Angus Kille writes about his first route on El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. Alongside Dan McManus, Angus freed El Corazón 5.13b, making for a memorable first outing on the Big Stone...

"This is fixed isn't it?"

"What?"

"The static line…"

"No idea," said Dan, with almost imperceptible sarcasm. It was Dan's way of saying of that course the line is fixed, we're alone on the wall and we abseiled the same line to this ledge last night.

"Well I've got no idea either," I played along.

"I'd give it 50:50," Dan replied.

"I'll bet you then?" I said, fixing my ascenders to climb the rope.

"I'll bet you one Clif Bar."

"Deal." I said. "If I survive you're going to feel so stupid."

"I hope you die…" said Dan.

I kicked off the ledge and swung in a twenty-metre arc, giggling, with eight hundred metres of empty space hanging below my feet.

"It's so typical of you to survive," Dan laughed.

***

Our ascent began a week earlier, on a Sunday morning. I woke up with the nagging feeling that I was missing something, but everything was already packed. I would never really feel ready. We met in Camp 4, ready to get on the wall at first light, but by the time I was out of bed it was already light enough to see Dan without a head torch.

"Daylight savings," Dan remarked. "We're already an hour late." It wasn't the best start. By the time we reached the base of the wall we were fourth in line behind a few parties of aid climbers that must have set their clocks back.

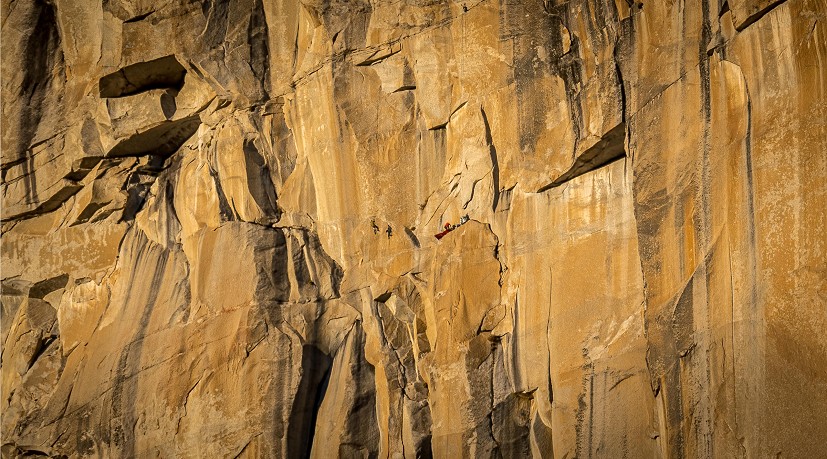

Our route was El Corazón. I knew very little about it actually; since this was Dan's eleventh route on El Cap, and my first, I had left everything in his hands. El Cap occupied the same space in my mind as it does in the mind of any climber: a suitably big area that my imagination struggled to navigate around. All climbing ideas were redirected here at some point, I couldn't live out my climbing career without visiting the 'Best Crag in the World'.

We paced around at the base of the wall. It was late morning by the time the party in front were clear of the first belay, so we dumped anything we didn't need and set off on pitch one of thirty-five. It felt like I had been waiting forever: more than summiting or climbing, I had anticipated those first steps onto the wall more than any others.

"I don't want you to find it too easy," Dan had said when we left the UK. "I hope you didn't train too hard."

Setting off I had the distinct impression that every move was an important step towards the summit; a mistake, even on easy ground, would cost us time and energy, which were limited by the food and water we hauled with us. I had weighed up this challenge for years, wondered if I could match myself to the feat of free climbing El Capitan, and with each move I was reassessing my chances.

El Corazón starts up Freeblast, a very well-travelled section of slabs whose thinner sections are notoriously slippy. After Dan had block-led the first few pitches he put me in the lead for the 'more interesting' pitches. For a while I stood on the 5.11b slab hopelessly looking for something to pull on before running out of ideas and committing my weight to smooth dimples in the rock. Padding incredulously up the slab, I felt that climbing El Cap would require a little more self-belief.

A few pitches later I wriggled through the Half Dollar chimney and emerged at the ledges of Mammoth Terraces. Since Mammoth has access from the ground by fixed ropes, we had hauled most of our kit there to save us hauling up Freeblast. It's a bit like cheating but it's standard practice. Dan led another couple of pitches into a broken corner system, by which time the sun had almost set, so we fixed our ropes and abseiled back to Mammoth for the night.

What happened next was by no means normal big wall antics. Four of our friends ascended the five or six fixed lines up to Mammoth Terraces to meet us on our first night. They even brought food. So we had Hazel, Maddy, Fatboy and Bunney over for dinner on our first night on El Capitan, with a full meal that Fatboy had cooked up in Camp 4 and cookies and beers that the girls brought.

We perched on the rocks around the terraces as food was doled out and beers were shared. It was surreal to have this monster challenge looming over us in the moonlight, steep and opaque against the stars, while around us headtorches lit friends' faces and camp bowls filled with curry, rice and a coriander tomato salad.

"Have you guys got enough water for this heat?" the girls asked.

"I think so," said Dan. "Unless the forecast turns out to be accurate, then we might be a bit thirsty.

When our friends disappeared down the ropes back to the valley floor, I couldn't imagine how we would miss their company and their food in days to come.

***

We started at 5 a.m. the following day. We each had a pint of black tea, cooked up some porridge and got food ready for the day: bagels, Clif Bars and an addictive mixture of salty nuts, sweet raisins and M&Ms we had appropriately named 'crack'.

Dan and I immediately ascended to our highpoint and started hauling the bags. It was as if our bags just didn't want to be hoisted up the wall; they would cling to anything, insisting on staying beneath this roof or around that corner as we dragged them up against their will. The summit suddenly seemed much further away. Two pitches and every combination of possible entanglement later, Dan and I were four pitches above Mammoth, at Gray Ledges, with the reluctant haul bags joining us shortly afterwards.

It was thirsty work. We were in the sun all day long and water was constantly on my mind. So far the climbing didn't come close to matching the difficulty of hauling the bags and going down to free them every time they were caught. Water is precious on the wall, but we had settled to take only the minimum, since it was by far the heaviest part of our load.

"It's only two litres a day we need each, I think." Dan had said. "Or maybe three, I'm not sure." I felt as though I could happily drink two litres sat there in the midday sun at Gray Ledges.

The next pitch was one of the hardest on the route, stretching thirty-five metres up a thin crack, out into the empty belly of El Cap. Impatient to make up for lost time, I tied-in and began taking falls on the lower boulder problem. I couldn't reach the crack without an awkward sideways jump that sent me swinging off as another layer of skin detached from my fingertips. For a few hours the whole wall came down to this small section of blank rock I was an inch or so too short to span. As a last-ditch effort, I hung from the holds I needed to catch and found one orientation in which my body could just about bridge the gap between holds at full stretch. Come morning, if I held this position just right, I could reach the crack and fight my way up the pitch.

We camped at the Gray Ledges that night. With a 5.13b redpoint for breakfast and a 5.13a to follow, it seemed unlikely we would make up the lost time. Having done this much climbing on any normal trip, I would probably take a rest day to recover and avoid injury, but instead I was tucked into my sleeping bag on this aluminium-canvas ledge with a bowlful of instant mash in my stomach ready to start Day Three in the morning. My knuckles creaked as I bent them around our little tube of lip-salve, complaining of the tight ropes and ascenders they had been gripping all day. My fingertips stung slightly as I balled up my down jacket into a make-shift pillow and stowed my headtorch alongside my toothbrush in a little bag clipped to the ledge. A tether ran from my harness, out of my sleeping bag to a bolt, keeping me attached to the wall along with the rest of our climbing kit, shoes, food and water.

***

We both led the pitch clean first go the following morning. I was stretched out at my limit, thinking tall thoughts to summon the reach I needed. When I had fought through another thirty metres of sustained climbing to the belay, I felt a lot closer to the summit. A slip or a fall would have cost us the entire morning, never mind the added wear and tear; we had just enough skill to escape a huge setback.

I hauled our kit, which was now just light enough that when inverted in my harness, facing the valley floor with my legs pushing upwards and my arms pulling downwards, I could haul our bags slowly up the face on a 1:1 pulley.

An unrelenting vertical layback pitch took us to a high and isolated position on the wall. We dug around for some lunch, excavating the tightly-packed haul bags carefully with our painful fingertips, eventually finding some of our pre-spread bagels. By this time the heat, the hauling and the climbing had had strange effects on our exhaustion. All it took was a peanut butter bagel to get stuck in Dan's dry mouth for me to slip into a delirious giggling fit. My sides were already burning, from the core workout and the bruises my harness gave me from hauling, but laughter was painful and infectious.

'5.12a loose, scary' was all the topo really told us about the next pitch - a huge traverse across the wall. I was to just wander across El Capitan until I found a belay, questing up and down, under or over towers and loose blocks, finding a line amongst all of the weird features where nobody goes. I had to pull some water and extra cams along on the tag line, the granite baked my hands and my feet were blistering but I eventually made it to the hidden belay somewhere fifty metres across El Cap.

Dan lowered the bags out for me to haul and I brought him over. I dug around thirstily in the haul bags, wincing at every item my fingers encountered. The water tasted sweet and invigorating, I could have drunk a gallon. Our skin, our mouths and our humour were drier than ever. I stuffed some salty-sweet crack in my mouth, unsure whether the mixture of raisins, salted peanuts and M&Ms was actually tasty or simply an addictive balance of bad flavours.

"This crack could be better couldn't it?" I commented.

"No. You can't improve on crack," said Dan flatly. "Unless you take the raisins and the peanuts out."

The sun set as I watched Dan take falls on the small wires he fiddled into the following pitch, eventually sketching through to a small ledge further left across the wall. We would camp there but I had no chance seconding in the dark, so when Dan was ready to haul I sat atop the bags and lowered myself out with them.

By now it was really night time and my headtorch was buried somewhere in the lower haul bag. I decided there was enough moonlight bouncing off the gates of my biners that I could do all of the ascending and rope work without it. By moonlight, the colour of the granite was flattened into monotone, leaving only texture: the micro features and the macro features, the large-scale rock architecture of one of the world's greatest rock walls. After a huge lower-out I ended up hanging in space below an unknown dihedral of granite five hundred metres up in the darkness.

The ledge was sweet. Just enough room for us to prop up the haul bags and set the portaledge up beside them. We even had a corner of ledge to shit on. What a luxury. We were on our own now, there was the odd headtorch at Mammoth way below, some at the base of the wall, but no voices. We were committed; below us the wall dropped away into the huge 'heart' feature of El Cap, making an abseil descent impossible and ascent through the corners above the only way out.

That evening, like every other, I tended to new cuts and scrapes, trying to keep the crumbled granite crystals, the dirt and general grime from inhabiting my broken skin. Scabs formed over old scabs, fingernails were broken or stuffed with dirt and chalk and my muscles complained of overuse.

"I'm going to give up climbing," Dan said.

"You always say that."

"I always mean it. I just never get round to it," he smiled.

You get to know your climbing partner pretty well on a wall. I would cook in one pot, eat from it, lick the spoon and hand it to Dan for his turn. There was no chance we would waste precious water on cleaning and any we used to cook with had to be consumed too. Morning tea always tasted of instant mash or noodles. There was little privacy for going to the toilet: half-hanging from a bolt with trousers pulled from under my harness and a polythene bag stretched over my arse, Dan would just try to ignore me at a metre's distance, despite my attempts at conversation. Needless to say, we each had an intimate understanding of how the other's digestive system was coping with wall food.

***

The following morning Dan made short work of the pitch we had left unfinished and I followed it clean. Once again we had just enough luck or competence to avoid taking a massive step back. We then dismantled the ledge and climbed another desperate slab pitch to reach the bottom of the huge corner system, which stretched six pitches up and ended in an impressive roof. The traverse of this roof was thought to be the hardest pitch on the route and it was usually what people talked about when we told them we were going to try El Corazón.

I set off up into the corners, finally escaping the sun. The first two pitches involved very three-dimensional climbing with huge flakes which would themselves be crags in the UK. The sense of isolation grew as we climbed deeper into the corner system, out of view of the rest of the wall. With my knees and ankles wedged in the cracks, spanning the corner and elbowing my way up, I reached a huge narrowing chimney that resembled the bottom half of an hourglass.

"You'll be fine," Dan told me. "It's just like the climbing wall back in Wales."

I was obviously nervous, knowing that I would have to wriggle up the chimney without gear until it was narrow enough for our biggest cam, at which point it constricted quickly to spit me out into an overhanging corner crack. I took my helmet off and climbed up to the bottleneck. There was nothing to hold on to, only the walls of the crack to press against, but my hands and feet slipped uselessly on the rock until I fell. Any amount of effort I could summon seemed futile. With a mixture of slipping, pulling on cams and swearing, I dogged my way to the top of the pitch, having lost the hope of climbing El Cap somewhere in the back of that crack.

Dan agreed that it was "kind of tricky" when he met me at the belay, but he hadn't struggled. I abseiled down the overhanging corner to work out what Dan had done with such ease and eventually managed a sort of struggled rhythm that resulted in upwards progress. I resolved to give it a good fight before the day was over, and climbed like someone with no reserve of power or skill, using every part of my body in every width of crack. I sent the pitch, but was forced to accept that The Captain would expect a little more humility from me; I wouldn't make it to the top without learning something.

From the west side of El Capitan you can only see a small part of the horizon clear of the valley's many buttresses. Throughout the day it's a small patch of blue sitting at the end of the valley, always at eye level. In the evening the sun sets exactly there, nestled perfectly at the valley's end, burning orange and then red and then going out completely. Hanging in space on our way down to the bags, I looked around at where we were, knowing that our huge corner system was just a small niche in the mountain; the largest chimneys and flakes had been almost imperceptible from the valley floor.

Dan gave me the 'air side' on the portaledge, which meant I could lie with the open air around me rather than being tucked against the wall. We hadn't predicted the weather being so stable and so far hadn't used the fly sheet we brought, opting instead to sleep under the stars with the occasional bat flickering overhead. The wall soaks up sun in the day and kicks out heat through the night like the biggest storage heater in North America. The moon would wake me up, drifting overhead in the night, the bright sky making a silhouette of the wall.

I didn't think I could really be more of a climber. I've built my lifestyle around climbing, made it my job and put it before everything else. Life challenges look like rock routes to me and I talk in climbing terms. But there I was, fully immersed, sleeping in my harness with the moon above me and fuck all below me.

***

Day 5 dawned with the usual grey light appearing in the sky, the various features of the valley coming into focus, fresh aches and pains joining the existing ones. I could feel my fingers stiffening in the night, my oversensitive fingertips twitching as they brushed the inside of my sleeping bag. Dust, dirt and dried blood would accumulate in all of the cracks and crevasses of my stiffened body. I felt hard and weathered, like the mountain itself.

After the usual pint of black tea, bowl of lumpy porridge and handful of crack, we dismantled the portaledge, whose aluminium limbs disassembled with a reluctant clanking I could relate to. We ascended our 60 metre fixed line and climbed the last two pitches of the corner system: chimney weirdness which squeezed and bit into the scabs on our elbows, knees and ankles.

When we reached the roof our bubble of isolation was broken. After two days alone on the wall we were surprised by two people abseiling in from above, whooping and howling with a staggering level of enthusiasm.

"Right ooooon Emily!! Ahwoooooouu!"

It was Thursday. Emily Harrington had told us she would be attempting to climb El Cap in a day today and this was her boyfriend and a cameraman, screaming encouragement and howling wolf noises.

"Ahwoooooouu!!"

"You guys look so rad right now!" They called over to us tucked in the corner under the roof. "Right on!!"

After days of only Dan's company, this was overwhelming.

I looked over at the roof pitch. It was stunning; a perfect roof capped the great corner system we had wriggled through, spread out to our left and tapered out about ten metres short of an ideal ledge waiting for us. I had been asking myself for days whether we would be capable of this pitch when the time came, or whether it would mark the end of our progress just as it neatly marks the end of those great corners.

I placed a cam from the belay and set off, traversing leftwards with my hands undercutting slopers at the back of the roof and smearing my feet on the wall. I threw my right foot into the corner of the roof, jamming it there to take some of my weight. Improbably, my foot locked in and I could traverse the roof shuffling along this way, carefully releasing and placing the heel-toe jam in an awkward, tense rhythm

It's one of the best pitches I've ever tried; it's impressive and improbable, scuttling along the underside of a roof almost at the top of El Cap, looking down at the valley 800 metres below. I had to rest on my gear to figure things out, but it came together beautifully. After a wild rock-over leaving the roof, the route offers you a crack to down-climb until you can make a committing step onto the side of the 'tower' that formed our bivi ledge. This was Tower to the People, our home until we could finish the wall.

I reached the ledge buzzing with excitement. The pitch was probably worth the five days of climbing it took to get there, just to feel that exposure, do those moves with my foot above my head and emerge onto a ledge overlooking the entire wall.

***

"When did you start?"

"3 a.m.," Emily said, smiling through her exhaustion.

"Twelve hours ago? It's taken us five days to get here…"

I was taken aback. Even more overwhelming perhaps was how crowded this small ledge was. I piled my rope and tag line carefully around my feet to try to make room for Emily and her small entourage. Emily's boyfriend Adrian, her cameraman and her partner for the attempt, Alex Honnold, squeezed onto the ledge beside me.

"So you're Angus?" said Alex. I hadn't met him before but we have mutual friends. "Tell me more about yourself man."

"Erm… well I'm not really that interesting to be honest," I confessed. What do you say to someone who's free-soloed the mountain you're making an expedition of?

"What do you think of El Cap?" asked Alex, feeding me some peanut butter pretzel pieces that stuck to my dry, cracked lips.

"It's a good crag. That pitch was a dream."

Dan came traversing under the long roof, at eye level for us at the ledge. Impressively, he almost climbed the pitch in one go, even when his worn hands slipped on the sloper underclings, he caught himself hanging by one foot for a moment. He eventually slipped at the end of the roof, making a good show for the spectators on the ledge beside me.

Dan joined me and we enjoyed chatting to the others, for the first time on the wall we could just sit and rest; it was too hot to free the roof pitch now and our hands were in a critical state, so we would have to wait until morning. I was impatient to keep going but Dan talked me around and had me haul our kit up to the ledge instead.

"Do you work out?" said Alex, commenting on my hauling. "You brought a man's man to do your hauling didn't you?" he said turning to Dan, the first and last time I will be described as a 'man's man'.

Emily continued her push to the summit, but after a kilometre's worth of climbing she fell, again and again at the final hurdle of the A5 Traverse. It was impressive and heartbreaking at the same time. She eventually conceded and ascended her fixed lines to the top, wishing us good luck as she waved goodbye.

"I'll return in a week or two!" she called down.

"We'll still be here," Dan replied, looking up from the portaledge.

The sun set in its corner of the sky while we lay there nursing our skin and our scabs. The valley was impressive as ever from here, the scale of it apparent now, in all of the empty space hanging beneath our feet. Down in the valley were middle class Americans driving by in RVs, pulling over to point at the wall and take pictures. They were an entire world away. Warm updrafts blew up the wall, giving us a sort of nostalgic taste of the valley, but occasionally bringing up what we had already spilt from the ledge.

"Oh Dan stop, stop!"

"I can't stop, I've started."

"Piss in a bottle or something, it's going on my face."

"It's too late now," he said. "Just embrace it."

***

The following morning I was tying in at the beginning of the roof pitch feeling sick with mild nerves and the strong taste of lip cream in my mouth. I fished out a bunch of M&Ms from our bag of crack to clear my palate.

"You can't do that! You can't just… you can't just take the M&Ms out!" Dan was outraged but I was giggling guiltily. "This is worse than the time I pissed on your face."

I folded into painful, silent laughter, my sides burning and my face contorted. Hanging there in my fit of delirious giggles I once again had the impression that my mind was failing in exhaustion before my body.

I gathered myself and set off on the pitch. Halfway along I noticed blood on my hands and found that a fingertip had torn open on the slopers. The wear was showing. I pushed on to the edge of the roof, pressing carefully with my feet to keep myself stable. I was suddenly in mid air, on the way to the valley floor before the rope came tight and I was swinging from some cams in the roof. I had been so close. I pulled up, finished the pitch and headed back to belay Dan.

Dan set off, shuffling along, squeezed under the roof with his right heel jammed awkwardly beneath it, the odd hand or a foot slipping but clinging on where any normal climber would have fallen. He made it cleanly to the ledge after some tense moments and impressive climbing. When he came back to the belay I couldn't completely share his relief. I knew that if I blew this attempt it would set us back some valuable hours and I would lose skin and energy I couldn't afford to lose. But I took a moment to breathe, set off into the traverse and relaxed into the jams and smears, letting my hips sink a bit to shuffle on through. At midway I stopped again to soak in the exposure below me for the last time before committing to the tricky step out from the roof.

I was through. Dan stripped the traverse as he seconded across and for a while we sat there enjoying the possibility that we might actually do this. The time we spent resting seemed to draw our exhaustion to the surface. The state of our hands, the pain in our bodies, the delirious giggles - everything seemed coloured with this pleasant tinge of exhaustion.

"I'm going to give up climbing," Dan said again, reclining on our portaledge in the sun.

We almost felt at home there. I had to watch myself for complacency, one missed clip and I would have thirteen terrifying seconds to consider my foolishness. We were never that far from the ground.

After a few hours of lounging we decided to move. We had two 5.13a pitches to go before easier ground, but we knew we wouldn't get that far in what we had left of the day, so we left the portaledge in place while we tried the pitches above.

I tied-in and inspected the holds leaving the ledge. They were thin, thinner than anything we'd pulled on so far, leading to a tight corner that ended in a roof. It was hard to convince my fingers that they needed to engage, bending over on micro edges, but I committed and scraped through to the endurance-layback style corner, which I stuffed a cam into and climbed hurriedly. I finished the pitch staggering through the wide roof section, my head spinning with a dizzying mix of surprise and exhaustion.

Dan followed up, equally surprised to climb the pitch clean. Next was the last 'hard pitch' of our entire route, the A5 Traverse, where Emily had failed. It was a well-bolted blank section of rock we would traverse rightwards to reach the relatively easy 5.11-5.12 ground beyond.

My body protested as I set off, the skin on my fingertips preciously thin, just like the holds on the wall and the rubber on my shoes. I fell, and fell again, swinging back to the last bolt, each time a little more exasperated with the heat, the pain and the difficulty. The repetition itself was exhausting: I was tired of being tired, we were so close now. I made it to the belay a few layers of skin later, brought Dan across and we bailed down to our ledge below to nurse our skin and consider our options.

"It's not worth going back up this evening," Dan said decisively. "Our skin won't be any thicker in an hour's time and we won't be any better rested."

We sat and chatted, tending to our various wounds. Our lips were dried and cracked but we were smiling anyway. I filed down some callouses and removed the ragged edges and dried blood from my cuts and grazes. I noticed my hands were shaking. Throughout each day we were subsisting only on crack and dry bagels, and energy bars when we remembered. I couldn't tell if we were losing our appetites because of our terrible selection of food or as an effect of the exhaustion, but at the time we needed it most, food was becoming less and less interesting. I wondered how long my body would take to recover from this.

***

By the time the sun was setting I was putting on my rock shoes one last time as Dan shook his head at me incredulously.

"I bet you send it now," he said.

"I'm just going to practise it…"

"It would be just like you to send it," he continued. "Last light, no skin on your fingers and your shoes almost worn through." I wouldn't send it, the pitch had felt too hard earlier, but I had to do something to put my mind at rest.

I couldn't really remember how to climb it, Dan had made it look much easier and I felt tired and clueless, climbing badly. My fingertips slid on the warm rock and the rounded tips of my shoes fell onto the thin edges as I scraped along the wall, but my toes eventually found the foot ledge below the belay and rocked-over onto it desperately.

Dan was chuckling, shaking his head. "Typical of you to send the bloody pitch."

The relief was incredible. I would be on the home straight in the morning and I could drag myself through that as long as I didn't fall to pieces. Dan was too tired to climb so he fixed a line from where he was and headed down to the ledge where we prepared our last dinner on the wall: instant mash and noodles.

It was probably only 8 p.m. when I turned my head torch off, pulled my sleeping bag over myself and nestled my head on my down-jacket pillow. I squeezed the carabiners loosely in my hand, checking that my makeshift pillow, my little bag of essentials and my harness were still tethered to the rock face.

I'm glad I chose a passion that I can be so immersed in. If Dan ever quit climbing, I don't know if he could inhabit another passion in the same way. For years, climbing has been my perspective on the world, my way of understanding things. But there on the wall, my metaphor for life grew life-size; instead of short ventures out of my comfort zone, I was living there for the week, or until the thing was done.

I rolled over. The pain in my body faded quickly into an exhausted sleep.

***

My fingers still creaked as I closed them around my ascenders on the fixed line the following morning. I kicked off the ledge and swung in a twenty-metre arc, giggling, with eight hundred metres of empty space hanging below my feet.

"It's so typical of you to survive," Dan laughed as I took the huge pendulum. It was Day 7. I won the bet and won a Clif Bar I had absolutely no need of.

As we reached the belay Hazel abseiled in out of nowhere, bouncing down from above. I had managed to get a message out to her saying we were topping-out that day, and she got up at 4 a.m. to hike up, get some photos and help us carry kit down. I don't know how we managed to swing that one.

Dan set off, anxious but climbing well, using his energy sparingly. There was now an extra pair of eyes and a camera lens watching us. Almost halfway along he fell and there was a tense frustration in his silence; we both knew the sun would come onto the face soon and each fall made each successive attempt less likely.

"I think this is one of those pitches that's easier if you're a really good climber," he said.

He went again, knowing the footholds and aiming for them, moving swiftly in sideways rock-overs to reach handholds which would skid out from under his fingers if he didn't have his timing right. By the time he stepped over to that final foothold I felt as if I had been holding my breath for minutes.

I nipped down to pack up the ledge and we hauled our kit for the first time in a couple of days. It was weird to see Hazel, a welcome outsider to our team. I began to feel an outside perspective on Dan and I as a climbing partnership, seeing how far we had come, our slick efficiency and weird humour.

There are two possible finishes to this part of the wall, and although our topo had 'scary' and 'not recommended' written next to the original finish, it was too impressive to turn down. A delicate layer of rock flared away from the wall forming these big handfuls of pancake-thin flakes that felt like they would cut our palms, or more likely our ropes. It was spectacular. More than a thousand metres of climbing culminating in this - big moves on bold features, moderate difficulty climbing in an anything-but-moderate position.

The final pitch didn't give anything away; subtle, balance-dependent moves led to a final jug to the top of the mountain. Hazel, as comfortable on the wall as if she'd spent the last week on it with us, helped haul our bags over the slabby slopes on top as I brought Dan up to meet us. We made it.

***

"It's not over until you're down and you've had a shower," Hazel said. We still had a long way to walk with a lot of kit on our backs, and until I had washed off all of the dirt, sweat and blood that my skin was stained with, it wouldn't be over.

We were a little embarrassed emptying our haul bags on the summit, sorting our disgusting waste and dirty kit in front of Hazel, we must have looked like feral boys. The smell of our shit in the poo tube, the cooking pot we hadn't quite licked clean and the clothes I had worn for the entire week (except my socks, which I changed once). Simply fitting all of our gear back into the haul bags was a challenge. I had an extra fondness for the familiar, well-travelled kit that had served its purpose getting us there.

By the time we made it to the valley floor we had a new assortment of aches to add to our already broken bodies. The walk down wasn't trivial, we were alarmingly top-heavy with our packs, even with Hazel carrying some of the load for us. Handling the packs whilst descending some of the steeper slabs and fixed ropes seemed to finish us off.

In the showers at Curry Village I cleaned all of the dirt from the corners and creases in my skin, my fingernails, my toes and my eyes. The dirt of The Captain washed off me, along with that burden of challenge, which had never allowed my attention to wander; I could look at our ascent as a fact now, not a possibility that wouldn't survive my indulging in it.

I bumped into Dan leaving the shower. "That's one of the best things I've done, you know," I told him. There wasn't much else to say, but he agreed silently.

It's worth doing a challenge that exposes you like that. The Captain saw me with my trousers down, it saw me falling, cut and bleeding. I was digging around for reserves of perseverance I had no use of in my comfort zone, some latent quantity that was otherwise redundant. This sort of challenge exposes that, and also hides the things that can only be important when you're not worried about water, like your email inbox or occasionally your ego.

There's a sort of excess of curiosity that climbers have, and climbing will always offer another frontier, another thing to discover, another way to satisfy that curiosity. There will always be another unknown that draws on some hidden capacity I didn't know about either. I'm glad there will always be more to climbing.

Comments

Brilliant writing!

Great piece, thanks for that.

This is one of the best things I've read on UKC for a long time.

Fabulous article. One of the best climbing pieces I've ever read. Bravo Angus.

Brilliant. Well done chaps. When I was younger I would have found that motivating/inspirational. These days I just think: rather you than me ;)

Cracking writing and clearly a fantastic effort on the route.