Winter climbs often have long, poorly protected run-outs with potential for high impact forces in the event of a fall. Protection can be hard to find and also it can be less than 100% reliable. It can also be more spaced out than might be the case in summer.

These factors can lead to a situation where if the climber were to fall - and given that some of the protection may be suspect and could fail - the safety chain (ie. belay) could have to deal with high impact forces caused by a long fall.

Although this situation is potentially manageable, another factor to add to the equation is when the main belay anchors are themselves suspect, a not uncommon occurrence in winter.

A long fall with potentially high impact forces onto a suspect main belay can have serious and potentially fatal consequences for the whole party.

So what options do we have to minimise the impact force on the belay in the event of a leader fall above the belay?

Good practice would suggest placing a runner to protect the belay before or as soon as leaving the stance, thereby ensuring that A) there is no chance of a Fall Factor 2 and B) that the belay plate (being oriented for an upward pull) will be correctly oriented if the leader falls just above the stance. However for this to work it makes the assumption that a bomber runner is readily accessible. As anyone who has climbed in winter knows this is not always the case. This article looks to explore and discuss some of the issues around how we protect our main belays in winter thus ensuring or reducing the consequences of a leader fall onto the belay.

Protecting the belay

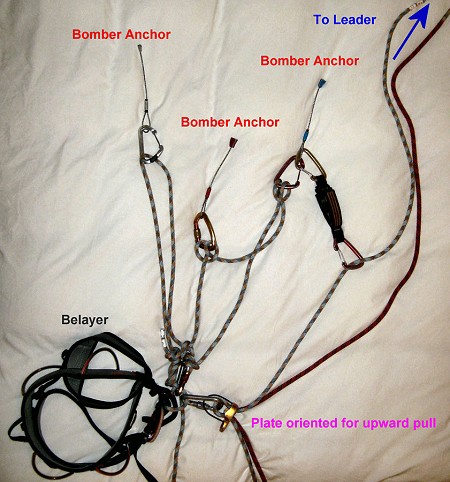

First of all - back to what I would suggest is good practice, summer or winter – as shown in Figure 1 is protecting the belay with a bomber runner, ideally before leaving the stance.

The underlying reason for this is; as there is less rope run out at the start of a pitch the impact forces in the event of a fall can be significant (there isn't as much rope out to absorb the impact). Add to that how the belay plate is orientated e.g. for an upward pull, then we can see that if we don't protect the belay, the team (and belay) will be facing a Fall Factor 2 onto the main belay with the plate wrongly oriented for the resulting fall i.e. a downward pull. Not good.

So what could we do to avoid this situation? Well there are a range of possible options assuming that we can actually place a suitable runner. These options are ranked in order i.e. most effective first.

This is the first, and would be my preferred, option - place an early independent bomber runner before leaving the stance as shown in Figure 1 (above). You can have the belayer's plate oriented for an upward pull, thus if the leader does pop off when leaving the stance not only do we reduce the potential impact force onto the belay but the belayer has a better chance of holding the fall. Off course for this to work that independent runner has to be bombproof. If it fails then we are back to holding a fall with the plate oriented for an upward pull but trying to hold a downward force, again not good.

However, if there is no independent runner option before leaving the stance then you have choices to make, or rather judgements.

Option 1: If you see a bomber anchor option just above the stance you have to weigh up how likely you are to pop off before placing that runner, perhaps with the plate oriented for an anticipated upward pull, and the consequences to the team as a result. This option is perhaps appropriate if there is little or no technical climbing to reach a place from which to place that runner and there is little or no chance of being hit by any falling debris, spindrift etc and falling before placing the runner.

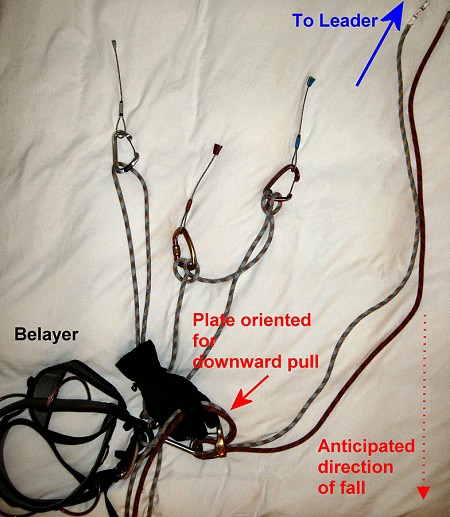

Option 2: You could have the belay plate set up as shown in Figure 2 for a downward pull. This does not prevent a Fall Factor 2 onto the belay but at least there is a chance of holding the fall dynamically (more on this later). If you do place the runner then the plate will also work for holding an upward pull. However care must be taken with this to ensure that the belayer is not spun around and down in the direction of the down fall as this could injure them (possibility of lower leg injury).

Option 3: This option is more contentious and requires very careful judgement... Use one of the main anchors on your main belay as shown in Figure 3 (above).

Now, before using this option there are several assumptions you have to make:

All the best (bomber) placements have been used for the main belay.

There are no other bomber runners close to the stance and the next possible runner options are a distance away up technical ground.

In this case I would clip one bomber anchor on the belay and use that as my first runner. This HAS to be a bomber piece.

Why does it have to be bomber? If this piece fails whilst holding a fall then you have weakened your main belay anchor set-up and are now about to have a large impact force hit the belay with the plate oriented for an upward pull rather than a downward pull. In the illustration I've clipped a shock absorbing extender to reduce any potential impact force on the runner/anchor.

On leaving the stance I'd be looking to get gear in as soon as is practicably possible. This method is less risky if the main belay is made up of several pieces, hopefully all reasonable to bomber i.e. you've used all the best and bomber placements, so that using one piece does not necessarily compromise the belay unduly. You are trading any potential downside with this option with the fact that the belay plate will be correctly oriented for an upward pull. Of course if the belay anchors are not the best then all bets are off and you might want to think about other options - like the leader must not fall!

Whichever of the options outlined above you use, and ultimately that judgement call is yours given that every climbing situation is unique, you want to be placing as many good runners as you can early on in the pitch. The less rope out the less rope there is to absorb the impact force and therefore the greater the potential impact force. So lot's of runners help keep the fall factor low and thereby reduce the impact force on the safety chain as a whole.

Dynamically Arresting Falls

So given that the reality in many winter climbing situations is long run outs between (possibly suspect) protection with the potential for long falls then how we arrest, or hold the fall, has implications for the integrity of our safety chain. Ideally we are looking to dynamically arrest a fall thereby reducing the potential for a catastrophic shock loading on our anchors. Obviously factors such as rope diameter vs belay device (i.e. rope diameter is compatible with the belay device slots), rope system used (e.g. double ropes vs single rope vs twin rope), length of fall type of fall (freefall vs tumbling etc) all have an effect on the impact force of the resultant fall. In any case being able to dynamically arrest the fall will assist in lessening the resultant impact force.

In winter ropes becoming wet then freezing can be a common event. In no time your supple, easy to handle climbing rope can take on all the handling characteristics of a steel cable. This can be frustrating as you attempt to force what feels like a 13mm rope into the 9mm wide holes on your belay plate.

If you do manage to insert the rope into the belay plate, holding a fall dynamically can be problematic, as the ropes will jam in the plate causing a potentially serious shock load.

If, and when the climbing rope(s) freeze an option to avoid this angst is to use a body belay. This method allows a reasonably dynamic i.e. gradual arrest of a fall even when the ropes have turned to icy cables. Care must be taken to ensure the live rope (i.e. the rope going to the leader or second) must be on the same side as the climber's attachment point to their anchors. If the rope is incorrectly placed the belayer attempting to hold the fall can be spun around thereby losing control of the rope – not good.

This all works fine if the fall creates a downward pull on the belayer but if the leader has placed a runner above the stance then the belayer (providing the runner holds) will have to deal with an upward pull. Holding an upward pull is a bit harder to do with a waist belay compared to using a belay device, especially if you are unpracticed at this. To make this a bit easier you can attach a krab to the front of your harness loop and run the live rope through this thus preventing the rope being pulled up and behind you.

Protecting the main belay is key to minimising the impact force on the belay in the event of a leader fall. Your first and best option is to place an independent bomber runner ideally before setting off from the stance. If this is not possible then you will have to explore other appropriate options which could be orientating the belay plate for a downward pull, clipping a bomber anchor on the main belay (assuming the other anchors are all equally bomber) or making a call about how far above the main belay is your next runner opportunity and how good it will be. Ultimately how you manage this situation is down to your judgement of that situation in that time and place. All things being equal the other common winter climbing scenario is little or no good protection, poor anchors and long run-outs. In this case the old adage – "The leader must not fall" will hold true.

Top Tip 1

Encourage bored seconds not to idly swing around off the main belay given that some of the anchors may be dubious. Main belay anchor failure would rouse even the most catatonic of seconds.

Top Tip 2

Use shock-absorbing extenders on dubious runners to help reduce the impact force on the piece of protection. But mind, they will not magically turn crap runners into bomber runners...

Fall Factors Quickly Explained

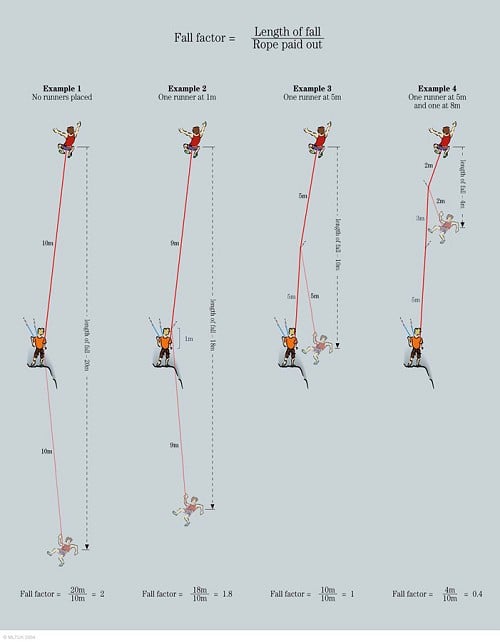

When you fall off a route the single piece of kit that will do the most to reduce the impact force on your safety chain (anchors, climber, belay etc) will be the rope. The rope does this by absorbing the energy of the fall by stretching and absorbing some of the energy of the fall. In simple terms the more rope available to stretch during the fall the lower the impact force on the safety chain. This potential impact force can be measured using the following ratio:

Distance of fall divided by amount of rope out gives us the fall factor. The higher the fall factor the greater the impact force on the safety chain.

(Image on the right taken from the MLT publication Rock Climbing: Essential Skills & Techniques by Libby Peter illustrates this.)

Therefore the Fall Factor is a simple and quick way, without getting hung up on complex physics and maths, of assessing how severe the impact force could be on the belay.

In reality a whole host of factors come into play such as whether the falling climber hits or bounces of ledges, how complex the pitch is (i.e. the rope zig zags), type of rope used etc that affect the actual impact force. It is also worth taking into account that you might have more rope out than you think as often the belayer will have a loop of slack out to prevent the leader being pulled of balance and/or allow a fast clip to be made.

Credits

Many thanks to MLT for kind permission to use the illustration of Fall Factors from their recently revised publication ROCK CLIMBING: Essential Skills & Techniques by Libby Peter.

- You can purchase a copy Direct From MLT

George McEwan is based in Aviemore, Scotland and is a Senior Instructor at Glenmore Lodge (the National Outdoor Training Centre) and is the Technical Officer for the Association of Mountaineering Instructors (AMI).

George has been climbing and mountaineering for over twenty years. In that time he has put up numerous first ascents both in the UK, Europe and Nepal.

He has climbed mostly in the French Alps around Mount Blanc, both summer and winter. Also climbed in New Zealand Alps. Expedition to Langtang Valley, Nepal 1st ascent of the North Ridge North face Naya Kanga 1989. Second British Expedition to Tien Shan for attempt on South Face of Khan Tengri 1993. 1999 trip to Alaska to attempt Nettle - Quirk route on Mt Huntington, then West Ridge of Mt Hunter.

In the past few years his climbing has focussed primarily on waterfall ice climbing, with this passion taking him to Canada, Colorado, France, Italy, Austria and Switzerland.

His professional career has spanned seventeen years during which he has worked for Outward Bound, and for the past thirteen years with Scotland's premier National Outdoor Training Centre - Glenmore Lodge where he currently works as a Senior Instructor.

Although actively involved in all forms of climbing from bouldering through to ice climbing, George's primary passion is steep water ice.

- IMPROVE: Steep Ice Climbing Technique 5 Jan, 2016

- Essential Winter Skills: Ice Axe Self Arrest 5 Mar, 2015

- Ice Climbing Anchor Strength - Analysis 30 Jan, 2012

- Ice Climbing - Physical and Mental Advice 19 Dec, 2011

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Colorado Ice 28 Feb, 2009

- Glenmore Lodge: 60 Years Involvement in Climbing and Mountaineer 9 Oct, 2008

Comments