Mick Conefrey, author of 'Everest 1922', compares the equipment used today on Everest with the heavy and primitive kit used in the expeditions throughout history...

When in 1924 the fledgling mountaineer Sandy Irvine accepted his place on the second British Everest expedition, he was sent a four page equipment list. Items requested included a windproof knickerbocker suit, a worn-in saddle, a rifle and a solar 'topi' pith helmet. Clearly a lot has changed over the last hundred years, but what does the equipment taken on the first Everest expeditions reveal about changing attitudes to climbing the world's highest mountain?

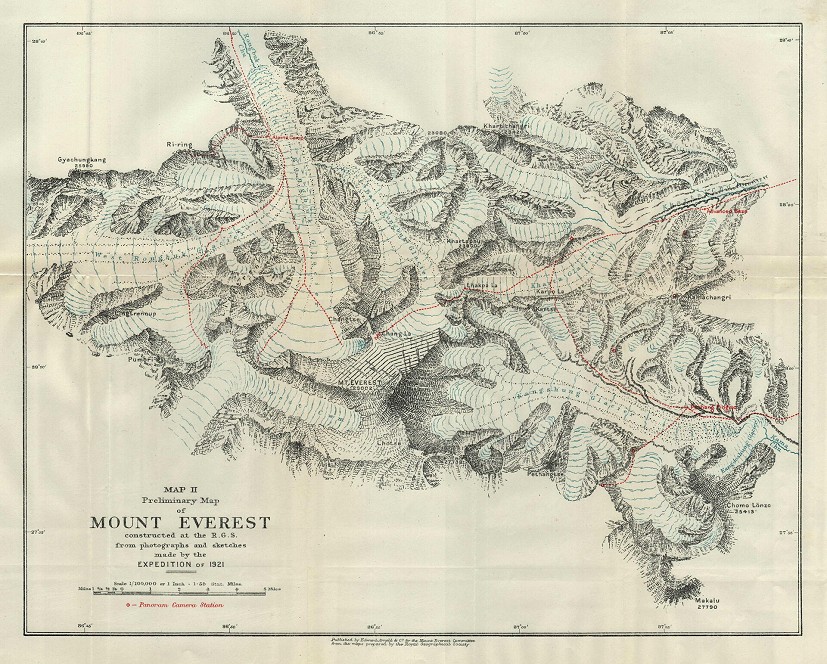

In the first instance, though a four-page list was much more comprehensive than any climber had been provided with in 1921 and 1922, when the team was initially advised to bring 'ordinary Alpine outfit on a liberal scale', it is tiny in comparison to modern day equipment lists. Adventure Consultants, the New Zealand company who are one of the big players on the commercial climbing circuit, have an Everest equipment list that runs to eighteen pages. Mountaineering, like so many other modern sports, has now become technology intensive, with new gear and equipment appearing all the time.

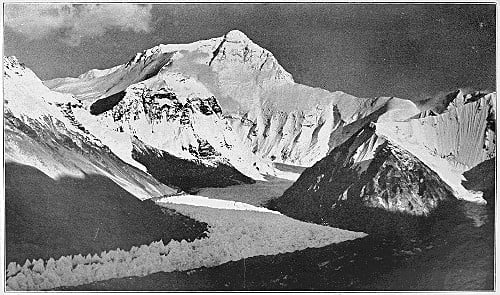

By contrast, in the first half of the twentieth century there was no real sense of the peculiar demands of high altitude climbing. No one talked about the 'death zone' or calculated the ideal calorie intake or liquid consumption for a climber at 28,000 ft. Himalayan climbing was seen essentially as a slightly more taxing version of Alpine climbing with European climbers consistently underestimating the challenge of the world's highest peaks. When George Mallory recced Everest in 1921, he really thought that the he had a genuine chance of getting to the summit on his very first attempt.

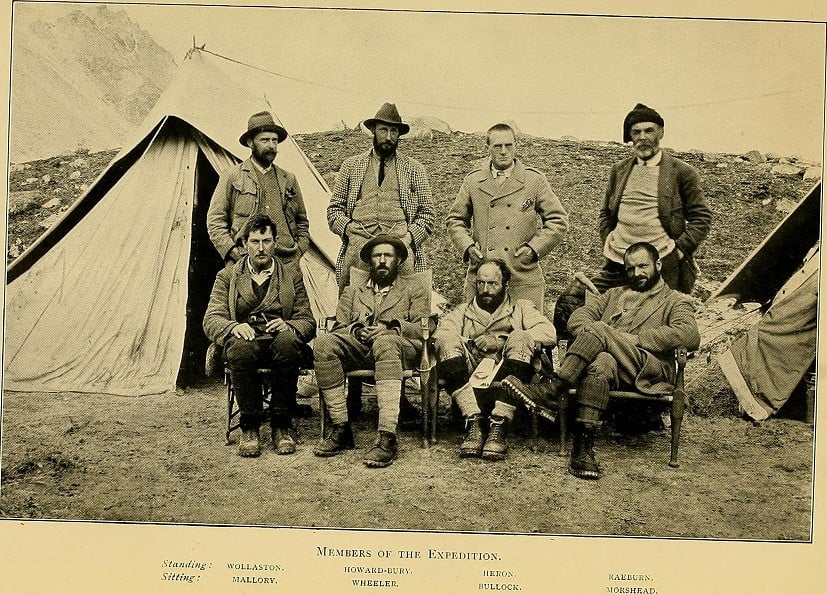

When it came to clothing, the basic approach in the 1920s was to wear the same sort of items that were taken on excursions to the Alps or shooting trips to Scotland: layers of tweed, cotton and silk, supplemented by windproof outer clothing. When the playwright, George Bernard Shaw, saw a photograph of the Everest reconnaissance expedition, he famously remarked that they looked like a 'Connemara picnic surprised in a snowstorm'.

The only real exception to this was the specially made clothing that George Finch took to Everest in 1922. A scientist, he understood that mountaineering clothing had to be light as well as warm for high altitude clothing, and commissioned a special jacket and set of pants made from parachute silk and goose down — the prototypical modern climbing suit. The other climbers laughed at him initially, until they saw how much warmer and more comfortable he was when facing storms on the Tibetan plain.

As for footwear, the early climbers wore boots made of leather or felt, studded with hobnails to add grip. The did have basic crampons but they rarely used them. It wasn't until 1953 that any systematic research was done into footwear. Griffith Pugh, the British Everest team's physiologist, worked out that 'one pound on the feet is the equivalent of four pounds on the shoulders' and commissioned several British firms to submit designs for the forthcoming expedition.

Ultimately, the boots that Ed Hillary wore on the summit were based on the combined efforts of 35 different footwear manufacturers. They had a kid leather outer skin covering a 1 inch thick layer of kapok insulation on top of a sole made from micro-cellular rubber and were specifically designed to be comfortable with crampons. For all their modernity, today they look very old-fashioned, with plastic replacing leather and newly developed synthetic materials dominating both clothing and boots.

Today's climbers arrive at the slopes of the Lhotse Face or the North Ridge, equipped with rucksacks full of harnesses, jumars, carabiners and ice-screws, but in the 1920s there was very little climbing equipment available. Mallory and the British team carried long-handled ice axes with wooden shafts, but apart from a few pegs to enable them to put up fixed lines, that was about it. In 1924 Irvine rigged up an improvised rope ladder with whatever spare timber he could find, to help the porters get up a particularly challenging ice chimney, but it wasn't until the 1950s that teams started to arrive in the Himalayas with aluminium bridging ladders.

The most controversial item of equipment in the 1920s was the oxygen set. Prior to leaving for Tibet the climbing team and the expedition's organisers spent a lot of time arguing about the ethics of using oxygen. Mallory famously described it as a 'damnable heresy', rejecting oxygen on sporting and aesthetic grounds; others were wary for more practical considerations, distrusting the technology and worrying that the benefits of oxygen were outweighed by the weight of the primitive sets then available. In the end, oxygen sets were used successfully by Finch and his partner Bruce in 1922, enabling them to break the world record reaching 27,300 ft. By 1924, Mallory had also been converted to the cause, but whether a failure in his oxygen set ultimately contributed to his death will never be known.

Today supplementary oxygen is taken for granted on modern day oxygen expeditions, but instead of the heavy steel cannisters and rubber tubes used by the pioneers, climbers come equipped with Kevlar oxygen cylinders and special ergonomically designed masks. The old debates refuse to go away though. While on modern day commercial Everest expeditions clients invariably use oxygen, it has become a badge of honour for elite climbers to get to the summit under their own steam.

Perhaps the most significant change though to equipping modern expeditions comes not in clothing or climbing equipment, but in the communications technologies that are routinely taken on modern expeditions. In 1922, the further the British team got from Darjeeling, their base in Norther India, the longer it took for messages to get back and forth. By the time they reached base camp on the Rongbuk Glacier in Tibet, it was taking between two four weeks to sound out messages and newspaper dispatches. They were carried by runners and riders to a post office and telegraph station a few hundred miles away in Phari; important news was then sent home by cable, personal letters went by post.

By the early 1950s communications technology was still fairly primitive, with postal runners still being used for the first leg of Jan Morris's epic attempt to get news of the first ascent back to London by Coronation Day. Four decades later, in 1990, Ed Hillary's son Peter, was able to telephone his father back in New Zealand from the summit, using a combination of radio and satellite telephone. Today it is even easier, with climbers tweeting and making video calls from the top of Everest, expecting to get news back virtually in real time.

Even more importantly, the telephones and laptops that are used to send messages back and forth are also used to receive vital weather forecasts. It's now customary for teams to wait at Base or Advance Base Camp for the optimum 'weather window' that will give the best chance of getting to the top, but in the 1920s climbers had to rely on guess work and local knowledge. They lived in constant fear of the arrival of the monsoon which would dump thousands of tonnes of snow onto the Himalayas and make conditions so avalanche prone that it would be impossible to climb. In 1924, George Mallory tried be a little more scientific, asking his sister in Colombo in Sri Lanka to send him postcards with advance warning of the monsoon's arrival, but like her letters, her cards travelled by post and arrived far too late to be of any use.

Ultimately of course, though good gear and equipment does give a climber a real edge, factors such as team morale and motivation are equally important. Whatever happened to Mallory and Irving, in 1924 Edward Norton got within a thousand feet of the summit of Everest, using one of those long-handled ice axes, dressed in tweed and Burberry wind-proofs and hob-nailed boots. He came down with a very bad case of snow blindness, having taken off his goggles high up, but otherwise he returned unscathed. As George Mallory famously said to a New York Times Journalist, climbers go to Everest 'Because it's there', not because they want to try out all the latest gizmos and scientific breakthroughs.

For all the clients who turn up on commercial expedition equipped with sacks full of the latest gear and equipment, equally since the 1980s other mountaineers have preferred to tackle the Himalayas 'Alpine Style', travelling light and using the minimum equipment necessary.

100 years from now, there will probably be a high speed railway that will go virtually all the way to Everest, and there will probably be some climbers using jet packs to get up to the North Col. But though the march of technology often seems inexorable, the urge to go back to basics, to climb as simply as possible with the absolute minimum of fuss is equally powerful. Long may that continue.

- ARTICLE: Kangchenjunga - The Last Great Mountain 25 May, 2020

- John Hunt - The Forgotten Hero of Everest? 14 Nov, 2012

Comments