A veteran of 45 expeditions to the high mountains of Asia, Doug Scott is one of Britain’s greatest high altitude mountaineers. He has reached the highest peaks on all seven continents – ‘the seven summits’ – and was part of the first team to climb Everest’s treacherous South West Face. In this extract from his new autobiography Up and About: The hard road to Everest, Doug sets out to explore the Tibesti Mountains of Chad after two months spent crossing the Sahara.

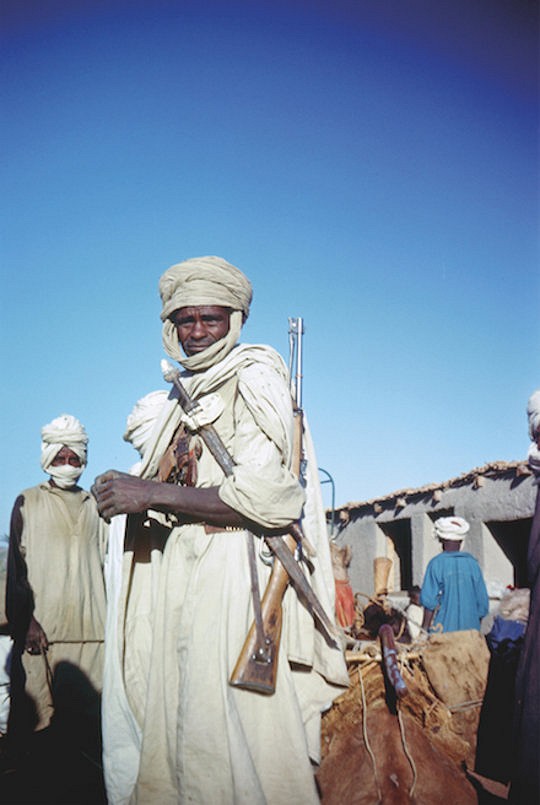

We soon adapted to our new environment, sitting for hours bartering for a woven reed bowl with an old woman wearing crude, leather sandals, a black smock, a ring in her nose and a colourful scarf, gypsy fashion, around her plaited hair that glistened with goat fat. Pete played his mouth organ while Clive began sketching the Tibbu by the white light of the pressure lamp. The young men had brought their wives along and they collapsed in hysterics at the drawings. The men broke into excited chatter when we showed them photographs of Thesiger’s Arabs from Arabia, pointing out the differences in apparel and their camels – and the rolling dunes that were absent from Tibesti.

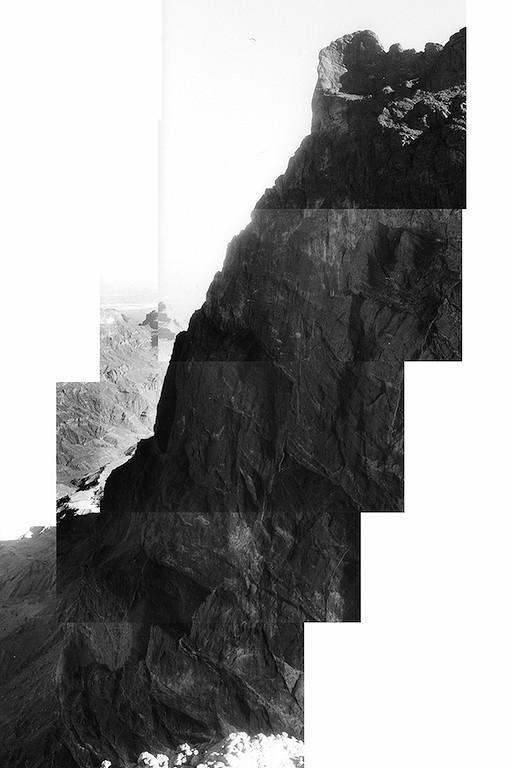

Time passed all too quickly in Modra, and we needed to focus on Tieroko. On the drive round we had seen it from every side but at a distance it was little more than a silhouette. Our French maps did not explain the complicated gorges that carved up the region. A sketch from the first Cambridge expedition in 1957 helped fill in the picture. They narrowly failed on Tieroko but climbed other peaks in the vicinity. Tieroko, at 2,910 metres, is actually the highest point on the south side of another eroded crater rim. The area is particularly isolated, barren and difficult to traverse. Torrential downpours that occasionally drench the mountains cause the temporary streams to eat deep into the soft volcanic rocks. They have cut the mountains into serrated ridges and crazy pinnacles that make route finding a formidable problem. Yet the main problem was maintaining adequate water supplies. In the whole of our journey in North Africa we only saw running water at Modra and the only water in the mountains comes from rock pools known as guelta.

We left Modra with two heavily laden donkeys and Coke [local guide] whom we hoped would point out the waterholes. Walking over ten miles of boulder-strewn country, we then crossed dry valleys draining the south side of Tieroko’s crater, eventually coming to the wadi that drained Tieroko itself. We slept the night by some stone circles and Coke returned home after indicating that water could be found at the bottom of the wadi. We climbed down and then back up towards the west ridge of Tieroko, carrying the maximum amount of water we could manage, two gallons each, which weighed in itself twenty pounds. With all our climbing gear and food, our sacks weighed fifty pounds. To reach the ridge, we crossed rough slabs to a dyke of softer rock that provided a line of weakness. It was five very tired, red-faced ramblers who settled down for the night. According to my diary, we cooked our thirtieth stew of the expedition and watched the fabulous sunset.

Perhaps because of the altitude, we did not sleep well and were up early, shivering in the cold of morning. I had read that snow falls in the Tibesti at this time of year on the rare occasions there is precipitation. Now I believed it. After coffee and porridge, we explored the western side of the peak to find a route on to the final summit cone but our search was in vain and we were forced to climb back up 4,000 feet to our bivouac. Running short of water, we turned down the west ridge to Paradise Wadi – so named for the trees around some murky, stagnant pools. Very tired, we slung off our packs and soon had a roaring fire, feasting on corned beef hash and settling in for a better night’s sleep by the glowing embers.

Food was now the issue, so we rose early for another attempt to find a way on to the upper section of Tieroko, following the gorge, sometimes on the left bank, sometimes on the right, around deep pools on the wadi floor. We saw wild Barbary sheep, powerful beasts with magnificent horns and capable of gigantic leaps but still able to maintain their balance on the most crumbly rock. Finally, having turned up a right branch of the wadi’s gorge, we came to a pool that proved to be one of the highest in all the Tibesti, from which we based our final attempt.

A peak overlooking the pool gave us a good view of Tieroko and then we settled in by a fire of acacia wood, singing songs late into the night in honour of St Patrick’s Day. With the last of the porridge gone, we left our gear behind and, taking only water, headed back to Modra in six hours to begin a marathon pancake session. We spent the next few days in the village to rest, and then returned to our camp by the high pool, leaving Mick behind to continue our geographical work. The next day we reached a shoulder on the north-west side where, to our delight, there seemed a reasonable route to the steep summit cone of Tieroko. Ray and I went up to have a look at the route while Pete and Clive went down for more gear and water, as we thought the steep rock above might involve considerable pegging.

When we got to the west ridge and traversed 400 feet towards the south-west ridge, we found a shallow gully of smooth, weathered rock that we felt could be the key to the summit. The couloir gave us 150 feet of interesting, delicate climbing at about Very Severe standard that we protected with two pegs we had with us. From its top we gained access to a brèche from where we could look down the north side of the mountain.

From below we heard our two ‘coolies’ shouting up at us; we spotted them sitting among the rocks surrounded by a pile of equipment and cans of water they had just lugged up from below. They told us we were nearly at the top. After 250 feet of more Very Severe climbing and then some easy scrambling we were, much to our amazement, both sitting on the summit of Tieroko. We hadn’t even brought a camera and there was now enough gear at the bottom to climb the north face of the Cima Grande. I have to admit that although ours was the first human ascent, we found wild-sheep droppings on the summit. We built a cairn and then abseiled down to the brèche and to the shoulder below it. Soon I was back at camp reading James Bond and drinking a brew.

Up and About: The hard road to Everest is available to buy as a hardback from Vertebrate Publishing, priced £24 (free UK mainland delivery). Click HERE to order a copy.

Text and images published with permission from Vertebrate Publishing and not to be reproduced without permission of the publisher.

- GEAR NEWS: 30% off climbing books and guides 18 Nov, 2024

- GEAR: Looking for new climbing venues to explore this summer? 12 Aug, 2024

- GEAR NEWS: The Science of Climbing Training 10 Mar, 2023

- GEAR NEWS: Vertebrate Publishing's Big Summer Sale 29 Jul, 2022

- GEAR NEWS: 40% off Walking books at guidebooks at Vertebrate Publishing 23 Jun, 2022

- GEAR NEWS: The Vertebrate Big Climbing Books Sale 27 May, 2022

- GEAR NEWS: Pre-order now: The Beaches of Wales 31 Jul, 2020

- GEAR NEWS: The Climbing Bible - Technical, physical and mental training for rock climbing 23 Jul, 2020

- GEAR NEWS: Never Leave the Dog Behind: Our love of dogs and mountains 7 Apr, 2020

- GEAR NEWS: Ten ways to keep yourself entertained if you're self-isolating 18 Mar, 2020