Can we all keep cranking hard, even when life seems determined to slow us down? Inigo Atkin talks to Tom Randall and others as he looks at varying approaches to consistency in climbing and training in professional climbers, weekend warriors and everyday heroes...

We all reach the stage, no matter how good we are, at which our performance starts to dip. Sometimes it's an obvious consequence of changes in our lives - starting a family, a new job, an injury, tired old age. Other times it's more subtle. But there are those - and you will no doubt be familiar with at least one - who seem unable to do anything other than climb hard. No matter what life throws at them they endure, zen-like, and continue to climb way above your grade with seemingly no training or effort. From early on in sport, I was fascinated by the ability of some people, as I saw it, to perform at a high level with almost no effort at all. That external facade might conceal any number of interesting hidden talents - I wanted to dig deeper and find out a little more.

I should point out before starting that this is not a scientific study or training piece. Although there is some general awareness of data analysis, it is a predominantly anecdotal look at how good athletes maintain a high level of performance. I was interested as much in the stories and ideas people had as the physical factors at play. People will have other ideas, and other information, and may well know far more about it than me.

Science of Freedom

One of the greatest attributes of the sport of climbing is the freedom it engenders, as the title of Bernadette McDonald's new book about the mountaineer Voytek Kurtyka suggests. As a physical pursuit climbing has largely rejected the confines of organised sport for decades, promoting instead an almost artistic connection with wild places and the overcoming of seemingly insurmountable natural, economic or political barriers, facets that make it unlike any other 'sport'.

Yet this freedom and rejection of regimentation in some ways does climbers a disservice - it limits the potential for analysis or understanding of their feats. When Charlie Preston climbed the aptly-named 'Suicide Wall' in 1945, or when Lynn Hill freed The Nose, these were quantum leaps in the sport, like the sub-10 second 100m or the Fosbury Flop. Yet whilst the achievements themselves were applauded, the physiological, mental and logistical barriers that had been overcome were simply not discussed at the level they would have been in another sport. The complexity of the movements and the indeterminate physical qualities required to be a 'good' climber created a culture where the experience was tantamount, and (at least in many circles) the 'dirtbag' was king.

That is until recently. A changing approach to the sport's relationship with regimented training and sports science, spearheaded by pioneering climbers like Jerry Moffatt and Wolfgang Gullich, has led to a professionalism in climbing in which it's possible to start analysing the performance behind these achievements, even if some climbers choose to eschew those methods.

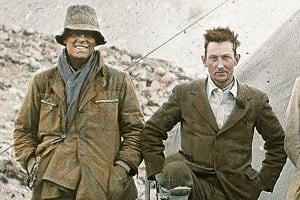

One climber and trainer who has invested heavily in the business of analysing climbing and its physiological building blocks is Tom Randall. He is perhaps best known for his collaborations with Pete Whittaker on their 'Wideboyz' projects - films documenting their attempts to climb the world's hardest cracks. But he is also a trainer and coach extraordinaire, having worked with top junior and senior athletes for years. He built the Lattice board as a testing tool in 2011, and brought it to the market as a commercial product not long after. Its phenomenal success since then (it is now available in more than 20 centres in 6 different countries) is a testament to how many climbers believe that science, rather than art, is their route to 'freedom'.

A holistic view

That belief is not without conflicts however. Hazel Findlay might be said to span the boundary between the 'freedom of the hills' and the cutting-edge of sporting prowess. A trad-wad by nature, with a 'rack' of hard ascents in the high Extremes, she also boasts Britain's (joint) hardest sport grade by a female climber, with her ascents of Mind Control and Fisheye (both 8c), as well as having plenty of big-wall and alpine feathers in her cap, such as her recent free ascent of the Salathe Wall. Famed for her laid back attitude and focus on the mental game, rather than heavy training loads, she regularly defies simple explanations for her continued success.

Yet Tom thinks that the story behind Hazel's consistent performance is roughly similar to the things he sees in every athlete performing at a high level, both those he tests and those he observes elsewhere. He talks quite a bit about 'rounded profiles', and with Hazel he makes it very clear why he believes she is so successful:

"If we compare someone like Hazel, that typically we would look at as making a lifestyle choice with their climbing...yet still performs at the top end, compared to someone at the wall four times a week, smashing sets...the difference between those people is that if you look at Hazel's physical profile, [she] will have a very average profile but with no weak areas. But then you will look at certain facets of that person's performance, say their mental approach, and she lies in the #1 spot of any woman or man - absolutely right at the margins of mental attitude."

Laying aside for a moment the implications on performance of that mental strength, it's clear from speaking to Tom and looking at the data he has collected, that the 'rounded profile' sits at the heart of both what they do as analysts, and what top climbers are doing out on walls everywhere.

"The biggest killer of performance is a gap in the profile". Whilst Tom's wording might seem dramatic, it's clear that all the data he and his team have collected backs up his claim. They've have tested hundreds of climbers, of all disciplines, and Tom thinks they are yet to find an elite performer who is not physiologically consistent in all the areas looked at (finger strength, aerobic and anaerobic capacity, conditioning and movement economy). In fact, it seems like quite a lot of climbers are performing significantly below their potential due almost entirely to a serious deficiency in one area of their physical profile.

Yet despite the obvious correlation between the figures Tom is capable of producing and performance on rock or plastic, it would be short-sighted to suggest that's all there is to it. If everyone's climbing woes could be solved by a bit of fingerboarding or some 4x4s, there would a fair few more Adam Ondras in the world. One big area that is partially (but by no means completely) eclipsed in a Lattice test is the economy of movement. Tom actually conceived of the board with what he describes as "100% movement efficiency" as a given - ie it was for elite climbers who already had near perfect technique.

It is perhaps unsurprising that at the top end, it is rare to find anyone without an arsenal of techniques and movements that are finely-tuned. An oft-quoted example in rowing, a sport I'm intimately familiar with, is about using 'light hands' - one coach would make his athletes sit in bed at night rolling oar handles (dissected from old oars) lightly through their fingers to embed the movement until it was so second nature they would never forget it. Watch the timing required to pull off a running dyno in a bouldering World Cup, or the subtlety of hip and heel movement required on a smooth gritstone mantle, and the parallels become obvious.

Then again, good movement can only take you so far. Perhaps the final portion in the bizarre Venn diagram of continuous, high-level achievement is something touched on earlier when discussing Hazel Findlay - the head game.

To provide some contrast and comparison with the mental approaches taken by climbers, I spoke to Simon Fieldhouse, a former international rower. Simon was a very different type of athlete from most professional climbers, and he experienced the 'sharp end' in a very different way - often from the bow (front) seat of Olympic and World Championship crews in fiercely competitive 6-boat races. He described the "tenacity" needed to cope in that kind of environment: "I had a fear of failure, where a sub-par performance on a test might mean I was f***ed, but conversely that also pushed me on. When I made particular breakthroughs, I felt like I could pick anyone off".

Although the practical application of that type of head game might not be familiar to climbers, the sentiments - of being tenacious, and breaking through plateaus or barriers - certainly will be. In climbing, the challenge is not just to balance all the delicate elements of mental approach when it comes to training and physical performance, but also to combat fear and convince ourselves of our own over-riding self-confidence. All this is well and good - but what happens when real life catches up?

Comebacks, clip-ups and consistency

As the route at Kilnsey suggests, we can't all be sponsored heroes. But perhaps some of the wisdom espoused by Randall and others can be applied to what everyone else is doing.

A recent meme by Instagram funnymen-in-chief @RawkTawk suggested that for most of us, once you pass 30 "every season is comeback season".

Someone who might be able to attest to the truthfulness of that statement is Dylan Fletcher, a man whose own Instagram handle says it all - he's on @constantclimbingcomeback. His achievements as a climber are impressive - he's bouldered and redpointed into the 8s and put down a variety of hard trad lines to boot. Yet by his own description, he is simply a normal guy, with two young children and a job that pulls him around the country and forces him into unsociable hours: "I took three years out from climbing - the impact that has is enormous, and coming back to it is no piece of cake either. An unpredictable work schedule and young kids means sleep deprivation, and a seriously impaired ability to structure my training consistently". Like Tom, he believes consistency is the name of the game - but I think the consistency he is talking about is quite different.

The 'normal' limitations most climbers experience, such as family and job commitments, put direct demands on our two most precious resources - time and energy. Overcoming those requires a particular kind of focus, and a broadened definition of what counts as 'consistent'. I also spoke to Rupert Davies, who told me that he sometimes squeezes in half hour training sessions, while using the breaks between attempts or reps to work on his laptop, which allows him to maintain climbing fitness around work and his young family: "It sort of works." The seemingly frenetic pace is sharply at odds with both the professional approach to training and recovery of today's elite, and the 'dirtbag' lifestyle choices of some of those climbers who still occupy the sport's upper echelon. Yet it is a pace that probably looks familiar to most readers.

Rupert, who along with John Coefield quite literally wrote the book on Peak District Bouldering, is a barrister and father to two young boys. His approach to the commitment needed to tick hard climbs is not dissimilar to Dylan's - it's all about the time you put in. Although he stresses that "I don't feel like I've ever climbed particularly hard", he's redpointed 8c, bouldered V13 and done trad E7/8. He achieved most if not all of these while working. But since converting to law and passing the bar, and starting a family, the time available to him has shrunk even further. He therefore sees training as key and is convinced of the need to keep "plugging away...the less time you can take off the better".

Perhaps the most telling example of how that is true for him actually has nothing to do with climbing at all - speaking of his work as a barrister, Rupert points out: "When I spend less time in court, my advocacy ability drops off". Whilst it seems practically reductionist to reduce ability to such simplistic terms, his point will resonate with almost everyone: more time in = improvement, less time in = deterioration. Simon Fieldhouse broadly agrees, stressing that the application of time and energy not only underpins sporting achievement, but also carries sideways into other pursuits as well: "the rewards and return for what you're putting in largely come as a by-product of the volume of training or preparation you are able to complete".

However, Simon's work in the financial sector and his experiences of competing on the international stage as an oarsman also led him to the conclusion that there is more to 'high-performance' than simply putting in your hours. He talked about his current experiences racing with other 'old guys' - his crew is made up largely of ex-Olympians and former World Champions: "everyone has done something". When racing younger, fitter and stronger opposition they often find that their collective nouse stands them in remarkably good stead - they are tactically superior, and not afraid to dig deep even when it's painful. Having successfully applied that nouse to sport, he finds it easier to apply it to his work life, and the same goes for teamwork.

As life challenges us to fit our pastimes around everything else, we are forced to moderate our approach. For many climbers, this means a change in style - more clipping of bolts rather than long trad epics, or short sharp bouldering sessions indoors rather than an evening out on rock. Yet the overlap between Lattice's professional analysis, and the outwardly more amateur (in the traditional sporting sense) approach of 'normal' people, is in fact huge. Rupert, who still maintains an equal or very similar level to the peak he reached several years ago, is trained by Tom. In the final part of this piece, I'll try to draw together why that overlap matters, and what it might mean for the rest of us.

Statement of eternal youth

Tom Randall was quick to point out that there exists a significant correlation between volume of training and continued, serious output: "a very common marker across athletes moving from junior through to senior...is that the ones that become true superstars have this unnerving capacity in their teenage years to take whatever workload you give them". It should come as no surprise that time and effective volume equal success - the '10,000 hours' theory is one that has become common parlance in sports science in recent years.

But the good news is that if you don't have 10,000 hours to spare (it's about ten years' worth of training, in case you were wondering) you can still crank really hard. Tom also refers to what he describes as a "high sporting or training IQ" - a brilliant way of describing how some athletes are able to make the most of their limited time in the gym or on the rock, and improve substantially as a result. He isn't prescriptive about what that high IQ might look like, but I've taken the liberty of drawing some conclusions from what he had to say, and what the other highly experienced athletes I spoke to thought about it.

It is crystal clear that everyone with any interest in performing at their chosen endeavour, be it climbing, rowing, running or studying, is appraised of the value of being consistent. But that's such a broad term it is almost meaningless - it's hardly revolutionary training advice to suggest that consistency is key! But what came out of the conversations on this topic was how many types of consistency went into performance. What was particularly fascinating for me was how different individuals, when asked exactly the same questions, all returned to the consistency theme - but from completely different angles.

Tom talked about the importance of physiological consistency - keeping energy systems topped up to the right levels and in balance, staying injury free and maintaining good movement.

Rupert stressed the value of being consistent in how you applied your time: "with climbing I've found a good rule of thumb is that it takes the same time to get back to your old level as the time you had off".

Simon answered largely on the mental side of sporting achievement, about how he had to develop a sometimes ferocious approach to competition, while still remaining focused on himself: "You might beat someone on a given day, but that didn't mean you were better than them. I had to focus on my own progress".

Looking at the interplay between these different aspects of success and achievement seemed to suggest that somewhere in the middle of all these elements is where each individual's 'peak' lies. Yet reaching it requires a presence of mind and commitment that is not always obvious or easily attainable, because life frequently catches up with us. Freddie from The Boardroom talks about the concept of 'cascading failures' - normally an expression that is applied to will power, it neatly encapsulates the difficulty of getting all of these things to align if you a 'normal' athlete. Freddie points out that "a study showed that trying to make more than one significant change to your routine drastically reduced your chance of sticking to any of it. For athletes whose routine is already adapted to support training and performance i.e. diet, sleep, scheduling etc, making a single significant change to their training is far more manageable".

'Bold'. 'Snappy'. 'On the sharp end'. 'Tenacious'. These are expressions we throw around in climbing, but the feeling they denote is common to most sports - I've heard them all used in rowing, in pretty similar contexts. They attempt to encapsulate what it's like to be performing at your max - the feeling of latching the good hold by your fingertips, or winning the race by a tiny margin. That feeling is something that is common to us all, regardless of level. It's not just about performing – the feeling of everything slotting into place produces a similar satisfaction.

Although this piece has taken some input from a variety of high-achievers, none of them are super-humans. Rather they are normal sportspeople who have managed to fine tune some of their best skills, and who have come up with a personal approach that allows them to maximise not just their performance, but their enjoyment. It is perhaps there that the greatest lesson lies: "do things you enjoy and are good at. The two will probably coincide", Rupert says. I will not quote Alex Lowe, but I'm sure you all get the point.

Comments

Chris Preston not Charlie made the fa of suicide wall after top rope practice.

James

I enjoyed this article, thanks.

Has anyone trained on a lattice board - why is it advantageous ? I would have expected that being so regular - it would not help with real rock ...

On the same theme I question the usefulness of comparison with rowing - which requires machine like precision; not that we don't need precision - but every move is different on real rock.

It is precisely its regularity that makes it advantageous. Training for climbing has been in the dark ages - espeically compared to running or cycling, or similar endurance sports.

Training for running is much easier: it is well known what works, and is much easier to measure and record the main variables - that is, volume and pace.

In comparison it is almost impossible to do the same with climbing. Even training on a bouldering wall which is at least a fairly controlled medium, it is hard if not impossible to measure and record the activity. Made even worse by the fact that walls insist on resetting the problems every few weeks.

So the advantage of something like the lattice is you can use it to measure progress in training the main energy systems, aerobic and anaerobic (I'm simplifying here). Ultimately if you can hang on and endure for ever you can climb almost any long endurance route.

Of course, you are right that climbing is very complex activity in terms of moves and timing (not to mention mental aspects etc), so you have to train all those other angles by doing real climbing. Sort of like in running where ideally you run offroad and do XC for strength - though of course running is a much simpler activity.

ps. rowing doesn't just need precision. You have to work well as a team if you're in a crew, and there's all the mental aspects of racing.

Not when you redpoint it isn’t.

Water, like rock has endless types of surface to play on. Rowing is one example of a water sport, sport climbing is one example of rock climbing.