There's something about poetry that tends to freak people out. Maybe it's something to do with the way it's taught in schools, or that prose is to more people's tastes, or perhaps it's just that we don't know what to look out for? Either way, poetry seems to elicit an extreme reaction, particularly from our audience on UKC. In this interview we spoke to David Wilson, author of The Equilibrium Line, about his thoughts on this. What came back were a series of down to earth, thought provoking answers which give an insight into what poetry is and how we might approach and engage with it.

Whilst a great many of our audience understand prose, whenever we publish poetry there tends to be something of a 'reaction'. It is - for one reason and the next - a medium of marmite. You began your own writing career with fiction and short stories before making the move over to poetry - why did you make the change?

For much of my life I had a negative reaction to poetry. Too many poems felt obscure and pretentious. A poem should welcome us in, not put us off. But I was just reading the wrong stuff.

I came to writing poetry by chance after seeing Midsummer, Tobago by Derek Walcott on the wall of a hospital waiting room in Leeds. It just bIew me away and I wanted to give poetry a try. After a while I found I was writing more and more about climbing.

Poetry is well-suited to the climbing experience. Intensity, balance and use of space are integral to both. A climb is something we see in front us, like the single page of a poem. And, by its nature, climbing offers up metaphors – about height, scale, summits, drops, risk, falling and finding balance.

Actually, quite a few climbers write good poetry, including editors and reviewers for magazines in the US and UK. One of them, Andy Clark, has written two features on poetry for Climber. And you just have to look at UKC logs to see some wonderful lines. Setting out for a big day on the Ben, someone wrote, 'Caffeine-fuelled excitement catapulted us up'. I love that.

There is a rich history of poetry within climbing and mountaineering. Whose work in particular have you enjoyed - both past and present - and are there any individuals that have had a particular influence on your own style?

The person I've learned most from is Helen Mort. Her long poem The Climb, in Vertebrate's Waymaking is a superb riff on where a climb actually begins, not just at the bottom of a route – under cigarette-smoke sky/ below a rock's mossed fin − but other places in the heart and head, for example:

The climb begins

in your ice-blue Ford,

the wheels' manic spin,

Your face framed

in the rear-view mirror briefly

like a lost twin

You can hear the poem read in the programme Give Me Space Below My Feet about Gwen Moffat, (available online as a BBC audio).

Take a look at her poem Angler in the online magazine BASE. It's an expression of what it means not to climb, like we all experienced during lockdown. It starts:

and since I don't dance these days

the movement stays bunched

in my calves and fingertips,

knotted in my shoulder blades

An Easy Day for a Lady (available at Guardian online), re-imagines the Alps. As a contrast, you might hunt down Michael Roberts' poem La Meije 1937 for a glimpse of an era when climbers (male of course) were seen as role models for radical change.

Andrew Greig is worth a look, and I especially like his poem Freefall. That's not about climbing but I think only a climber could have written it. A man bumps into an ex-girlfriend at a party. She once told him that to find the depth of a well you drop a stone and start counting. When she asks him how he's been, the poem ends:

I grin and don't know where to put my hands,

For I am falling, and it's been years,

And I've heard nothing yet.

Mark Goodwin is interesting and bold in his experimentation. And for a poem about a day in the hills, nothing beats Norman McCaig. Climbing Suilven starts:

I nod and nod to my own shadow and thrust

A mountain down and down.

Between my feet a loch shines in the brown,

Its silver paper crinkled and edged with rust.

So there's plenty of good climbing poetry, but there's also the equivalent of a lot of unclimbed rock. Rather like having your own secret crag, many lines are still to be found.

"David Wilson's lyric poems are beautifully-crafted, heartfelt, and extremely relatable. They chart a lifetime's fascination with rock climbing and mountaineering, and pay homage to presiding spirits in the climbing world. Each poem is like a first climb – full of fear and joy and gratitude."

– Helen Mort, 2019 Book Competition Jury

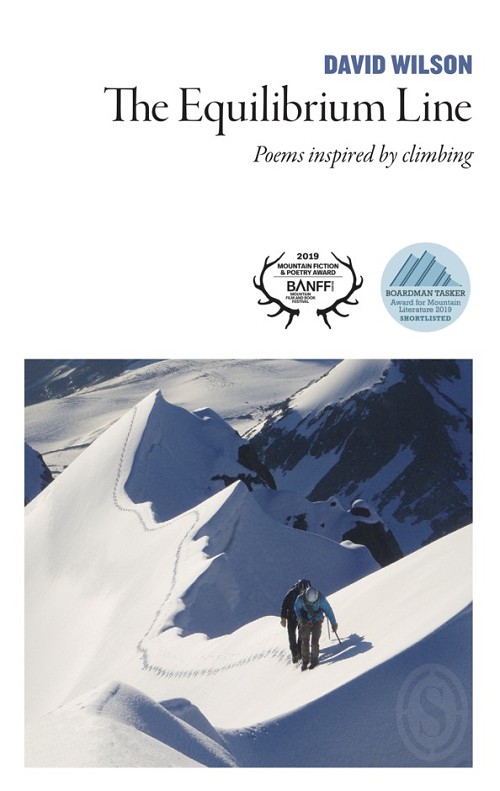

Your 2019 collection - The Equilibrium Line - won the Mountain Fiction and Poetry Award at Banff and was shortlisted for the Boardman Tasker. In it you explore a range of different disciplines, from bouldering (both indoors and out) to trad climbing, hillwalking, winter and alpine. How does each medium differ in terms of how you write about them?

Hmm, I haven't actually thought much about that, only that I wanted to celebrate different activities. Climbing walls have stripped climbing down to the sheer pleasure of movement, and cut out all the tricky stuff like feeling cold and getting gripped and not having access to espresso machines. In contrast, winter climbing in Scotland seems inseparable from the weather. In fact, dreadful weather is often prized as part of the true experience. So writing about different disciplines can have a different feel.

"Risk, falling and finding balance" are quoted as being major themes throughout. Whilst climbing is undoubtedly a central part of the collection, you also explore a great many events that occur around it - bivouacking being one example in particular. Is it important not to get too focused on the activity alone and broaden your horizon?

Don Whillans once said that when you're lying by the swimming pool in Chamonix you long to be in the mountains and in the mountains you long to be by the pool. It's all about the dynamic between the two. I was looking to explore what climbing has meant me. And to do that you have to set climbing in the context of the rest of your life. For example, I wanted to explore what climbing meant to me when I was stuck in an office or during a time of loss or just needing to get away. My poem The Problem starts with the line, As if it were an answer, I drive north/ past Pulpit Rock and Rannoch Moor and ends with

I hook and teeter on smears of ice,

nearly barn-door, reach higher,

place my bet, fully exposed

until I'm clear and over the worst,

to gasp and tremble and roar

as my heart emerges from the cave

where it's crouched all winter.

So, it's hard to separate climbing from the rest of life. Above all, though, I just wanted to express the joy and sheer fun of climbing.

"Risk, falling and finding balance" are quoted as being major themes throughout your collection. Does setting out a distinct set of criteria or concepts you're looking to explore help when writing poetry?

When I'd written maybe twenty poems, I started to wonder how they related to each other, what seemed to fit next to what. Balance and equilibrium seemed a continuing theme. The changing equilibrium line on alpine glaciers is a measure of climate destruction. And of course we all judge 'where to draw the line' in regard to risk, which is so brilliantly handled in the film Meru. 'The Equilibrium Line' seemed to link everything together. And we can't be blind to the wider context in which we climb: environment, discrimination, history. So I started to think about what else I might need to write a coherent book.

Following on from the above, where would you recommend our audience start with writing their own poetry?

There are many approaches but I'll suggest one, using as an example an early poem I wrote:

Bivouac at Harrison's Rocks

Leaves turn from green to grey.

On the breeze, a scent of hops.

A star appears. A bat.

Beyond silver birches

a train sounds its two-tone horn,

slows for a bend, disappears.

We're fifteen years old

with apple pies, cans of Sprite,

and dreams of the Eigerwand.

Above our ledge a sandstone roof,

below us the drop. Not far

but far enough.

So, here goes with a few suggestions.

Write about what matters. Otherwise a poem won't get off the deck. But do it through a particular experience. That could be a memorable climb, like your first lead or solo. Or you could give yourself a head start by picking something that lends itself to more than one meaning, like 'a problem I worked on for months' or 'the first time I fell' or 'the crux'. I'm intrigued right now by the phrase 'I climbed out of my skin'. Anyway, I simply wanted a poem about the fun of getting away from home and school, and chose one experience.

Make notes in lines, little units of maybe 6 – 12 syllables, like writing a song, which is what a poem is. For example, a line or two about what you see, lines about what you hear, touch, smell, etc. Take us there, put us in the movie. Perhaps a line or two about who else is there, what you are feeling or thinking or dreaming about, maybe a question you're asking yourself. Work really fast, almost without thinking, write whatever comes, like listening to a voice inside yourself (if that doesn't sound pretentious).

Go through these notes and look for the heart of your poem. What moves you? Is there is an image or description you like? What lifts you off the ground as you read? Someone said that what you feel when writing is what the reader will feel when reading.

Is there an image that you could develop, follow to see where it takes you? Climbing is full of things that work as metaphors, for example, knots, rope, attachment, falls, blizzards, mist, topos, the drop.

Is there a starting line that seems right? The start should welcome us in and make us want to read on. For example, take a line from M John Harrison's novel Climbers. It was something like, We drove West into the immense potential of the day. I guess we could all write a poem from that line. I'm immediately back to driving down the M4 early on a Sunday morning to climb at Avon Gorge: the big CND sign on the slabs, the mud banks, the ice-cream van at the top of Main Wall, the search for subtle limestone holds (in the days before chalk)…

Is there an image you might end with, perhaps something open that leaves the reader with space to carry on making the poem in their own head? I thought 'the drop' would work for Harrison's Bivouac. Another poem, about weighing up whether to continue or retreat on a climb, ended:

November at work without a fix,

a glimpse of where the pitch might ease,

Her face at a window, Dad come home,

and you not knowing where you've been

or how to get back from it.

Now draft the poem, cutting out inessentials. I'd made notes about being up at 5.00 a.m. and having hours with the climbs to ourselves, but all that started to sap energy from the poem. I like the idea of the eloquent detail. When Guido Magnone made the first ascent of the West Face of the Dru he calculated that when he could see the swimming pool in Chamonix he'd be past the major difficulties. He wrote, 'I turned round and could see the whole of Chamonix spread below me'. That's all I remember of that book. Choose the eloquent details, cut the rest. That swimming pool again!

Another good tip is to read your poem aloud, or better still, take it for a walk or run or bouldering. Does it have rhythm? How does it sound? A tip for a good line is to vary the vowels in it a lot. If there are bits you can't remember, best leave them out.

Moving on from there

Perhaps the trickiest thing is to find a structure to hold your writing. The truth here is that if you don't read well, it's much harder to write well. But one huge benefit of poetry is that it only takes a minute or two to read a poem! Try googling poems by Billy Collins or get hold of Kenneth Koch's New Addresses or Helen Mort's No Map Could Show Them. You'll soon see 'recipes' you might follow.

A structure I often use is Once/But now. It works if what a place or person means to you has changed. I used it to write about Everest: 'Once it was Chomolungma…, now it's like Elvis near the end'. That poem came from the luck of reading Mountains of the Mind at the same time as a book called Dead Elvis. So stay alert to connections and what's going on inside your head.

Putting 'But' or 'Even so' into a poem often helps it develop. I love Raymond Carver's small poem Late Fragment that starts:

From this life

Even so?

That's raw and brave. How about putting 'climb' or 'trip' or 'day' into the poem instead of 'life'? What would you start to write about?

Another approach is to write about something that matters as if it's a person. I wrote about The Mont Blanc Range, starting

the slight shudder as it docked.

I did it the same for writing a poem addressed to mediocrity:

stuck half-way up a lower grade climb.

We'd met off and on over the years …

An address form would work well for looking at that elusive thing called confidence or how you feel about your climber's body (now and then) or about competitiveness or an old piece of kit you can't throw out.

Finally, I am a complete unnatural when it comes to poetry. I've been trained my whole life to think and write logically. If I can do it, anyone can. But it's also to do with motivation. I think a lot of people turn to writing later in life, perhaps to relive the experience, stop the details dropping into oblivion or communicate what it means to others. You can get as much delight from a poem you've written about a climb as doing it. That feeling of rising above the ground.

Otherwise, why bother. You'd be better off climbing!

Comments