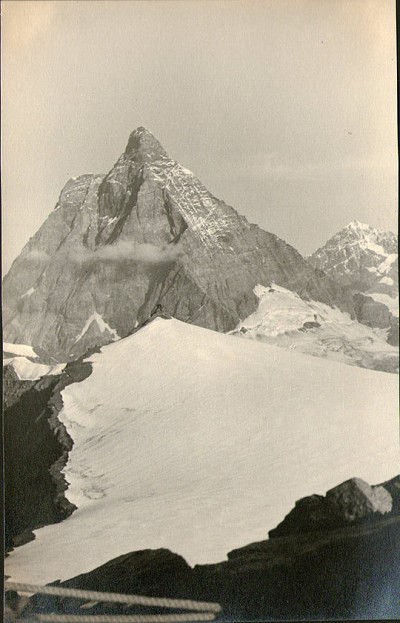

In this article, Howard Ernest Hasseldine describes an ascent of the Matterhorn via the Hornli Ridge in 1937. As was typical of the day, Howard was guided to the summit by local guides. The account gives a fascinating view into the climbing techniques used at the time and the article is comprised of Howard's diary from the climb, accompanied by photos he took along the way.

Prologue

Many people, who have never climbed a mountain, misapprehend the motives inherent in mountaineering; there are some who even imagine that the attainment of the summit and the view there from is the raison d'etre of the craft. The summit is not a reward in itself; it is a fitting culmination of endeavour. The true mountaineer does not tread it in any spirit of vain gloriousness; he experiences nothing but a quiet satisfaction that the difficulties besetting his upward path have been surmounted. He will not yell and scream with unseemly triumph; he will respect that which has given him joy, and be humbled by the prospect before his eyes.

This piece was probably written by HEH, but unsure. (Found typed up amongst his papers of his account of his climb of the Matterhorn, which were handwritten.) The piece was then edited by Howard's daughter, Liz Webb in 2011.

The Lower Slopes

In spite of good weather conditions during the last two days, our guide, Johann Zummermatter, had not been anxious to attempt the Matterhorn. "With the wind in the wrong quarter the weather might break at any moment," he explained. So we had restricted our activities to the Furggen Ridge, which gave a greater margin of safety in the event of a sudden storm.

However, shortly after breakfast, on the morning after our return from the Furggen, Johann arrived in the best of spirits, confident that the weather would hold for at least twenty-four hours. His suggestion that we should set out for the Hornli Hut after lunch was enthusiastically received. At last we were to have a crack at the Matterhorn!

The next two hours were spent looking over equipment and making arrangements for the provisions we should need to take with us. These details having been settled, we went out into Zermatt village for a stroll before lunch. Imagine our surprise to find cameramen 'shooting' a film scene outside the Monte Rosa Hotel. The explanation was that London Film Productions were shooting the final scenes for their dramatic climbing picture "The Challenge", which tells the epic story of the first ascent of the Matterhorn by Edward Whymper, in 1865. The occasion seemed an appropriate one indeed, as we were ourselves on the threshold of the same adventure, and we experienced a certain pride that we were about to follow the route pioneered by that great Victorian Alpinist.

Leaving Zermatt after lunch, we began the pleasant slog up to the hut on the Hornli Ridge, from which the ascent from the Swiss side is usually made. A more pleasant afternoon tramp cannot be imagined. At first we passed over flower-strewn Alps, where cowbells made merry music: then, as higher ground was reached, the path wound through cool pine woods, and was carried over foaming torrents by crazy little wooden bridges which bent as we crossed them.

Arriving at the mountain hotel at Schwarzee at about tea time, the opportunity for refreshment was not to be missed, and we spent a lazy half hour sipping tea on the terrace, while speculations were made regarding the condition of the mountain. It was recalled that before the present fine spell, snow had fallen heavily on all the big peaks, so that the rocks were still likely to be iced at high altitudes.

During tea a diminutive black and white cat settled itself on my knees and refused to be moved. This little animal, we were assured, had once followed a party of climbers to the summit of the Matterhorn; during the descent the climbers missed the cat and assumed some harm had befallen him. After an absence of four days, however, the adventurer returned in a semi-starving condition but otherwise none the worse for his climbing feat.

'Base Camp'

Another hour saw us at the Hornli Hut, situated on the Hornli Ridge at about 10,000ft and almost within a stone's throw of the base of the Matterhorn. This position commanded a grand panorama of peaks and glaciers. In view of the perfect weather conditions we were not surprised to find the hut already full to capacity. However, at the Belvedere (a small mountain hotel close by), we were offered an attic bedroom containing three small double beds at a cost of 3 francs per head. This seemed reasonable enough, and we had the added advantage of sharing a large 'dining room' and the use of a good cooking stove. The walls of the 'dining room' were hung with highly coloured views and musty photographs, and the window was draped with heavy lace curtains, giving to the room the air of a mid-Victorian apartment. All this seemed strangely out of place on the Hornli Ridge! And yet it was also a link with the Victorian pioneers.

After supper Sedge and I strolled out onto the terrace for a breather before turning in. Outside it was beautiful. Night had long since possessed the valleys; it was calm and intensely dark. A cold alabaster-like afterglow lingered on the peaks. The clouds had dissolved and the stars shone out like the fires of an army encamped on the plains of space. Down in the valley, some 5000ft below, the lights of Zermatt twinkled bravely, vying with the great stellar constellations. Beyond the Furgg Glacier the outlines of the great snow peaks were faintly discernible – Monte Rosa, the Lyskamm, the Breithorn – and nearer at hand the Matterhorn towered up into the darkness.

As our eyes became accustomed to the dark a point of light became visible, moving slowly along the Furggen Ridge. It seemed a late hour indeed for anyone to indulge in Alpine ridge walking, and we began to wonder whether it was a rescue party going to the aid of some injured climber. By some means unknown to ordinary mortals, the Swiss guides always managed to have information about the movements of all climbing parties operating on the big peaks within a day's march. Johann, who by now had joined us on the terrace, proved no exception, and readily explained that the party consisted of two ladies with their respective guides. This party had left the Belvedere at 3 o'clock that morning, intending to traverse the Matterhorn via the Hornli Ridge and the Italian Ridge, and to return to the Belvedere the same evening. It seemed they had now decided to by-pass the Belvedere and to descend as far as the Schwarzee Hotel that night. While we watched the tiny point of light which we knew was the lantern of their leading guide, the climbers descended from the ridge and started the long trek across the Furgg Glacier. As we turned in, about 10 p.m, Johann expressed an opinion which we all shared. "Those ladies, they are tough," he said. We went to bed with a sense of well-being, and although the bedclothes felt decidedly 'clammy' to the touch, we cared little for this. As for myself, I clambered into bed attired in climbing breeches and a sweater and almost immediately fell into a sound sleep.

The Ascent

At 2.30 a.m we were roused by a loud bang on the door. Grudgingly creeping from our beds, we pulled on our climbing kit and boots and went down for a hurried breakfast, eaten by gaslight. By 4 a.m. we are roping up in the hall – first, Johann, Lilian and David, second, Sedge and I and then Leo, Mason and Monty. It is a romantic business this launching out into the darkness by lantern light. You start out frowsy and yawning. Your stomach complains bitterly at having to consume a meal in the small hours, and even the stars seem heavy-eyed and uncaring. A thousand malicious stones lie in wait to trip you and, as you stumble about, you think how foolish mountaineering is and what a mistake you made in leaving your bed. But presently the blood is quickened by exercise, and in some subtle and mysterious fashion you begin to enjoy yourself. We found we were not the first in the field. Several parties had already left before us, and in the darkness we saw the lights of their lanterns several hundred feet up the ridge above us.

A few minutes' walking over a stony track brought us to the foot of the mountain, which seemed to rise abruptly in a towering, rocky mass. The modest aide of light made by our candle-lantern seemed only to intensify the surrounding darkness. The first pitch consisted of a scramble up an easy gully leading to a narrow ledge. The traversing of this ledge presented no difficulties until a corner was reached and the ledge narrowed slightly. At this point a bulge in the rock face tended to push the climber outwards and the darkness below did not add to his feeling of security.

The next half an hour was occupied with ascending a series of easy rock faces and gullies, and I found my electric pocket torch of great value in revealing elusive hand holds. Frequently it was necessary to hold the torch between my teeth, so as to leave both hands free. The night was warm and clear, the stars shone brightly, and we were now getting well out on the ridge. We had so far had no trouble from falling stones – probably the climber's chief source of danger on this mountain.

The Matterhorn is an isolated peak; its sides are almost uniformly steep, and it is naturally exposed to every kind of severe weather. It is said that the mountain 'manufactures its own weather', which very often bears no relation to the conditions prevailing in the nearby valleys or on the surrounding peaks. Violent electrical storms, accompanied by heavy falls of snow may occur at any hour or at any time of the year. These are the forces that split/shatter the rocks, and cover the steep mountain sides with loose stones, insecure rocks and debris, so that there are almost continuous falls of stones and avalanches. Part of the etiquette of a climber is to avoid disturbing loose matter of this kind, which might endanger other parties on the mountain. Some of the lower gullies act as funnels for these rock falls and are therefore extremely dangerous for climbers. The guides are of course fully aware of these dangers and follow a recognised route, which has been found to be less subject to avalanches and falls of rock.

By 4.30 a.m the stars had now begun to fade and on the eastern horizon appeared a band of pale primrose yellow, silhouetting the dark outlines of the peaks of Breithom and the Lyskamm. Our lantern was extinguished and placed in a niche of rock, to be collected on the descent. As the sky gradually became suffused with the growing light, so the great ranges of snow-covered peaks began to assume an alabaster-like whiteness. To watch the coming of dawn among the snow peaks is an experience that long remains in the memory. One's inclination is to stop and watch the wonderful transformation that is going on all around. The summit of the Matterhorn, towering above, became a haze of golden light.

So far the atmosphere was brilliantly clear. Now a wispy cloud rose from a snow field several thousand feet below and glided up the mountain side, lingering around the summit. At about 7 a.m. we arrived at the Solvay Hut, a refuge for benighted climbers. It was made from stout timber lashed to the rock by wire hawsers and was always left open. It contained a table, chairs, bunks and blankets. Ravens were flying around the wall of rock below the hut, at about 13,000ft. We sat on a ledge of rock outside and ate apples and cheese. Immediately above the Hut was a series of long rock pitches so we got another 50ft of rope out. We had now deviated well to the left of the ridge and the summit loomed up, a massive shoulder of rock capped with frozen snow.

"How long to the summit now?" – We asked the guides. "About two more hours," was their answer. Now we were confronted with patches of frozen snow and glazed rocks on the slopes leading up to the shoulder. A shoulder is a massive bulge of rock, glazed with ice. Pitons were driven into the rock and ropes fixed; one foot was placed each side and then we hauled ourselves up. A series of ropes lead us over the shoulder and up onto summit ridge. Pitons were used as belays. We were held up here by a Swiss gentleman with two guides. He had apparently only recently come out of hospital where he had been since December with leg trouble!

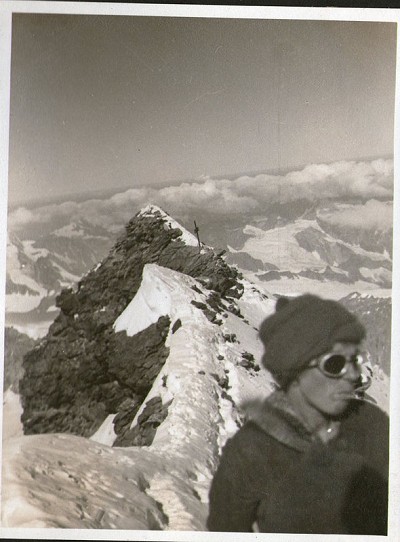

About 9 a.m, above the shoulder, short steep ice slopes lead us right onto the summit, which was a narrow snow ridge about 50ft long. We had indeed made it! One end of the ridge was slightly lower, called the Italian summit, on which was a cross of iron 10ft high. On one side of the ridge, steep snow slopes bulged away into space. The other side was hidden by an overhanging cornice of frozen snow. The Guides shook hands with the climbers.

Floating some thousand feet below was a fleecy layer of rolling white clouds which obscured many of the surrounding mountains, but the higher summits protruded through the clouds. Westward, the range including Mt Blanc; eastwards in Bernese Oberland – Jungfran, Eiger, Monch and Finsterarhorn. The sky was a vivid blue and the sun shone brilliantly but the temperature was well below freezing point. We ate a hurried snack, keeping mitts on, whilst admiring the view; however it was too cold to stay more than 10 minutes or so. The guides were anxious to start the descent so we followed their advice and began the long climb back to Zermatt, feeling exhilarated and glad to be alive.

In loving memory of Freda Burrant, who passed into fuller life from the Matterhorn at dawn August 6th 1936, aged 24 years.

(These words were found hand written by HEH on the small piece of paper on which he had written his account of the actual climb to the summit. As she did not appear to be in his climbing party I assume he had heard of her death just before their ascent.)

Comments