Last month, Robbie Phillips, Will Birkett, and skipper Scott Johnston set off in search of The Thumb, a route that Robbie first came across in a book.

However, this was no normal guidebook.

It was a book written more than three hundred years ago, recounting the story of a journey to the archipelago of St Kilda, and featuring the description of a sequence of climbing so extreme that it sounded almost beyond belief.

Intrigued by the history of St Kilda, the centrality of climbing to the St Kildan's way of life, and the question of whether the climbing could truly be as extreme as it was claimed to be, Robbie gathered his crew and set off.

We got in touch with Robbie to find out more about the adventures that followed:

Your St Kilda adventure drew attention to the relationship between climbing and history, how did you first come across The Thumb and the adventures of the local St Kildans on it, and what was it about the story that piqued your interest?

I read a book called 'A Late Voyage to St Kilda', which was written in 1698 by the Gaelic speaker Martin Martin, and was about the original St Kildans and their way of life.

In it there is a section dedicated to their climbing activities used for fowling (catching birds and their eggs) in which he describes the St Kildans climbing their most challenging climb, a route up a sea stack between the isle of Hirta and Soay. He wrote how they named the route 'The Thumb' because, and I quote:

'that of all the parts of a man's body, the thumb only can lay hold on it…during which time his feet have no support, nor any part of his body touch the stone, except the thumb, at which minute he must jump by the help of his thumb'.

This excerpt from the book captured my imagination - the idea that there were Scottish islanders performing impressive acts of technical climbing well before the Victorian era, an age when most climbing historians tend to agree that the contemporary idea of technical climbing began.

The St Kildans climbed without any gear, only a horse-hair rope tied around their waist used to anchor at the top for the other climbers to follow, or to pull them back into the boat if they fell and landed in the bubbling froth and choppy swell of the Atlantic.

I really wanted to understand what the St Kildans did, if the story about 'The Thumb' was true, or if it was just dramatised by Martin Martin, and I thought a journey to St Kilda to find 'The Thumb' would be a wonderful adventure.

Tell us about the journey to The Thumb - how long does it take, and what's it like being that far away from the mainland on a small boat?

Sailing to St Kilda is not an easy journey – it takes a day to sail to the Outer Hebrides and another day to get to St Kilda, and the seas are rarely calm.

I get terribly seasick and I will admit, I'm somewhat useless for most of the journey as a result. Even when you arrive in St Kilda there is very little protection from the sea, only a small bay on Hirta that protects you a bit, but not always!

I don't mind being away from the mainland, but I do find being restricted to the boat with the incessant bobbing and swaying a little hard to manage at times – and when you do finally lay your feet on solid unmoving ground, it feels fantastic!

St Kilda itself is quite a small grouping of islands and probably only takes a couple of hours to circumnavigate them. This years objectives were to find and climb 'The Thumb', but also to make the First Ascent of the incredible, unclimbed, and enormously overhanging 200m sea cliff on the Western most tip of Soay – without a doubt, the most remote sea cliff in the British isles!

How did you got about planning this adventure, and recruiting people for it?

I had already been to St Kilda in 2022 with a great team of friends, Will Birkett, Guy Robertson, and Hamish Frost, not to mention our skipper Charles Smallwood – the full film of this trip is on my YouTube channel. That year we climbed the NW Face of Soay via a new line we called 'The Last Queen of Scotland' (E5) and on the eastern island of Dûn with 'The Lost Boys' (E5).

For the 2023 trip the rest of the team had other plans, but I am very good at convincing Will Birkett to join me on mad adventures. Will is one of my favourite people to climb with as we always have a good laugh, he's usually psyched on the dirtier bolder pitches that I don't like, and it takes a lot to break his spirit… I think I almost pushed him over the edge on this trip, but still not quite… I must try harder next time!

Between our two objectives (The Thumb + The Huge Unclimbed Seacliff) they were only within an hour sailing of each other, but both require an exceptional skipper who can not only sail safely between the two, but also judge swell/tide/weather/wind/etc… and be able to get us close enough to the rocks to 'safely' jump onto them in order to climb.

I was lucky enough to find Scott Johnston (@Yachting_Scotland + @the_kilted_sailor) who was simultaneously an incredible skipper, but also about as mad for adventure as we were, and willing to push it to the line (and often a bit further) in the name of adventure!

Because we'd been in 2022, we knew what to expect from the climbing and adventure side of things, but probably the most important thing we did was liaise closely with the NTS (National Trust for Scotland).

St Kilda is a dual-status UNESCO World Heritage Site and boasts a stunning amount of natural and cultural significance, both of which the NTS works tirelessly to conserve and sustain, as well as managing sustainable access.

It's so important as climbers that we don't disturb or cause damage to the areas we visit, which is why I'm incredibly grateful for the guidance and support from the NTS. The work they do is invaluable to conserving such amazing places and heritage in Scotland.

Tell us about the climbing itself!

SOAY – The 200m Wall

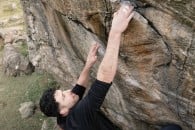

The first climb we did was the enormous sea cliff on Soay – like most other things on St Kilda, I think it's probably a type of Gabbro, but nothing like Skye! It's much smoother in texture and forms in quite rounded features, from big cracks to enormous globular flakes. We climbed 'sea up', and after pitch one I knew it was the most committing climb I'd ever undertaken, as it was so steep I had no idea how we'd get back down if we didn't succeed!

I had spent a whole year analysing a high-resolution image of this wall, but I had made one major mistake… the size of the features were so much bigger in reality, and blank sections between cracks weren't so much a body length, but more the size of a car!

Pitch two was brutally hard. After falling several times, I finally managed to break through and reach a hanging belay. Pitch three was even harder, I suspect around E7/8 (fr8a+) climbing with a really bouldery crux - the sun was beating down hard on us and I'd run it out to a black totem that was only biting on one lobe!

I took one fall, and the piece ripped.

By now time wasn't on our side, and falling here was wasting time, so I gingerly sat on the piece, heart in mouth, and stood up on a sling to reach a better cam, succumbing to the will of my head over my heart and accepting that one point of aid will just have to do.

The climbing then eased in technical difficulty, but the rock quality drastically worsened as I battled up enormous fissures that exfoliated flakes of rubble into your eyes and mouth… I shouted to Will 'Watch me here man, I'm about to pull on a…' CRACK!!!

I came hurtling towards him slamming directly into his head! The other hold had broken, but within minutes I was back on the sharp end. Will confessed the day after that his head hurt for the rest of the climb, but he never said a thing… Cumbrian lads are hard as nails, especially the Birketts! Finally the end of the pitch was in sight as I grunted through a barrelling roof onto a vegetated slab to a thank god belay!

Two pitches remained, one incredible E5/6 head wall and a final ramp that walked us onto the summit – in the final metres of the E5/6 I found myself singing a silly little song to myself, delirious of where I was, what we'd achieved, and that we were not dead!

Will and I hugged on top as only climbing partners who've really been to the edge and back do – I have found these are the experiences that build bonds for life, and it's really cool that we have this one to look back on for many years to come.

The Thumb

Climbing 'The Thumb' was more of a climb through history – jumping from the dinghy onto the sea stack, suddenly I felt the enormous weight of time, thinking to myself that possibly the last person to stand where I am now was 100-odd years ago and would be on a fowling mission to catch food for their community.

We didn't know 100% for sure where the line was, but it became pretty obvious when you looked at Stac Biorach and could see where the birds nest during the nesting season – the copiously thick layers of guano are a dead giveaway.

The line would obviously traverse up to that, so we started to climb – me, Will, and our skipper Scott!

I figured the climbing couldn't be that hard if the St Kildans did it barefoot and essentially solo, but I was surprised to find a slightly overhung section, poor feet, sloping handholds, and then a tricky rockover/mantle during which you loose your handholds and kind of 'thumb sprag' the roof a bit!

That was it… I realised in that moment that this was probably what Martin Martin saw back in the 1600's… he hadn't climbed 'The Thumb' himself, but he'd watched from the boat, and with a non-climbers perspective I am positive he saw this very technical climbing move and described it as thus:

'that of all the parts of a man's body, the thumb only can lay hold on it…during which time his feet have no support, nor any part of his body touch the stone, except the thumb, at which minute he must jump by the help of his thumb'.

The ledge you rock over onto is so small, that you have to tentatively change your body position into a sort of crawl, losing all use for your feet as they dangle over the edge, reach out across a gaping rocky crevasse onto a protruding 'thumb-like' feature, and then up the Guano covered ramp to the nests.

There is a lot of room for creative license here by Martin Martin, but this section was genuinely challenging, it required me to manoeuvre my body in such a way that I have learned to do so intuitively from fifteen years of climbing, but to Scott, this was near his limit! With no good gear until the belay above where Will sat waiting, Scott was risking a huge pendulum, and I stood there coaching his every hand and foot placement. When we arrived at the belay I swapped leads and did the next much easier pitch, and then Will took us to the summit.

Standing on top I surveyed the summit, looking for some hint of the St Kildans having been there, but the light was dying quick and I saw nothing but a few bird carcasses. Unbelievably I forgot to take a team summit selfie, but after Scott and Will descended I took a moment to think about where I was, and imagined some St Kildan from hundreds of years ago standing here, barefooted, laden with dead birds, and probably feeling pretty chuffed with himself for climbing up the whole stack!

There is good evidence that they didn't just climb for survival, but it was a part of their very being – they climbed from early childhood, their feet developed an almost prehensile appearance from decades of barefooted climbing (not too far off what my feet look like from stuffing them in climbing shoes), during the offseason they would climb the stonework of their houses to keep fit, and achieving feats such as 'The Thumb' gave them status amongst their peers, and a bounty of extra birds from that seasons catch for their family. I might not climb for survival, but I live to climb, and I felt in that moment connected to them.

'The Thumb' we estimated to be within the realms of Severe (S) to Hard Severe (HS) and has limited protection, so you definitely need to be a confident leader and second to guarantee not having an epic!

Some of your most audacious and explorative climbing has been done just a (figurative) stone's throw from home. Tell us about your love for exploring Scotland - is it something that has developed naturally, or did you make a conscious decision to start trying to seek out adventures that are on your doorstep?

When I was younger I would always look abroad, motivated more so by what I thought looked awesome in pictures/film/social media. However over the last ten years or so, climbing in Scotland has become an ever increasing motivation for me to the point that when I do go abroad, I am often thinking about home.

I guess there is an element of home pride in being Scottish – many of my English/Welsh/Irish friends don't see what I see, and claim that North Wales, the Lakes, or places abroad are better. They might be right, but for me Scotland just has something that I can't let go of…

There's a sense of mysticism to the landscape, and the romanticism that I see echoes in the music, art, and culture of Scotland. When I go climbing in Scotland, I really feel a deep sense of connection that I don't get anywhere else, and it empowers me in a way that I don't have any delusion I should be elsewhere. I feel my best self when I am in the Highlands or islands swinging about on a project, often on my own or with my dog, Bonnie.

I would say that now all my biggest projects are in Scotland, the things I am most excited about in climbing are in Scotland, and anything I do abroad is just training for Scotland.

How do you go about finding these new objectives?

I go for lots of walks! I am not really a hill walker kinda guy, but I have kind of become one as I have developed this intense fascination with the Scottish landscape and the idea that my next big climb is just hiding behind the next hill, or hidden in a glen somewhere.

As for the island stuff, having a sailboat helps a lot. I've been very lucky to make friends with several folk with boats who are super keen to explore the Scottish islands and coastline, and I think if I can make it work, I'll probably always try and do a sailing trip each year.

Is the next adventure already lined up, or are you looking for inspiration?

I have a lot of projects back home that I can't wait to jump on, but for now I am in Catalunya sport climbing, trying to get fit ahead of the Spring and editing the film of this latest St Kilda trip for YouTube and film festivals next year.

- REVIEW: Montane Men's Resolve XT Jacket 20 May

- INTERVIEW: Aidan Roberts on climbing Arrival of the Birds and Spots of Time 16 May

- ARTICLE: Resistance Climbing - Existence is Resistance 15 May

- ARTICLE: Who would have won Tokyo 2020 under the Paris 2024 scoring system? 27 Apr

- INTERVIEW: Jack Palmieri on climbing 200 8s in a year 15 Mar

- FEATURE: Kendal 2023 - E12? There and back again with James Pearson 2 Nov, 2023

- FEATURE: BMC Launches Crowdfunding Campaign to Secure Sirhowy Crag for Climbing Community 24 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Freja Shannon talks Risk, Craic, and Brit Rock 4 Oct, 2023

- ARTICLE: Kendal 2023: The Future of Hard Bouldering - Will Bosi, Jerry Moffatt, Shauna Coxsey 25 Sep, 2023

- VIDEO: Ryuichi Murai's First Ascent of Nexus, 8C+ 5 Jun, 2023

Comments

What a cool quest, I love this adventures. And I agree with him, nothing beats Scotland

What an amazing read and even more amazing story!