Throughout history, there have been British women at the forefront of climbing and mountaineering, on both a national and global level. Lucy Walker, Gwen Moffat, Alison Hargreaves — to name but a few. Protagonists in adventure and exploration, who may have been recognised, yet rarely celebrated and all too often overlooked. Dorothy Pilley is one such lady.

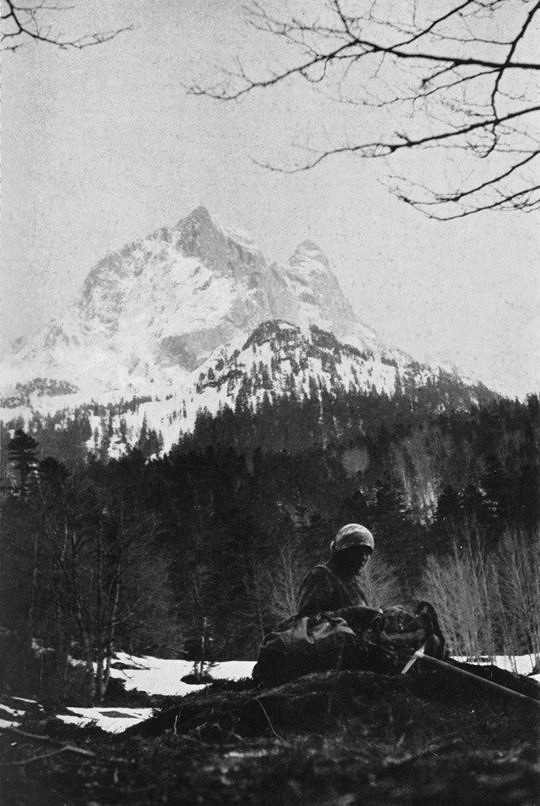

Born in London in 1894, Dorothy's unwillingness to be bound by strict Victorian middle-class social values shone through from an early age. Despite being sent to an exclusive school to be primed for a life of housewifery, she rebelled and took on journalistic work, eventually becoming a secretary for the proto-feminist British Women's Patriotic League. Upon discovering climbing and the outdoors on a trip to Wales at the age of 17, there was no looking back: 'Mountain madness had me now for ever in its grasp.' In thick tweed knickerbockers, she began forging her own path in the British mountains, a youthful exuberance later leading her to the European Alps and beyond.

From first ascents and groundbreaking explorations in Wales - on Tryfan Lliwedd, The Devil's Kitchen and Cwm Idwal - to the Lake District and Skye, Dorothy went on to make ascents of the Charmoz, the Grépon, the Dent du Géant and a traverse of the Drus - all in her first alpine season. She initiated the first guideless party of women on a traverse of the Egginergrat and the Portjengrat, and climbed the Zmutt ridge of the Matterhorn. Alongside her husband and French guide Joseph Georges, Dorothy achieved the second ascent of the North East ridge of the Jungfrau in 1923, the North ridge of the Grivola in 1924 and the coveted first ascent of the North ridge of the Dent Blanche in 1928 - the pinnacle of the couple's climbing careers. Their hunger for the mountains not yet sated, adventures further afield in Japan, China and Canada ensued.

'Her inclination to be a great lady went with an equal and opposite desire to be off with the raggle-taggle gypsies.' - Dr. Richard Luckett, recalling Dorothy

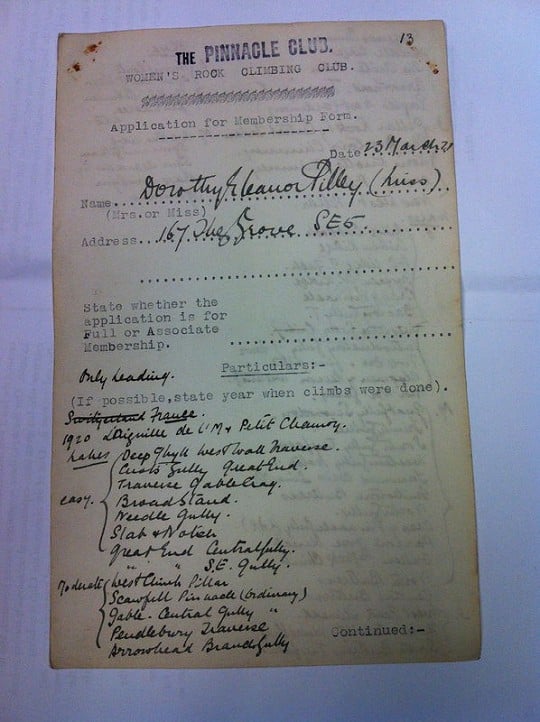

Eschewing society's norms and traditional gender roles, Dorothy's exploits in the hills were anathema to London life. Living in Cambridge with husband Ivor Armstrong Richards - the renowned literary critic, also known as I.A. Richards - academic life did not appeal to Dorothy, the hills and peaks instead taking on 'something of the place that a university may hold for others.' However, her single-minded enthusiasm for the mountains did not prevent Dorothy from contributing to mountaineering culture in a benevolent manner; she was founder, President and Journal Editor of the Pinnacle Club for women from 1921 onwards, a 'tireless recruiting sergeant' for various clubs with a penchant for both sharing stories and listening to the adventures of others in the mountains, until her death in 1986 at the age of 92.

Throughout her life, Dorothy had diligently kept diaries and notes about her and Ivor's climbs and the emotions surrounding her escapades in the hills, enabling her to pull them together in a memoir titled Climbing Days, first published in 1935. 75 years later, in 2010, the memoir was discovered by Dan Richards — Dorothy's great-grand-nephew — who was astonished to discover the amazing life and achievements of this previously unsung and overlooked relative. Curiosity piqued, he set out to explore the world of his pioneering great-great-aunt.

Following in the hand-and-footholds of his great-great aunt, Dan's latest book Climbing Days - fittingly reviving the title of Dorothy's memoir - traces her adventures with a keen and analytical eye and a heavy dose of humour and self-deprecation to boot. An inexperienced climber, Dan threw himself in at the deep end, embarking on a climbing apprenticeship and visiting Dorothy's old haunts, culminating in reaching the same lofty heights as Dorothy and Ivor on the North ridge of the Dent Blanche. Adamant that his book should serve no purpose as a 'flat recapitulation of Dorothy's memoir,' it's clear that Dan has instead created a touching tribute — a tangible 'companion piece' — to his relative, who is surely deserving of more recognition.

In an attempt to find out more about Dan's extraordinary journey and his remarkable great-great-aunt, I sent him some questions which he kindly answered in great detail...

*Dorothy was known as Dorothy in print, but as Dorothea to those who knew her.

'I saw that I had no idea who Dorothea really was. She remained beyond reach, ambiguous, a divided personality, her life split into two distinct acts, the young elemental 'Pilley' who wrote Climbing Days, and the elderly lady who appeared sporadically in my father's childhood, dispensing lethal gifts, amalgamate of I.A.R. I determined to put that right.' - Dan Richards, Climbing Days

What was the catalyst for delving into her book and history?

I found Dorothea's memoir completely by chance whilst looking through my father, Tim's study. I think I must have known about it because I remember that the name and title — also Climbing Days, my book is named after Dorothea's — rang a definite bell.

The contents of my father's studies have always held a fascination for me; the sort of places where one might discover treasure such as a box of antique photographs or tinplate trains, WWII Hurricane pilot boots, or a beautiful book of Gaudi. I recently wrote about an expedition he made in the early 80s to Svalbard from which he returned with a sun-bleached polar bear pelvis he'd found on the Brøgger Peninsula. He's that sort of man. It was that sort of house. So, in one sense, it wasn't unusual to find something of interest but Dorothy's memoir was so vital, so energetic and unique that I knew almost as soon as I'd begun reading it that I wanted to follow up and find out more.

'Perhaps in the mountains I could meet them halfway.' Climbing clearly runs in the family, but how much did you do, or how much interest did you show in it prior to following Dorothy's story?

I'd climbed trees as a child, a few rocks in the Scouts — although I remember that I much preferred abseiling! — but apart from a few indoor climbing and bouldering sessions at university I'd very much lapsed. I knew my father had climbed in his youth but I wasn't aware of how widely and well; this became apparent as I went on.

So, in short, hardly at all! It was a steep learning curve but I knew from the off that I had to physically engage with her life and go to the mountains. I couldn't be vicarious. To be true to Dorothea I'd have to throw myself into the challenge whole-heartedly and climb after her.

'The mountains were her true domain - anathema to London.' You remark on Dorothy and Ivor's 'otherwordly' status in Cambridge as academics who had a hidden adventurous side - something which is especially unusual for a woman of this era. How do you view Dorothy's adventures in the mountains - was it as much a deliberate act of rebellion against Victorian patriarchy, to 'escape a cycle of social expectation' as a it was a pure love for climbing and the outdoors?

I think once she'd discovered the joy of climbing and the savage splendour of the mountains she was set on a life in their midst. The fact that this was anathema to the social conventions and expectations of the time only made her more determined to fight for a wilder existence beyond the stifling confines of her home and city life. In that sense the two things went hand in hand but I think it's important to say that later, once she was financially and socially free to do what she liked, she kept going back to peaks whenever possible. The landscape was absolutely part of her being and character; and Ivor's too. They were otherworldly in that sense — always questing and disappearing into these challenging landscapes unthinkable to many of their peers and many in their families.

''Leaping crevasses in the dark,

that's how to live!' you said.'

- Ivor to Dorothy, from his poem 'Hope' which he wrote as she recovered from a broken hip.

'Climbing Days and 'Hope' painted a very different portrait of the couple from the vague stories I'd been told, growing up.' What differences and surprises did you encounter, and how did it feel personally to unveil a 'hidden' or lesser-known side to your relatives, 90 years later? How did your father and other family members respond to the stories and insights revealed by your research for the book, and the book itself?

The main thing which struck me — the most astonishing thing, perhaps — is how good they were. They were bloody good climbers. Superb athletes and technicians.

I think there's often a temptation to patronise the achievements of people in the past but pursuits such as exploration and climbing challenge and contradict these ideas completely. Mountains haven't changed much in 90, 100 years — they're still the same big beasts. The ice and snow quality and coverage might be inconstant and temperamental but when one stands at the bottom of the north face of the Dent Blanche, as I have, and look up it, as I did… it's astonishing to think that they climbed that in 1928 with Joseph and Antoine; in tweeds; with a hemp rope; with next to no kit and axes more akin to building tools than what we have today.

It's amazing and humbling beyond belief. They were tough people; apparently fearless — I was perplexed that I knew nothing about them growing up!

There's a book of photographs of Ivor climbing on the rooves and steeple of Magdalene College, Cambridge, in 1915. Again, hazardous and exposed beyond sense.

All these electric images, letters, route maps and accounts in archive box files and drawers, untouched and barely known. As soon as I set myself to celebrate Ivor and Dorothea's exploits I knew that I had to get these things into the public domain — reproduce as many as possible in the book because their lives were so vital and extraordinary. They deserved to be shouted about and celebrated.

Of course my father knew about the stories but I think the last time he'd really engaged with the legacy — these terribly dusty deadening words 'legacy' and 'archive' — was over 30 years ago. But, again, he'd set out to engage with Dorothea's climbing feats in a positive, physical, heuristic way — he climbed the Ferpècle Ridge of Dent Blanche… the fact that he never told Dorothea about that is a whole other can of worms!

'They found a symmetry and balance in the privacy of the mountains that many other couples might have kindled in more prosaic settings.' Dorothy's relationship with I.A. Richards appears, as your father describes, to be one of 'devoted companions' bound by a love for the mountains - 'not like any married couple he'd ever known.' Indeed, Dorothy writes of I.A.R. in Climbing Days rather matter-of-factly, devoid of great emotion. Their perceived outward social awkwardness in everyday life contrasts with Dorothy's revelations of 'How intimate is the quality of companionship given by adventure in the hills' and a companion's exclamation "Ah, les amoureux!" with reference to the couple huddled together at a belay. What was your take on this mysterious duality - were they simply an introverted couple who expressed themselves in the outdoors?

I think it boils down to the fact that they were profoundly happy and comfortable around each other. When two people are so close it's all too possible to appear insular or cliquey but I think the great love, trust and joy they experienced in each others' company was a great gift and comfort to them both throughout their long lives.

I hope I'm as lucky to experience such an affinity with another.

I think they completed each other and that's a truly wonderful thing.

'The Alpine Journal wavered between incredulity and stern disapproval, announcing the first woman's lead of the Grépon with a hesitating 'it is reported' and declaring that 'Few ladies, even in these days, are capable of mountaineering unaccompanied.'' - Dorothy, Climbing Days

'It had been a long conspiracy prompted by the feeling we many of us shared that a rock climbing club for women by women would give us a better chance of climbing independently of men, both as to leadership and general mountaineering.' Dorothy's pivotal role in founding the Pinnacle Club and her commitment to the cause was widely appreciated: 'Despite her busy life and many commitments, she had attended almost all Pinnacle meets, and her prestige as a climber, writer and speaker could only add to that of the club,' writes Shirley Angell in Pinnacle Club: A History of Women Climbing. Whilst relaxing with companions in the Pyrenees, Dorothy writes that they 'discussed sardines and Feminism' before describing at length the multiple ways of consuming sardines and ending with 'The Feminist argument, which was linked to the sardines, is less easily summarized.' Dorothy doesn't write extensively on the topic, nor does she present a feminist agenda as such. One pragmatic comment stands out, as she is warned by a male guide that a glacier would be unfit for a lady due to cornices: 'Why feminine feet should disturb them more than masculine weight it was hard to guess.' What was your impression of her views on women's mountaineering?

I love the story of that sardine and feminism symposium!

I think Dorothea wore her feminist credentials proudly and boldly. The fact there isn't a great deal explicitly written about feminism or an emancipatory agenda in her memoir seems to me to miss the point — she was living it. Dorothea is an exemplary feminist role model — that fact she lived as she lived, would not be put down or told what she could do, how she was to be… the fact she helped found the Pinnacle Club, the fact she pushed a transformative, emboldening, egalitarian agenda whenever she was in a position to do so speaks for itself.

I don't think she felt that male institutions ought to be brought down or fundamentally reformed, I think her impulse was always to bypass them entirely and forge ahead anew. She was a pioneer; the personification of action and collected and inspired a cohort of similarly minded strong women as she went.

She didn't hang about waiting for things to change in London, she led the changes in the mountains. She embodied the revolution she wanted to happen in the climbing world and beyond.

'The sense of continuity was extraordinarily restful. Most Alpine travellers find themselves drawn to the mountains by a twofold pull - the impulse to go over new country and to revisit familiar scenes.' In some ways your journey matched this description from Dorothy - revisiting the haunts of your ancestors which were mostly new to you, but which also held a familiarity through your research. Your journey took you to Scotland, North Wales, the Lake District and the European Alps. Which places along your journey strike you as particularly memorable, perhaps where you felt the strongest connection to Dorothy or 'that feeling of perpetuity' of which she writes?

The welcome and hospitality my father and I received in Switzerland once the local people discovered our name and lineage was amazing and very moving. We'd just walked down from Rossier after an ignominious benighting on the side of the Dent Blanche; we'd been awake a good 48 hours and were knackered; and they opened a hotel, fed us, phoned around the local Swiss Guides who turned up to buy us a drink, shake our hands, and tell us that they were honoured but that we were terrible fools for climbing the mountain in late September in such snow… it was one of the best, most poignant things that's ever happened to me — because they were all there because of Ivor and Dorothea. In that moment they were both alive in the room there in that gîte above Les Haudères.

Throughout the writing and climbing of my book I grew to know Ivor and Dorothea well — as well as I could know two people who died before I was a toddler. I grew to know them in increments, through moments of discovery, insight and clarity. For example, halfway through the project I discovered a tape of Dorothea speaking: that changed the way I thought about her; her voice was very unique and instructive… so moments like that altered and coloured things but that week — and really I mean that night — in Switzerland the whole thing came truly alive. I climbed up to Bertol from Arolla with my father, then over the glaciers round to Dent Blanche, then up it before sitting out the night on a ledge in a light blizzard opposite the Matterhorn, and then we walked down, got a thorough telling-off from the hut guardian and then stumped and stumbled down down down to Ferpècle… and then on on on to La Sage where we encountered that — that welcome, that warmth. It was life-changing. Astonishing. Damascene.

And then there were our meetings with André Georges, great nephew of Joseph — Dorothea and Ivor's guide. That was astonishing. André is an phenomenal guide and climber, a gentle giant; a Swiss legend. He's climbed nine of the fourteen 8,000 metres mountains in the world. His achievements are breathtaking. He's been up Everest without oxygen 'for the sport' — and he'll tell you these stories in his deep soft voice with an artless nonchalance as if it's the most normal thing in the world.

To make contact and reestablish links with a man like that; to hear him talk with such love for Dorothea and Ivor, to know he held them in such high regard, and to reunite the Georges and Richards families after a gap of so many years was wonderful.

'Something in the fall of the slopes, or the grasp of the vegetation, the tint of the rocks, the tension of the summit-lines, would tell me - though what exactly it was might beat all efforts at analysis. Can a lover explain just what is different from all others in his beloved?' - Dorothy on mountains, Climbing Days

There is much philosophical discussion about why people climb in your book - 'as an effort to avoid the question of why they do it.' Dorothy writes about climbing on Skye; 'Risk was the salt, but he or she would be a stupid cook who thought the more there is of it the better!' and ends her memoir with the admission that mountaineering is at times a 'toss-penny game.' You write of the 'beyond' and the climbers who do and do not push themselves into this realm of discomfort or danger. Did you come to a greater understand of the motivations for mountaineering, not only through Dorothy and Ivor, but through all of the present day climbers you met?

I think there's great truth in the idea that people climb to avoid the question because the physical and mental clarity of climbing is wonderful. I mean, I'm not sure the question of why occurs to somebody engaged in the joyous sport of it any more than it would to a racing car driver or a marathon runner. All these things might seem dangerous, involved or exhausting to one spectating and speculating from without but that's to miss the point, surely. All these pursuits — and climbing particularly — seem to me to be as much, if not more, about the inner than outer life… one can do, see, sense, feel and be things in the mountains that one just can't elsewhere.

Your father, Tim, climbed the Ferpècle Ridge of the Dent Blanche in 1981 - Dorothy and Ivor's most celebrated first ascent, which inspired Tim to start climbing - in an attempt to engage with his relatives, 'the conversational approach having foundered.' However, Dorothy never heard of his climb. Was your desire to summit a continuation of this, as a way of understanding their achievement, or as a sort of family 'tradition'?

Yes. It's a tragic loss which we both feel keenly. He had the opportunity to engage and befriend this amazing lady on her own terms — he'd made a pilgrimage, done all the hard work, but something held him back; some debilitating social or familial lack of confidence… it seemed such a waste and so British somehow. That buttoned-up self-sabotage — he climbed the Ferpècle Ridge to connect with her legacy in the most amazing way and her, she specifically… then he kept it to himself. It boggles me. I find it so tragic and truly sad; because now, having got to know her a little in retrospect, I know that she would have been thrilled.

Dorothea was not an unfeeling or frosty woman. Any appearance to the contrary was just generational reserve, I think — she would have been thrilled with Tim's endeavour and gumption. She would have embraced him totally and they could have become friends, made up for lost time.

But it didn't happen and I don't know if Dorothea ever found out about his exceptional act

In that respect my book is a gift to my father; an attempt to make right that wrong from 30 years ago.

'The strangeness of the dual life made, in those days, a cleft, a division in my mind that I struggled in vain to build some bridge across. Kind, firm friends would say 'All good things come to an end', or 'You can't expect all life to be a holiday.' But to me, and to climbers before and after me, this was no question of holidays. It went down to the very form and fabric of myself.' - Dorothy, Climbing Days

Dorothea appeared to be a very modest woman - as Editor and President of the Pinnacle Club she often neglected to write about her own climbs in journals: 'Dorothea Pilley was Editor and did not mention her own achievements' - A History of Women Climbing. What do you think Dorothea would make of her great-great nephew's journey to retrace her life and write a book about her memoirs?

I think she would have been pleased. She was, as you say, quite humble about her achievements but she loved good climbing talk, tall tales and fun — and there's plenty of that in my book. She was an inspirational lady and I think she'd have been delighted that her writing and climbing is still known and still inspiriting others to follow in her footsteps.

Finally - will you keep up your walking and climbing? Has Dorothea inspired you to take your experiences further? What's next?

I've just finished the proposal for my next book, tentatively titled Outpost, which will investigate unique cabins — bivouacs, fire-watching lookouts, lighthouses, huts, shelters around the world — using those structures as prisms through which to examine ideas of human exploration, isolation and wilderness.

I plan to explore such buildings as the bothies of Rannoch Moor and the Cairngorms, sheds in Svalbard, Inca tambos in Peru, sæluhús lodges of Iceland, and Captain Scott's Terra Nova Hut, Cape Evans, Antarctica. Each structure will form the focal point for a chapter in the book, the centre of a story in an ongoing narrative.

I went to Iceland to begin writing in June and I'm off to the Cairngorms in a few weeks to carry on and I intend to do a bit of climbing with my friend Steve whilst I'm there.

If one of the questions at the heart of Climbing Days was 'why climb mountains?' the new book will seek answers to the questions of what draws people to wilderness and the outposts within them. What can such places tell us about the human condition? What compels us the ends of the earth, and what future do such places have?

- INTERVIEW: British Mountaineering Council CEO Paul Ratcliffe reflects on 2024 12 Feb

- INTERVIEW: Team GB Olympian Erin McNeice on her breakout 2024 season 11 Feb

- SKILLS: Push Your Grade: How to Climb Your First 7a Sport Route 6 Nov, 2024

- ARTICLE: Olympic Route Setter Garrett Gregor on Paris 2024 17 Sep, 2024

- ARTICLE: How did the Paris 2024 Olympic Games impact Sport Climbing Athletes' Instagram Followin 4 Sep, 2024

- ARTICLE: Meet the Paris 2024 Olympic Routesetters Part 3: Olga Niemiec, Boulder 4 Aug, 2024

- INTERVIEW: Meet the Paris 2024 Olympic Routesetters Part 2 - Martin Hammerer, Lead 1 Aug, 2024

- ARTICLE: Sport Climbing at Paris 2024: Schedule and How to Watch 30 Jul, 2024

- INTERVIEW: Meet the Paris 2024 Olympic Routesetting Team - Garrett Gregor 29 Jul, 2024

- INTERVIEW: GB Climbing Olympic Coach Rachel Carr on Paris 2024 24 Jul, 2024

Comments