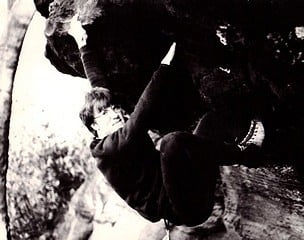

Both he and I know that that the carefully placed protection laced into the ledges between me and the ground will rip out the moment any weight is placed on them. Especially my weight, for even at the age of 17, I'm 13.5 stone, more suited for the front row in a game of rugby than this vertical ballet. (“With them legs Dave,” a thinner climber had once remarked, “you could kick a whale to death.”) As my calves start to shiver uncontrollably and my forearms begin to ache, I make an irreversible decision. I jump for the hold.

At this point I usually wake up with a start, clawing my sleeping wife or the pillow as I then grasped the gritty protrusions of Cratcliffe Tor, that beetling lump of rock that rises out of the inhospitable Derbyshire moorland. I am reassured to find myself horizontal and safe in bed in southwest London rather than two-thirds of the way up an extremely severe climb in the Peak District. (It was Boot Hill – now rated a gentle E3 5c. At the time, all I knew was that it was desperate.) I reassure my startled wife that it was a bad dream, before sinking into rock-climbing reveries.

Three decades on, I am one of those people who cannot see a picture rail without wanting to reach up and grab it. Or a skirting board, without feeling compelled to try it out with the tip of my toes. I cannot look at buildings, without plotting the best way to the top. As a result, I have executed brave new routes up medieval churches, the Lloyd's of London building , Nelson's Column, not to mention the precipitous south face of our home in suburban Wimbledon. All without leaving the ground.

In short, I am an armchair alpinist who, as middle age overwhelms him, retains a fascination with cliffs and crags and north faces. I live in as far from proper mountains as you can be in this country, with only the crumbling sandstone of Harrisons' Rocks within a couple of hours drive. Climbing, for me, is a world of adventure that has been preserved in the amber of memory. The glossy photos of lissom-limbed athletes dangling from improbable extrusions in today's magazines and websites act on my imagination, stirring up a tumescence of recollections.

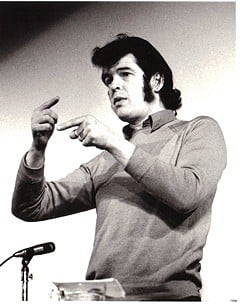

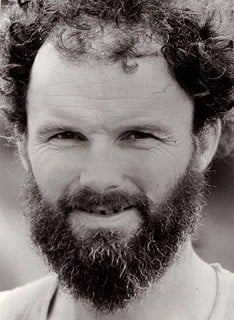

It all started in Nick Estcourt Outdoor Sports, a shop in Altrincham named after the mountaineer who was killed in an avalanche on K2. I only met him once or twice and I recall a dark expanse of beard and little else. He was a shy man, at home less in the chi-chi suburbs of South Manchester than on a north face in the Hindu Kush. His mates comprised the so-called Altrincham All-Stars, a band of climbing legends including Chris Bonington (who had moved away before I took up climbing), Martin Boysen, Dave Potts, Dave Pearce and even Ken Wilson, whose climbing never the heights attained by the others but who was a Boswell to their collective Dr Johnson. Ken talked about climbing, loudly and enthusiastically, and he wrote about it and produced the books (Hard Rock in particular) in which his friends' exploits were mythologized.

My job was to sell expensive ski-wear to suburban housewives, and bits and pieces of climbing equipment to impoverished rock-climbers who could only afford to buy one karabiner or chock or runner sling at a time. They would accumulate a full rack of gear over a period of months. I was just there on Saturdays, hence my nickname “Saturday Dave” to distinguish me from Dave Pearce, who ran the shop, and Dave Cooke, who worked in London as an agitator for the Communist party but was Ken's childhood friend and was an honorary All-Star. (Of the three Daves, it's really sad to think that I'm the only of the three Daves to be still alive: Dave Pearce died in an accident on Gogarth and Dave Cooke was killed en route to Australia on his bicycle.) Rab Carrington worked in the shop for a while, as did Willie Todd, who dragged me up many a route in those days.

When not eavesdropping on the conversations of these climbing greats, I would chat with the younger climbers about the audacious routes they had tried the previous weekend. The conversations all had a similar pattern:

“I did the Dangler last week!”

“Wow, what was it like?”

“Pretty hard, but not as hard as the Tippler.”

“I've done the Tippler and it wasn't really 5c ... so is the Dangler only 5b?”

“Strenuous 5b.”

“Thuggish if Joe Brown is to be believed.”

“Well you have to do a few pull ups and it's awkward getting in that bit of gear”

“What about the famous heel-hook?”

“Undoubtedly the crux...it was like this”.

I was too heavy to be any good but for a while it was all-absorbing. I was a fanatic – hitch-hiking out to Stoney Middleton for the weekend, kipping out in the woodshed or Windy Ledge. Sometimes I went further afield at the weekend, to North Wales or even Scotland. My high point in terms of grades was probably the lasso pitch of White Slab on Cloggy (E something very high the way I climbed it, 6a), which I led without the lasso or protection of any kind, and I was proud to complete Cenotaph Corner and Sloth.

One time, I hitchhiked bag from Wales just after slipping in a pile of sheep sh*t outside my Llanberis bivvy. I was unfortunate enough to be picked up by one of my all-time heroes – it was Martin Boysen being driven in Dave Potts's Audi – and so it was excruciatingly embarrassing when these legendary figures started sniffing the air, soon after I got into the car, questioning where the obnoxious smell came from. (Either they were simply too nice to blame it on me, or they got used it: they didn't throw me out and gave a lift all the way home.)

Then there were sweaty sessions in the improbably confined space of the shop cellar, where Dave Pearce and others constructed a minuscule climbing wall with some desperate problems on the underside of the stairs. And the fabled Tuesday evening outings when the All Stars would convene from all parts of the UK and drive up to the Peak in search of obscure crags and strong beer. There were memorable, sun-drenched evenings on Ramshaw or Bowderstones, and hopeless attempts to get up the first ten feet of Mortlock's Arete at Chee Tor or Beatnik at Helsby. More successfully, I got to the top of some strenuous E1 on Wildcat Tor, seconded by Ken Wilson, who couldn't make an orthodox ascent because he had left his EB's behind and had to climb in his suede boots. As he hauled himself up the rope to the belay, he congratulated me on being a proper climber at last.

I relished all sorts of things about climbing – the particular thrill that came with slotting my hand into the perfect jamming crack or the elation that came with hauling myself through an overhang to reach the top. But I wasn't a proper climber after all. I moved down south and went to University and fell in love a few times and the commitment ebbed away.

I haven't climbed for ages now, but not so deep down, I remain a climber, and one day I am going to pack up my rucksack, sling on a rope, and head for the crags, in search of that distant country which long ago stopped issuing visas to middle-aged men: my youth.

Comments