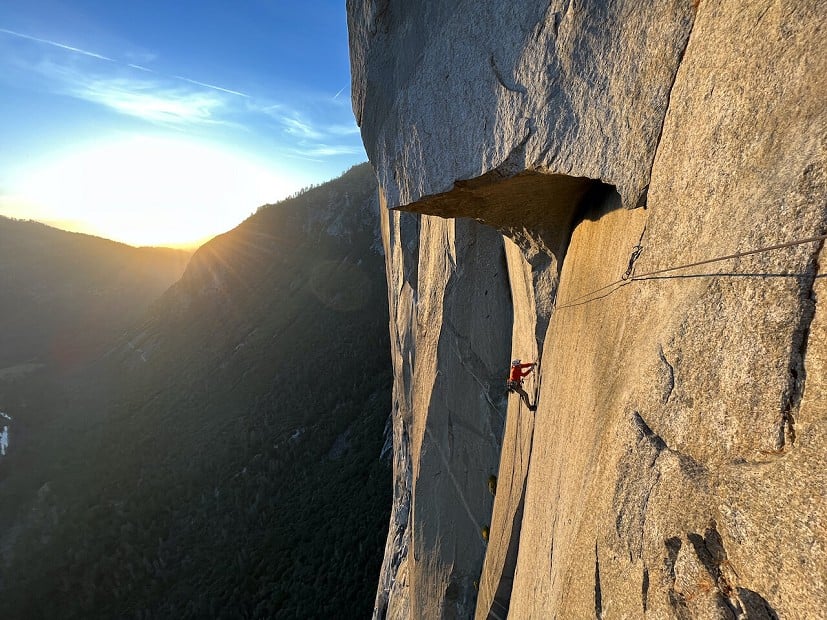

Tom Ripley shares some nuggets of wisdom from his experiences of attempting and finally climbing the Nose of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park.

The Nose of El Capitan is one of the most famous climbs in the world. Like the North Wall of the Eiger, its individual pitch names are part of the climbers' lexicon. If phrases like Great Roof, Changing Corners, Stovelegs and King Swing mean nothing to you, it is worth searching for a topo or watching a video of the route on YouTube.

Last month I climbed the Nose of El Cap with John Roberts, hauling myself to the summit tree at the end of our trip, with one just day remaining before our flights home. Like many climbers, I'd failed on the Nose (three times) before I actually climbed it. Here are some insights to help you avoid the same fate.

Learn the basics in advance. Easy aid, jumaring, lower-outs and hauling should all be practised in advance by all members of the team at your local crag or climbing wall (ask permission beforehand at the wall, though). Chris McNamara's book How to Big Wall Climb is both clear and concise.

Free climb as much as you can. You'll go a lot quicker if you can free/French free lots of sections, particularly lower down, but don't get stressed about it if you end up pulling on cams on 5.8 cracks. A Fifi hook is very useful. The Stove Leg Cracks are 5.8, but do not expect this to bear any resemblance to VS.

Take four ropes. For reasons best known to themselves, the National Park Service is happy to have permanent fixed ropes going down from the Heart Ledges (on Salathe Wall/Freerider) and East Ledges (the normal descent route from El Cap), but aren't happy for there to be perma-fixed ropes down from Sickle Ledge on the Nose. This is a bit annoying for visiting Europeans with tight luggage allowances. It's a good idea to bring four 60m ropes with you as this will allow you to fix to Sickle Ledge and the pitch above (pitch 6 on the topo). Then you can start early and not rely on a lottery of whether other climbers have fixed ropes or not. On your ascent, you can carefully lower two ropes to the ground to be collected after your ascent. I'd take a couple of old ropes for this purpose, as you'll be less sad in the unlikely event they get pinched before you get some friends to collect them.

For your main lead line, bring a chunky 60m rope (10-10.5mm). Sharp edges are scary, particularly the ones in the Changing Corners, and especially when swinging around on jumars with a kilometre of air beneath you. For hauling bring a light 65m static rope (9-9.5mm) as they're more efficient to haul on. A short (20m) lower-out line is also necessary. This can be a section of old half/twin rope.

Take duplicates. On trips like this it is worth having two of a few crucial things (sleeping bag, sleeping mat, glasses, toothbrush etc.) so you can leave one set on the wall and use the other in camp. This way you don't have to pack up in a mad rush in the middle of the night, and inevitably forget something.

Go light. Hauling a light bag is much less exhausting than hauling a heavy one. If you're a party of two and you're space-hauling after day one, you've got too much junk. That said, being caught in a storm on El Cap would be unbelievably dangerous/scary. Make sure everyone has the following: full waterproofs (good ones), a big synthetic belay jacket, a synthetic sleeping bag, bivi bag, a bothy bag or portaledge fly (better). You don't want to end up as a case study in Accidents in North American Climbing.

Don't skimp on water (and make sure you drink it). Apparently a (US) gallon (3.78 litres) per person a day is the typical amount of water consumed while climbing El Cap. It was pretty hot this October (5 degrees hotter than average) so we opted for a gallon each per day, plus an extra gallon between us per bivi, and two small bottles of Coke (totally worth it) for the descent. We pre-added electrolyte tablets to our general drinking day water in advance, as you definitely won't have time to do that once on the wall. Taking extra water allows some margin for error if you get caught in traffic, or are slower than you planned. Also, don't count on finding extra water. Lots of write-ups talk about the Nose being littered with abandoned water from bailing parties. While this might be the case, I really wouldn't count on it. We only encountered one lonely bottle at Dolt Tower.

Get up early. In my view, the key to success on the Nose is not getting caught behind others in the cluster between Sickle Ledge and the Stovelegs. On our first attempt we climbed and hauled from the ground to Sickle in five hours. We then spent five hours sat on Sickle Ledge watching a very slow team go nowhere, and then bail. The best way to mitigate this is to get up very early, having pre-hauled to Sickle Ledge, and fixed the pitch above, a day or two before. We started the pendulum pitch to the Stove Legs in the dark, but we were the first team that day.

Don't be afraid of the dark. With a good head torch aiding in darkness is just the same as in daylight, only less exposed! If darkness falls before you get to your bivi ledge suck it up, expect everything to take 50% longer, and keep on trucking to the next ledge/summit.

Don't get ill. If you're on a short trip, you have little margin for error in your schedule. With this in mind, do everything in your power to not get ill; wash your hands, wear a mask on the plane, don't share water bottles in camp, and avoid Camp 4 if you can (it's feral). We did none of those things and wasted a week of our trip feeling rough. And don't kid yourself that you can climb El Cap with a cold because it's nice and warm up there. We tried it and ground to a halt on the second morning!

Avoid Camp 4. Although Camp 4 seems to have chilled-out since I first visited — it now has hot showers, and the Rangers seem to have changed to an educate first, taser second policy — it's still totally gross (my mate found a used condom on the floor of the shower), loud and not exactly a restful place. A better tactic, especially on a short trip, would be to stay outside the park, drive in early (leave your haul bag in the bear boxes at El Cap Bridge) and spend a long day climbing to Sickle Ledge, fixing ropes and hauling your bags up. Then drive out of the park for two full days of rest and recovery, before getting up mega early on launch day (aim to get to the bottom of your ropes at 3 a.m.).

Rack well. If you're planning on aiding most of the route, you can probably get away with a double set of cams, as long as you back-clean a lot, and are prepared to accept huge run-outs. If free/French free climbing (not that I did much of that) I imagine a triple set of cams would be preferable, but even then I would expect to be lowering off and back-cleaning once a pitch or so. It is worth paying attention to the topo, doing your research and only carrying what you need on each pitch. Everything else can be left in your haul bag.

Take big cams. The topo says only take a #5 cam if you suck at offwidths. Remember: you're a Brit and you probably suck at offwidths, especially with a big walling rack and haul line in tow.

Take nuts. You'll hear a lot of chat about being able to climb the Nose on cams alone. I'm sure this is true, but that doesn't mean you should. It's also worth remembering that just like your average Brit isn't very good at climbing cracks, your average American won't be very good at placing wires (or face climbing). I was very glad to have a couple of sets of wires (one normal, one offset) with me. I avoided aiding on them unless I absolutely had to (they get stuck if you do this) but would place them as runners (like you would when free climbing). This allowed me to back-clean my cams with only faintly ridiculous runouts.

Use Totem cams. Black Totem cams turn C2 into C1. Take two (and two Blue Totems too).

About cam hooks. These have a knack to them, as I discovered, while hanging upside down from my daisy chain. Turns out that the Great Roof really isn't the place to figure out exactly what that knack is. Thankfully they're not essential and Rock 1s and 2s seem to work equally well, and are far more predictable.

Aiding in rock shoes hurts, especially if it's hot. Swap into your trainers if you know you're going to aid the whole pitch. It is worth adding some stiff insoles to your approach shoes to add a bit of support — this is especially beneficial when jumaring. Also wear over-sized comfy rock shoes with ankle protection, not your tight limestone face-climbing shoes.

Look after your hands, as without them you won't go anywhere. Wear full-finger gloves for cleaning, fingerless gloves for aiding, and crack gloves for freeing. Scrub your hands each evening with wet wipes and moisturise them. It's worth chucking a spare pair of gloves in, as it's very easy to trash your skin if jugging bare-handed.

While it does keep you warm, the sun is not your friend. Cover up! Wear a sun hoody, sun glasses, and high factor sun cream/lip balm.

Be considerate when passing other teams. Hauling alongside and passing slower teams, unless they let you through, is near impossible. The best option is to either keep climbing into the night when they stop and bivi, or to get up before them and climb over them in their sleeping bags.

Fast (12 hours or less) Nose In A Day teams won't hold you up. They'll probably know the route inside out, will tell you what they're going to do, do it, and disappear. Slower NIAD teams (20+ hours) can be a little more problematic, as they're probably going at a similar speed to you, except they'll be more tired and sketchy. However, they will still (hopefully) be quicker than you as they won't be hauling. The best thing to do is to work with them, help them through your ropes, and get them out of your way as quickly as possible.

Route Beta

Topos and write-ups often say that the first four pitches leading to Sickle involve the trickiest aid on the route. In my experience, this wasn't the case. The Great Roof and Changing Corners are far trickier, and a million times more exposed.

The Texas Flake is a genuinely dangerous bit of climbing. Don't fall off it, it's easier on the climber's left, but you face out to climb the pitch. Leave everything at the belay except a few cams and a screwgate for the bolt. Send your best chimney sweep up it.

If your mate does the King Swing first swing, they'll probably never let you forget it! Having your rope flicked over the shin of the boot will make things easier too. If you're following you will need all of the remaining rope to lower out from the King Swing. If you try to do a 3:1 lower out on the bight you'll end up taking your own King Swing, or having to jug back up and sort things out.

Leaving your haul bag above the Lynn Hill Traverse to avoid hauling through the Grey Band is a good idea. What isn't such a good idea is flaking your haul rope into a bag and leaving it there. When it gets tangled/caught in the wind it'll cause you no end of hassle. A good solution is to stack the haul rope into a small rucksack, and for the follower to take it with them, carefully paying out as they go. This should avoid any tangles and tantrums.

The East Ledges descent is no big deal; think Striding Edge or North Ridge of Tryfan level of difficulty, plus four in-situ raps. That said, the route finding is a little bit tricky, and the ledges are exposed in places. My best advice is: don't try and onsight them in the dark with a haul bag. If you top out in the dark, then have a nice bivi on top, or if you have to get down because you'll miss your flight, walk off the long way.

Final Tips

Big walling is hard, both mentally and physically, as is dealing with the heat. If you want an easy ride go alpine climbing instead.

Play to your team's strengths. Send the best rock climber up the lower half of the route, and the best aid climber up the upper part.

Tinned fruit tastes amazing at the end of a long day, almost as good as flat ground feels after three days on the wall.

Finally: as a friend told me before I first attempted El Cap nine years ago; If you don't bail, you can't fail! On that occasion I failed to heed his advice.

- ARTICLE: 5 (V)Diffs to end all (V)Diffs 11 Jun

- PRESS RELEASE: Guided Ascent of Mount Kenya December 2024 23 Apr

- REVIEW: Mountain Equipment Vega - update of a classic 5 Apr

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Meteora, Greece - A Sport Climbing Area for Trad Climbers 4 Jan

- REVIEW: Haglofs Roc Sheer GTX Jacket 14 Nov, 2023

- REVIEW: Edelrid Salathe Lite - the best helmet is the one you'll want to wear 13 Jun, 2023

- REVIEW: North Wales Climbs Rockfax 30 May, 2023

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Mount Kenya 30 Mar, 2023

- ARTICLE: Removing Stuck Gear 3 Nov, 2022

- ARTICLE: 12 Ways to Save Cash on Outdoor Gear 8 Sep, 2022

Comments

Fantastic read, thanks for this. 🙂

Some great advice in there - especially getting the basics wired before you leave home! I served my Big Wall Apprenticeship in Hobson Moor Quarry and have enjoyed passing the experience on to future generations since. Here's a blog post from the latest installment. https://rockaroundtheworld.co.uk/2022/10/02/big-wall-apprenticeship-where-better-than-hobby/

Meanwhile, sounds like you've got the "Big Wall Bug" - what's next on your list? Cheers, Dom

Having done it this season, my biggest advice would be to do something else. I found it really busy and pretty overrated. It’s not adventurous if you’re in a queue the whole way up and there are far better walls in the valley with fewer trash filled cracks. You can’t free climb as hard as you think you can on it, which is annoying, whilst the aid climbing is entirely unchallenging (We never placed anything other than bomber cams).

It’d probably be a much better route if people stopped romanticising it and saying it’s such a good route…

To be fair to The Nose, it is a very good route but as you say, spoilt , possibly ruined, by its popularity.

To Tom, recommending walking off rather than using the east ledges, I surmise you have not done the walk off, it takes ages. We also had chest high snowdrifts to content with , early June. The east ledges must be three times as quick. Easy to find and follow.

Have a like for the rest of the article

We saw one other team on day one, who we shared El Cap Tower with. There was another team behind them who stopped at Dolt. They bailed the next day.

On day two we let the other team past, as they were moving faster than us. They bivied at Camp VI. We were also passed by two NIAD teams.

On day three we saw no one all day, other than an exhausted German couple who topped out in the middle of the night, having climbed Triple Direct in a day.

I'm only recommending walking off if it's dark and you've not done the East Ledges before. I think onsighting the East Ledges in the dark, with a Haul Bag, and in a state of post El Cap exhaustion, would be extremely slow at best.

Glad you liked the article.