25 years later, Australian climber Andy Lindblade reflects on his first ascent of Thalay Sagar's north face, which he achieved alongside the late Athol Whimp, New Zealand's most accomplished mountaineer and the country's first recipient of the Piolet d'Or award.

The first time I laid eyes on the north face of Thalay Sagar, the colour of the sky in the photo, seemingly torn hurriedly from a magazine, was that blue that is almost black; the version of blue that is almost indiscernible from what you imagine the colour of the final minutes of twilight to be.

The ice in the runnels gave off a luminous vibration, snow had been pushed into pockets on the edge of granite and shale protrusions by long-gone pulses of wind. It appeared so still, like the earth stopped moving. I could sense its steepness, leaning into me, reaching to see if I would retract. And the hand that held this photo was Athol's, climbing chalk pushed into its creases, scraped and worn from the struggles of that day and also many other days like it in years past.

We stood at the back of my old Volvo on the sand track under the Bundaleer cliff, our ropes and a mess of a rack laid over our packs which slumped against a fallen branch. The momentum of climbing pitch after pitch up and through the ramparts of that ancient crag all day led us to a state of mind that was keen for more. A week prior we were on the Sheila Face of Mt. Cook, moving fast and light, imagining what this feeling could be like in the Himalaya. We didn't want to think it was a contradiction in terms. Athol had seen this photo and he marvelled at it, talking through the north face's obvious line that had never been climbed directly through its centre to the summit. The photo lay on the sandy warm ground as we cooked dinner, looking at us. We knew we were going.

At the broken edge of Kedar Tal where we situated our base camp, you can lay eyes on all of the north face, but its top first shows itself from much lower in the valley, a couple of days' walk up from the road's end village, Gangotri. We arrived here in the evening, the smell of dinner in the air, ochre flames heating food in dark rooms by the roadside.

Falling asleep, there was that unmistakable rush of sound echoing that is water relentlessly and powerfully moving downhill and being a river, fed by the glaciers and the mountains we were headed up and into at dawn. Listening to that river, the Bhagirathi, Athol told me a story about a goat herder he met while on patrol in the empty expanses of Oman. The old herder slept on a spread of loose rocks to keep himself from sleeping soundly lest someone try to steal his goats under the cover of darkness. Respect, I thought.

The infinitely deep cold never left Thalay Sagar that year, 1996. Our push up the steepening weaknesses on the right of the face did not go far, the rapids of spindrift all over us constantly. We held the hastily built anchor and wrestled with the cold before rappelling, the storm-shaped air moving up from the shaded cliffs below. A few days later in base camp, Kitty Calhoun and Jay Smith told us about their attempt up the central couloir (Kitty had first imagined and attempted this line with Andy Selters in 1986, an inspiration ahead of its time). It was the line to get, the shadowed line, the line that kept rising until it shattered out across an even steeper stack of shale, broken pieces in your hands; the line that was still unyielding to the iron will of the climber. We went back to the base of the wall to recover some gear, but it was gone, avalanched.

Less than a year later we were back, landed in Delhi (with disbelief we watched one of the 747's jet engines catch fire as we descended into the airport – a screaming, screeching meteor attached to a wing). Our trips to the Indian Mountaineering Foundation to secure our permit resulted in a lot of cups of chai and waiting, the thick humid air filling the corridors. Athol's girlfriend Patricia was with us and with permit and paperwork in hand they went ahead in the van to start organising porters in Gangotri. In the meantime, I waited and worked to get our equipment out of customs. Several long days later I laid it all out on the lawn to check it over as Delhi hummed in the background, cold beer my reward. Then, cornered in a lurching bus nursing several kit bags, half asleep, the sweat rolling down my back. At 11 p.m. the bus arrived in Uttarkashi, and at dawn with growing impatience I jumped a 4WD ride up to the end of the road, Gangotri.

That central line looked in fine form. We crested up and onto the small plateau beneath the face, gasping. It was like we'd never left, remembering details, like how long it took to walk from base camp to the end of the moraine to the plateau, and how that time lessened over time. I was about to turn 26, my youthful exuberance crossing over into dedicated seriousness, the willingness to deal with uncertainty.

At night on that frozen plateau I could hear my heart pulsing in my ears, with almost weightless ice crystals settling on my face. Patricia, Athol and I passed the time seeing who could get the lowest pulse rate, Patricia being the officiating authority given she was the doctor! I thought about where I was, and what I was doing, always looking up at what was to be climbed. And now in this moment it was about to be this north face with my best friend, the one who I actually thought could keep going forever, his calm, rugged proficiency shaped by the decisiveness and action that comes from living a dangerous life.

The weather turned some as dawn opened up the darkness, blackened cloud forms tumbling in and then into the face. We scurried down, through the snow building upon the glacial rocks. Waiting in base camp, our liaison officer Rajvinder was upset: "Lady Diana has died!" she said, a shortwave radio in her hand, parts of her voice interrupted by the wind. As we took our packs off falling snow swirled up and down, looking for places to land. Bell, our cook, pulled back the canvas door of the kitchen tent, boiling water ready, that warm rush of the kerosene stove, the soft edges of chapatis charring on an iron pan.

The lower section of the north face is an expanse of steepening ice fields (for us, soft snow was layered over hard ice, with rolling crests of granite occasionally pushing out to reveal what was underneath everywhere) that draws you up and towards that big central couloir. Here in the shadows, where the ice fields meet the rock, the light turns blue, ricocheting off the yellow walls and back into your face.

What sounded like it was going to hit me suddenly did, the ice slicing my face, blood finding my lips shortly after. Here at the top of the icefields and on my front points, out of breath, I stood in extremis, my eyes instinctively scanning to at least get the first piece of an anchor in. A narrow fissure reached away from me, but enough to take a small cam at a stretch. Time inched forward as I worked another piece in. Life wasn't meant to be easy - or fair, apparently. I rigged the haul line for our portaledge and started work, bringing Athol up at the same time. He soon rose up and went through to my left, angling higher in an arc, the ropes setting down then lifting with his movements. Long minutes passed, all my muscles retracting, looking for warmth. I cast the haul bag and ledge off to fall in line with Athol up higher, rolling and scuffing its way through the wallscape.

Together, higher up, the ice ran us into a narrower course, the shapes of the walls changing, cutting deeper, myriad channels where the spindrift from far above would eventually find itself, and us. The falling intermittent masses of snow wrapped around us and the half-deployed portaledge required us to move around awkwardly, the struggle suddenly becoming very urgent. Neuromuscular coordination slowed, yet the situation meant we had to keep working to get the 'ledge assembled, the stress causing our minds to stretch to what was possible. Certainly there was no other option. Much later in the dark, a claustrophobic panic unravelled inside me and my unlikely position in a sleeping bag inside the 'ledge on this north face, the spindrift shaking the portaledge for hours and pushing sleep away.

After this, dawn gave us threatening rolling clouds smashing the upper mountain and then the ceaseless spindrift that arrived in waves. Now Athol is in my memory crunched inward, hanging on both tools, the torrent of falling snow draining the warmth from his arms. Back then I was simply watching for his next move – the man who knew how to keep going. His rugged proficiency battered and weakened through these arduous hours on the face, working up a microcosm of ice up a valley in the Garhwal Himalaya.

A long time later I made out a scream of relief and the ropes went still before becoming taught. I left the belay and then the clouds came in even closer, the rope seeming to evaporate in the grey mist as it wrapped the faintly rounded arête before being drawn out and up by the steeper ice. My mind was travelling through a mental landscape of extremes, from the mountain overrunning my defences to seeing the possibility of it all. Then there was Athol in my view, with his back pushed up against the immensity of the granite, the rope to me from his hands, the two of us right there together.

Here we spent the night anchored to two ice screws, again the moving ribbons of spindrift incessantly trying to push us down. With anxiety we kept trying to melt ice for soup and noodles, the steam so warm but within moments becoming frozen in front of our eyes. Eventually, daylight uncovered the peaks out in front of us, their faint outlines becoming full of shape and density. And within what felt like a minute passing, we prepared ourselves and exited the 'ledge. Two steep ice pitches above and the couloir had run its course. As it ends and shatters outward, so do its granite surroundings, gradually yielding to the "notorious shale band," a deep fortress of multi-dimensional rock indifferent to human form and the point of conversation amongst the alpinists who have stared at the face.

In the afternoon hours that day, we felt the sun and all of its offering: the faint warmth, the colour, the brightness and its inevitable descent into darkness. Stars so far above arced away into and across millennia far from us as we got the stove to softly caress the sound waves, that glowing hum with the quietest of crashes in the background, as small parcels of ice loosened and were pulled downward by gravity. The nourishment of hot liquid extended to our extremities, our headlamps casting beams at 3 a.m. Minutes later we stepped out of the 'ledge and positioned ourselves carefully. From here it was a day at the crag, we joked – Athol handed me the rack and then held my shoulder, an offering of everything we had done together. An empty sky, holding no wind, was ours to go into. And in that mysterious moment I looked upward into that world of shale and ice, and began climbing.

Much higher on the route, Athol organised the rack at my side then stepped left on steepening terrain, broken slips of shale shifting under his crampons. With care, his movements went up and left again, his head tipped back, his shoulders holding his pack carrying not more than water, some food, and a down jacket. His hands were opening and closing in a hopeless attempt to keep his blood moving. Soon the rope dragged heavily and we shifted the belay further left. And in the heart of all that shale we found a way, small deep breaks on the diagonal giving us a sense of flow. Then up and punching through jagged cuts of stone until suddenly there was a snow-covered ledge with room to breathe. It looked like one more short rock pitch above.

The sense of passing time had become a lost measure as we became disconnected from that logic, instead drawn into another dimension. We knew we were close. Athol moved off, scuttling into and up the fissure with an animal rawness, and I felt the heights we were in so immediately. Soon we were together again, and there was less around us – the steep snow shaped in wind-ripped ribbons and coarse runways going nowhere but downward. The snow was loose, granular, unstable. We could see to each side of us, as if trying to peer around a glass, or even around the curvature of the earth itself.

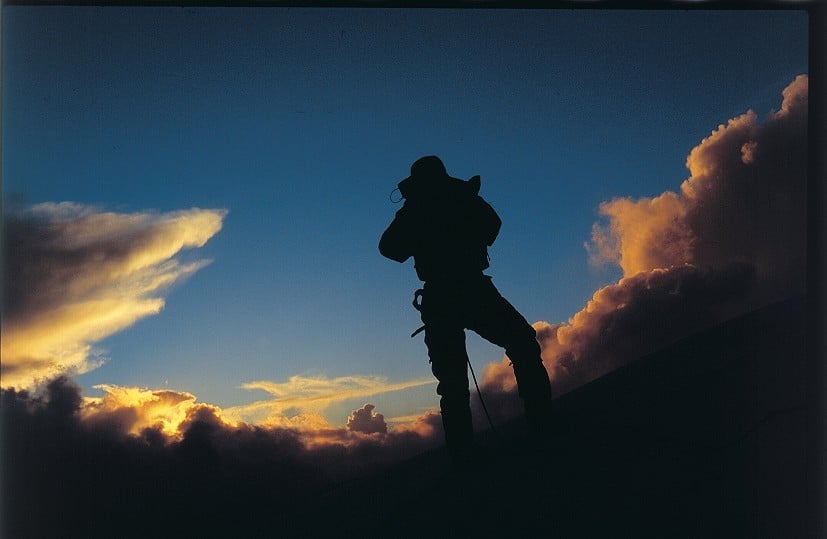

By this time, some clouds were rolling over themselves in silence nearby, almost as if we could touch them. Then pitches later in time the ground under our feet took a steep angle away and down and we both sat on the summit, exhausted and filled with the kind of warmth you know will soon leave you. We hurriedly put on our down jackets. I took some photos of Athol against the screaming sunset light, his image now a silhouette on film with eternity pushing out beyond him. The rope was looping and falling as we faced in and descended in the sort of rhythm that happens after many days and hours in this zone.

As the slope steepened we found the anchor we'd built on the way up. Rappelling, we tried not to bounce the rope. The darkness disguised the exposure we were caught up in. Then over the edge of the face proper, remembering the line and needing to get back slightly to the right as we dropped lower. Building anchors in the dark, panting as we pulled the rope and willing it not to get caught before it fell in space. Then eventually we were inside the 'ledge, scrambled up in exhaustion and pride, reliving the day we had just worked through, our voices filled with levity and enlightenment.

Hours later, snow was falling again and as daylight broke we were rappelling down the couloir with force and speed, not wanting to get caught if conditions worsened. One time after another we rigged and descended until we reached the bottom of the ice fields, the night sky occasionally revealing itself from higher above the cloud. The haul bag had the 'ledge and other non-essentials for that day inside, and so we cut it loose, watching it drift with gravity, scraping the face in glancing blows for fractions of seconds before going end over end until being lost from our sight. Then on the plateau we felt the joy of digging out the bags loaded with food and fuel and then cranking the XGK, the blue flame offering us so much. Our headlamps swept around as we gulped warm liquid and ate chocolate.

It was as if we were suspended in time and space, there on that plateau with all of the previous six days suddenly compressed into that moment. Athol stirred the bowl on the stove, the steam wandering upward out of the beams of light. We still had our harnesses on, our bare hands now accustomed to the cold, our gear strewn around with no need to be organised. And then in what became a starlit night, we kept looking back up to where we had been.

As we sat in base camp, the water of Kedar Tal was brushing against the rocky shore nearby. And as I felt nothing but the energy of Thalay Sagar, Athol's brother Tristram wandered over the moraine wall having hiked up from Gangotri. He slipped his pack off and in that laconic antipodean way said "That's a pretty nice walk up hey." Tristram, Athol, Patricia and another friend who had walked in, the late Erik Pootjes, and I all sat together amongst the glacial rocks with the natural ease that comes from being in the mountains. Some days later down in Gangotri, we camped on a terrace on the edge of the Bhagirathi river, the light from the sun breaking apart as it fell through the pine trees.

Since that time years have passed, years that are perhaps not even measurable on a geological scale. And yet in all that time "Thalay" has always been there, walking the hallways of my mind, an echo alive and resting at the same time, always adjacent to the reality of my daily experience.

When Athol died in 2012 it seemed so incongruous with the symbiotic relationship he shared with Nature, with being of it – its harshness, its indifference to anything but what it is, its requirement to live as it is: openly, honestly, and with full force. To scream at full throttle and moments later to retreat in shyness. To be there without motive, and then to explode in physicality and action. I say this of my friend because to me he and Thalay Sagar were, are, inseparable. And even in his death, on a rocky ridge in the Darran Mountains of his homeland New Zealand, he too was made in large part by our experience there and how it led him to what was next.

Philosophy says that free will is an illusion. But as climbers know, we stand a good chance of breaking that idea. That if ever we were to get the faintest glimpse of what the universe could or would be like if we were to subvert the path it put us on, we would find it climbing. In putting ourselves on the other side of consequence, in resolving ourselves to keep going upward knowing we may lose control at some point, but also leaning into the conviction of who we are and what we can do, we become unattached and beholden to nothing but what the mountain is, and therefore what we are.

And so if this were to be true, I think together we may have found the smallest fraction of that kind of glimpse as we descended into the darkness off the summit of Thalay Sagar. And with that observation I now remember Athol's hand holding that photograph of the north face beneath Bundaleer, and thus I remember all of him and what he represented, and how I miss that. "Imagine being up there Andy, above it all!" I now hear his voice in the dissipating evening heat of that warm day. The birds finding a bough to rest for the night, the dimming pale blue light in the skyward background, our conversation about everything that was possible, the mysterious dimensions of the Himalaya still unknown to us.

My sincere thanks to Tristram Whimp for Athol's photographs and to Charlie Creese for suggesting I write this reflection.

Comments