the political process and its implications all come into play. So too does personal experience.

Let's start with the place and its history to the present day. Harpur Hill is not so much a quarry as a collection of quarries, poised above Buxton. In some ways it conforms to the manky quarry image, in other ways it doesn't. There are spoil heaps, some grassed over, some not. There is the usual turquoise pool. On one side, it overlooks a rather depressing array of what appear to be council houses; on another side, there is a huge lake of aluminium roofing, covering an industrial site, from which emanate metallic voices on an unseen tannoy. Across the way is the most glorious view imaginable, of dark green wooded hills rising to heathered Pennine moors, with thin ribbons of road. Below is Buxton, with its Pavilion, home to climbers' periodic discourse. As with the Llanberis slate quarries, Harpur has ugliness and beauty. Both qualities have now been significantly enhanced by human agency.

Although the quarry appears to have been used for pegging practice in the 1950s, the first recorded climb at Harpur is Graham West's early 1960s route, The Seven Deadly Virtues. This took the classic line, a large hanging groove in the centre of the most compelling sheet of rock - the right hand side of Papacy Buttress. Although aided, on bendy pegs, it was a highly adventurous undertaking. In the mid-1960s, Bob Dearman climbed its equally classic counterpoint, The Seven Deadly Sins. Trevor Morris freed The Seven Deadly Virtues and Colin Foord made his One Deadly Variant to Virtues. Pete Townroe found the delightfully named Jam Butty Mines Crack. All of these went at about VS/HVS. Other routes, such as the appropriately named Lust, were done by various locals, such as Dearman, and casually recorded, if at all. In those days the quarry was owned by ICI, who actively discouraged climbing. Such discouragement brought this wave of development to a premature end.

Apart from odd visits, the place then languished for nearly 20 years until 18 routes were done on another buttress, the Lower Tier, in 1986, by a Glossop team featuring the legendary Peak activist, Malc Baxter. Within three months the number of recorded climbs doubled. The routes were written up in the Peak Limestone guide with the stricture that climbing was not allowed and route descriptions were merely for posterity. With what now appears to be prophetic prescience, Baxter also wrote, 'All the climbs are on excellent, steep and often rough limestone, any loose rock having been cleaned. After doing a couple of climbs without using bolts or pegs, it became a matter of pride to climb here with only natural protection, so, for the purists and upholders of tradition, here is a NO PEG and NO BOLT AREA which it is hoped will remain so.'

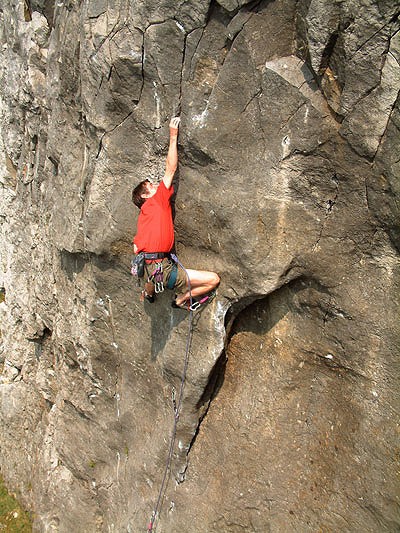

Within the last few years, the ownership of the crags changed hands and objections to entry relaxed, allowing more people to make successful visits. Two of these visitors were the well-known and highly experienced activists Nadim (Big Sid) Siddiqui and Bill Birch. In their words, “Utilising the sum of our climbing experience, carefully assessing the nature of the crag, and consulting with many climbers we know, we came to a decision that was logical and obvious. Harpur Hill would make a brilliant middle grade sport crag, with a sprinkling of harder routes.” Accordingly, after a huge amount of cleaning and other work, (removal of loose, tottering blocks, etc), they established 26 new sport routes, of all grades from 4+ (VS), to 7b+/7c (E6). The title of one such route, Buxton goes French, amply illustrates their theme. They felt that they were operating in a context whereby, “the case for peaceful coexistence of sport and traditional climbing is well established.”

Acting on information received, local climber and mountaineering publisher, Ken Wilson, visited the crag with two of his friends, Frank Connell and Tim Cumberland. Horrified at what had been perpetrated, they engaged Siddiqui and Birch in protracted debate. By his own admission, Wilson was “incandescent” with rage. Perhaps unsurprisingly, no agreement was reached.

At this point, the two accounts differ badly. Siddiqui and Birch are adamant that an undertaking was received that there would be no efforts at bolt removal without a consultation period. Wilson, Connell and Cumberland are equally adamant that no such undertaking was given. In the event, before long, many of the bolts and lower-off's had gone. Both parties have issued statements justifying their positions. Wilson, Connell and Cumberland were full of praise for the Herculean cleaning task performed by Siddiqui and Birch - as we all should be. Superb climbs have resulted. But they were unrepentant about the bolt removal. As the summer has progressed, the affair has dragged on, with the prospect of a bolt replacement/removal debacle, unsatisfactory to all.

What is the truth of the situation at Harpur Hill? Siddiqui and Birch say that, “you, the climbers will be the final arbiters,” a sentiment with which Wilson concurs. They end their statement thus, “I suggest you go to Harpur Hill yourself, weigh it up and make your own minds up. Don't be dictated to.” In this, they are undoubtedly right. I went to Harpur Hill twice, the first time with Wilson, the second time on my own. (A third visit, with Siddiqui and Birch, was frustrated by their work schedules.) My personal experience relating to the following considerations arose mainly from the second visit.

The first issue is the stability of the crag. Quarrying has stopped here fairly recently compared with other Derbyshire quarries. Siddiqui feels that large areas of rock are fundamentally unstable and that nut placements will thereby easily rip out. When he tested such placements on the upper part of Papacy Buttress, some of them did rip out. As we know (or should know), most quarries have their fair share of vertical rubble; in any case, they should be treated with a great deal of caution. Undoubtedly Harpur, like many quarries, has rock of every gradation of stability, from excellent to lethal. The stability argument seems no justification for bolts. Bolts were not used more than 25 years ago on the big routes at Langcliffe Quarry - the most dangerous rock I have ever climbed on. They were not generally used at Warton Main Quarry - reputedly nearly as bad. People like Mick Fowler and Paul Pritchard didn't resort to bolts on loose rock. And there are many other examples. In short, people have safely climbed through far worse terrain, on innumerable occasions. Harpur is not to be underestimated but, in truth, there are far greater candidates for instability. The main face of Trowbarrow has been expected to fall down for years. We're still waiting! Besides, if Harpur really is that loose, then it's probably going to collapse on you anyway.

Have bolts been placed next to nut placements? Yes. The ironically entitled classic groove of El Camino Real has perfect placements, as has the crack on the marvellously named Luddite Thought Police. They're entirely unnecessary and thereby constitute a grave affront to many climbers. With other placements, some are in otherwise serious situations; many are not.

Have holds been chipped? I think not. The authenticity of holds on the crux of Luddite Thought Police has been questioned; similar doubts have arisen about holds on routes to the left of Jam Butty Mines Crack. After inspecting all of the aforesaid holds, I am prepared to put any anomalies down to heavy cleaning, rather than deliberate chipping. Others disagree.

Have existing routes been retrobolted? The Siddiqui/Birch team emphatically say, “No!” and their opponents equally emphatically say, “Yes!” It seems to me that existing routes have indeed been retrobolted. At the bottom of the groove of Seven Deadly Virtues, you can stand with your right hand in the groove and your left hand on a bolt. If that's not retrobolting, then what is? Even where you can stray off a traditional route for a move to clip a bolt, surely you've effectively retrobolted the route? Colin Foord, who has climbed at Harpur Hill since the 1960s, has this to say about his recent ascent of his route, One Deadly Variant. “Three bolts were found to have been placed obtrusively on the line of the route and then daubed with epoxy resin in a most unsightly manner.”

What about lower-offs? Alternative belays, such as stakes, are eminently feasible for those routes which finish at the top of the crag; for those routes which don't, alternative belays may well be found. But, of course, if you develop a cliff as a sport climbing venue, then the provision of lower-offs is part of doing a good professional job. Anticipating heavy traffic at Harpur Hill, Siddiqui and Birch were against lower-offs shared by different routes; consequently the number and proximity of lower-offs have been deemed highly offensive by their opponents.

What about the aesthetic effect? Well that depends upon your aesthetics. Many people find fixed gear, particularly lower-offs, unsightly; others don't mind, or value the functionality, or cite the erosion of cliff tops and descent gullies. The imposition of technology upon specific features of rock architecture can have an added poignancy. Wilson pointed to a magnificent elephant's ear, which might have been sculpted by Henry Moore, a classic last great problem, with negligible nut protection. It was (still) adorned with two bolts which facilitate, “two brilliant routes on excellent (!) rock” [Cairn and Stealth. Siddiqui/Birch quote, exclamation mark mine.] Wilson felt that the bolts were, “like whiteheads on the face of Marilyn Monroe...”

Perhaps inevitably, the motivations of the protagonists have been called into question. Siddiqui and Birch speculate that Wilson stands to gain commercially from the attendant publicity, whereas he feels that it's as, if not more, likely to result in commercial loss. Certainly their motivations appear to be incredibly altruistic in spending considerable time and several hundred pounds establishing bolt protection for many routes which they could run up without bolts. Either that is the case or there are hidden agendas, the most obvious of which is the one they have levelled at Wilson: commercial gain. Both Siddiqui and Birch treat questions about the owner of Harpur Hill with a firm, “no comment.” If there has been some secret deal struck with the owner of Harpur Hill, who is understood to be seeking planning permission for a sports centre featuring climbing, then Siddiqui and Birch stand to gain the scorn of many of their fellow climbers. Obviously one hopes that this is not the case. As with any of us, they must be considered entirely innocent of duplicity, lacking proof of guilt. This is only fair.

The Wilson, Connell, Cumberland statement suggested that there may be legal risks for those placing large amounts of fixed gear - particularly lower-offs. This may have been designed to warn off possible corporate sponsors behind Siddiqui and Birch. However, arguments for corporate legal responsibility can become arguments for individual legal responsibility. What self-respecting climber would have dared to sue Tom Proctor if the old red in situ sling on Our Father had failed? Legal arguments may bring a plague down on all our houses.

Is it simply a question of personalities? Almost certainly it is not. Wilson's fervent commitment to ethical standards in climbing sometimes comes across as a kind of loony moral fundamentalism. As it happens, he is not against bolts, per se, at Harpur Hill; he is, however, against a blanket sport climbing approach, rather than the odd bolt in the odd very hard route which, “might have been acceptable,” in this case. At a meeting of the BMC area committee, swollen to some 35 people by this debate, most took a far more stern line than Wilson, Connell and Cumberland. Siddiqui and Birch, for their part, claim overwhelming grassroots support for their actions. Sad to say, at the aforesaid meeting, not one person was prepared to argue their case. Be that as it may, there may now be a significant number of people who would quite like to have bolts in certain hitherto traditional areas.

What do the erstwhile developers of Harpur Hill think? Bob Dearman says that he is “violently opposed” to the bolts. Malc Baxter says that, “I'm with Ken [Wilson] 100%. I detest the bolts. If you can't climb a route without bolts, you should leave it alone.” Colin Foord notes that, “and so the bolts were removed - a course of action which has my full approval.” He goes on to state, “obviously the rock climbing world must send a clear message to those who have drilled their way across this piece of Derbyshire Limestone - overriding and disregarding previous achievements - that theirs' is not the way forward but is, in its most charitable light, a misguided enterprise of fearsome proportions. The BMC, in its monitoring and guiding role, must be firm and decisive in its response as a matter of urgency.”

The relevant public forum was the BMC area committee meeting held at the Cavendish Arms in Pilsley on Friday, September 9th, 1994. Here, after lengthy debate, it was agreed that the bolts should be removed; within two days, nearly all were. So far, about 150 drilled points have gone. Siddiqui feels strongly that the aforesaid meeting and its aftermath constitute a travesty of justice. He claims many climbers simply didn't realise that the future of Harpur Hill would be determined at this forum and, consequently, a judgement has been got in, “through the back door.”

Readers in Auchtermuchty and Dingle will doubtless be amazed by all the fuss about Harpur Hill. Who cares what happens to a manky quarry? Well, as mentioned earlier, it's debatable whether Harpur is merely a manky quarry. Even if it were, Millstone was once a manky quarry and the wings of Dinas Mot were formerly dank and dirty. Goat Crag was once buried deep under vegetation... History teaches us that facile first impressions are often later proved wrong. Harpur Hill is almost certainly a significant addition to Peak climbing.

Undoubtedly Harpur Hill is also being viewed as an inevitable test case. Some other quarries, such as Castle Inn Quarry, (retrobolted twice), and Parrock have recently received the sport climbing treatment. But Harpur Hill is viewed as the Maginot Line of bolting for the masses. It is feared that, if this falls, many other Derbyshire crags are right in the firing line. Siddiqui and Birch would almost certainly be horrified if Staden were bolted. But crass commercialism and pseudo-educationism would probably love nothing more than the sanitising of climbing.

For - and make no mistake - this debate is really about the sanitising of climbing, not just bolts. Bolts are merely a technology of such sanitising. Bolts initially served the same purpose as pegs for earlier generations; they provided a means for the elite to 'improve'. As with pegs, (and chalk), they were quickly seized upon by the masses. Continental routes have been butchered, then and now. Then, traditional British ethics prevailed; but what do we do now?

Should there be easy bolt routes for the masses? Some people would claim that not having them constitutes flagrant elitism. The terrible truth is that the greatest argument for elitism is probably the rock itself. Climbing, as Siddiqui and Birch fully acknowledge, is inherently dangerous. Flinstone's Wall, at Harpur Hill, is, “home of three of the easiest sport routes in the Peak,” VS all, (two at 4b). With well-cleaned yet still slightly friable rock, if you really need the bolts on Flinstone's Wall, it's probably dangerous for you to climb there under any circumstances. Conversely, if it's not dangerous for you to climb there, then you certainly don't need those bolts. To bypass a climbing apprenticeship is to court ultimate disaster; the rock will not forgive human error.

A compelling objection to the sanitising of climbing is that it denies us the primacy of experience. If you get up a hard bolt route, you'll almost certainly remember the grade. You may also briefly remember the crux moves, at least until the pain in your fingers fades. But the route, the big lead? It wasn't a big lead. It was a redpoint. There's really not that much to remember. With easier routes, there's virtually nothing to remember. I've done hundreds of easy bolt routes. While I've enjoyed most of them, I can't remember any of them. They were convenience climbing, fast food, ten minute efforts, no more. By contrast, the experience of many traditional routes, even easy classics, will remain with me to my dying day. This is so for all traditional climbers; irrespective of grade, we play the game of games together. In our fumbling struggles are faint echoes of the strivings of those who have done Indian Face. What did Dawes, Dixon and Gresham feel as they teetered past the crux, giving it all they had and more? Each could have placed a bolt by his waist.

I think that we need to consider the world which we are creating. Convenience climbing is merely another facet of convenience living. Bolt ladders mean that routes become the same the world over. You must have noticed the anonymity of continental bolt ladders; you don't know who did them, nor do I. There's no history, no tradition, no culture; we just don't care. This is probably part of a much greater process of cultural meltdown, aided and abetted by mass technology, by which everywhere is rapidly getting like everywhere else. Is this really what we want? Will our children's children thank us for a world which is bland, homogenised virtual reality? I doubt it. Climbing is a primeval expression of the act of living. This is its extraordinary power. Let's not lose it.

Let's also not take our history for granted, for those who take their history for granted tend to lose it very quickly indeed. We may think that bolts on Stanage and Cloggy are unimaginable, that we know where to draw the line. But we've had pegs on Stanage and bolts on Cloggy and only determined action got rid of them. What would we do if we found Carreg Hyll-Drem today? Not in the mountains, manky, steep, friable rock, hard to protect... Let's face it - some people would bolt it senseless. That's not what Brown did; is it what we should do?

We must create clear guidelines to avoid sliding into an ethical debacle. We have to determine what types of climbing we want in Britain. We need to consider what we will bequeath to future generations. These are not decisions to be marred by moral laziness or short-termism. They are not to be taken likely.

We probably need an ethic. Here's one. Bolts were originally placed to make the supposedly impossible possible. Malc Baxter's view, agonizing in its soul searching, is that, where a person can climb a British route without its bolts, that person should be conceded the right to remove those bolts. Climbers would then, in the most direct manner possible, become the legitimate moral guardians of climbing. This would be a principle in accordance with our deepest traditions. Would Menlove Edwards, who dispensed with the pegs on Munich Climb on Tryfan in 1936, not turn to us and give a wry, austere smile of approval? I think he might.

Comments