We all realize we need new skills in order to improve. To climb the next grade, a more difficult mountain, or bigger wall requires us to learn. And we value learning, right? At times our actions and expectations, though, don't reflect this. Let's look at a few examples.

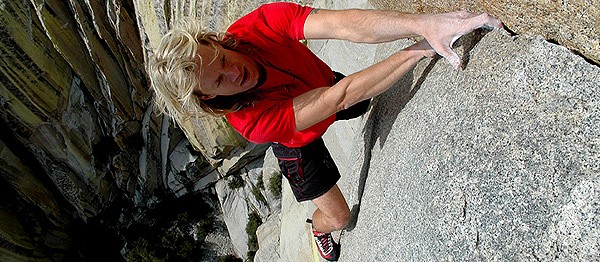

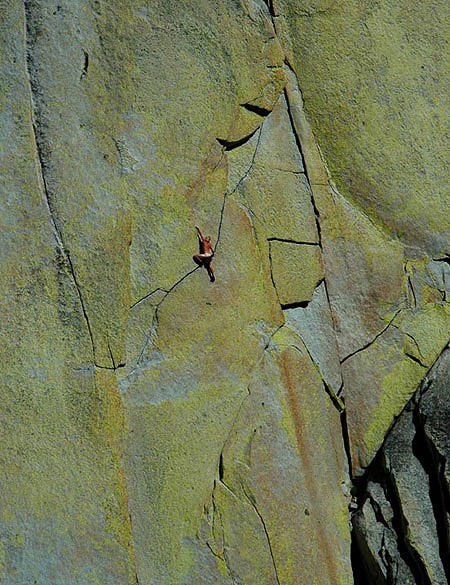

First, we limit learning by operating from past experience. Here our expectations are driven by what we know as normal and those expectations are superimposed on our present situation. In Rock and Ice (R&I) #142 Matt Samet writes about Michael Reardon's free soloing in “Meet Mr. Producer.” Reardon reported that he soloed 280 routes at Joshua Tree with several rated 5.12/5.13. After posting this on a climbing website, detractors quickly posted their doubts. What's interesting is not whether or not he did it, but the expectations people had about what was possible. 280 routes done in that style is quite a feat and not something that happens every day. So what seems normal and to be expected is very different than what Reardon accomplished.

Second, we destroy learning and motivation by creating expectations based on end-results. When we value the end-result, we are motivated by it. If we achieve the end-result, we stay motivated; if we don't, we lose motivation. Attention is focused on attaining the result instead of on learning what is required in the moment. Samet's article “You Wanna be a Climber, Son?!” (R&I #143) reflects this end-result expectation. Matt describes how parents have end-result driven expectations of their children and what they value. The persuasion to achieve the end results is exemplified in a real conversation that was overheard at a comp. Samet quotes:

Dad: If you win the comp, pizza party for you and your friends!

Billy: And if I lose?

Dad: We go home.

Billy: Waaaaaaaaaaa!

And after the comp

Dad: You did great in the comp, son!

Billy: Thanks, Dad...I really had a lot of fun.

Dad: But probably not as much fun as the guy who won.

Billy: Well, I've been training pretty hard. I kept climbing until I was totally pumped.

Dad: Was that before or after you fell off that problem all the other kids flashed in the qualifiers?

Billy: Umm...before.

Dad: Well, at least you had a good time, Billy!

Many of us have this type of expectation and are just unconscious of it. We value the result and create expectations based on that result. Our attention gets distracted from learning and what we need to do in the moment to climb well. We end up fearing we won't achieve it. And then, when we don't, we lose motivation.

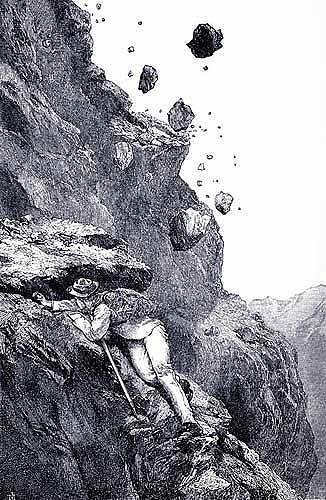

Finally, we create controversy and focus our energy on destroying people's reputation. This usually happens when we are jealous or envious of someone's accomplishment. The article on Michael Reardon introduced earlier is one possible example of this. Another example is described by Duane Raleigh in the Matterhorn article involving the Whymper team. On the descent, the seven members were roped together, Whymper in the back followed by the two guides (father and son named Taugwalder) and then four clients in the front. It was standard practice to have the most experienced climbers in the back to “belay” in case of a fall. As they crossed over the North Face one of the clients slipped causing a chain reaction. Whymper and the Taugwalders braced for the impact. Instead of pulling them off, the rope broke leaving Whymper and the guides alone and the four clients tumbling down the North Face. Whymper and the guides were suspected of fowl play and even accused of cutting the rope. The Taugwalders reputation as guides was destroyed. Mammut recently did tests on similar rope (half inch hemp) and concluded the rope probably couldn't have held such a force. All these years, attention was focused on creating controversy instead of being focused on learning what caused the accident or how it could have been avoided on future climbs.

Images © Mark Niles/Michael Reardon and Cannonade © Freda Raphael Historical Archive

Check out Mike Reardon's website the Free Soloist

Arno Ilgner is founder and president of Desiderata Institute, a multi-faceted medium which includes the Warrior's Way Course — designed to specifically help climbers overcome mental obstacles that are inhibiting their performance. Since 1973 Arno has developed and perfected specific physical and mental training methods, which are not only unique but highly effective as well. These methods are taught in the Warrior's Way Course. Through the Institute he also guides clients on mountains and cliffs in the Southeast USA. He served as a platoon leader in the US Army with tours of duty in Korea and Colorado has been a member of the American Alpine Club since 1983. He co-authored the first guide book to Fremont Canyon in Wyoming, and has published articles in Rock & Ice, Boulderdash! and Climbing magazines. Arno's interests range from mountaineering, to sport climbing, long free traditional routes, to big wall climbing.

His book The Rock Warrior's Way: Mental Training for Climbers is available from his websiteThe Warrior's Way and from Amazon

Comments