Jim Perrin pens a tribute to Joe Brown, who passed away on 15 April. An edited version of this obituary originally appeared in The Guardian.

Mountaineering has a levelling tendency. Self-promotion is met with mockery. Few of its would-be heroes escape reductive scrutiny. Accident and failure are often accorded greater respect than organisation or success. Yet even the devotees of the sport would accord heroic status to one figure above all others — Joe Brown, who has died aged 89.

The decade that followed his return from national service to Manchester in 1950 was perhaps the most crucial in the exploration of Britain's rock outcrops and mountain crags. Brown was involved in the Rock & Ice Climbing Club, founded in 1951 by a group of Manchester climbers, and developed a partnership with Don Whillans. This was to become the most significant in modern climbing history. As a team, they were formidable: the boldness and physical strength of the slightly younger Whillans balancing Brown's inspired improvisations and innate rock-sense.

The stages for the Rock & Ice advance were the Derbyshire outcrops and the range of cliffs along the north side of the Llanberis Pass in Snowdonia. On the August Bank Holiday in 1951, Brown joined forces with Whillans in an attempt on the right wall of Cenotaph Corner on Dinas Cromlech in the Llanberis Pass. Their first attempt ended in retreat as a cloudburst soaked the rock. A month later they were back, and this time succeeded on a route that was a psychological breakthrough in its acceptance of unremitting steepness and exposure, loose rock and poor protection. They called it Cemetery Gates, after a name Brown saw on the destination board of a bus as he returned through Chester that night.

That October, the same pair fought their way up Vember on Clogwyn Du'r Arddu — Brown's second attempt after a near disaster two years previously — and the Rock & Ice revolution was under way.

The activities of this group — and Brown in particular — expanded to include the French Alps, where British climbing had scarcely advanced for 50 years. On their first visit in 1953 the Brown-Whillans team made the third ascent in a very fast time of the recent Magnone route on the West Face of the Petit Dru — then deemed the hardest rock-climb in the Alps; they went on to climb an even harder line of their own on the West Face of the Aiguille de Blaitière that very soon gained and long retained a reputation for extreme difficulty.

As a result Brown was invited to join Charles Evans's reconnaissance expedition in 1955 to Kanchenjunga, the world's third highest peak, and its highest unclimbed one at that time. (Brown's acceptance, and apparent refusal to press for Whillans's inclusion – something he was in no position to do - was seen by the latter as a betrayal, and the two men, who had never been close friends, climbed less frequently together thereafter.) The climb was far harder, more arduous and committing than the 1953 ascent of Everest. Brown led the final difficult rock pitch to the top (minus four feet, as an undertaking had been given to the King of Nepal not to tread the actual summit of this holy mountain). His fame thereafter was assured. He followed up this success in 1956 with the first ascent of the Mustagh Tower, a 24,000-foot rock spire in the Karakoram that had rejoiced for over 60 years in the reputation of "Nature's last stronghold — the most inaccessible of all great peaks".

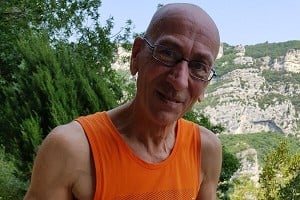

By 1956 Brown had established himself as the most considerable all-round mountaineer in the history of the sport in Britain. His first ascents on Pennine, Welsh, Cumbrian and Scottish rock had significantly advanced the concept of the climbable; in the Alps and the Himalayas his record was no less impressive. He continued to climb right through to his old age, and the list of his achievements grew longer with the years. His last recorded new climbs, on Welsh slate and in the Anti-Atlas of Morocco, were accomplished in his late seventies. But after those two great Himalayan ascents of the mid-1950s his climbing involvement was more relaxed. In that lies a key to his longevity in the sport.

He married in 1957. The horizons of his activity broadened. He began to be in demand for television work, where his flinty, humorous commentary, phlegmatic even when in extremis, acted as anchor to outside broadcasts from places as far apart as Iran's Valley of the Assassins, Welsh sea and mountain cliffs, Alpine aiguilles, Scottish sea-stacks and a wintry Ben Nevis. For one programme in the 1980s on the Old Man of Hoy he climbed with his younger daughter Zoë, whose character came over as amused and engaging as his own. He even made a quirky series of television shorts about fishing in inaccessible places, and acted as Jeremy Irons' double in the waterfall sequences of The Mission (the fact that Irons towered over him by almost a foot was concealed by careful camerawork). There was a measured wit and gravity and a light mocking touch about his screen persona that held true in all the relationships of his life.

He instructed for a time at White Hall Outdoor Pursuits Centre in Derbyshire, where he found time to master canoeing. He loved to fish quiet rivers, alone or with close friends. He had new phases of intense exploratory activity on British rock. In the early 1960s he combed the secretive valleys of southern Snowdonia for small, steep crags on which he sketched out the early masterpieces of climbing's modern age: Vector, Pellagra, Dwm, Hardd, Ferdinand. In 1965 he moved to Llanberis and opened the first of a small chain of outdoor-equipment retailers. He had significant climbing partnerships with men of younger generations. With Peter Crew he developed the awesome sea-cliffs of Gogarth and South Stack, producing an extraordinary series of routes: Mousetrap, Mammoth, Red Wall, Doppelganger, Wendigo. He continued to probe their intimacies to produce classic and teasing climbs long after Crew had failed to keep pace with his continued zeal. He made significant ascents of difficult peaks in the Andes. In the Himalayas he forged an alliance with Mo Anthoine and enjoyed trip after light-hearted trip — many of them unsuccessful in reaching their objectives, and that did not matter to him one iota — to difficult peaks in Garhwal and elsewhere. Even in his sixties he took part in an expedition dogged by bad weather to Everest's then unclimbed North-north-east Ridge.

Brown was born in Ardwick, Manchester, the seventh and last child of a poor Roman Catholic family. His father died when his youngest son was eight months old. Thereafter, his mother provided for the family through cleaning work and taking in laundry. He left school at 14 without qualifications to work for a jobbing builder. From Manchester the Pennine moors were no more than a bus-ride away: "By my 12th birthday I knew that going into the country was more satisfying to me than anything else," Brown wrote. At first it was child's play, then it gravitated to mine exploration in the abandoned copper workings at Alderley Edge and pot-holing in the White Peak. Inevitably, the progression was to climbing. For Brown this began among the arctic conditions of early 1947 in hobnailed boots at Kinder Downfall, above Hayfield in Derbyshire.

The rapidity with which Brown became perhaps the most significant figure in British climbing history was astounding. Within weeks this short, slight 16-year-old had begun to lead mountain rock-climbs at the highest contemporary standard. His native talent needed an educated and organisational ability to lead it on to fame and achievement. He found it through a chance meeting at Kinder Downfall in the spring of 1947 with Merrick "Slim" Sorrell.

Sorrell, three years older than Brown, was a pipe-fitter from Stockport whose solid and knowledgeable company underpinned the first phase of Brown's pioneering on rock. That their ability was notably higher than the prevailing standards of the day was established on a visit to North Wales. They had viewed the climb known as Lot's Groove on the cliffs of Glyder Fach — alleged to be one of the harder climbs in Wales. Two well-known climbers told them that it was only to be tried after an initial ascent on a top-rope and the consumption of a bar of chocolate: "Having no bar of chocolate we dispensed with a top-rope inspection and climbed the route on sight. We couldn't understand what all the fuss was about." On the same holiday Brown made an ascent of the Suicide Wall in Cwm Idwal — undoubtedly the hardest climb of its time in Britain. "I didn't find it too bad," he told me many years later. By the summer of 1948, having mastered the most difficult of the existing climbs, he began turning out his own repertoire.

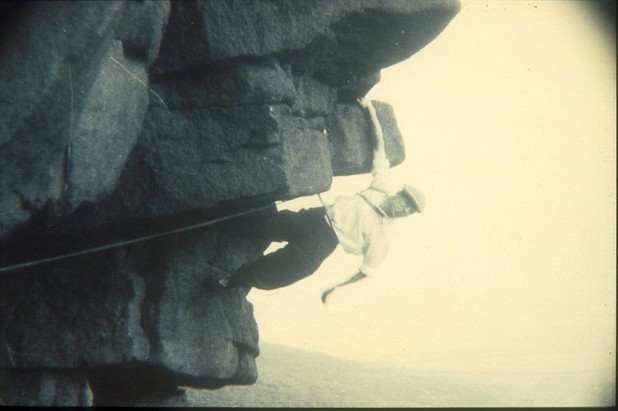

Initially these climbs were on Derbyshire and Yorkshire gritstone edges — brutally steep outcrops of abrasive rock in the ascent of which Brown displayed a suavely rhythmical and relaxed genius. His ability was now bolstered by being at the centre of a group of climbers from the Manchester and Derby areas, the Valkyrie Club. On crags like Stanage and Froggatt Edges, Wimberry Rocks and Dovestones, the routes that marked British rock-climbing's post-war revolution and were to bring it in line with pre-war continental standards were forged. Long-standing problems feared and revered by the sport's elders were vanquished beneath the insouciant plimsolls of a ragged and humorous 17-year-old youth. As a young climber myself in Manchester at the start of the 1960s, I was intensely aware of his presence and how much he had achieved by then.

With all the other greats of my time, I could understand how they climbed: fitness, physique, supple gymnasticism or sheer application. With Brown, there was something else at work. He was quite short, not heavily built, his muscles corded rather than developed, his movement smooth and deliberate. When I climbed with him, sometimes I would watch the way he made a move, copy it when I came to that point, and his way, that he had seen instantly, would be the least obvious and most immediately right. He was climbing's supreme craftsman, unerringly aware of the medium. That instinctual rock-sense never entirely left him. And with him too came a character generous, playful and straightforward. His mind may not have been academically trained, but he was sharp, informed, argumentative, and I think very wise. He loved the contest, be it physical or intellectual; he loved to wrestle. Once, after an exceptionally fissile first ascent on the Pembrokeshire sea-cliffs, he had led the marginally safer top pitch and I followed to find him sitting on the cliff-edge with nothing more than his feet down two rabbit holes for a belay, smiling dangerously. He pulled me to the ground and boxed me about the ears for risking his life and limb, scolding me for what he called the loosest route he had ever done. But he was laughing, laughing, and we ran back in perfect humour across the unmarked beach, the cliff crumbling slowly behind us in the western light, the waves rolling against it. He needed the simplicity of that conflict, and the character that emerged from it was perhaps the sweetest I ever knew, still generous and endearingly funny as he endured with dignity and humour the ill health of his final years.

(m. Valerie, 1957, who survives him, as do their two daughters, Helen and Zoe, and four grandchildren.)

Joe Brown, mountaineer, born 29 September 1930; died 15 April, 2020.

- CRAG NOTES: Mowing Word 21 Sep, 2020

Comments

He pulled me to the ground and boxed me about the ears for risking his life and limb, scolding me for what he called the loosest route he had ever done. But he was laughing, laughing, and we ran back in perfect humour across the unmarked beach, the cliff crumbling slowly behind us in the western light, the waves rolling against it. He needed the simplicity of that conflict, and the character that emerged from it was perhaps the sweetest I ever knew, still generous and endearingly funny as he endured with dignity and humour the ill health of his final years.

What a beautiful close. Thanks.

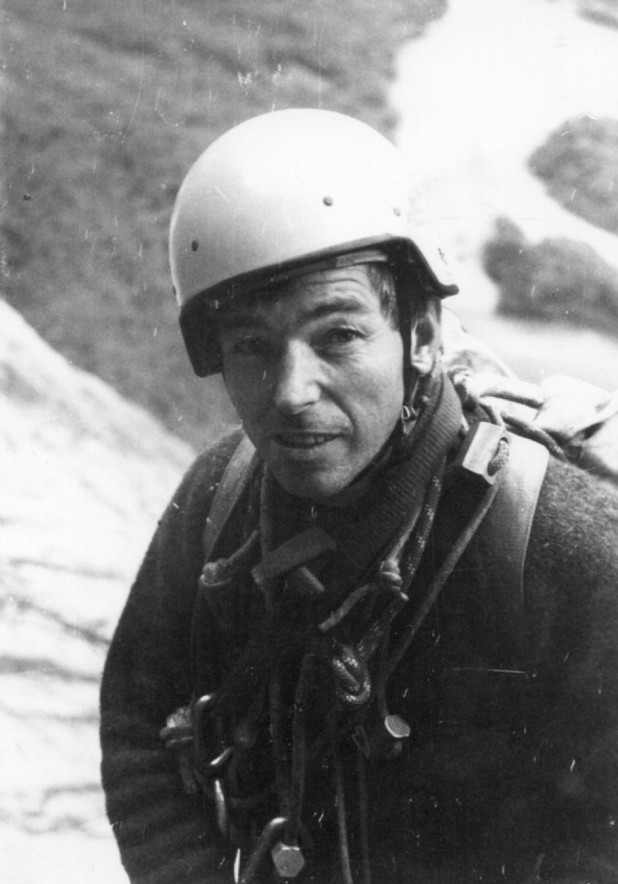

When I saw the accompanying b&w photo of Joe in his later years my first thought was 'what a fantastic statue'. It has a kind of great explorer feel, like the pre-First World War Antarctic giants such as Scott or Amundsen. If ever a climber deserved a statue then Joe would probably be prime candidate. But where (if anywhere) would be an appropriate site?

Near the lake / big car park below the Royal Vic, with Joe pointing at Cloggy, like the one of Saussure in Chamonix

Or by Chew Reservoir pointing up at Wimberry? Perhaps not .....

That's the best idea I've heard for the location, but can you imagine how Joe would have cringed at the concept?