In this three-part series, Pete Reynolds AKA 'The Lakeland Rock Doctor' takes us on a tour of the varied and interesting rocks of the British Isles upon which we love (or occasionally hate) to climb...

Part 3: Metamorphic Rocks

Metamorphic rocks - the rocks of change, are messengers from deep inside the Earth's crust; they preserve information on the heat and pressures found beneath our feet. They are perhaps the most colourful and exotic type of rock with a dazzling array of names, nicknames and pseudonyms. Think schist, greenstone, quartzite, pelite and psammite – though not all are gneiss to climb on*.

What the names mean is not the issue for a climber; the important thing to get your head round is - what did the rock start off as? If it was a sediment, you're likely to end up with something layered and sometimes shiny (for instance slate or schist). If it was an igneous rock, you're likely to end up on something very hard and crystalline (such as gneiss or greenstone). Both types climb completely differently; some can be almost granite-like to climb on (gneiss), while others can be very similar to sandstone (e.g. quartzite – a sandstone that has had a very gentle baking). But if I had to pick one word to summarise climbing on metamorphic rocks, I'd probably go for…fear. This is dished out by the rack full at our best-loved (?) metamorphic venues of Dinorwig and Gogarth.

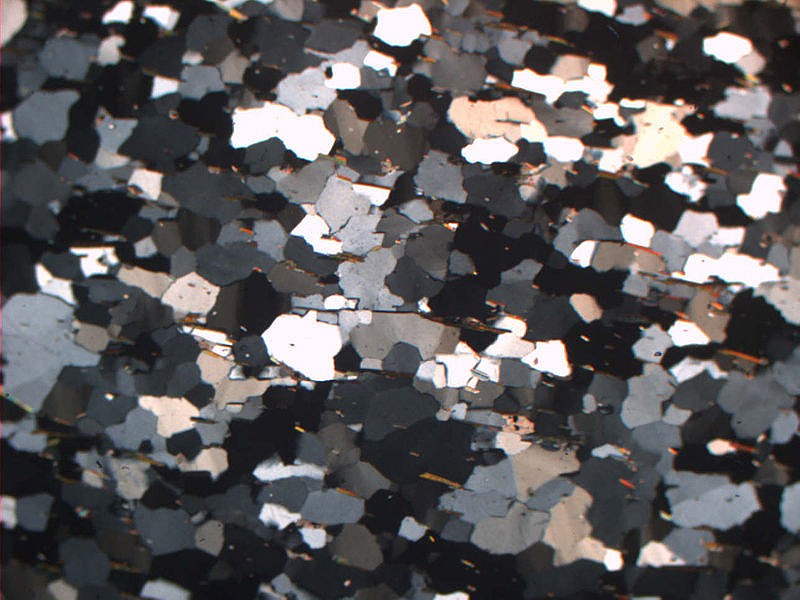

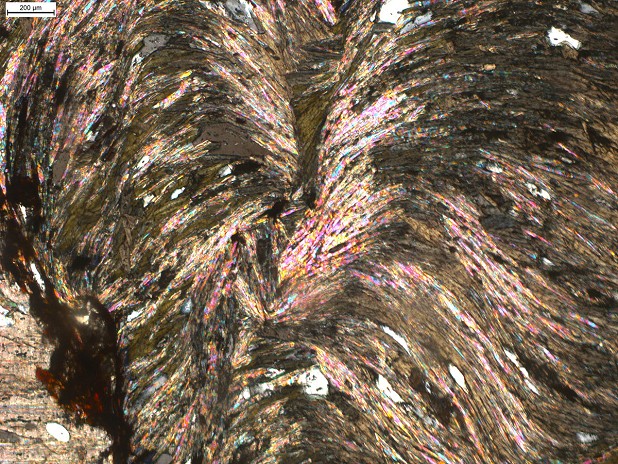

(The schist above has been sliced thinly and placed under a microscope. "Polarized" (or filtered) light is then shone through. Note how you can see that the plate-shaped minerals are all aligned.)

Dinorwig slate quarry in North Wales, along with the other slate quarries, are venues like no other. They have corners, slabs and dihedrals to puzzle and perplex the climber. Add to this a combination of creative holds including razor-sharp crimps, shot holes, quarried edges and decrepit metal work, and you have a recipe for adventure. Slate began its life at the bottom of the ocean as a pile of mud. Given heat from the Earth's interior, as well compression, all the minerals in the mud began to form new, larger minerals. These minerals are much like playing cards in shape, and with a bit of a squeeze, line up in a stack (think of a deck of cards).

Slate slabs are notoriously frictionless and there are no protruding crystals to stand on. This results from the stacking of these flat minerals. If you look at slate end on, you can easily see the structure – especially on crimps on a slab. The layering of minerals means that water can't easily penetrate into the rock, and slate doesn't have pore spaces like sandstone does. So in the absence of crack systems (formed by weathering or quarrying) slate dries quickly. However, whilst it might dry quickly, slate is also known to fracture easily in one orientation – it's easy to split a pack of cards, right? This is why slate is used for roofing tiles; the planes between minerals crack and separate easily. So be careful with your nut placements!

The second metamorphic monster is also found in Wales. Gogarth, the quartzite beast, is composed of what were originally sedimentary rocks, deposited in deep seas. The sediments were deposited at a crucial point in Earth's history – the Cambrian period. Back then, 540 million years ago, there was a major explosion in the diversity of animal life, as well as the "evolutionary first" of the formation of animals with a hard shell. Trilobites are probably the most famous incarnation of this period, but are no more glamorous than a woodlouse. Don't go looking for trilobites at Gogarth though, focus on whether that jug you're holding is going to snap off, or whether your gear will hold a fall.

This is because the rock quality at Gogarth is notoriously variable, often within a single route. The solid sections of rock form as a result of the dissolving of quartz grains at depths in the crust, forming a quartz crystal slurry. When the slurry recrystallizes, it essentially glues all the grains in place. Remember how we talked about the type of sediment being deposited changing over time (see the second article)? Well that accounts for the layers of varying rock. Some layers of rock are particularly rich in clays and carbonate, meaning that the cement has been less well formed, making the rock friable. The sub-vertical bands on Mousetrap are the most obvious manifestation of the varying rock layers; these have been tilted by the movement of tectonic plates. Prepare accordingly; in the words of Libby Peter, take a Yosemite rack to Gogarth and climb with care.

Gogarth and Dinorwig both escaped from the Earth's mantle. Not all metamorphic rocks are this lucky. The rest are committed to a molten grave, from which they emerge as igneous rocks. And so we see that all rock types are engaged in this slow recycling from sedimentary, to metamorphic and igneous. Our opportunity to climb them represents an infinitesimally small fraction of their transient existence. Understanding this process is not really "necessary" for a climber. Knowing your schists from your sandstones won't make you climb any harder. Similarly, stargazing will not make you more productive at work. But understanding a little about how rocks form, how they change, and how they got there can help us appreciate the overwhelming scale and time on which the Earth operates. A little knowledge, like music, can enrich a journey.

*Bad puns are a geologist's hallmark

Comments

Great article. I learned something!!

Thanks!

The Geologists are Coming: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1NU51lJIdrg

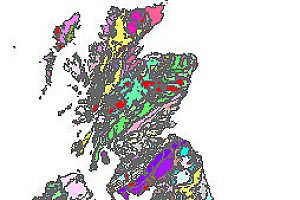

Interesting but all the examples are Welsh - lots of metamorphic rock of many types in Scotland