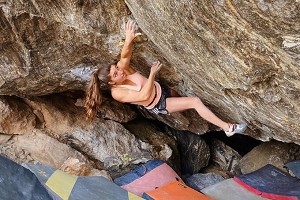

Mina Leslie-Wujastyk writes openly about her recent diagnosis of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) as a warning for other climbers who may not be eating enough to support their climbing...

Health and performance aren't always synonymous.

I am currently learning this the hard way and I decided to write about it in the hope of raising awareness and helping other people avoid the mistakes I've made. Part of me wanted to keep this private as it is fairly personal and there is also a certain level of shame and vulnerability associated with admitting to my errors.

I was recently diagnosed with Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) and the article below is a mixture of my story and more detailed information on the dangers of low energy availability in sport.

----------------------------------------------

If I were to have a climbing super power, it would be the ability to try really, really hard.

For as long as I can remember, digging deep has been my inner mantra; one more red-point, set or repetition regardless of how tired I felt. I always made sure to have that last go to check I was really "done", otherwise I would leave the crag with a sense of uncertainty and unease about whether my effort level was enough. My inner critic wouldn't be happy unless I was sure I'd emptied my tank and a day felt incomplete if I didn't walk out by head torch. I had also honed my ability for the "in-the-moment" try hard, the capacity to pull a performance from the depths of my being, out-performing my level due to pure tenacity.

Give me a training program and I'd always do extra. Multiple sessions a day, 5-6 days a week, running on my "rest" days. That's what "athletes" do right? Isn't that how we get better at climbing? Trying hard was invigorating and it was so ingrained in me to push to my limits that I think I lost sight of what exhaustion actually meant and felt like. Most days I would wake up tired, hit by a truck kind of tired, but after some coffee, yoga and inner chat I was ready to go again.

This mentality got me up some of my hardest routes and I have functioned in this way for a long time. Even so, I couldn't help but notice a mismatch in terms of input and output. I have struggled for a while to gain muscle mass and power through training but I thought it was just my genetics and so the solution was to work harder. Not that I really minded, I thrived on pushing hard; sitting precariously on what I thought was the edge of a fine balance. Over the last 6-7 years I naturally shifted more and more to an endurance focus. Not only did it suit me better, as power and basic strength became more elusive, but it also played to my love of resistance, battling and always eking out one more move.

The "less is more" approach makes objective sense to me; rest is an integral part of athletic progress and avoiding injury. There was definitely a discrepancy in what I knew to be sensible and what I did. I'm not stupid and there was a certain amount of cognitive dissonance at play but something always propelled me to do more and keep trying harder. Even when I broke my wrist earlier this year, I carried on going to gym a lot, finger-boarded with one arm and discovered greater enjoyment in running while I couldn't climb. All the while I knew deep down that I probably should have been resting more. Some of this issue was just love for climbing, running and any kind of exercise overtaking reason; but I realise now there was also an element of compulsive behaviour and using exercise as an emotional management tool.

On top of this somewhat ridiculous climbing and training work ethic I also haven't always had the most effective nutritional strategy. In 2019 I completed my first nutrition certification and it was through that objective study that I realised (with some degree of horror) my past errors. I spent years doing all sorts of things from low-fat or low-carb, high-fat diets to endless smoothie drinking to simple calorie restriction in order to achieve a lightness that was likely not what my genetic code had planned for me. At 170cm my weight has fluctuated from 56kg to 63kg; a constant inner conversation was at play. As I'm sure you can imagine, moves feel easier at 56kg than at 63kg.

Yes, I liked being lighter for climbing, but I wasn't ever noticeably underweight and I always thought I was supporting my body enough. My BMI never dropped below 19 (a BMI of 18.5-24.9kg/m2 is classified as normal range according to the 2014 NICE guidelines). This is perhaps just another example of why BMI is not a good measure of athlete health.

More recently, since studying nutrition, my fuelling became more effective but the load I placed on my body was still high and I'm aware of how inadequate my nutrition habits were for a long time. I realise now that in a chronic context my energy intake and timing just wasn't adequate considering the volume and intensity of effort I was asking from my body. Often I was eating what looked like a decent intake of nutritious food but, energy-wise, it wasn't compensating for the very high output.

Does any of this sound like you or someone you know? Bear in mind it's the mismatch between overall load on the system and food intake that is the poison here - you don't have to be climbing or training full time for this to be a difficult balance. If you have a family life, a physical or stressful job (and perhaps you commute on a bicycle) and then you add training or climbing on top you can easily find yourself in accidental under-fuelling territory. And, of course, there is the intentional under-fuelling in order to feel light that anyone is susceptible to.

Climbing is as much a culture as it is a sport and within that culture is a dangerous encouragement and acceptance of these kinds of excessive behaviours. Historically, there is a precedent for unhealthy and unsustainable approaches to training and nutrition that have helped to normalise some really dysfunctional habits. I didn't think I was crazy in what I was doing; I looked around and saw plenty of other climbers doing the same, and sometimes more extreme, things. Knowing what I know now, that scares me.

In September 2019 I was diagnosed with Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhoea (FHA) caused by Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S).

FHA occurs when the hypothalamus (the hormone control centre in the brain) is suppressed due to low energy availability and a cascade of associated hormonal dysfunctions then result in a lack of menstruation.

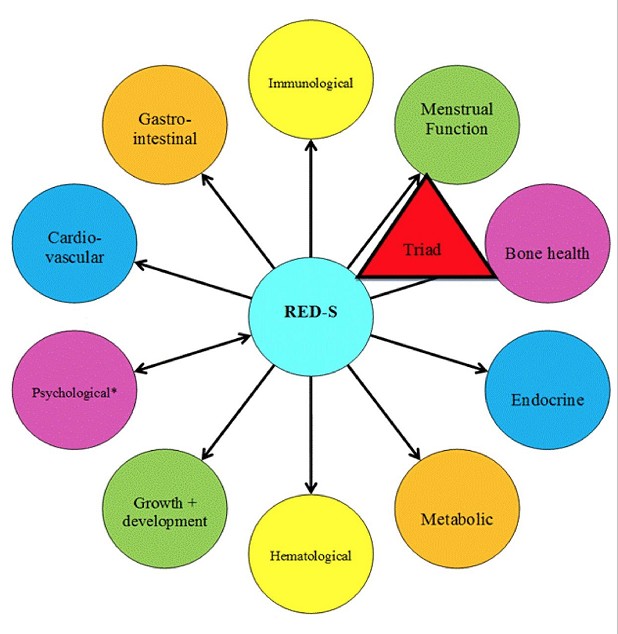

RED-S is the over-arching condition that describes the impaired physiological function caused by low energy availability, including but not limited to, FHA. You might be more familiar with the concept of The Female Athlete Triad which was updated in 2014 by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to RED-S in order to encompass the wider dysfunction associated with the condition as well as the inclusion of male athletes.

How did I find out? Reality hit home for me when, after many years on the contraceptive pill, I decided to come off it. To cut a long story short, my period didn't re-appear and after some investigation it became apparent that my hormonal profile looked like that of a post-menopausal woman.

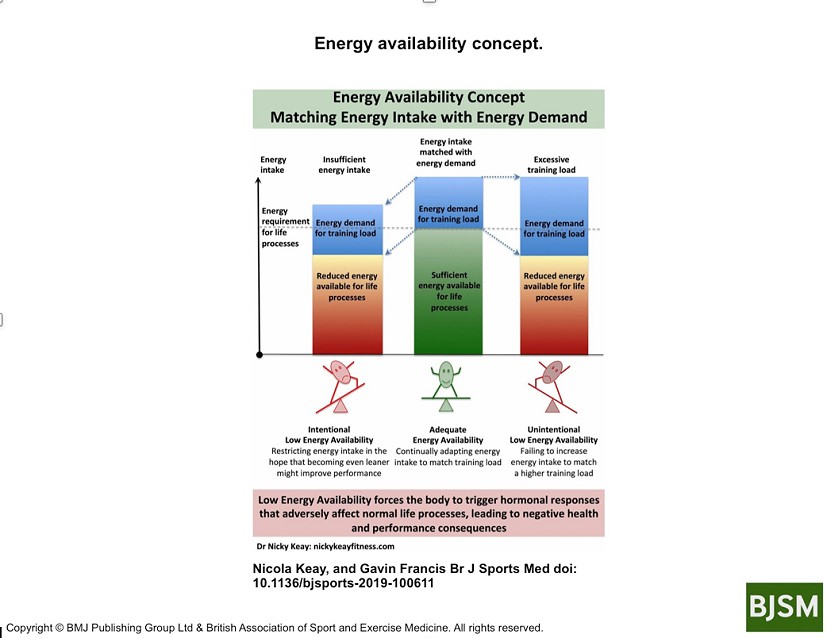

So, low energy availability is the villain here and lack of periods is just one of many problems associated with RED-S. Essentially, when the body doesn't receive enough energy (specifically carbohydrate) relative to demand, it will prioritise fuelling movement and down-regulate other physiological processes in order to conserve energy. Over-exercising, relative under-fuelling (intentional or unintentional), psychological stress or any combination of the three can lead to low energy availability.

RED-S can result in a multitude of dysfunctions with signs and symptoms including frequent illness and injury, lack of or irregular menstruation, fatigue, decreased performance and training response, impaired concentration, stress fractures, cold intolerance, mood swings, weight loss, delayed puberty and decreased morning erections in men.

One common misconception with RED-S is that being underweight or having a low BMI is a definitive pre-requisite for the condition. I thought that never being classed as underweight meant I was safe from this kind of thing, but the metabolic suppression (reduced resting metabolic rate) that comes with RED-S can lead to a slippery slope of consuming fewer and fewer calories to maintain a "healthy" weight while the in the background the body starts shutting down other basic functions. Ironically, long-term low energy availability actually produces adverse effects on body composition.

Each of us has a genetic set point weight range and too much variance from this is not physiologically ideal. As a result, you can have two athletes at the same weight and height where one will be healthy and the other could be in RED-S with negatively impacted physiology. It would be great if there was a clinical body weight "cut off" we could use to screen for RED-S but in reality it's just not that simple. There are, of course, instances of extremely low body weight where health will definitely be compromised but mostly we have to look at the bigger picture surrounding an athlete, their health and their behaviours.

So what are the risks associated with RED-S? Fertility is the one that jumps out to me: no ovulation and no period means a current state of infertility. Not the news I wanted at the age of 32, but thankfully it's reversible with the right approach. Threatened alongside fertility are bone, cardiovascular, psychological, metabolic and endocrine health as well as gastro-intestinal and immune function, growth and development and, of course, athletic performance.

Above: Health consequences of low energy availability (IOC Consensus Statement, 2014)

Bone health is worth talking about in more depth as chronically low levels of oestrogen from RED-S can negatively affect bone mineral density (BMD) causing early-onset osteopenia and/or osteoporosis. This is no joke; osteoporosis is a serious and debilitating condition that is difficult to come back from. Damage done now can lead to unrecoverable losses in BMD which can leave a person open to stress fractures with minimal or no trauma.

Due to my extremely low oestrogen levels and the large time frame over which my clinician suspects I have been in RED-S, I was sent for a DXA scan to evaluate my bone density. I was very lucky to have maintained a healthy BMD most likely due to favourable genetics and the multidirectional weight bearing characteristics of climbing. This was a massive relief for me but it isn't the same for everyone - I am well aware that I got off lightly.

OK, time to talk about the pill. While taking the pill has no direct causal link to creating this condition, it does mask the most obvious symptom in women. I was on the progesterone only mini-pill on which I didn't menstruate, from the age of 19. This is a common, medically approved, side effect of this kind of pill. It's worth mentioning that the bleed experienced in the 7-day break from a combined pill is NOT a natural period and therefore not evidence of a well-functioning reproductive system.

So, I haven't had a period in over ten years due to the pill. Had I not been on hormonal birth control, somewhere in that time, due to my behaviours (over-exercising and relative under-fuelling) my period would have stopped. It probably would have happened gradually;, initially my cycles might have become longer and my bleed lighter before they eventually ground to a halt. In this parallel existence, free of exogenous hormones, I would have had a massive warning sign that something wasn't right.

In reality, I effectively had a blindfold on. I put the lack of strength gains down to genetics, the tiredness down to training hard, the bad memory and concentration down to my head injury and just thought it was funny that I got so cold at night that I needed a sleeping bag in spring (in the house, also under a duvet...).

Don't get me wrong; I am not completely anti the pill. It signified a huge step forward for the sexual freedom of women by providing control over fertility and it helps many women with the debilitating symptoms that can come with menstruation. However, in the context of an athlete who pushes their body very hard, a regular natural period is a useful indicator of health.

You might wonder why am I talking about all of this. It's pretty personal and on some levels I would rather not share it but I am painfully aware that this is a conversation that needs to be started in climbing. If talking openly about this stuff helps one person to see the signs in themselves, their friend, their student or child and prevents someone else ending up in the mess I'm now in then it's totally worth it.

I had to go outside of the climbing community to find more information and to find athletes talking about their experiences. It's common in dancing, cycling and running; I suspect it's very common in climbing too.

Hard climbing and training for climbing has really taken off and our community is achieving great things due to increased knowledge and dedication to improvement. Psyche is high, and that's great, but we need to be mindful of the pitfalls of over-training, pushing too hard and not eating enough. It is very possible to neglect health in the pursuit of performance, intentionally or unintentionally, and this risk is especially high in weight sensitive sports where, alongside high energy output, "lightness" may be considered optimal. Nutrition is a key component to achieving and maintaining good performance, but it can be very easily neglected and/or manipulated negatively.

So, where to go from here?

Recovery, for me, involves a personal paradigm shift towards prioritising health. This means that, for an undetermined length of time, climbing performance will have to take a firm back seat. That doesn't mean I can't or won't be able to climb (and climb well) but only in the context of eating more, resting more and honouring tiredness. I need to gradually untangle myself from habits and attitudes that don't nurture and support my body and to re-invent some aspects of my relationship with climbing. I've got to re-direct my try hard towards compassion, health and nourishment. In the short term I may feel uncomfortable in my body as it undoubtedly changes during the process of recovery and I must accept that it may not reflect the image I hold as "athletic" and have previously strived for. I imagine that, short-term, my performance will suffer. In the long term, as my physiology recovers and my hormones restore, I hope to be healthier, stronger and more robust both physically and mentally.

RED-S can be obvious but it isn't always. People can be winning races and sending climbs in a state of RED-S. In those cases it might take longer to discover and the effects can be very serious and far-reaching.

If you think you or someone you know may be going down this road, please seek help from a professional. One thing I have learnt from this whole debacle is that, despite having a high level of knowledge and understanding, it is extremely difficult to be objective about yourself and your own behaviours. The first step is going to your GP for further investigation and to rule out any other medical conditions associated with your symptoms. There are also clinicians like Renee McGregor (Sports Dietician) and Dr Nicola Keay (Sports Medicine Endocrinologist) who specialise in the treatment of RED-S through their clinic EN: SPIRE as well as a new London-based NHS clinic dedicated to RED-S than can be accessed via your GP.

In a broader sense, before any physical detriment or diagnosis may be apparent, please consider whether under-fuelling may be an issue for you. I would urge you to look seriously at your habits around exercise and food and to take a long-term view on health. The feeling of climbing well is amazing, I'll be the first to say that, but it's not worth losing your health over and it's totally achievable in a more sustainable way.

For more in-depth information on RED-S please see the links below:

British Association Sport and Exercise Medicine

EN: SPIRE clinic run by Dr Nicky Keay and Renee McGregor

IOC RED-S Consensus Statement 2014

IOC Authors' 2015 notes on Consensus Statement

IOC 2018 RED-S Consensus Statement Update

Endocrine Dysfunction in RED-S

Hypothalamic Amenorrhea and the Long-Term Health Consequences (paper)

Comments

Good article, honest, useful, thanks

This is made more powerful by being written by a role model at the top of the sport too. Anything to keep the alarm bell ringing re eating disorders and over-training is great, thank you.

Fab article. Thanks.

I'll be honest - initially I thought 'another indulgent article about a female athlete who wants to 'climb hard' and has an eating disorder.

But very very good. Very well written, thought out and explained. Overtraining/under eating is a common problem in other sports, particularly those with a focus on endurance (it is rife in the amateur triathlon world), and a greater awareness of it in climbing is only a good thing. As discussed it can have longer term effects on the body than just a short term slump in energy levels.

One emphasis I would change though is that it can effect men equally as women, it is definitely not a 'female problem', despite in the case of females the main symptom being masked by period issues.

Props Mina for going public on this and with such frankness.

RE below quote and by extension presumably currently popular low carb / ketogenic type diets presents extra specific risks?

“Essentially, when the body doesn't receive enough energy (specifically carbohydrate) relative to demand, it will prioritise fuelling movement and down-regulate other physiological processes in order to conserve energy.”