Despite recent concerns that technology is 'sedating' our modern society - due to a reliance on phones and GPS signals for navigation - it's undeniably true that technological advancements have their place the realm of climbing and mountaineering, if used intelligently. The trend of using Google Earth, Bing and other maps for a variety of applications within climbing is on the up - from planning expedition routes to seeking out new, well-concealed crags with the aid of a bird's-eye perspective on the chosen terrain.

The novelty of finding your own house, 'spying' on friends and re-visiting old haunts wore off long ago, and now these virtual mapping tools have a wide appeal in the mountaineering world. Coupled with drones and overly-intelligent phones, the possibilities for exploration and development are endless.

"I've been using the internet for much longer than I've been climbing and I can't quite imagine how mountaineers of old would have planned a trip with any degree of certainty. The idea of travelling to some of these places without first being able to zoom around them in my bedroom is both exciting and terrifying!" -

Intrigued by the popularity and wanting to separate the hype from the good stuff, we got in touch with serial virtual globetrotters who were willing to tell us about their experiences of mapping tools and share some hints and tips.

In mountainous areas, what Google Earth provides is topography data (i.e. an altitude profile) collected by the space shuttle and a satellite image. When you view from an oblique angle (i.e. not looking directly downwards) you are seeing the satellite image laid over the topological data to simulate a photograph taken from that angle. Formerly comprising three licensed versions, there now exist just two versions, both of which are free to use (Download here).

"Your imagination can run wild with exploring little known mountains on Google Earth!" - Will Sim

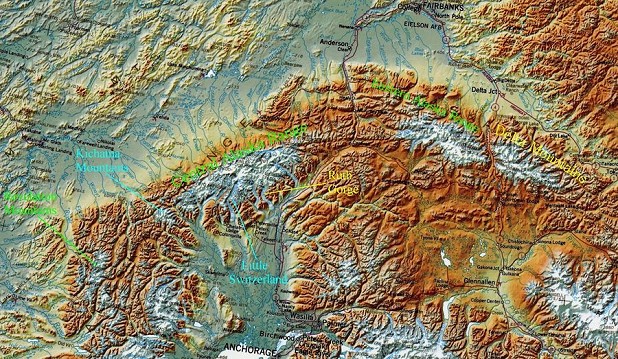

Alpinists Will Sim and Jon Griffith recently returned from an expedition to Alaska, where they climbed a new route on the NW Face of Mount Deborah (UKC News Report). In his blog, Will mentioned using Google Earth to determine the size and orientation of certain faces which piqued his interest on maps. He told UKC:

"Google Earth is certainly a great tool for exploring mountainous areas before you've been in person. With a recent trip to Alaska, I used it to find a face which from the contours on a map I knew must exist, but couldn't find any photos of. I could pretty accurately work out the size of the face, see roughly what kind of ground it was made up of, and even start to envisage a possible line and a possible descent. In the end the line I thought we might take had a serac on top of it, which is an example of something Google Earth won't always show up, but I certainly wouldn't have planned a trip around this face if I hadn't have found it there first."

In addition to discovering potential new lines, Will also emphasised the advantages of gaining an insight into the surrounding landscape:

"I also find it really useful for trying to get your head around a new mountain range; the glacial systems, how the valleys link and therefore approaches, logistics, and tactics may come in to play. It's basically a comprehensive, interactive map. There are also loads of other features on Google Earth that can be used for seeing where the sun is at certain parts of the day; what slopes are in shade and when. Another useful tool is being able to go back in time in imagery to find a shot that will show what you want to see in better definition."

Jon Griffith added to Will's experience, describing a few drawbacks of Google Earth:

"Google Earth is brilliant but I think it's just one link of the chain. Looking for new objectives in the Himalayas is tough for obvious reasons - people either keep them a secret, or no one has been there yet. I find that picking an area, then Google Image searching every peak in that area is a good start. You'll get a good idea of the geometry of that peak even if you only find a grainy image from the 1960s. From there it's about mappping that onto what Google Earth shows - but it still misses out a ton of features such as objectives dangers (seracs, cornices etc) and I dont think it's good enough to be able to pick out any definite lines."

"I guess it is cheating in a way and removes the adventure to it, but there's so much uncertainty when going to the Himalayas I dont see anything wrong with trying to stack the odds in your favour. But that's a personal choice." - Jon Griffith

Jon also recommended using older imagery from years ago as it may be of a higher quality:

"It's worth going back in time as some imagery is better in the past than the present. You can also get really geeky (worth doing) by using the images in the past to start to see major objective dangers - you can see shadow lines change as the imagery will have been taken at different times."

Comparing Google Earth to other mapping software, Jon highlighted the fact that newer technology exists which has overtaken Google:

"I don't think using Google Earth for climbing is all that new really, it's just that in recent years the imaging satellites and technology used to create mountains in 3D have gotten much better. If you look at the resolution and level of detail that FATMAP have for example, you'll see that Google Earth is still pitching way below what is possible. Drones may well be the future though - you could fly a drone over your intended objective whilst you are there to really recce out the route and spot any missed huge objective dangers. Useful for peaks that are so big you can't actually see all the lines you are hoping to climb!"

But isn't this cheating - obtaining so much information about a climb and its potential dangers from the comfort of your couch? Jon explained:

"I guess it is cheating in a way and removes the adventure to it, but there's so much uncertainty when going to the Himalayas I don't see anything wrong with trying to stack the odds in your favour. But that's a personal choice. It's hard to know where to draw the line really - a photo taken from another peak showing yours from a different angle would also be cheating in a way. Pretty much all the major routes that were climbed in Alaska back in the day were gleaned from Bradford Washburn's photos taken from the air."

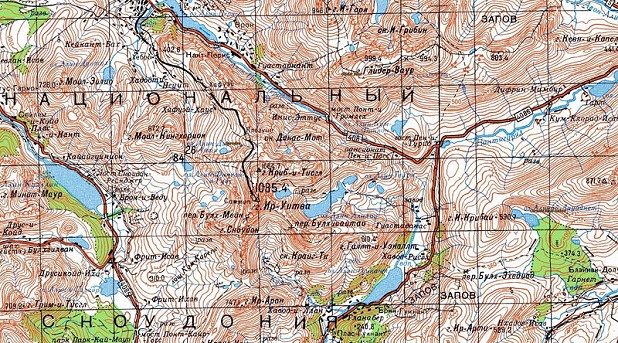

Climber and mountaineer George Cave is very much an expert in using Google Earth for expedition planning and was particularly keen to highlight the advantages of overlaying Soviet mapping onto Google Earth:

"I've used Google Earth to plan three trips to Central Asia, including one where I used the software to narrow down my destination from the whole of Tajikistan to an individual glacier. In every case, I always correlate the mapping with the Soviet military maps which are all online for free at loadmap.net. You can import these as image overlays and they will conform to the contours beneath, bringing the whole map to life. Even now after doing this for several years it still seems quite magical!"

Indeed, you can even download the entire UKC database and import that into Google Earth too, although this will soon be incorporated into the Rockfax App which will save you the bother and also enable you to carry it around with you. George went on to give some examples of where elevation data didn't quite match up in reality:

"When the elevation data is wrong, I've found it can be quite spectacularly wrong. In the Djangart region on the border of Kyrgyzstan we found a 5000m peak with a 600m face which is entirely absent from Google Earth. The summit of the region's highest peak is also completely missing, the whole top has been flattened by 300m to the height of the surrounding ridgeline. Using the Soviet mapping overlay as a check is a great way to build up confidence in an area without constantly switching back and forth between Google Earth and an image."

Thinking back to the past, George expressed his amazement that previous generations made do without today's mod-cons:

"I've been using the internet for much longer than I've been climbing and I can't quite imagine how mountaineers of old would have planned a trip with any degree of certainty. The idea of travelling to some of these places without first being able to zoom around them in my bedroom is both exciting and terrifying!"

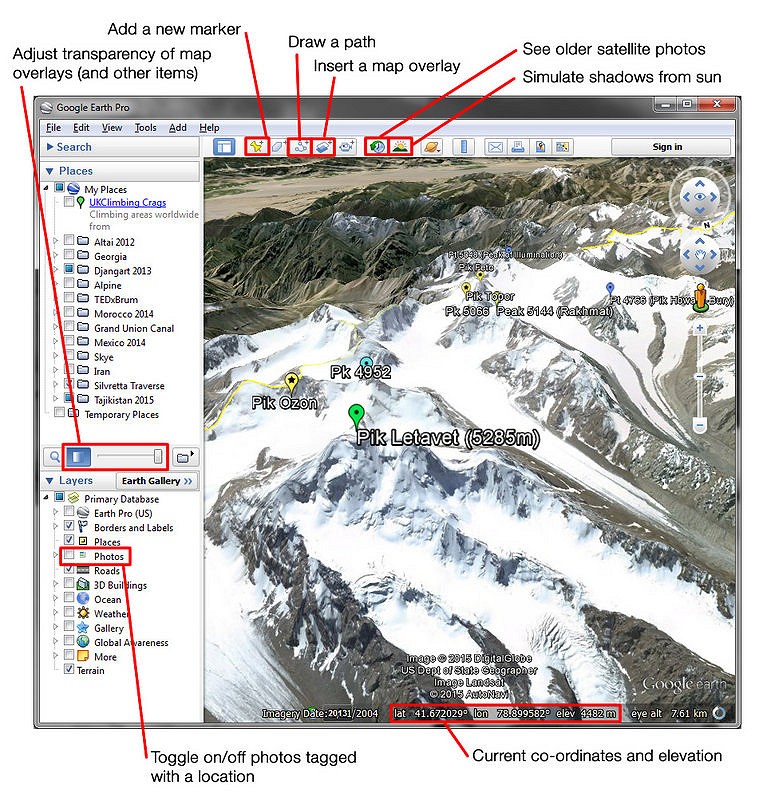

George kindly gave us the cheat-sheet below as a helpful guide to first-time Google Earth users:

Mountaineer John Proctor has also used Google Earth for expedition planning:

"I have used Google Earth in the planning of 4 climbing expeditions to the Pamir and Tien Shan). It is very useful for scoping out objectives, but be aware of exactly what you are looking at when you use it, and what its advantages and disadvantages are compared to other maps which are available."

John makes use of additional functions in the programme such as Panoramio photograph markers and the stripped-back topological map:

"If you are seeking out unclimbed objectives, the function on Google Earth and maps to indicate where photographs on Panoramio were taken is extremely useful as it allows a quick preliminary survey covering wide areas, to see which sub-ranges are well photographed and which are possibly less well-explored. You can also look at the topological data without the imagery to get a "conventional" contour map."

Regarding the advantages of Google Earth over conventional maps, John listed the following:

1. "The mapping is very up to date – you can see the date on which the satellite image was taken. So Google Earth can tell you where the snout of a glacier is now (think global warming), or where the footpaths are now.

2. When you create a placemarker, it gives you the latitude and longitude using a datum (WGS84) compatible with your GPS. You can therefore put a WGS84 datum onto maps which are lacking a modern GPS-compatible datum, as long as you don't mind doing a bit of maths.

3. The fact that you can see an (albeit simulated) image in 3D allows you to get a "feel" for the area far more easily than when looking at a 2D map.

4. The fact that it does cover virtually the entirety of the Earth's surface!"

He added:

"But there are also disadvantages. In my experience the actual surveying is not as accurate as (for instance) the British Ordnance Survey or Russian military maps. In particular, Google Earth tends to "cut off" prominent summits so the mountains are often a bit higher and a bit steeper in reality than they appear on google earth. Also, the images on Google are snapshots of what the area looked like at the instant the photo was taken. A glacier which is covered in crevasses may have these crevasses shown on a conventional map, but not on Google Earth if the image was taken during winter when the crevasses are all well-covered with snow."

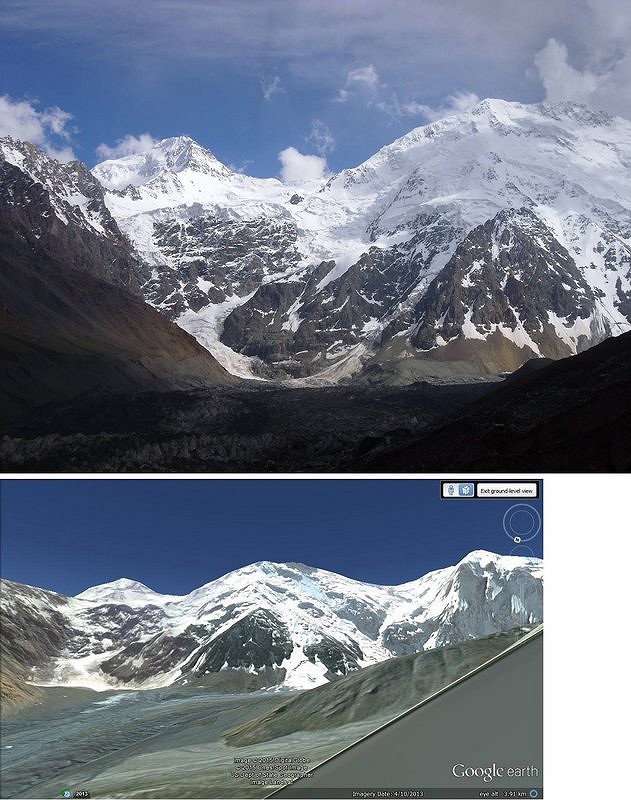

"The example above shows a Google Earth screenshot and a real photograph of some peaks slightly less than 6,000m altitude in the Pamir mountains, Tajikistan. On the left is Pik Tyndall, in the centre is Pik Agashidze and, on the right of the Google Earth screenshot but cut out of the photo is Pik Agasis. There is so much you cannot see from the Google screenshot. For starters, the right hand (west) ridge of Pik Tyndall looks like a simple snowplod on Google, but in the photograph you can see there are rocky sections which may be tricky. The imagery does show some seracs, but only the photograph shows just how bad they are.Then look at the glacier – it seems pretty flat according to Google Earth. In actual fact it is so badly crevassed it is impassable in most places."

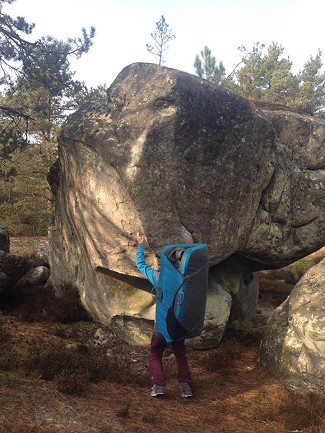

Going back to drone technology, one advocate for using drones as a means for seeking out new bouldering areas is Fontainebleau resident and filmmaker Neil Hart. Neil has been using drones to search the vast, boulder-ridden forests in Fontainebleau over the last few months, which has saved hours of traipsing through the woods looking for non-existant boulders. He explained:

"Only a year ago, we would generally have a quick look on Google Earth or on the IGN maps for new boulders here in the forest. We would target potential new boulders then set off walking. This is very inaccurate because with the bushes and trees it's very hard to spot boulders unless you are pretty much stood on top of them."

Already in possession of a drone through his filmmaking, Neil began exploring its alternative use:

"I would first target an area on Google Earth, then drive to the nearest spot I can take off from, the drones are great as I have a target range of 1km with full live HD download direct to my iPad, I can fly within 20 metres of potential boulders and also get a scale of how high the boulders are. With the drone and the technology you can simply pinpoint your GPS position and take a photo of the area. You still have to walk in and look, but it stops hours of searching through the trees.

"Call us lazy, but I call it being productive with your time and having fun, as now we are using the drones to even check out if crags are dry before walking in, as well as getting stunning aerial images when people are actually climbing."

"Here in the forest of Fontainebleau it's best to search with the drone in the winter months as there is a lot of canopy in the summer. With open areas like Africa and Spain, you can fly within a few metres of the rocks seeing if the quality is ok before you set off walking!"

"Call us lazy but I call it being productive with your time and having fun, as now we are using the drones to check out if crags are dry before walking in, as well as getting stunning aerial images when people are actually climbing. For the most part the drone has been very accurate - we have just found a new area in font with a potential 30 new boulders, this would not have been possible without the drone as the area is surrounded by thick trees and bushes."

Top UK boulderer and serial crag developer Dan Varian has also used Google Earth for scoping out new bouldering areas, in conjunction with other information gleaned from the internet:

"I've not used Google Earth for any mountain routes but use it all the time for bouldering crags and it has really helped with that. I wouldn't say that aerial imagery on its own is amazing as it only gives you one view and can give false impressions which can lead to red herrings. When used in conjunction with geograph.org.uk and other tools like simply searching for a nearby place name and looking at walkers' and sea kayakers' blogs it can be a great way of sorting the good prospects from the bad ones. I don't know any good bouldering developers who don't use aerial imagery and OS map data. Boulders and craglets are much better hiders than big mountain crags on the whole so you need to be a bit more wily to find them in this day and age."

Seasoned boulderer-turned-sport-climber Gareth Parry has also made use of Google Earth to check out potential new sport sectors near his home in Spain:

"I've used it a little to check out the access to possible new sectors at my crag. The crags can be accessed from above or below, one will be better than the other and Google Earth is very handy for determining this."

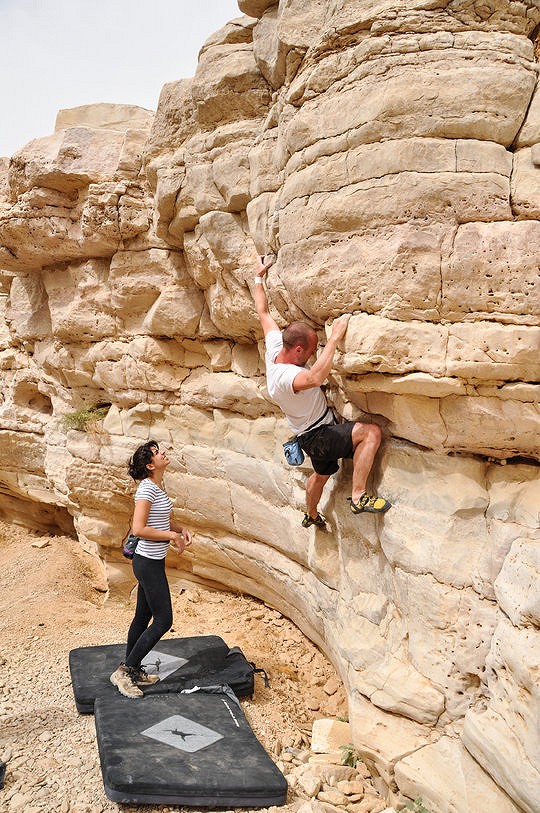

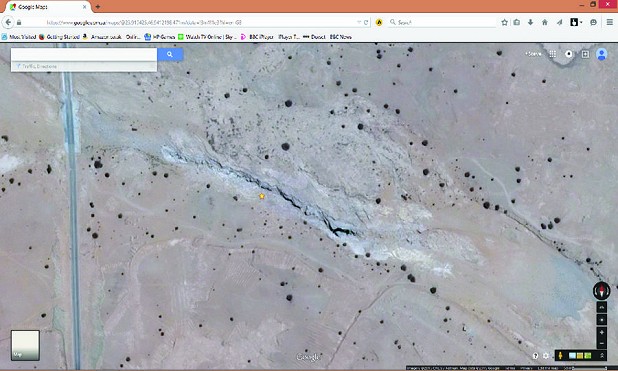

Further afield, Steve Taylor moved to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia from the UK a few years ago. Desperate to find rock to climb, Steve found himself resorting to Google Earth:

"Despite long searches on the internet for climbable rock in my new home, the only thing to come up was a few undeveloped granite crags over 200km from Riyadh, and a poor sandstone sport cliff just outside the city limits. There were tales of huge granite monoliths and stunning gneiss cliffs, but these were all well over a day's drive away. One of the local climbers spent many hours scanning Google Earth images for climbable rock in and around Riyadh and had so far come up with little of promise. One day he found a small wadi, displaying strangely white rock and clearly vertical sides, apparent from the sharp edges on the shadows on the satellite images.

"An exploratory visit showed it to be a promising bouldering venue composed of overhanging pocketed, limestone walls. Fast forward a year, and several storms had deepened the wadi by more than 2 metres, leaving an excellent bouldering venue with the odd route thrown in for good measure - Wadi Mawan is now the winter venue of choice for local climbers!

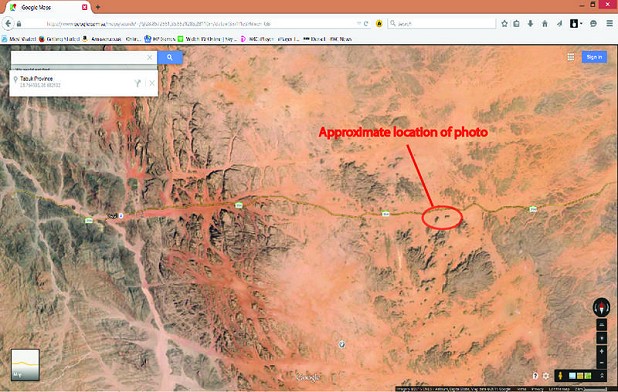

This discovery inspired Steve to start looking himself. Scanning a huge country like Saudi Arabia was never going to work so he based his searches on hints and clues from the internet and colleagues who had worked out there for several years:

"One workmate said that he had seen some climbable cliffs in the Tabuk region in the NW of the country. I was planning to be up there for meetings later in the week so resorted to Google Earth myself. Based on his loose description of the location I clicked along the route he had taken when he discovered these "magnificent" cliffs. Once again, clear shadows with sharp edges promised much."

"One evening, I drove the same route. It was all a bit disappointing at first, with cliffs of vertical, loose sand - was this what my colleague had seen? 20km later I dropped down into Wadi Badir on the road to Haql, just south of the border with Jordan. Suddenly the rock became solid. What I could see from the road looked fantastic, cliffs up to 300 metres of solid rock in the middle of a surreal desert landscape. "This looks like what I imagine Wadi Rum to look like" I thought. I hurriedly sent some photos to Hugh, another British climber in Riyadh - he concurred, as he'd actually been to Wadi Rum."

Steve gave some tips for budding developers:

"Clearly defined edges to shadows give an indication of how steep a feature might be from Google Earth. Also, users may have geo-tagged photos of these places - this will give a much clearer idea of whether or not there is climbable rock. Bing maps give much better resolution for some areas - certainly in the UK. For Saudi Arabia Google is best, though there seems to be an agreement with the government here not to show some of the roads on the terrain view - switching to satellite view shows some obvious dual-carriageways around the border with Jordan, so don't believe all that is is displayed!"

Thank you to George Cave and John Proctor for their assistance in reviewing this article.

Useful resources:

- George Cave's website with mapping resources.

- George's BMC article with hints and tips.

Watch a video of George Cave's TED Talk on using Google Earth for expedition planning below:

- SKILLS: Top Tips for Learning to Sport Climb Outdoors 22 Apr

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

Comments